03 December 2022 | Healthcare

Part II: Why is the Emergency Department So Crowded?

By workweek

Emergency departments across the country are at a breaking point. They’ve become dangerously overcrowded due to a well-studied phenomenon called boarding.

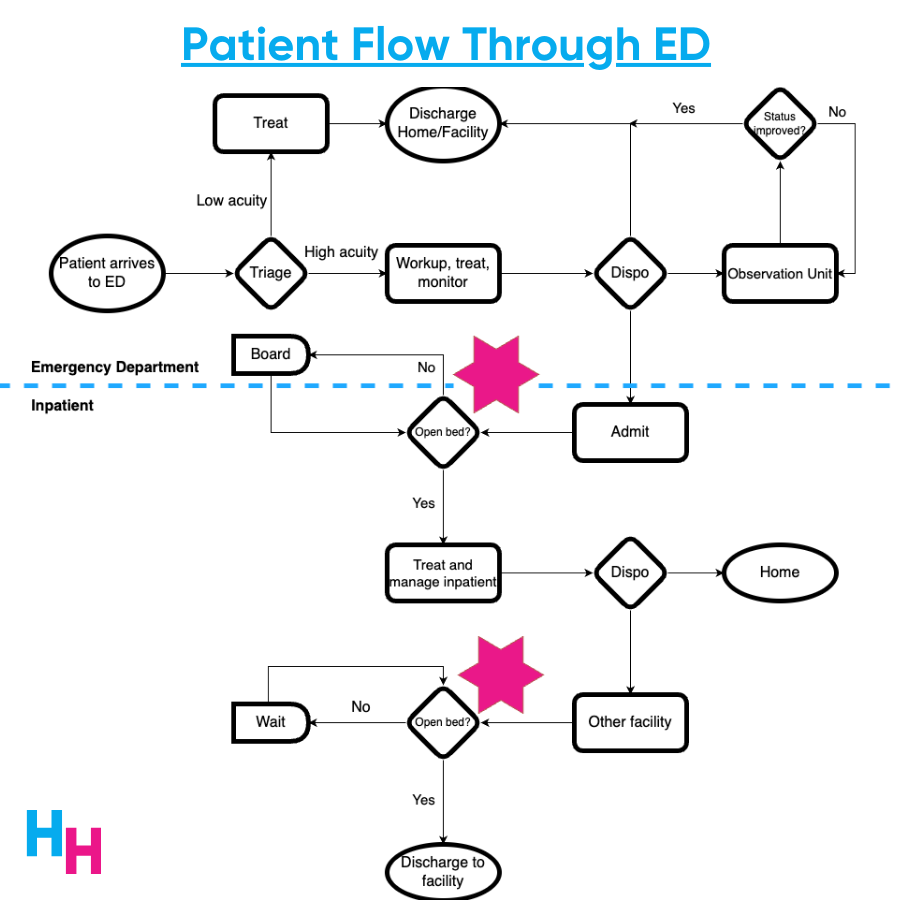

Boarding occurs when patients are admitted to an inpatient unit but are kept waiting in the ED until an inpatient bed becomes available.

I discussed the boarding problem a couple of weeks ago, shedding light on why boarding exists and its impact on patients and physicians. However, I should have noticed an important aspect of boarding: psychiatric patients.

In this article, I’ll quickly recap the boarding problem, discuss boarding as it relates to psychiatric patients, and touch on solutions to alleviate the boarding of psychiatric patients.

The Boarding Problem

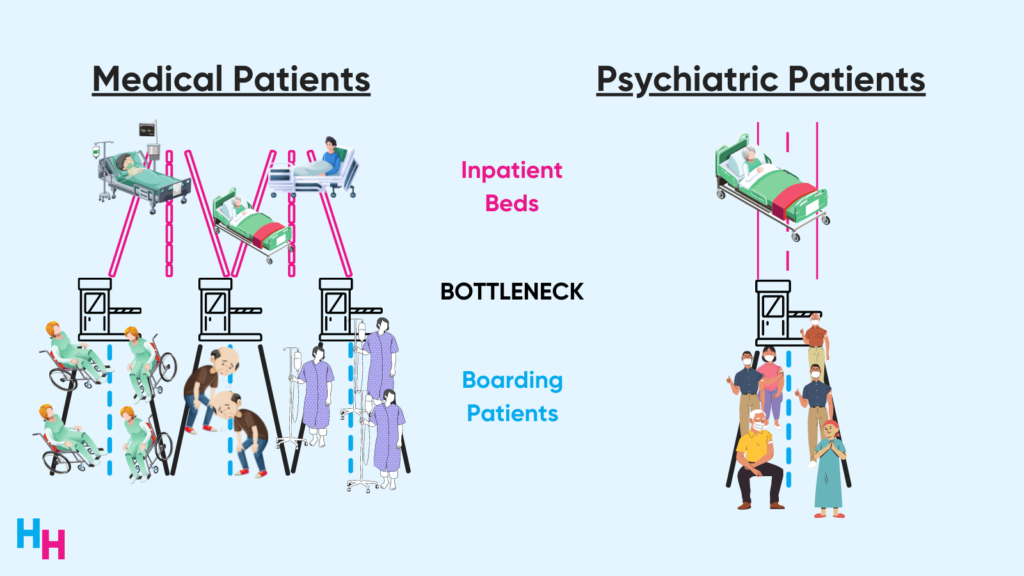

A classic bottleneck phenomenon causes the boarding of patients in the emergency department. If a patient is to be admitted to an inpatient unit for further medical or psychiatric workup, an open bed is required. If no empty bed is available, the patient boards (waits) in the ED until a bed opens up—the bottleneck.

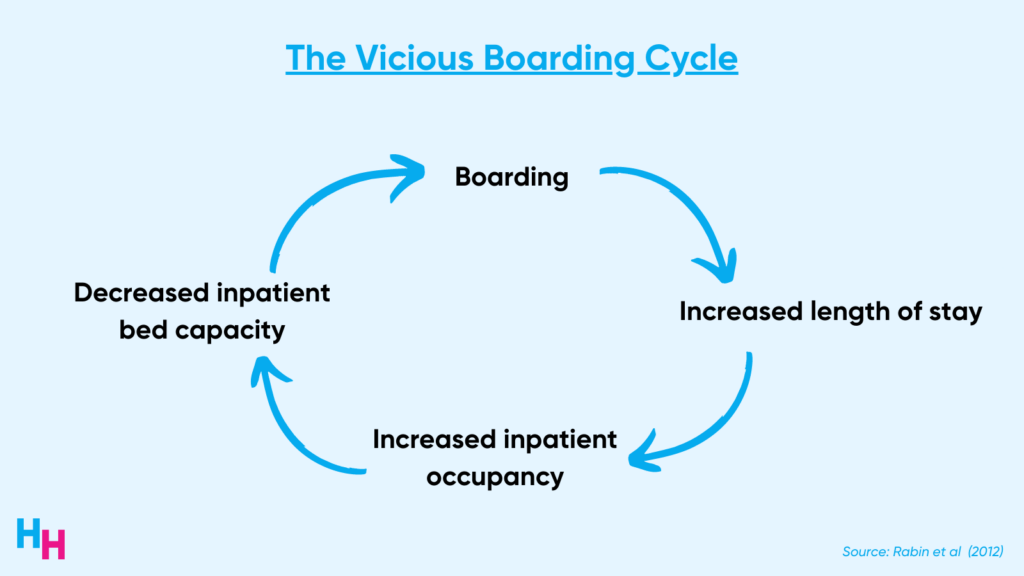

Boarding increases the length of stay in the ED and inpatient unit. When patients stay in the hospital longer, bed occupancy increases, and bed capacity decreases. Consequently, patients boarding in the ED have to wait longer for an available bed, and the ED becomes overcrowded.

The Boarding of Psychiatric Patients

Psychiatric ED patients have around five times higher odds of boarding than non-psychiatric ED patients. This makes sense since patients presenting with an active psychiatric illness are more than two times more likely to be admitted than those presenting with medical issues. For example, one study found that 41% of patients presenting to the ED with mental health or substance use issues were admitted.

The causes of boarding I discussed in my previous newsletter also apply to psychiatric patients: there are not enough beds for psychiatric ED patients who are to be admitted. But, the boarding problem is significantly worse for psychiatric patients than medical patients, even though psychiatric patients make up just 4% of all ED visits. Why? Psychiatric bed capacity is severely limited.

Psychiatric bed capacity declined 77% from 1970 to 2014—a total of 500,000 beds… gone. One major reason for the decline is changes in where patients with acute psychiatric needs are receiving care, including community-based outpatient services like Assertive Community Treatment (ACT).

Hospitals have since become increasingly ill-equipped to provide psychiatric care for ED patients. In one study surveying 2,400 hospitals, only half had a psychiatrist on staff or available to provide consultation. Even worse: of the rural hospitals surveyed, 70% had no psychiatric services. Additionally, around 60% of the surveyed hospitals said they transfer ED patients with active psychiatric issues in need of admission to a different hospital. Sixty percent!

The lack of inpatient bed capacity is a cause of boarding for both medical and psychiatric patients in the ED. However, while the rate of total ED visits has remained relatively stable over time, the rate of ED visits for patients with psychiatric needs continues to increase. One study found ED visits for suicidal ideation—a presentation requiring extensive workup and likely admission—increased 400% between 2006 and 2014. It’s well documented that ED visits for suicidal ideation or attempt continue to increase. Additionally, ED visits for drug overdose increased by 30% during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic, a number that’s only growing.

Hospitals, therefore, have an increasing influx of psychiatric patients needing psychiatric beds, but there’s a bed capacity bottleneck. This causes boarders waiting for inpatient psychiatric beds to wait three times longer on average than non-psychiatric boarders.

The Impact of Boarding Psychiatric Patients

The boarding problem of psychiatric patients uniquely affects patients, providers, and hospitals.

Psychiatric patients boarding in the ED receive suboptimal care. Recall that 50% of hospitals don’t have an available psychiatrist on staff or available for consult. Therefore, EDs don’t have the expertise or resources to care for psychiatric patients. Psychiatric patients are also more likely to decompensate in the chaotic ED, thus putting them at increased risk of needing chemical and physical restraints.

Additionally, because of the scarce number of psychiatric beds, psychiatrists practice reverse triaging. Essentially, once psychiatric patients are even the slightest bit stabilized, they’re discharged back to the same environment from which they came. This opens a bed for higher-risk psychiatric patients. The practice of reverse triaging leads to the revolving door effect, where the same psychiatric patients come in and out of the ED and inpatient psychiatric care.

The stress of managing overcrowded EDs exacerbates physician burnout. Now, add an increased risk of workplace violence—which is common from patients involuntarily held for psychiatric reasons—to increased ED crowding, and you have worsening physician burnout. Emergency physicians also face moral distress, where they know they need to care for these psychiatric patients but don’t have the specialized training to do so.

Lastly, hospitals face a financial burden from boarding psychiatric patients. According to one study at a single tertiary care hospital, hospitals lost a total of $2,400 per psychiatric patient boarding in the ED, which equated to a 40% decrease in physician reimbursement. The researchers found that psychiatric patients boarding in the ED (notably longer than non-psychiatric patients) prevent an additional 2 patients from being cared for. The financial loss is likely a conservative estimate, given EDs across the nation are now functioning at max capacity.

Dash’s Dissection

What differentiates the boarding I discussed in a previous newsletter from psychiatric boarding is the influx of psychiatric patients. The reason for the influx of such patients is complex, yet simple: mental health care in the US has been overlooked and abysmally underfunded. If patients can’t receive adequate and accessible care for their depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, substance use, or schizophrenia, where will they turn to for care?

The emergency department.

The profound lack of both inpatient and outpatient psychiatric and substance use services, and the labyrinthian processes for psychiatric services driven by byzantine insurance coverage, have placed extraordinary pressure on EDs. — Kelen et al (2021)

Ways to alleviate the boarding issue for psychiatric patients are similar to those I discussed previously, including opening unstaffed beds (these are the beds reserved for elective patients) and redistributing inpatient service beds (e.g., from surgery/medicine to psychiatry). However, focusing on more upstream causes of boarding, such as inadequate access to mental health care services, will also help. This includes increased funding into community-based resources that will increase access to therapy and rehab centers. Funding can also go to comprehensive crisis systems that provide quick stabilization in the community for acute psychiatric conditions.

To add fuel to the fire, New York City Mayor Adams announced a plan to involuntarily hospitalize those with homelessness who have untreated severe mental illness. Given the information I discussed, this plan will fail miserably without adding additional resources to increase bed capacity and other tools to treat these patients.

NYC hospitals are already at capacity. Adding an influx of psychiatric patients who will only receive suboptimal care will cause more harm than good, especially if these patients are thrown right back on the street (do you remember reverse triaging?). A better plan would be investing money into community-based mental healthcare services—the upstream factors.

In summary, EDs across the country have become dangerously overcrowded due to a well-studied phenomenon called boarding. Psychiatric patients in the ED are more likely to be admitted and face longer boarding times because of a severe psychiatric bed shortage and increase demand for inpatient psych beds. EDs are ill-equipped to manage psychiatric patients, leading to suboptimal care. More funding for community-based mental healthcare services is needed to increase access to effective mental healthcare resources.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, share it with colleagues. Sign up for the Healthcare Huddle newsletter here.