17 August 2022 | FinTech

Fintech is Breaking the Credit Bureaus

By Alex Johnson

Editor’s note – Today’s essay was co-authored with Kevin Moss. Kevin is the former Chief Risk Officer for SoFi, a former Board Member at Varo Money and Snap Financial and the former Risk Leader for the Consumer Lending Group at Wells Fargo. I could go on and on, but suffice it to say that Kevin has forgotten more about lending and credit risk management than most of us will ever know. He is currently an advisor to more than a dozen startups in the U.S., Canada and the U.K. and he graciously agreed to collaborate with me on a topic that we are both passionate about – the impact of fintech innovation on the U.S. credit bureaus.

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills.”

– Ernest Hemingway

In the middle part of the last decade, consumers’ use of unsecured personal loans surged:

The number of people taking out unsecured loans jumped close to 30 percent in recent years, to 13.72 million in 2015 from 10.57 million in 2013, according to the latest data available from TransUnion.

Another 24 million Americans are likely to take out a personal loan this year alone, according to a separate report by Bankrate.

This sudden (and unexpected) growth in unsecured personal loans was due mainly to the emergence of several very successful fintech companies:

A slew of online lenders, like Lending Club and Prosper, have emerged in recent years to offer these types of loans as the alternative, particularly for millennials that may want to consolidate their debt but don’t have the home equity for a secured loan to do it.

The primary benefit of these loans for consumers was the ability to refinance their existing debts (credit card debt, primarily) at a lower interest rate. This wasn’t a new idea – consumers had been using installment loans to refinance credit card debt for decades – but Prosper and Lending Club and other online lenders made the process of acquiring these loans significantly less burdensome (5 minutes online rather than hours in a branch), leading to an increase in the number of consumers with credit card debt choosing to go down this route.

A second benefit for consumers refinancing credit card debt with these unsecured personal loans was the lift many saw in their credit scores. By significantly reducing or eliminating their revolving debt from their credit reports (and replacing it with installment debt), these consumers improved on a key metric that credit scores weigh heavily – credit utilization – and subsequently saw significant positive boosts to their credit scores.

There was just one problem.

Those credit score increases weren’t indicative, in most cases, of lower credit risk. Fundamentally, we just exchanged one form of debt for another (cards vs. loan), and after paying off their credit cards, many of these consumers went right back and loaded their cards up with more revolving debt, and had a loan for a similar loan amount. Their behavior hadn’t fundamentally changed, and their improved credit scores were merely a mirage.

Why did this happen? How did fintech fool the FICO score?

Simple – the credit bureaus and FICO never anticipated, when they initially designed the way that credit data would be recorded and scores calculated, that consumers would have push-button access to unsecured personal loans that they could use to pay down credit card debt. They didn’t see that coming.

Now, to be fair, we can’t blame them for that. Predicting the future is hard! And FICO did adjust its algorithm (five years later) to account for this shift in consumers’ behavior with the release of FICO 10:

The changes will be extensive. About 40 million Americans are likely to see their credit scores drop by 20 points or more, and an equal number should go up by as much, according to Joanne Gaskin, vice president of scores and analytics at FICO, the company at the heart of the credit scoring system.

Every five years or so, FICO updates the way it determines credit scores. This time, the biggest change is in how it treats personal loans, Gaskin says.

Let’s say you pay off all your credit cards with a personal loan. Under the old system, your credit score might go up. But under the new approach, FICO will look back over a period of time — as far as two years — to see whether you’ve used the loan to reduce your high-interest credit card debt or whether you’re using plastic as much as before, running up new revolving balances and falling deeper into debt.

“What we find is that potentially that consumer’s credit file carries more risk than what was apparent,” Gaskin says.

What’s important to understand, though, is that this entire example – the emergence of online lenders offering unsecured personal loans for debt refinance, the impact on consumers’ credit scores, and the eventual course correction by FICO – was merely an amuse-bouche, a taste of what was to come.

After all, Lending Club and Prosper hadn’t pushed the envelope all that far. Yes, they had made acquiring unsecured personal loans a lot easier. That ease of access led to an increase in credit card debt refinance that temporarily warped some consumers’ credit scores. Still, the underlying financial product – the unsecured installment loan – remained the same as it always had been.

What would happen to the lending ecosystem, one wonders, if fintech made more fundamental alterations to the design of traditional lending products?

Well …

Fast forward to 2022, and we find two far more substantial and disruptive innovations in lending that fintech has introduced:

‘Pay-in-4’ Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL)

The way these products work is simple — consumers are presented with the option (typically at the point of sale) to split their payment into four installments. The first installment (25% of the total transaction) is paid at the time of the purchase, and the remaining three installments (of 25% each) are paid back in two-week increments (for a total loan term of six weeks).

The loan is offered at 0% interest and typically comes with no fees. The loans can be repaid via ACH, debit card, or (in some cases) credit cards, and if the loan isn’t repaid, access to loans from the BNPL provider in the future is often suspended.

Pay-in-4 BNPL loans are most commonly used for smaller dollar transactions (less than $250), and a majority of the volume for these loans is sourced from higher-margin, discretionary-spend categories like apparel, footwear, fitness, accessories, and beauty. The typical pay-in-4 customer is young and either non-prime or credit invisible. BNPL providers (Klarna, Affirm, Afterpay, etc.) have, for the most part, not reported these loans to the credit bureaus, but that is starting to change.

Credit Builder Cards

These cards, offered by fintech companies like Chime, Varo, and Tomo, are essentially secured credit cards.

The twist is that instead of requiring an upfront deposit, these products find other, more customer-friendly ways to offset the risk to the issuer.

Tomo has a 7-day payment cycle with automated repayment. Chime and Varo automatically set money aside from the customers’ checking accounts into separate secured accounts as they spend on the credit card, which functions as a type of escrow for the card’s balance and makes repayment at the month easy.

In practice, these cards virtually eliminate the possibility of missed payments. This is great for the issuers (low default rates) and is essential to delivering on their core value proposition – helping customers establish credit files and improve their credit scores.

OK, you may be saying, so far, this all sounds pretty good. What’s the problem?

To answer that, we must first explain how the credit bureaus capture and organize novel credit data.

Lots of Square Pegs and Round Holes

Editor’s note – we’re keeping it simple and sticking with a non-technical description of how this process works. If you want to dive into the rabbit hole and unpack the mysteries of Metro-2, let us know, and we’ll connect you with the right folks.

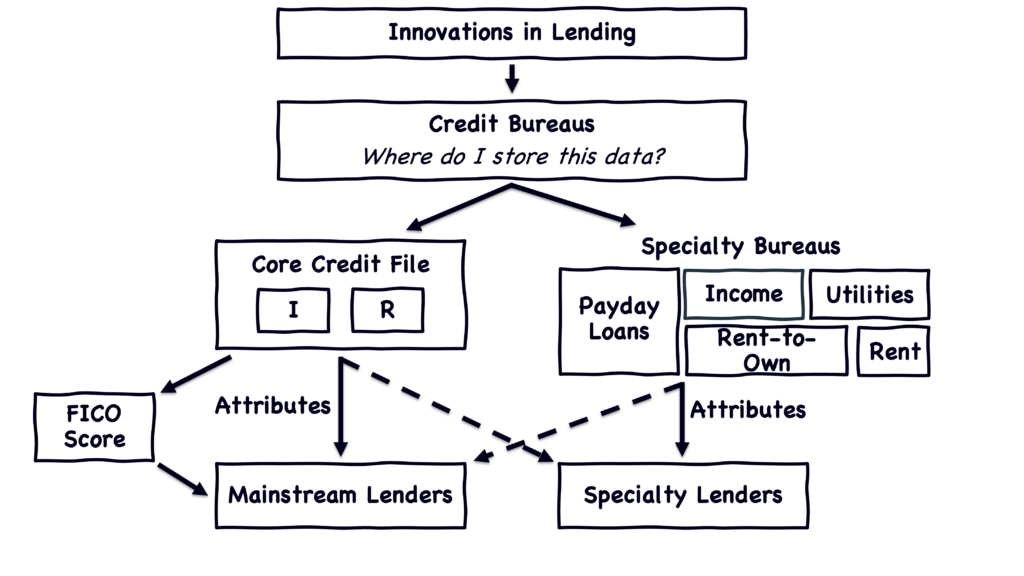

When the credit bureaus come across innovative data that could, theoretically, be used to help make an accurate assessment of a consumer’s probability of default on a credit obligation, they have two options for how they can capture that data and make it available to lenders.

- Add it to consumers’ core credit files. Within the credit file, there are two primary ways that the data can be categorized, based on the type of lending product that is generating the data – as a revolving loan tradeline (i.e., a credit card) or as an installment loan tradeline (i.e., any loan with a fixed term).

- Segment the data away from the core credit file and keep it in a separate database. This is an obviously appealing approach to dealing with data that is useful for making credit decisions but doesn’t quite fit into the revolving and installment product categories within the core credit file, such as income or rent payment data. It is also the approach that the credit bureaus have traditionally taken when they have acquired niche credit bureaus focused on subprime or specialty finance segments (Clarity, FactorTrust, etc.)

In both cases, the bureaus provide lenders with attributes that summarize the raw data, which the lenders then use in constructing proprietary scoring models and underwriting algorithms.

In theory, attributes from both core credit files and specialty bureaus can be used by any lender. However, in practice, mainstream lenders tend to make credit decisions exclusively using core credit files, and specialty lenders tend to exclusively use data from the specialty bureaus that provide coverage of their target customers (i.e., payday lenders using payday lending bureau data).

In the case of core credit files, FICO is constantly refining its scoring algorithm based on the data provided by the bureaus. It introduces new versions of the FICO Score (distributed through the credit bureaus) every five years or so. Lenders can adopt the new scores or (as is more common) adjust their custom models while continuing to use older versions of the score.

The whole process looks something like this:

So, returning to the question, why do fintech innovations like BNPL and credit builder cards present a challenge to the credit bureaus?

Well, where do you put them?

Where do you put BNPL pay-in-4? It’s an installment loan, but it also looks nothing like a traditional installment loan. 25% of the principal is repaid immediately. And there is no interest. And the loan amounts are tiny compared to even the smallest traditional unsecured installment loan. It also looks a little like a revolving line of credit – the BNPL providers usually underwrite each customer for a maximum loan amount that each individual BNPL transaction then eats into, kind of like a credit card – but it’s also clearly not a credit card.

Maybe you just throw up your hands and create a separate specialty bureau for BNPL?

There aren’t any obviously correct answers, and the way we know that is that the credit bureaus, who have been studying this problem extensively for the last few years, have opted for different answers.

Equifax is incorporating BNPL into the core credit file as a revolving loan tradeline, confident that the overall impact for most BNPL users will be positive:

“Equifax will be the first credit reporting agency to formalize a standard process for reporting BNPL tradelines for inclusion on traditional consumer credit reports,” said Mark Luber, Chief Product Officer for U.S. Information Solutions (USIS) at Equifax. “We are committed to helping people live their financial best, and recognize the role that BNPL services can play in helping people build stronger financial profiles.”

TransUnion disagrees and is taking a different approach, segmenting the BNPL tradelines away from the traditional installment and revolving loan tradelines, at least in the short term:

TransUnion is launching the capability to receive point-of-sale lender trades through the traditional credit reporting process, with specific Metro 2® reporting guidance that ensures FCRA compliance. The goal is to have a single standard for lenders to report data and accelerate adoption by lenders and scoring providers in the future. The information will be tagged and filtered into a new partitioned part of TransUnion’s core credit file.

Users of TransUnion credit data will be able to opt-in to receive these tradelines as part of their existing credit data delivery. Default credit report delivery, which feeds existing scoring models, will remain unaffected. Over time, as the industry works to enhance models with these data, it is expected that many lenders will choose to use the information in addition to their existing models to help expand their buy boxes – accelerating the consumer impact.

Long term, TransUnion plans on including point-of-sale data on the core credit file where it can maximize the number of credit decisions that it impacts. “The industry needs time to adjust, and each lender will adopt the point-of-sale tradelines and attributes at its own pace. Maximizing the financial inclusion impact requires broad usage of this valuable data in more credit decisions. Ultimately, given the prominence of FICO and VantageScore in the market, the biggest impact from the data will not be realized until the data migrates to the core file and these scores take into account consumers’ good behavior,” added Pagel.

Experian is doing something similar, based on the same concern that putting BNPL tradelines in the core credit file could hurt consumers:

reflecting BNPL information on credit reports as traditional loans or lines of credit can create negative impacts to consumer credit scores, even when BNPL products are used responsibly. This has, justifiably, prevented many BNPL providers from reporting BNPL payment information.

Experian will debut The Buy Now Pay Later Bureau™ later this spring. This first-of-its kind bureau will protect consumer credit scores from negative impact while driving more inclusive and responsible lending.

The Buy Now Pay Later Bureau will allow BNPL providers to furnish data on all types of point-of-sale products – enabling a comprehensive view of consumer payments, including the number of outstanding BNPL loans, total BNPL loan amounts and BNPL payment status. To protect consumer credit scores from immediate negative impact, detailed information related to each BNPL transaction will be stored separately from Experian’s core credit bureau data.

Of course, this segment-away-from-the-core-credit-file approach has its drawbacks.

Lenders don’t like buying multiple credit files or having to figure out how to incorporate additional credit attributes into their custom models. Particularly if they believe that the marginal value of doing so – identifying additional qualified credit customers – will be minimal. This is the problem with many of the specialty bureaus that currently exist – the only lenders that use them to make credit decisions are the ones that report to them. Because of this, they are mainly ineffective as on-ramps into the mainstream credit system for subprime and credit invisible consumers.

They also inhibit lenders’ ability to accurately determine an applicant’s ability to pay – if a consumer’s debt obligations are stored across the core credit file and multiple specialty bureaus, a lender evaluating that consumer has no easy way to assess their ability to pay.

Additionally, the fragmentation of this data and the lack of uniformity in how it’s handled across the bureaus make FICO’s job much harder. It needs to create a new version of its score that takes BNPL into consideration, and that score needs to work the same across all three bureaus, a task not aided by the bureaus each treating BNPL data differently.

And then there are the credit builder cards.

This is a popular product category in fintech. They give neobanks a way to strengthen their core value proposition (we help underserved consumers access the financial services they deserve) and collect higher interchange rates without taking any substantial credit risk. We expect to see many more such cards appear in the market over the next few years.

And that’s a problem for the credit bureaus.

Remember, the design of these products all but guarantees that customers are going to pay their balances off in full every time (Tomo recently reported that its default rate on its card is 0.11%). The data being furnished back to the credit bureaus is almost exclusively positive. It’s going right into the core credit file as revolving loan tradelines and, consequently, customers’ credit scores are jumping up.

The trouble is that this repayment data isn’t an accurate reflection of customers’ willingness to repay loans. The providers of credit builder cards aren’t taking actual credit risk, and, as such, the performance of their portfolios is, from an underwriting perspective, useless.

Put simply, the data generated by these products is polluting the credit bureaus and giving other lenders a distorted view of the credit quality of the consumers using them. And to top it all off, there is no easy way for lenders or FICO to correct for this distortion in their scoring models. The data looks just like regular revolving loan tradelines.

What To Do

Fintech is breaking the credit bureaus. And it will continue to do so.

The pace of innovation in lending, brought on by fintech, will continue to accelerate, and new, even more creative product categories will emerge and gain traction with consumers.

Product categories like income share agreements (ISAs), which help students finance above the government limit qualified education expenses with a private loan-like alternative for those that do not have a co-signer available to obtain a private loan. ISAs are not currently reported to the bureaus, as they do not neatly fit into the core credit file, but it’s not hard to imagine a world in which these products become popular enough that the bureaus have no choice but to figure it out.

The credit bureaus need to accept this. They need to become strong in the broken places. They need to create new tradeline types (credit builder trades, BNPL, ISAs, etc.) to address the financial innovation in fintech products, and these new tradelines types should all be integrated into the core credit file so that any consumer who borrows money will be getting credit for their positive and negative payment and usage experiences, with all lenders. And so lenders (and FICO) can easily access the granular data they need to build effective scoring models and underwriting algorithms.

We recognize that this isn’t a small ask or an easy task.

The technological and operational lift necessary to update the core credit file and the surrounding furnishment and dispute management infrastructure is significant. The challenge of doing so in a coordinated fashion across all three bureaus and FICO is daunting and somewhat antithetical to the desire of all four companies to maximize their competitive differentiation.

We also recognize that this will take years to accomplish. Even if these new tradelines are incorporated into the core credit file, we will still need to backfill tons of data into those new tradeline types. We will need to wait years for the performance data on those loans to catch up so that credit risk professionals and data scientists can start to test and find ways to incorporate these tradelines into their models. And we will need to wait even longer for those new models to be integrated into production lending environments, tested as challengers, and (if they prove superior) adopted as the new champions.

It will take years, but if the credit bureaus don’t act urgently, they risk an even worse fate.

Fintech lenders, banks, and regulators are becoming increasingly comfortable with credit decisioning based on deposit transaction data, enabled by data aggregators like Plaid, Finicity, and MX. As open banking continues to become the default assumption for financial data in the U.S. (especially post-1033), we expect to see greater use of deposit transaction data within lending, not just for credit cards but for all consumer lending products, which has the potential (in the long term) to upend the established credit infrastructure in the U.S completely.

Fintech is breaking the credit bureaus. And if they will not break, it may kill them.