16 September 2023 | Healthcare

Medicare Advantage: The Golden Goose with Hidden Costs?

By workweek

There’s a lot to love about Medicare Advantage if you’re a beneficiary, plan issuer, or corporation in the MA market. Beneficiaries get some extra benefits like dental coverage while insurers and corporations reap massive revenues from MA payments.

Despite its stellar enrollment growth, MA—capturing 51% of the entire Medicare population—is fundamentally broken and costing the government (us taxpayers!) an unfathomable amount of money.

In this article, I’ll highlight the MA money machine, dive into its reimbursement flaws, and discuss how it’s causing the corporatization of American healthcare.

The Money Machine

The MA space is lucrative, if a health insurer or corporation plays the game right. Below, I explain how MA plans are reimbursed. See if you can find areas to maximize reimbursement.

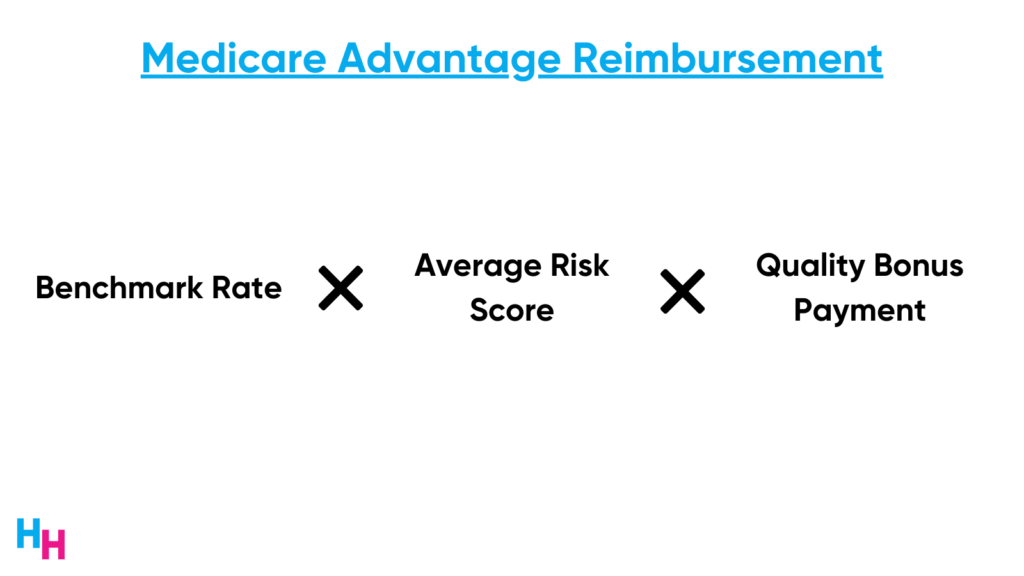

First, CMS provides MA plans with monthly capitated payments, irrespective of beneficiaries’ subsequent healthcare usage. This capitation approach encourages MA plans to prioritize high-value care, thereby anchoring MA in a value-based care reimbursement model. Here’s how the capitated rates are set:

- Benchmark rate: this is the maximum amount CMS will pay an MA plan for an average beneficiary in a certain community. The benchmark is based on a five-year rolling average of traditional Medicare fee-for-service payments in said county. Pay attention to this.

- Bidding Process: Every year, MA plans submit bids to CMS, which represent their own estimated costs of providing care for an average beneficiary in a certain community. If a plan bids below the benchmark (that is, their care costs are less than CMS’s benchmark), CMS will pay the plan its bid plus a percentage of the difference between the benchmark and the bid. If a plan bids above the benchmark, enrollees will need to pay higher premiums to pay the difference between the bid and the benchmark.

- Risk adjustment: Once basic payment to the MA plan is settled (based on the benchmark and bid), CMS will adjust the payment based on the health risk profile of each individual beneficiary in a certain community. CMS uses the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) system to adjust for risk. Each HCC represents a category of related medical conditions. These conditions are hierarchically ranked, meaning some conditions are considered more severe than others, and therefore more costly. MA plans receive higher reimbursements for managing these complex conditions. Pay attention to this.

- Star Ratings and Quality Bonuses: CMS assesses the quality of MA plans using a Star Rating system. Plans that achieve high scores get a nice (understatement) bonus payment from CMS. CMS paid nearly $13 billion in bonus payments to plans last year…

Did you identify the areas to maximize reimbursement?

Flaws in MA’s Reimbursement Model

Risk adjustments and benchmark rates are two “problematic” areas of CMS’s MA reimbursement model.

Risk Adjustments

Basic payments to MA plans are adjusted based on the health risk profile of each beneficiary. The sicker the patient, the more the MA plan will be reimbursed due to greater risk adjustments. Or, the MA plan can encourage its physicians and providers to upcode or intensify coding.

- Upcoding: assigning higher diagnostic codes for patients than what is medically necessary or accurate, which inflates risk scores for beneficiaries, and thus leads to higher reimbursement.

- Intensify coding: coding for all possible diagnostic codes a patient has, increasing the number of HCCs, and thus increasing reimbursement.

The HCC system (described above) is inherently flawed because complex conditions were underreported when designing the system. CMS used traditional Medicare fee-for-service data to determine how much to reimburse for the complexity of certain conditions. Due to underreporting, certain complex conditions (e.g. type 2 diabetes with peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy) seem to occur less frequently than they actually do, and therefore are reimbursed at higher amounts.

Knowing the above, MA plans can take advantage of this and intensify their coding to capture “rare” conditions, increasing their reimbursement, even if accurate.

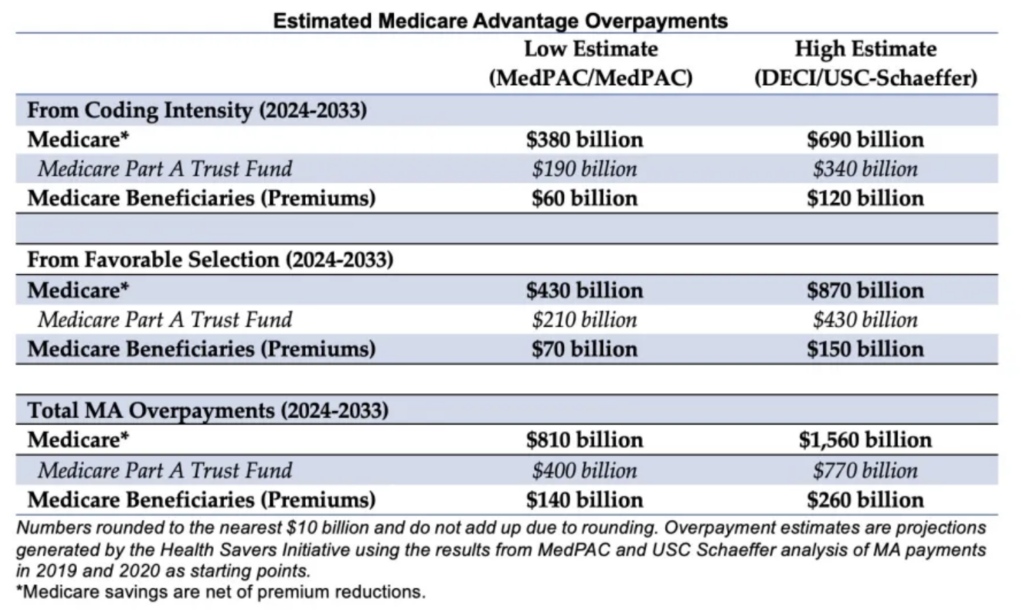

One study out of the University of Chicago estimates that enrollees in MA plans generated 6%–16% higher risk scores than they would have under fee-for-service Medicare, where risk scores do not affect reimbursement. Such upcoding leads to billions in overpayments per year. In fact, the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates CMS will overpay MA plans between $380 billion to $690 billion due to upcoding from 2024-2033. That’s $38-$69 billion per year!

Again, MA plans can squeeze out a ton of overpayments from CMS by upcoding/intensifying their diagnostic coding to create more HCCs per person. Just about every plan does this—they need to in order to stay competitive! Major insurers like UnitedHealthcare and Humana have already been sued for fraudulent coding.

Benchmark Setting “Favorable Selection”

Benchmark setting is a somewhat new area targeted for overpayments, as the Medicare population quickly enrolls in MA plans.

Benchmark rates are prone to selection bias. As MA enrollment rises in a county, traditional Medicare enrollment falls. This shift is concerning since benchmarks are based on traditional Medicare spending within that county. If MA attracts healthier individuals (which it does), the sicker beneficiaries remain in traditional Medicare. This leads to increased Medicare spending on traditional Medicare beneficiaries, which in turn raises the MA benchmarks and reimbursement. On the flip side, in areas with low MA enrollment, these plans can face underpayment.

One study from Health Affairs estimates that CMS overpaid MA plans around $9 billion per year between 2017 and 2020 due to this favorable selection in counties with high-MA penetration.

Dash’s Dissection

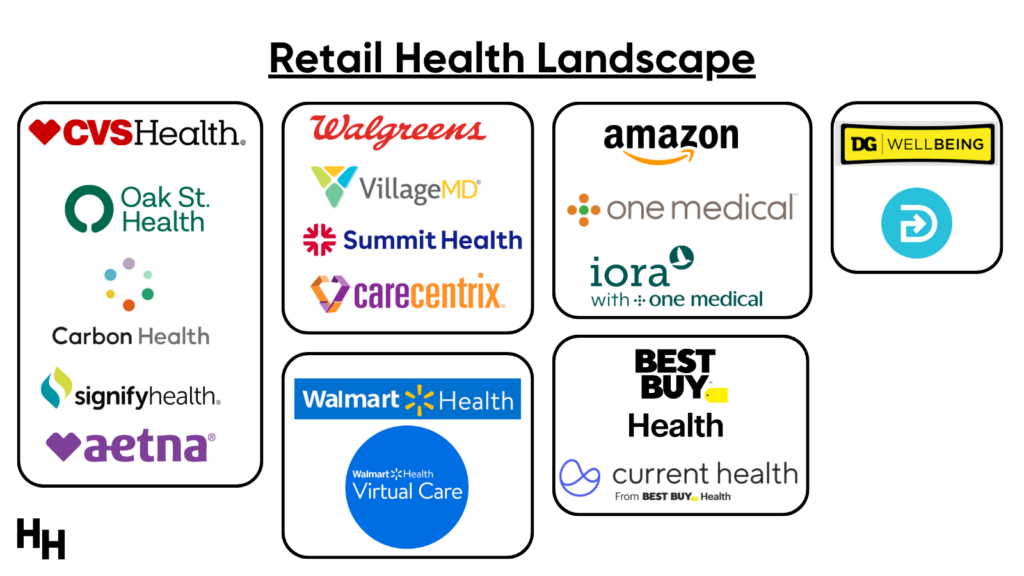

MA is undoubtedly a hot space with a lot of revenue potential (because of CMS overpayments). The whole “value-based care market,” which includes MA, is expected to be worth over $1 trillion by 2027. For this reason, corporations—mainly retailers like CVS, Walgreens, and Amazon—have flocked to the space through M&A activity.

Retailers’ mouths have been watering over the opportunity to tap into value-based care primary care (mainly MA). Capital raised for private investment in primary care increased 1000x from $15 million to $16 billion between 2010 to 2021. Further, retailers like CVS Health, Amazon, and Walgreens have reportedly committed $50 billion into primary care, equivalent to $50,000 per patient (read my takes here and watch my virtual event here).

Walmart is now the latest retailer trying to dive deeper into MA with rumors floating about the company acquiring MA primary care platform ChenMed (Blake covered it here).

My main concern: MA is costly for the government and taxpayers.

CMS continues to pay more for MA beneficiaries than for similar beneficiaries on traditional Medicare. What’s the point of value-based care if it costs more money than traditional fee-for-service Medicare with little to no improvement in quality of care? In fact, some researchers estimate MA will cost $75 billion more than traditional FFS Medicare in each of the upcoming years.

Here’s the bigger issue: now that large, powerful retailers have entered the MA space, they have massive political influence. Since money is involved, and retailers are making a lot of it through MA, taking such money away will be extremely difficult. I fear, as do others, that if CMS doesn’t correct these value-based care reimbursement models to limit overpayment and truly emphasize quality of care, it’ll be stuck using taxpayer money to fund MA with little improvement in the true quality of care. UnitedHealthcare already tried suing CMS for a rule requiring them to return billions of dollars in overpayments they received from CMS for incorrect diagnoses.

In summary, MA offers some benefits to beneficiaries and lucrative revenues for corporations, but inherent flaws lead to taxpayer costs. Major retailers, drawn to the potential profits, are diving into the MA market. However, without addressing MA’s issues, the promise of value-based care may result in higher costs without guaranteed quality improvements.

Stay ahead in healthcare with my weekly Healthcare Huddle newsletter, covering digital health, policy, and business trends for 30,000+ professionals. Share with colleagues and subscribe here.