19 November 2022 | Healthcare

Why Is the Emergency Department So Crowded?

By workweek

The expectation that you’ll wait hours in a crowded emergency department (ED) is an unfortunate but widely accepted norm. Who’s to blame for such overcrowding and long waits in the ED? Surprisingly… not the ED.

In this article, I’ll discuss what causes ED overcrowding and long waits, how these affect different stakeholders, and some solutions to address these critical issues.

The Deets

EDs across the nation are at a breaking point. This isn’t an understatement: emergency medicine physicians and societies jointly signed a letter to President Biden, urging his administration to investigate and find solutions to overcrowding in EDs.

The reason EDs are at a breaking point is not due to a new problem but rather a continuity of a well-known problem called “boarding.”

- Boarding occurs when patients are admitted to an inpatient unit but are kept waiting in the ED until an inpatient bed becomes available.

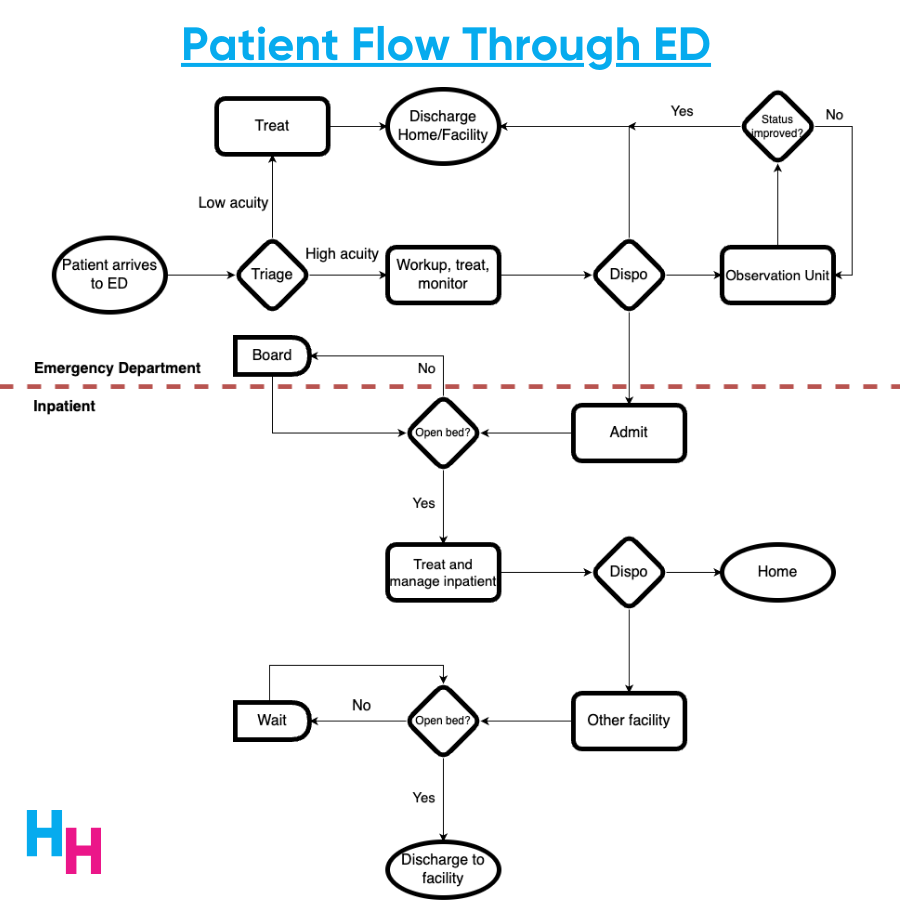

The high-level flow of patients through the ED is vital to understand in order to appreciate why boarding occurs. Patients arrive at the ED either by ambulance or self, with an undifferentiated presentation. A triage nurse quickly evaluates the patient and decides the acuity level: low or high. Low acuity patients typically get sent to an area of the ED where they can be quickly evaluated and discharged. High acuity patients are sent to another area of the ED where a full workup (EKG, lab tests, cardiac monitoring, oxygen) and monitoring will take place. Patients deemed “too” acute for the “acute zones” are sent to the resuscitation unit, where nurse-to-patient ratios are increased, and closer monitoring is available.

Once a full workup is complete, EM physicians must decide on a disposition plan for the patient. For example, will this patient be discharged home or to another facility (e.g., nursing home, SAR, another hospital)? Does this patient require less intense care but still need observation? Will this patient be admitted?

Why Boarding Occurs

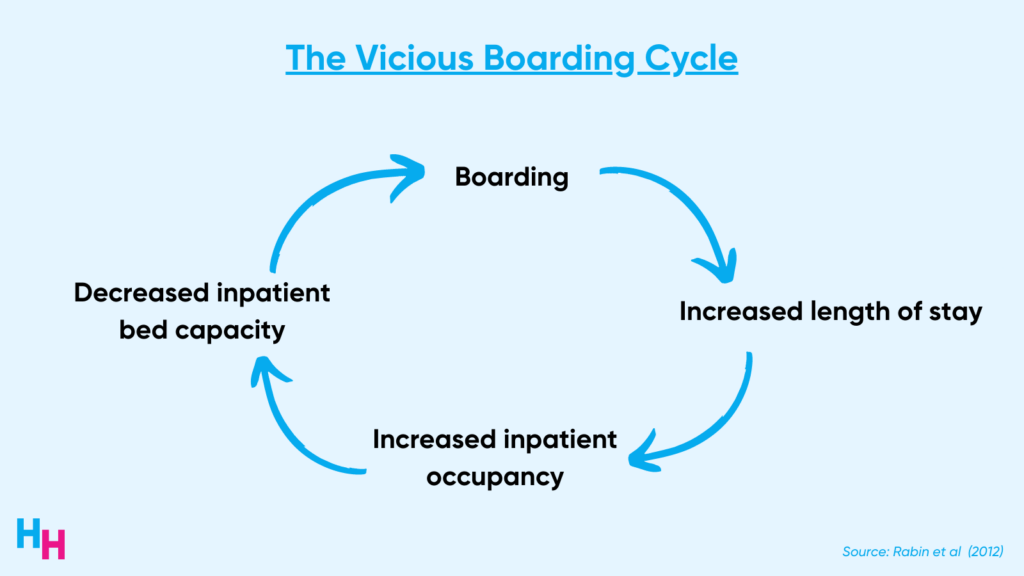

If a patient is to be admitted, an open bed is required. If no empty bed is available, the patient boards in the ED until a bed opens up. Fifty percent of boarders wait more than two hours for an inpatient bed, a proportion that likely underestimates current data. Boarding increases the length of stay in the ED and inpatient unit. When patients stay in the hospital longer, bed occupancy increases, and bed capacity decreases. Consequently, patients boarding in the ED have to wait longer for an available bed, and the ED becomes overcrowded. This is a vicious cycle.

Boarding is not caused by inefficiencies in the ED but rather inefficiencies in the hospital upstairs (the inpatient units). As I mentioned above, the bottleneck in the process is the availability of inpatient beds. If inpatient beds are available, then the process runs smoothly. If inpatient beds are unavailable, a bottleneck occurs, causing the process to become backed up, leading to boarding and overcrowding.

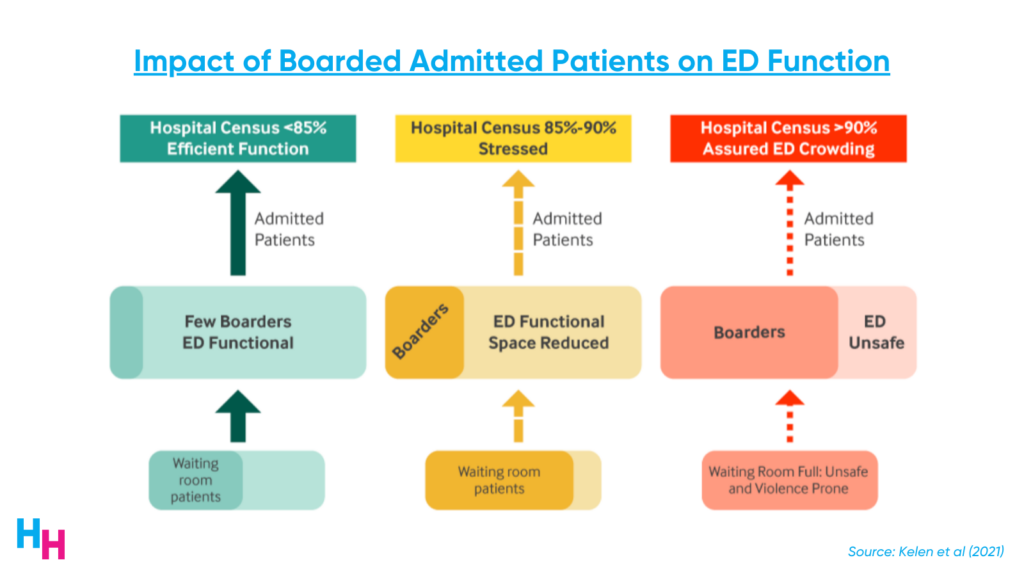

Data suggests that boarding occurs when the hospital census is above 85%. When the hospital census is between 85% and 90%, the process becomes a little backed up: patients begin to board, ED functional space is reduced, overcrowding occurs, and waiting rooms become backed up.

Once the hospital census surpasses 90%, the ED is in chaos. The number of boarders spikes, leading to severely limited ED functional space and extreme overcrowding. The ED is deemed unsafe, and physicians and nurses care for an unhealthy number of patients, leading to increased patient morbidity and mortality, and expediting provider burnout.

Hospitals across the nation, principally in metropolitan areas, are operating at above 85% capacity, many above 90% capacity. This means patients are boarding in EDs, and EDs are becoming dangerously overcrowded—so overcrowded that if there were a disaster (hurricane, earthquake, terrorist attack), EDs would not be able to tolerate the influx of patients needing medical care.

The pandemic has affected multiple upstream factors that have exacerbated the boarding problem in EDs. Some of these factors include staffing shortages and hospital economics.

Nursing homes have experienced severe staffing shortages, limiting the number of patients they can take care of from the hospital inpatient units. So, if around 12% of inpatients are typically discharged to a subacute rehab center or nursing home, they are taking up inpatient beds, waiting to be discharged, even though they’re medically cleared. In fact, while the average discharge process takes 7.5 hours, the discharge process takes an average of 35 hours for patients going to another facility (e.g., a nursing home). For this reason, the number of discharges has decreased, and the length of stay increased compared to pre-pandemic numbers.

Additionally, hospitals have been hemorrhaging money throughout the pandemic and continue to operate on razor-thin margins. So, anything that will increase revenue will dictate operations. ED patients are deemed “non-elective,” and the ED typically loses $700 per admitted patient. Hospitals will lose more money on these patients if they end up needing to be discharged to another facility (12% of them). Recall since facility space is limited, patients’ length of stay will increase as they wait to be discharged. Medicare reimburses hospitals by DRG—a fixed rate—so hospitals will lose money the longer patients stay.

Hospitals make money on elective patients needing specialized surgical or oncological care. Elective surgery patients, in particular, are typically insured, healthy enough to undergo surgery, don’t require intensive care, and have a more predictable hospital course. Therefore, hospitals will reserve inpatient beds for these elective patients. These are beds to which the ED cannot admit patients — “functional” hospital capacity is decreased, leading to increased boarding.

What Can Be Done?

The U.S. could draw inspiration from the U.K.’s successful “four-hour rule,” requiring 98% of ED patients to be seen, treated, and discharged (e.g., home or admitted) within four hours of entering the ED. If you’re an EM physician, you probably just scoffed reading that. Rightly so.

For U.S. EDs to achieve the four-hour rule will require changes at all touch points in the process. Here are some high-yield solutions:

- Extend primary care hours/availability (noting that PCP pay and other benefits would need to be increased. Burnout is a critical concern).

- Availability of after-care clinics with evening hours within 48 hours of ED discharge

- Hospital operations 24-7; smoothing elective admissions and surgeries (have surgeons operate on all days of the week instead of just earlier in the week)

- Opening unstaffed beds (these are the beds reserved for elective patients)

- Redistributing inpatient service beds (e.g., from surgery to medicine)

- Temporary boarding on inpatient hallways instead of ED hallways

Implementing these high-yield solutions is easier said than done. Why? Because hospital administrators are the ones in charge, and like all things in healthcare, nothing will change if money doesn’t flow. So, hospitals will lose money if they start opening unstaffed beds, typically reserved for revenue-driving elective patients. When thinking about such solutions, remember where the money is flowing and not flowing, and that’ll inform you of the likelihood that the solution will be implemented. This is the primary reason EM physicians are reaching out to President Biden for help.

In summary, EDs have become dangerously overcrowded because of an increasing number of boarding patients. The pandemic has exacerbated factors affecting boarding, such as staffing shortages and hospital economics, leading to limited inpatient bed capacity. Boarding is associated with increased patient morbidity and mortality and provider burnout. There are several high-yield solutions to address boarding, but if these solutions don’t drive hospital revenue, they’re unlikely to be implemented.

Read part II here!

If you enjoyed this deep dive, share it with colleagues. Sign up for the Healthcare Huddle newsletter here.