26 January 2024 | FinTech

Save Me From the Subscription Economy!

By Alex Johnson

Let’s start with this 2022 headline from The Verge, which caused my nervous system to temporarily fritz out when I first read it:

If there’s a dark side to the trend, most memorably observed by Marc Andreessen, of software eating the world, it’s this.

In 2020, BMW introduced a new version of its operating system that enabled subscriptions and other microtransactions. As The Verge article points out, this change led to some rather disturbing business “innovations” from the car maker:

Carmakers have always charged customers more money for high-end features, of course, but the dynamic is very different when software, rather than hardware, is the limiting factor.

In the case of heated seats, for example, BMW owners already have all the necessary components, but BMW has simply placed a software block on their functionality that buyers then have to pay to remove. For some software features that might lead to ongoing expenses for the carmaker (like automated traffic camera alerts, for example), charging a subscription seems more reasonable. But that’s not an issue for heated seats.

Other features that BMW is locking behind subscriptions (as per the company’s digital UK store) include heated steering wheels, from $12 a month; the option to record footage from your car’s cameras, priced at $235 for “unlimited” use; and the “IconicSounds Sport package,” which lets you play engine sounds in your car for a one-time fee of $117.

BMW eventually relented on charging subscriptions for heated seats and steering wheels after a significant customer outcry, but the overall trend is alive and well. Software has unlocked the ability for companies to make literally everything a subscription, and this shift, which investors and business executives have cheered, is wreaking havoc on their customers’ finances.

Banks and fintech companies should focus on helping consumers fight back.

The Subscription Economy

Here are some quick facts about the subscription economy:

- It’s big, and it’s growing. In March of 2021, UBS estimated the digital “subscription economy” would grow from $650 billion in 2020 to $1.5 trillion by 2025. I haven’t been able to find any good data confirming how close we are to that $1.5 trillion figure here at the start of 2024, but if my personal experiences as a consumer of countless subscription services are any indication, we’re likely making good progress.

- It’s growing beyond consumers’ control. A spring 2022 survey by C+R Research found the average American spends $133 more on monthly subscriptions than they estimate — $219 versus $86. unsurprisingly, 42% said they had forgotten about a subscription they were paying for but not using and a third planned to cut back on subscription spending.

- It’s an attractive business model. Zuora, which coined the term “subscription economy” in a 2015 pitch deck, has been tracking the performance of more than 500 subscription-based businesses in its Subscription Economy Index (SEI) for the last 12 years. During that time, it found that SEI companies grew their revenue 3.7x faster than the companies in the S&P 500.

That last fact should obviously be taken with a large grain of salt, given Zuora’s incentives to promote the health of the subscription economy, but still, the larger point stands – subscriptions are a very attractive business model.

There are a few reasons for this:

- Companies like recurring revenue. Recurring revenue streams are easy to model out into the future, which makes it easier for companies to justify internal investments (R&D, headcount, geographic expansion, etc.) as well as for external investors and lenders to justify giving the company money (revenue-based financing for subscription and SaaS businesses has been a big area of growth in fintech in recent years).

- Retention is cheaper than acquisition. This was especially important during the ZIRP years, when ample VC dollars drove up CAC for everyone. It’s cheaper to acquire a customer once and manage churn than to continually re-acquire customers every month.

- Customer inertia is highly profitable. Look at those stats from C+R Research again. A large portion of consumers are paying for subscriptions that they have forgotten about or meant to cancel but never did. Economists at Stanford and Texas A&M studied this phenomenon and found that consumers’ forgetfulness when it comes to subscriptions can boost companies’ revenues by up to 200%.

- Dark patterns are tempting. And if customers actually try to cancel their subscriptions, they often find it to be significantly more difficult or inconvenient than it was to sign up for them in the first place. This isn’t an accident. A report released by the FTC in 2022 found that companies are increasingly using sophisticated design practices (“dark patterns”) in order to stymie consumers’ efforts to cancel subscriptions. If you’ve ever tried to cancel a Wall Street Journal subscription, you’ll know what I’m talking about.

- Subscriptions generate data. In addition to its attractiveness as a business, subscriptions also stimulate ongoing customer engagement, which generates data. This data can be used by companies to personalize customers’ experiences and make tailored product recommendations. Or, in some cases, the data can create entirely new business lines. Amazon is a good example here. It used its Prime subscription service (which, back in the day, actually did provide true free two-day shipping and ad-free video on demand) to hook consumers into becoming repeat customers and then used the resulting first-party data to bootstrap its own advertising business (which happened just as third-party cookies started getting phased out).

This is why consumers are being slowly drowned in an ocean of subscription services. It’s good business.

And it’s not just consumers.

SaaS Subscriptions Are a Problem in B2B

The B2B equivalent to this B2C subscription problem is software-as-a-service (SaaS).

According to Gartner, worldwide SaaS spending will grow to more than $232 billion in 2024, up from $167 billion in 2022.

What’s driving this explosive growth?

Put simply, SaaS products are easy to adopt.

You can pay for them with a company credit card (and many offer free trials). You can begin using them without IT. There are hundreds of thousands of different SaaS solutions, covering every conceivable function and use case. And they are constantly and passively updated, so you have access to the latest features without having to undergo time-consuming, disruptive updates.

However, this ease of adoption is also a problem. According to a study by Vendr, companies are using an average of 130 SaaS apps. Many of these apps are redundant with ones being used by employees in other departments. Others have unused licenses (or have been abandoned entirely). And even for SaaS apps that aren’t redundant and are being fully utilized, the price being paid by the company is often too high due to a lack of negotiation by a centralized procurement function.

And it’s not just the SaaS apps. It’s the entire tech stack, all the way down to cloud computing, which, according to Gartner, is estimated to make up 14% of enterprise IT spending worldwide in 2024 – up from 9% in 2020.

Fortunately, an entirely new field – financial operations or FinOps – has sprung up in the last five years, focused on helping companies align their cloud and SaaS spending with their desired business outcomes.

There are now a myriad of different platforms and products out there (offered by companies like CloudZero, Vendr, Anodot, Zluri, Vertice, and Productiv) designed to put FinOps principles into practice and bring transparency and control to companies’ cloud and SaaS spending.

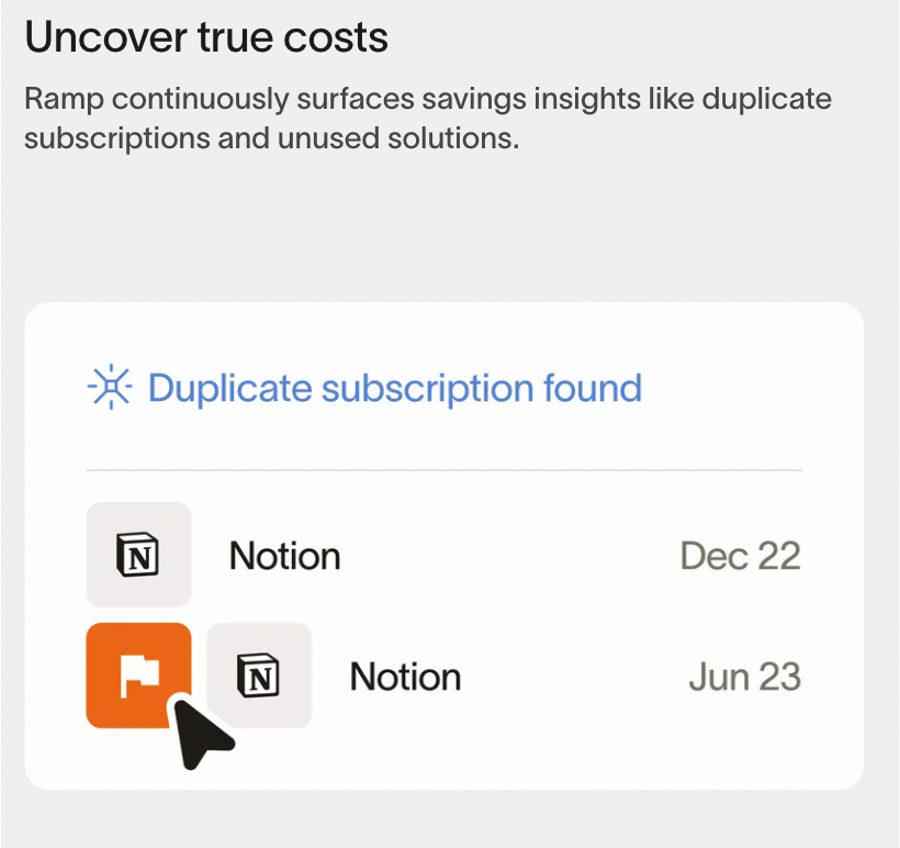

This need has become so important that even broader expense management providers, like Ramp, have jumped in:

Which brings me back to a question that I have asked multiple times in this newsletter – why is there no Ramp for consumers?!?

Where’s My Ramp for Consumers?

I know. I know. We have some Ramp-like stuff for consumers in this area already.

We have Truebill (now Rocket Money), which utilizes open banking to analyze your transaction history, identify recurring transactions, and help you cancel unwanted subscriptions.

We have Trim (now owned, interestingly, by OneMain Financial), which works in a similar fashion to Rocket Money, but with more of a focus on helping you negotiate better rates on your bills (a feature that Rocket Money also offers).

We have X1 (acquired by Robinhood), which provides users with the ability to generate an unlimited number of virtual cards, including time-limited and single-use cards for use in free trials and subscriptions:

These products and features are all steps in the right direction, but they don’t, by themselves, solve the problem.

Truebill deserves credit for recognizing the urgency of the subscription economy problem early on, but as a long-time user of the service, I can tell you that it has never worked perfectly. Using bank transaction data to identify recurring transactions isn’t a foolproof approach. The quality of the underlying data just isn’t good enough (yet) to reliably identify 100% of a consumer’s subscriptions. Additionally, it’s not always possible for Rocket Money or Trim to efficiently cancel or negotiate down all of a consumer’s bills and subscriptions. Companies go to extraordinary lengths to make that an inefficient and unautomatable process. And the X1 virtual card feature (which some large bank issuers like Capital One also offer) is neat, but of little practical value if it’s not paired with a broader set of subscription management capabilities.

Why has no one (particularly a large retail bank) pulled all of this together into a service that fully solves this problem?

What’s the Difference?

I think part of the challenge is that banks often get confused about the difference between a bill and a subscription.

Banks tend to look at it in terms of capturing and retaining payment volume. They see subscriptions as small recurring payments that they’ve already captured (through their debit cards or credit cards) and that they have no incentive to help their customers reduce or eliminate. They see bills as large recurring payments that they don’t directly control (the vast majority of bills are paid by consumers working directly with the billers) and that are increasingly being paid using less profitable payment rails (the wireless carriers have been particularly aggressive about this lately).

Thus, banks have little interest in building better subscription management capabilities but a lot of interest in building bill payment solutions (which they’ve been trying and failing to do for decades).

If banks bothered to think about this question – What’s the difference between a bill and a subscription? – from their customers’ perspective, they might come up with an answer more like this:

Bills are recurring financial obligations tied to products or services that deliver a steady, unchanging level of value to consumers. Banks should do everything they can to ensure that their customers are able to pay their bills on time every month and help their customers (where possible) to negotiate better rates for them.

Subscriptions are recurring financial obligations tied to products or services that deliver a variable or uncertain level of value to consumers. Banks should do everything they can to help their customers keep track of their subscriptions, constantly evaluate and prioritize their value, and cancel them where necessary.

What I Want

I want a subscription command center.

When I open up a new debit card or credit card account, I want the provider to ask me to connect all of my existing bank and card accounts so that it can do a first pass at identifying all of my recurring transactions. I then want to be able to finalize my list of subscriptions manually, removing any mistakes and adding any ones that got missed. Then I want to leverage a card-on-file update service (powered by a provider like Knot) along with my provider’s virtual card issuing capability (powered by a provider like Lithic) to assign a unique virtual card to every subscription service that I currently use.

The subscription command center should be a centerpiece of my provider’s mobile app, allowing me to see all my subscriptions in one place (including how they fit into my overall budget and monthly cash flow) and to cancel them (by deactivating a virtual card) or sunset them (by setting a deactivation timeline for a virtual card) with the push of a button.

As a bonus, it would be nice if I could give my provider access to my email account so that it could monitor marketing messages from the providers of subscription services that I canceled (Please, we want you back. Here’s a special offer!) and notify me if there’s a particularly compelling offer that I might want to consider.

One More Thing …

[Steve Jobs voice] There is one more thing I wanted to talk about today …

Apple should really be the one to build this subscription command center of my dreams.

In addition to being able to deliver everything described above, which would be a neat way to relaunch the Apple Card (post-Goldman Sachs) and to revamp the Apple Wallet (which desperately needs it), Apple has a few unfair advantages in this area that it should absolutely exploit.

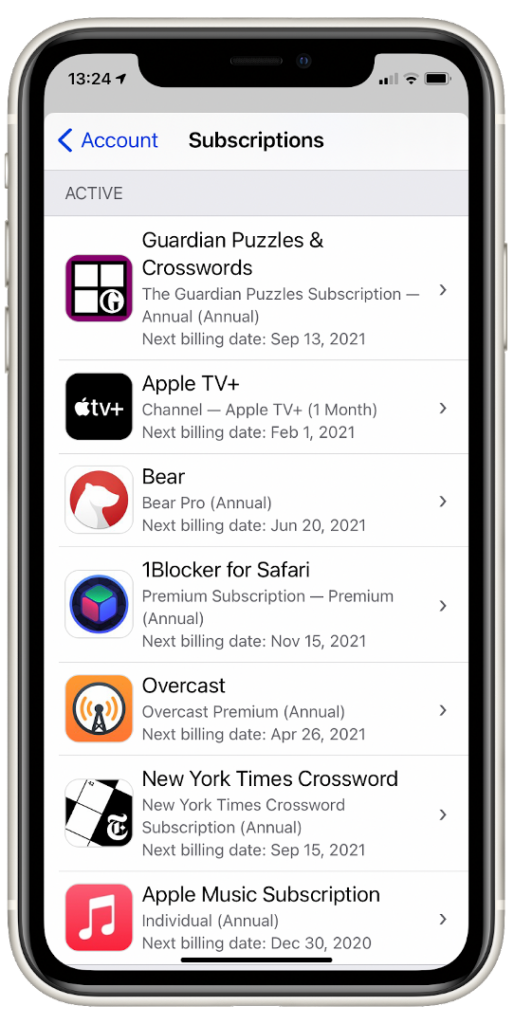

First, Apple already offers the capability, buried deep within its Settings app, for users to manage all of their subscriptions tied to their Apple ID. Users can see all of their subscriptions in one place, cancel unwanted active subscriptions, and reactivate dormant subscriptions, all with just a few taps:

Second, given Apple’s unique OS and device-level access to its customers’ lives, I would think it would be fairly simple for the company to further enrich its subscription management capabilities by looking at usage data. In the same way that my iPhone can give me a report on my screen time, couldn’t it also give me a report (or proactive notifications) based on my usage of the different apps and services I subscribe to through the Apple ecosystem in order to help me identify and cancel subscriptions that I’m not fully utilizing?

Apple should be the one to do this, but please, somebody – Apple, Rocket Money, Capital One – anybody, save me from the subscription economy!