30 September 2023 | Healthcare

Dollars and Doctors: The Double-Edged Sword of Corporate Healthcare

By workweek

Once upon a time—way before my time, but perhaps in your time—physicians used to make home visits. If they couldn’t see you in your home, you’d go to their private practice, where you knew the entire staff well, and they knew you.

Since that time, medical care has become extraordinarily corporatized. Payers, major retailers, and private equity have invested billions of dollars into medical care through acquisitions of physician groups and medical startups.

In this article, I’ll highlight the state of corporate American healthcare, discuss how we got here, and tell you why corporatization of healthcare is a double-edge sword.

Dr. Optum, Dr. CVS, and Dr. Private Equity

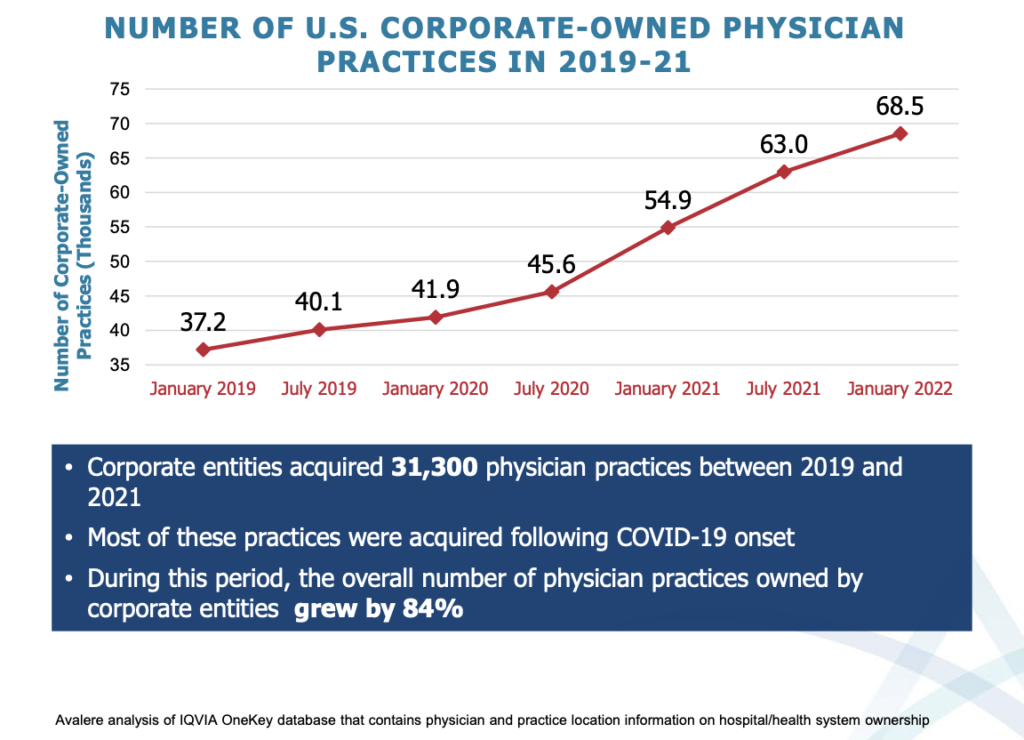

The pandemic catalyzed the corporation of American healthcare. There was an 86% increase in medical practice acquisition by corporate entities from 2019 to 2021, with corporations now owning nearly 30% of physician practices. That equates to 68,500 practices.

At a more granular level, one in five physicians find themselves employed by a corporation, totaling 143,000 physicians. Before the pandemic, only 92,400 physicians were employed by a corporation.

To explain what’s happening, I need to bucket “corporations” into three different segments: insurers, retailers, and private equity.

Insurers

UnitedHealth Group’s Optum has 70,000 salaried or affiliated physicians, making them the largest physician employer. This is 7% of all active physicians! Other health insurers are following UnitedHealth Group’s playbook by become a payvider through acquiring physician groups.

Retailers

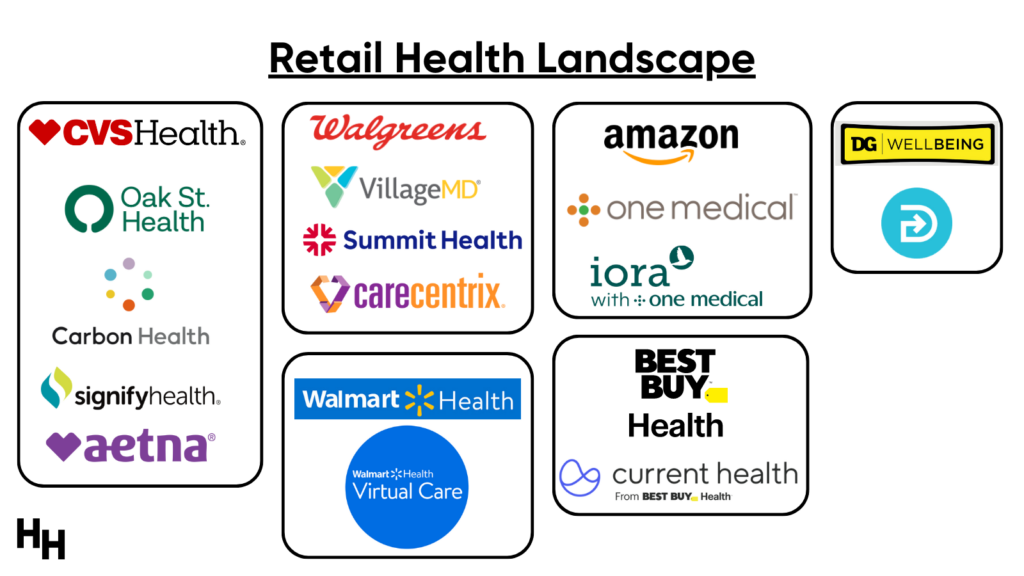

Major players in the retail health space are CVS Health, Amazon, Walgreens, Walmart, Dollar General, and Best Buy, several of which retailers have reportedly committed $50 billion into primary care, equivalent to $50,000 per patient.

Within the last two years, we’ve seen retailers make significant moves in the healthcare space:

- CVS Health acquired home health company Signify Health for $8 billion, gaining access to 10,000+ clinicians. In addition, they also invested $100 million in a partnership with primary care platform Carbon Health and acquired primary care platform Oak Street Health for $10 billion.

- Walgreens’s VillageMD acquired Summit Health for around $9 billion, adding 2,000 primary care physicians.

- Amazon acquired primary care company One Medical for around $4 billion, gaining access to 8,000 clinicians.

So, it’s clear that major retail companies are swiftly infiltrating the healthcare sector, leveraging billions to broaden their healthcare offerings.

Private Equity

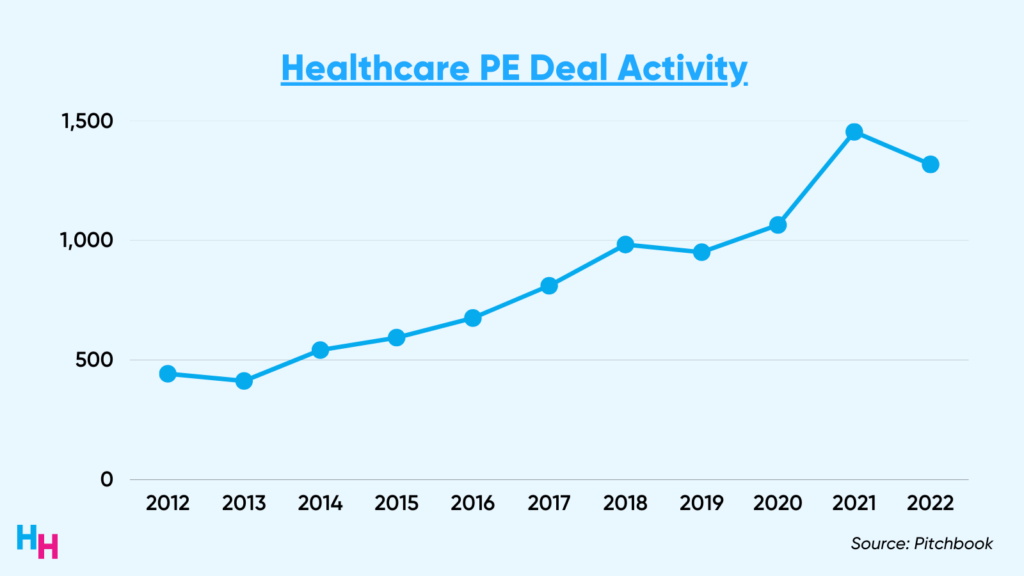

Healthcare services private equity deals grew an estimated 200% between 2012 to 2022. “Services” include primary care and multi-specialty groups, skilled care and behavioral health, and practice management companies. However, some PE-backed provider firms are running into financial trouble. Check out Blake’s dive into the fall of PE-backed Envision Healthcare.

“Separation of Church and State”

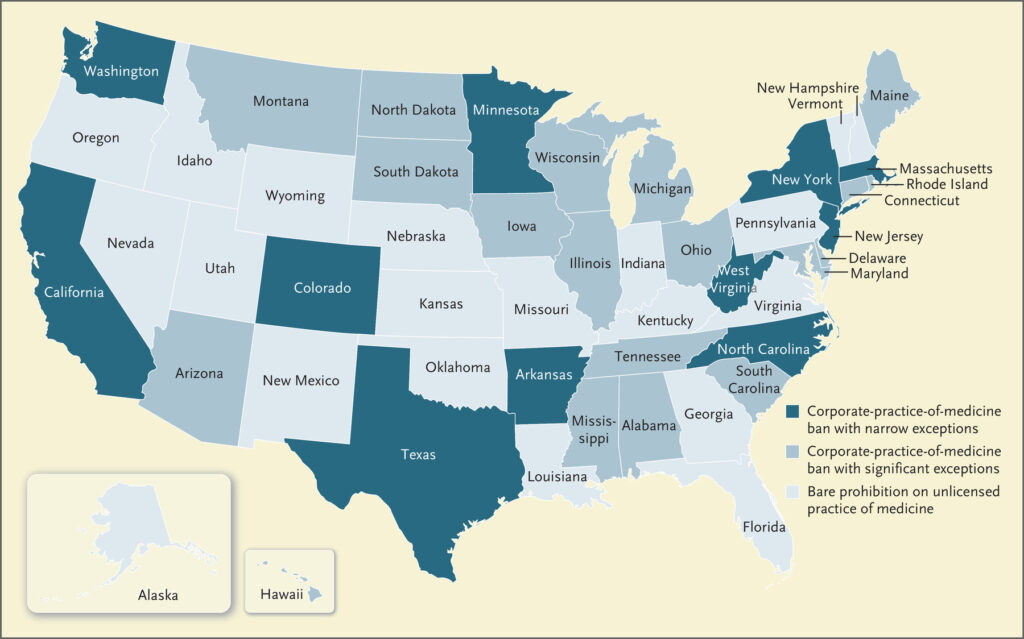

The healthcare equivalent of “Separation of Church and State” is the corporate practice of medicine doctrine, which (should) prohibit non-licensed physicians from owning or controlling medical practices. These frameworks were designed to maintain the independence and integrity of two fundamentally different areas of society or professional practice.

Corporate practice of medicine laws vary state to state. Some states have strict corporate practice of medicine laws, prohibiting non-physician-owned corporations from owning/employing medical practices, while others have “wave the hand” laws, prohibiting just the unlicensed practice of medicine.

Corporate practice of medicine laws haven’t quite worked, which should be obvious since I’m writing about the corporatization of American healthcare. Corporations (private equity, especially) have strategically found ways around the laws using two popular models:

- The management service organization (MSO) model

- The “Friendly PC” Model

In the MSO model, the MSO (AKA the corporation, private equity firm) contracts with a physician group to provide various management, administrative, and support services. However, the physician group retains ownership of the medical practice and has “complete autonomy” over clinical decisions and patient care. The MSO typically receives compensation for its services, which can be structured in several ways such as a percentage of the practice’s revenues, a flat fee, or a per-member-per-month fee.

In the “Friendly PC Model,” a “friendly” physician is made owner of the MSO, giving the MSO “de facto ownership and control of physician practices.” The MSO typically provides operational support but owns the real estate and equipment. The contract often grants the MSO extensive management rights and responsibilities over the non-clinical aspects of the practice and includes tight noncompete and NDAs. In case you’re wondering, Oak Street Health and One Medical use this model (and they were acquired by CVS Health and Amazon).

Dash’s Dissection

The corporatization of American healthcare is a boon and a bane.

Boon

Billions of dollars of corporate investment into medical care should spur innovation. Physician groups and medical care startups now have access to capital they previously never had or would ever have. One Medical, for example, was worth $4 billion when Amazon acquired it. Amazon’s market cap is $1.3 trillion, 325x the value of the One Medical acquisition. This capital can be invested into health tech to improve operations and patient care, which is highly needed.

Additionally, these physician group or medical care startups acquisitions’ may also relieve physicians and providers of management responsibilities, allowing them to focus on delivering high-value care to patients. These firms can improve administrative efficiency and revenue cycles, and aid in implementing quality metrics required by CMS, for example. And recall from my previous article, these retailers and PE firms are moving fast into the Medicare Advantage space because of the reimbursement.

Lastly, corporations may serve as a lifeline for medical groups or medical care startups that struggle to compete with large health systems or locally consolidated medical practices. Or, PE firms may give an end-of-career physician who built their own practice a comfortable exit.

Bane

The idea of profit-motivated corporations involving themselves directly in medical care seems formidable and, to some extent, paradoxical. While the influx of capital they bring can unquestionably catalyze innovation, efficiency, and advancements in healthcare services, it also raises profound ethical and practical questions about the motivations behind healthcare provision.

Profit and medical care don’t mix too well—it’s fraught with potential conflicts of interest. The fundamental objective of medical care is to prioritize patient well-being and health outcomes, a goal that may not always align with corporate ambitions of revenue maximization and cost minimization.

In fact, the focus on profits seemingly negates the need to ensure patients receive high-value care: care that is high quality and cost-effective. There is evidence showing patients cared for by PE-owned dialysis centers in concentrated markets have higher hospitalizations, lower survival rates, and decreases in staffing compared to non-PE-owned dialysis centers. Additionally, evidence shows gastroenterologists significantly alter care processes, such as in using anesthesia with deep sedation during colonoscopy, after they vertically integrate (with PE firm, for example). Patients’ post-procedure complications increase substantially.

Lastly, it’s well established that PE-owned hospitals add more profitable service lines and discontinue less profitable ones. These hospitals also have fewer full-time employees, lower patient satisfaction scores, and poorer quality metrics compared to non-PE-owned hospitals.

How major payviders and retailers play out in regards to value of care they produce is TBD. We know their services can drive revenue, but can they also improve patient outcomes?

In summary, the corporatization of American healthcare is experiencing a pivotal transformation, with insurers, retailers, and private equity firms making extensive acquisitions. While promising innovation and efficiencies, this change raises serious ethical and practical concerns, primarily due to the inherent clash between profit pursuits and commitment to patient well-being. The central challenge remains in balancing revenue-generation aspirations with the enhancement of patient outcomes and the delivery of high-quality, value-based care.

Stay ahead in healthcare with my weekly Healthcare Huddle newsletter, covering digital health, policy, and business trends for 30,000+ professionals. Share with colleagues and subscribe here.