12 January 2024 | FinTech

The (Unlikely) End of the FICO Score

By Alex Johnson

My first house was a bit of a fixer-upper. My wife and I knew this going in. It was built in 1939 and it had been, for the two decades before we bought it, mainly used as a rental property for college kids.

We knew we were signing up for a lot of work (and boy, did we do a lot of work), but we were also hopeful that we wouldn’t run into any major structural problems. We’d gotten an inspection before purchasing it, and it hadn’t revealed anything significant.

But home inspections don’t catch everything.

Towards the end of our time in the home, we embarked on a major remodel, which involved removing a load-bearing wall and replacing it with a large beam. In the midst of these structural changes, our builder made an interesting discovery – the rafters for our house, the things that hold up the roof, weren’t nailed together properly!

This was an alarming discovery, and I remember asking our builder, “How bad is this? Is my roof going to collapse?”

“Probably not,” he said. “It has lasted this long. If we weren’t messing with anything, it would probably last for another 100 years. But we are messing with a bunch of stuff, so now we need to fix it.”

What my builder was referring to is known as the Lindy Effect – the theorized phenomenon that the longer a period something has survived to exist or be used in the present, the longer its remaining life expectancy.

It’s a compelling, if somewhat unintuitive, idea – just because something is old doesn’t mean it’s not useful or robust; in fact, the older something is, the more likely it is to be especially useful or robust.

This applies to all kinds of different things. Roofs. Business Models. Recipes. COBOL code. Marriages. Ideas.

The Lindy Effect is everywhere!

However, my builder’s caution applies broadly as well – when you mess with something that has been around for a long time, when you alter the foundation that it rests upon, you should be prepared for its future life expectancy to change too.

I’ve been thinking about this recently in relation to the FICO Score.

Disclosure – the remainder of this essay is about FICO and the FICO Score. I worked at FICO, on the software side of the business, between 2016 and 2021, and I have worked for nearly 20 years in close proximity to FICO and the credit bureaus. As is eternally the case here at Fintech Takes, nothing I write is based on proprietary information, nor should it ever be construed as investment advice.

A Quick History of FICO and the FICO Score

Fair, Isaac & Co. was founded in 1956 by William Fair (an engineer) and Earl Isaac (a mathematician). Fair and Isaac met at Stanford Research Institute, where they worked on operations research for the military. Their goal in founding the company that would eventually be called FICO was to find a non-military use for their expertise in statistical analysis.

In 1958, the same year that Bank of America unleashed the general-purpose credit card onto the citizens of Fresno, California, they found it – credit scoring.

FICO developed a scorecard that could accurately predict a person’s creditworthiness based on their past behavior.

Of course, today, this doesn’t sound all that special. However, in 1958 it was so special, so unusual, that banks didn’t really see the value. There were a few reasons for this.

First, lenders had been using humans to make credit decisions for centuries. There was a deep-seated belief in the effectiveness of this “shake-their-hand-and-look-them-in-the-eye” approach and (as we still see in banking today) a corresponding skepticism about innovation.

Second, it was expensive. At the time, FICO’s approach to credit scoring was consultative – they would go into each lender, one at a time, and manually build a custom scoring model for them using the lender’s own internal customer data.

Fortunately, the federal government stepped in.

Congress passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) in 1970, which established a formal regulatory regime for the emerging credit bureau market, and the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) in 1974, which prohibited lenders from discriminating against applicants on specific identity-based characteristics like race.

The combination of FCRA and ECOA dramatically altered the lending ecosystem in ways that were enormously beneficial for FICO. Specifically:

- The prohibition against discrimination strengthened the case for algorithmic credit decisioning. Lenders’ reluctance to embrace credit scoring models melted away when they discovered that the use of such models (in place of human underwriters) would make it much easier to demonstrate their compliance with ECOA and generate compliant adverse action notices for consumers who were declined for credit.

- A more structured credit reporting market opened the door for FICO’s big business model shift. In the wake of the FCRA, the credit reporting market quickly consolidated down to the three national credit bureaus that we have today. The credit bureaus rapidly adopted electronic databases during that time as well. This combination made it feasible for FICO to build a score based solely on credit bureau data, which it did for First National Bank of Kansas in 1984. This was followed by the official release of the first general-purpose consumer credit score – the FICO Score – in 1989.

That second development was a huge turning point for FICO because it completely eliminated the incremental cost associated with delivering a credit-scoring model to a new client.

Credit scoring was transformed from a consulting business to a SaaS business.

This was enormously profitable for FICO, which IPOed in 1989. At the time, the company generated just $18 million in revenue. By 1995, it was $114 million, with a significantly higher profit margin, thanks mainly to the FICO Score and the company’s distribution arrangements with the credit bureaus and major credit card processors.

And in 1995, FICO was blessed by the government with more good fortune – the FICO Score became the standard credit scoring model used to underwrite and securitize conforming mortgages (i.e., mortgages that can be sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac). By 2000, 75% of all mortgage applications in the U.S. were decisioned using the FICO Score.

The result of all these developments has been an incredible 35-year run, with FICO’s stock compounding 20% year over year since its IPO and the company maintaining a hold on roughly 80-90% of the consumer credit scoring market in the U.S.

Put simply, FICO is, along with Visa, PayPal, and a few others I’m forgetting, one of the most successful fintech companies ever.

Why Everyone Believes the FICO Score is Unassailable

A while back, I posted the following prediction on Twitter and LinkedIn:

The FICO Score, as a mechanism for establishing a common understanding of a consumer’s creditworthiness, will be dead within the next ten years.

The implications for credit monitoring, PFM, and loan securitization are immense.

The pushback I received from folks in the fintech ecosystem in response to this post was immediate and forceful, like what you’d get if you suggested to crypto bros that Gary Gensler is actually a really good guy.

Now, admittedly, the wording of my post was a bit hyperbolic, and the ten-year timeframe was quite aggressive, but still, I was surprised. Why were fintech folks, who are no strangers to hyperbole and who are generally very open to the idea of disruption, so dead-set against the possibility of the FICO Score’s influence waning over the next decade?

The answer, of course, is that many many people have predicted this same thing over the last 30 years, and it has never happened. Not when Capital One invented risk-based pricing in the 1990s. Not when the VantageScore was launched by Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion in 2006. And not when truckloads of fintech lenders – P2P lenders, BNPL providers, and everything in between – popped up in the 2000s and 2010s claiming that they had built big data-powered, AI-supercharged underwriting models that would render the FICO Score obsolete.

Through all of it, the FICO Score has just kept chugging right along, the Lindy Effect holding strong.

So, case closed, right? If the FICO Score has survived this long, under this level of public and competitive scrutiny, it’ll just keep on keeping on for the foreseeable future, right?

Maybe!

Or maybe not.

After all, the Lindy Effect isn’t perfectly predictive. Everything fades away eventually. And in the case of my specific prediction, I think folks glossed over a key part – “The FICO Score, as a mechanism for establishing a common understanding of a consumer’s creditworthiness, will be dead within the next ten years.”

I wasn’t talking about the FICO Score as an analytic model. I was talking about the FICO Score as an industry standard. And as Marc Rubinstein wrote in his excellent article on FICO (which you should absolutely carve out some time to read), “Fair Isaac sells a standard not a prediction tool, and displacing standards is hard.”

That’s very true, but I think there are a few reasons why it might happen anyway, and sooner, perhaps, than most folks would imagine.

Why This Time Probably Won’t Be Different (But Might Be)

I’ll make my case in four parts, and by looking at the value that the FICO Score provides through four different lenses.

#1: The FICO Score as an Analytic Tool

Let me start off by being extremely clear – the FICO Score is the single best general-purpose analytic tool for rank ordering the probability of credit default within the U.S. adult population.

This shouldn’t come as a shock to anyone, given that FICO invented the credit score, but it bears stating explicitly. The FICO Score is extremely good at what it does and the credit risk management expertise and institutional memory inside FICO is second to none. The FICO Score provides a tremendous amount of analytic value to lenders across the credit lifecycle, from marketing and origination through account management and collections.

Now, having said that it’s also important to acknowledge that, unlike in 1958, FICO’s expertise in credit scoring is not, today, uniquely valuable.

Lots of smart people (empowered by technology that Fair and Isaac would have killed for) can and do build credit scoring models that are roughly as good at rank ordering probability of credit default as FICO is.

The VantageScore, built by the three credit bureaus, is about as good as the FICO Score (one piece of proof – Synchrony Bank switched from FICO to Vantage in 2021).

All of the big banks (which account for the majority of consumer lending volume in the U.S.) have built their own custom credit scoring models, using a combination of bureau data and attributes, external scores like FICO, and proprietary internal data and attributes. These models don’t generally outperform FICO on an industry-wide basis, but they do outperform FICO for their banks’ target customer segments (which is obviously what the banks care about).

Even fintech lenders, which often start out being way too confident in their ability to build an underwriting model that can outperform FICO, eventually accumulate enough performance data and credit risk management expertise to be able to build superior custom models for their own products and portfolios.

This, by itself, isn’t necessarily a problem for FICO (nor a condemnation of the FICO Score as an analytic tool).

The problem is when it comes to upgrades.

All predictive models become less useful over time. It’s inevitable. Consumer behavior changes, often in response to unforeseeable macro events or new technology. For example, when online lending started to really boom in the U.S. in the middle of the 2010s, lenders noticed that consumers’ credit scores were seeing these weird boosts that weren’t actually indicative of improved credit performance. It turns out that consumers were using those personal loans from digital non-bank lenders to refinance and pay down their revolving credit card debt, which would temporarily spike those consumers’ credit scores (lower utilization!) before they would load back up on more credit card debt. The FICO Score was fluctuating in ways that were confusing to lenders because of consumer behavior that emerged after FICO developed its score.

FICO addresses this challenge by releasing new versions of its score on a regular basis (every five years, on average). FICO 10, for example, was released in 2020 and, among other changes, treats personal loans used for debt consolidation differently in order to fix the problem lenders had been seeing with older versions of the score.

The trouble is that very few lenders use FICO 10. Nor do they use FICO 9, which was introduced in 2014 and includes all kinds of nice changes like decreasing the impact of medical collections and including rent payment data.

The most commonly used version of the FICO Score, for non-mortgage lending decisions, is FICO 8, which was released in 2009. For mortgage lending decisions, FICO 2, 4, and 5 are all still commonly used.

You can understand why lenders (especially large ones) are forgoing upgrades. Why pay more money for a newer version of a score that will be a pain to migrate to and that you don’t really use much anyway?

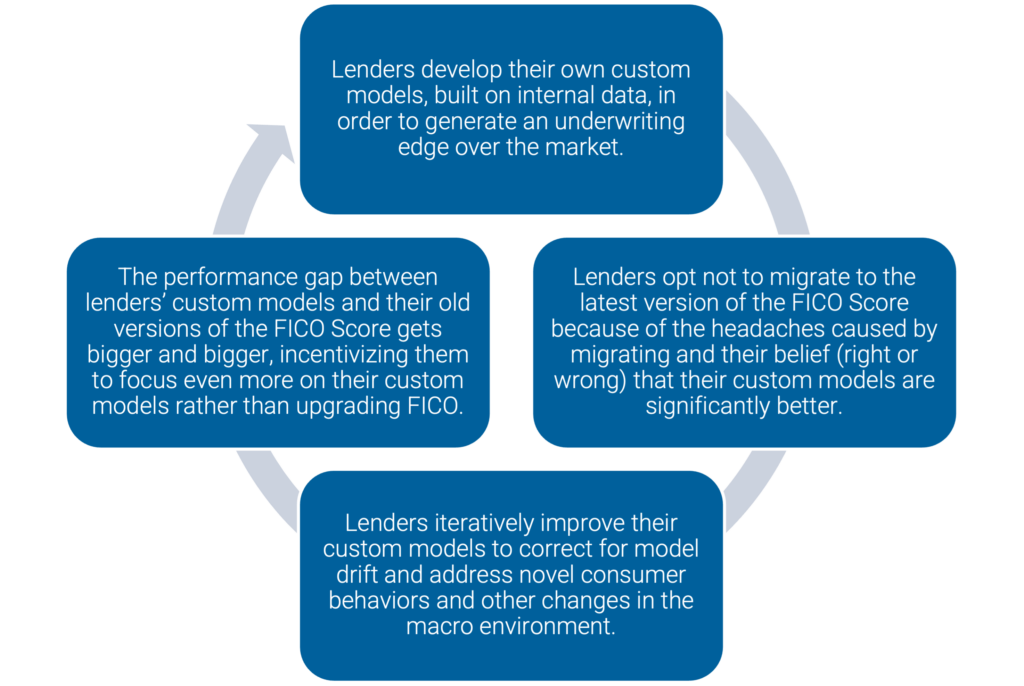

However, from FICO’s perspective, this is a very bad self-reinforcing trend:

Fintech has not exactly been helpful in slowing this trend down. Indeed, it’s quite the opposite.

As Kevin Moss and I explained in a prior Fintech Takes essay, the speed and occasional recklessness of fintech startups have placed an enormous amount of pressure on the credit bureaus to keep pace, and so far, the bureaus have been failing.

New loan product categories like BNPL and credit builders (my favorite!) have become enormously popular in a short amount of time, and the resulting consumer usage, combined with the bureaus’ scattershot approach to integrating and overseeing fintech data furnishers, has rendered consumers’ credit files significantly less reliable than they used to be.

Additionally, there’s now an entirely new source of programmatically available data (bank transaction data) for lenders to use either as a supplement or replacement to traditional bureau data. This data is rapidly becoming FCRA compliant, with Plaid being the latest data aggregator to take on the mantle of a consumer reporting agency (CRA).

(Editor’s note – FICO attempted to get ahead of the open banking trend by launching an off-shoot version of its score, UltraFICO, which incorporated consumer-permissioned bank transaction data with Experian and Finicity in 2018. However, it has not seen any meaningful traction in the market, as far as I am aware.)

If you’re a large consumer lender, are you going to wait five years for FICO to attempt to solve for these fintech headaches and opportunities (I stress the word attempt because there are some problems like credit builders that may not have an easy solution) in their next scoring model, or are you going to ask your data science team to do so within your own custom model instead?

You’re probably picking Door B.

And if you’re FICO, and roughly half of your revenue and most of your profit is generated by the FICO Score, how do you respond to your customers becoming increasingly less reliant on your core product?

You raise your price!

Here’s Marc Rubinstein again:

In order to offset headwinds, Fair Isaac has been pushing up prices. This began in 2018 with a 25%+ hike which was followed through in 2019 with the same. In early 2020, the Department of Justice opened an antitrust investigation but nothing came of it; the file was closed by year end. Since then, the company has continued to raise prices as part of what it calls a “special pricing” strategy. Having barely raised prices at all for 25 years prior to 2018, management believes there is a big gap between its scoring product’s value and the revenue it captures. In particular, the cost of a mortgage score is between $2 and $8, a tiny part of the $12,000 that makes up a mortgage’s closing costs. In other verticals, pricing is even lower, at 10-15 cents in cards and 30-40 cents in auto loans. Fair Isaac’s special price increases add $40 million to $60 million of incremental revenue per year and come with 95%+ margins.

Here’s the key part of that quote – “Having barely raised prices at all for 25 years prior to 2018, management believes there is a big gap between its scoring product’s value and the revenue it captures.”

That would absolutely be true if FICO’s customers had been diligently migrating to each new scoring model that the company had released in those 25 years, but that’s not the case! Most are using a score that was released in 2009! The value-revenue gap isn’t actually that big!

#2: The FICO Score as a Securitization Tool

At this point, you may be asking yourself, “Why are lenders buying the older versions of the FICO Score at all? What do they use it for?”

That’s a great question!

Lots of lenders still use it as an input into their custom scoring models or (in the case of smaller lenders) as their scoring model full stop. Again, the FICO Score is a very robust analytic tool.

However, there are a few other reasons which are worth getting into.

The most important one of these reasons is the secondary market.

As FICO discovered in the 1990s, providing an objective standard for investors in the secondary market to use in evaluating different loan investment products (whole loans, securities, servicing rights, asset-based lending facilities, etc.) is an enormously valuable proposition and an effective hedge against competition on the origination side of the business.

Even if a lender builds their own custom scoring model or chooses to use a general-purpose model from a competitor, they may still need to buy yours if the secondary market investors that they want to sell their loans to require it.

In the case of the U.S. consumer mortgage market, the largest and most liquid secondary lending market in the world, it became a guarantee when, in 1995, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac began requiring lenders to buy a FICO Score in order to sell them their conforming loans.

That requirement has stayed on the books for the last 30 years.

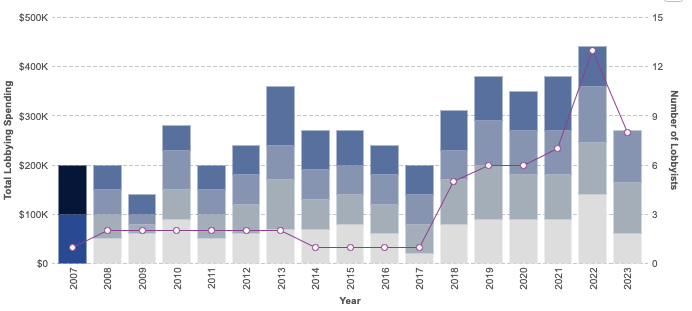

However, it is finally set to change, thanks, in part, to VantageScore spending approximately $4.5 million since its inception to lobby the federal government:

There are two big changes that the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), the regulator of Fannie and Freddie, is making (which will be slowly phased in over the next couple of years):

- Instead of requiring mortgage lenders to pull the Classic FICO Score, the FHFA will require lenders to pull the newest versions of both the Vantage Score (Vantage 4.0) and FICO Score (FICO 10 T, which is a more robust version of FICO 10) for each single-family mortgage loan they want to sell to Fannie or Freddie. These new scoring models vastly outperform the Classic FICO (not a shock) and take into consideration new repayment data (rent, utilities, telco), which may help additional consumers qualify for loans.

- Instead of requiring mortgage lenders to pull credit reports and calculate scores from all three credit bureaus for each conforming loan, the FHFA will require lenders to do only two. This change from a “tri-merge” model to a “bi-merge” model is being done to encourage competition between the bureaus and will obviously reduce the overall revenue pool for both the bureaus and FICO by a third.

The impact of the transition from the tri-merge model to the bi-merge model is fairly obvious and bad for both FICO and the credit bureaus (although the credit bureaus, which spent all that money lobbying the FHFA, are especially pissed).

The impact of requiring both FICO 10 T and Vantage 4.0 is less clear, but the fear for FICO is that it will weaken the company’s hold on non-mortgage loan securitization markets where only one score is required.

Additionally, beyond the securitization aspect of the switch to the new scores, on the origination side, borrowers, brokers, and loan officers are going to see both scores side by side, juxtaposed, on every loan for the first time. The consequences of this are unclear at this point, but it is interesting to contemplate as there are no other cases where a borrower is seeing multiple scores on the same loan and the impact of various score cutoffs on interest rates.

#3: The FICO Score as an Adverse Action Shield

Another non-analytic reason why lenders have traditionally valued the FICO Score is that it provides a very useful method for complying with adverse action notice requirements.

Adverse action notices (AANs) are explanations that lenders are required to give to consumers if they are denied for credit or given less favorable terms on a credit offer. AANs are mandated by both FCRA and ECOA. Their purpose is to both discourage discriminatory lending and to help consumers learn how to improve their creditworthiness.

AANs are very annoying to lenders because, among other things, they demand a straightforward answer to a complex question – why was this consumer declined for a loan?

That’s not easy to answer! Usually, it’s not just one thing. Usually, it’s a combination of interdependent factors that are very difficult to untangle and explain, especially if that explanation needs to make sense to a consumer who likely lacks a deep knowledge of how credit risk management works.

After the FICO Score was introduced in 1989, lenders saw an opportunity to leverage the structured nature of the scorecard to make compliance with adverse action requirements much easier. The scorecard was able to generate “reason codes” – the top factors (too many inquiries last 12 months, number of established accounts, etc.) that led to the declination.

This solution wasn’t, perhaps, perfectly aligned with the original intent of FCRA and ECOA, but for decades it was generally considered sufficient by regulators.

Until recently!

In September of last year, the CFPB released updated guidance for how lenders should approach complying with adverse action requirements. The guidance emphasized that AANs must be specific, especially when lenders may be relying on their own custom credit scoring models rather than generalized industry models like FICO:

Specificity is particularly important when creditors utilize complex algorithms. Consumers may not anticipate that certain data gathered outside of their application or credit file and fed into an algorithmic decision-making model may be a principal reason in a credit decision, particularly if the data are not intuitively related to their finances or financial capacity.

I wrote a lot more about adverse action and the CFPB’s guidance in this essay if you’re curious to learn more, but the bottom line is that lenders have, for decades, been getting away with using complex, homegrown analytic models to make credit decisions and then using the simplistic, high-level reason codes generated by old versions of the FICO Score to comply with adverse action requirements.

The CFPB is now telling lenders to knock it off, which will, if this new AAN guidance remains in effect, further degrade the value of general-purpose credit scores like FICO.

#4: The FICO Score as a Consumer Education and Planning Tool

As I have written about many times over the years, creditworthiness is one of the most confusing and frustrating financial topics that consumers wrestle with on a regular basis.

How do I establish my credit history if I’ve never had credit before? Why does shopping around for loans or paying off loans sometimes hurt my ability to get credit? Will I be approved for this loan, and if so, at what price?

These are very fair questions! Credit provides a critical function in consumers’ lives. They need at least a reasonable level of certainty around what they qualify for in order to plan out their futures and take advantage of time-sensitive opportunities.

The FICO Score has traditionally played a vital role in educating consumers on these questions and giving them a a fairly accurate understanding of what they might, at any moment, be qualified for.

FICO has been reasonably successful at defending this role for the FICO Score, even as VantageScore has worked, for years, to gain a foothold in the B2C credit monitoring space.

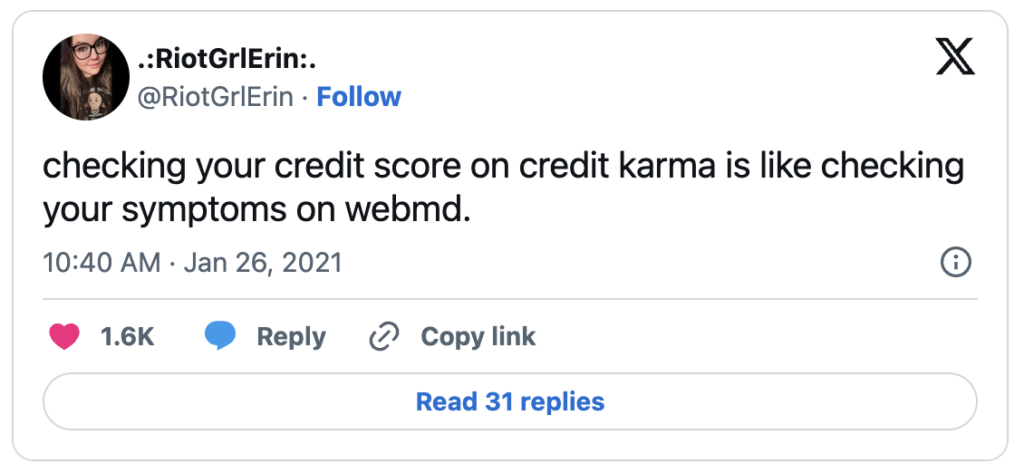

You might remember a few years ago when consumers got mad at Credit Karma because the free scores they were getting from the service (Vantage 3.0) weren’t the same as the scores that most lenders were using (FICO 8):

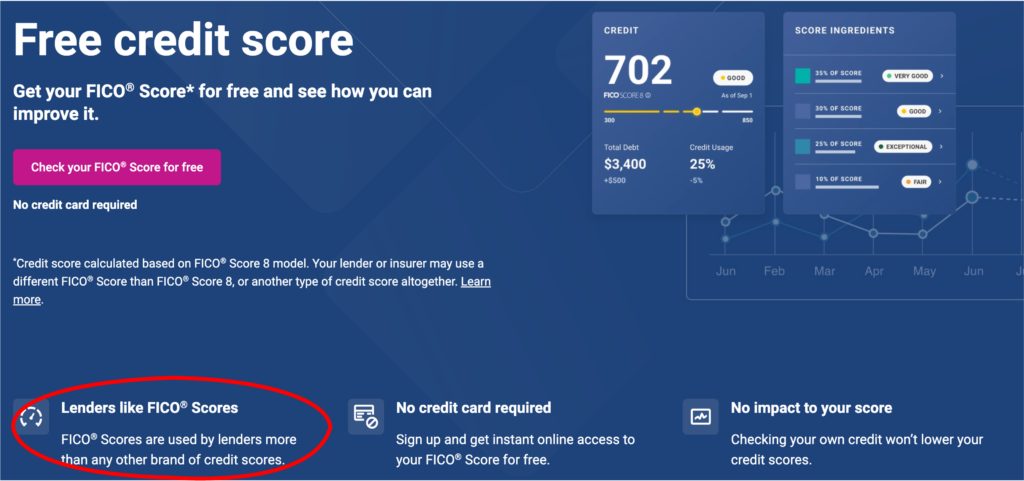

This argument – that the score consumers should look at should be the same one that lenders use to make decisions – was so persuasive that Experian, one of the three owners of VantageScore but also Credit Karma’s largest and most serious competitor, chose to offer its B2C users the FICO Score rather than the Vantage Score, a differentiator it prominently markets on its website:

The challenge for FICO, on the consumer front, is that the more disconnected the FICO Score becomes from the actual credit decisioning processes inside of large lenders (which are governed by the lenders’ custom models) and the more chaos fintech innovations (open banking, BNPL, credit builders) introduce into the market, the less utility the FICO Score will have a financial health touchstone for consumers.

For example, imagine that you’re a 20-year-old who has never had a credit card or an installment loan before. To date, you’ve mostly used BNPL to finance specific purchases, but you also recently started using the Chime credit builder card in order to build up your credit score faster because you are planning to buy a car next year.

Fast forward one year – you walk into a car dealership, pick out the car you want, and apply for a loan in the finance guy’s office. You are extremely confident because Experian is telling you that your FICO Score is 685. However, your confidence turns to befuddlement and anger when the finance guy informs you that you don’t qualify for any loan because, unbeknownst to you, every lender that sees your credit report is screening out or penalizing you for that Chime credit builder tradeline and none of the BNPL loans that you paid off were being reported to the bureaus.

This isn’t theoretical. This is happening today. And it’s likely to get worse, not better, which isn’t the fault of FICO, per se, but nevertheless, it is a significant threat to the FICO Score’s longstanding role as a consumer education and planning tool.

The End is Always Surprising

Even though it was expensive and annoying, I did end up deciding to fix the roof at my old house. But honestly? If I hadn’t, I’m sure the house probably would be just fine today and would stay that way for a long long time.

The Lindy Effect is subtle and powerful.

In the case of the FICO Score, the value that it provides as an industry standard is, despite my best efforts in the preceding paragraphs, difficult to fully explain. I’m not even sure that lenders consciously appreciate all of the benefits that the FICO Score provides.

One small example – FICO always takes the blame. Whether it’s consumer advocates and policymakers arguing that the U.S. credit system is inherently unfair or an individual consumer complaining about being declined for a loan, FICO quietly shoulders a lot of the criticism that should probably be falling on others.

Giving that up is hard. Replacing it is even harder.

It’s possible, of course, and (as we’ve covered) there have never been more reasons to believe that it might happen than there are today. But it would still be a surprise if something as durable as the FICO Score finally fell down. It always is.