29 December 2023 | FinTech

A Call for Craftsmanship

By Alex Johnson

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become less and less of a fan of New Year’s resolutions.

This is likely due to the fact that I, like most people, struggle at self-improvement, and making a long and ambitious list of specific self-improvement goals for the coming year has always been a surefire way to bum myself out by March or April.

So, instead, I’ve adopted the practice (first suggested to me by my mom) of picking a single word to focus on for the coming year, a word that can help me shape my thinking and actions for the next 12 months without the pressure and specificity of a list of resolutions.

My word for 2024 is craftsmanship.

I wanted to use today’s essay to explain why I think this word is so important, for me and Fintech Takes, for the financial services industry, and for the economy as a whole.

It’ll be easiest to explain if I start at a macro level and work down from there.

Why Craftsmanship Will Become More Valuable

The last 200 years of economic growth have been driven, in large part, through standardization.

To use just one example, in 1855, the British Royal Navy urgently needed 120 gunboats for its war in Crimea. Admiral Charles Napier demanded that these gunboats be manufactured within 90 days, which was a reasonable request for the British shipwrights responsible for the boats, but an absolutely crazy request for the British engineers responsible for the boat engines.

However, a marine engineer named John Penn was able to solve the problem by disassembling two of the required engines and shipping the individual parts to the best machine shops in the country, with orders to reproduce them ninety times. The finished parts were then shipped back and reassembled by Penn into the final engines in less than 90 days, a feat that astonished and delighted Admiral Napier.

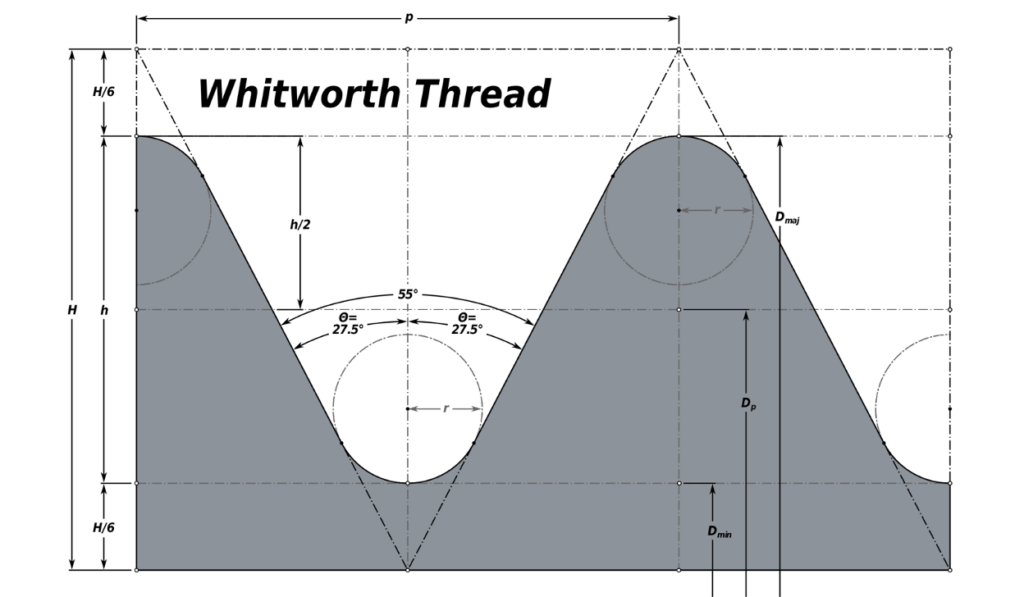

Penn’s accomplishment – the first time mass production techniques were applied in marine engineering – was only possible because, 14 years earlier, a different engineer named Joseph Whitworth had devised the British Standard Whitworth, the world’s first national screw thread standard, which made the mass production of individual parts and centralized assembly of machines from those parts feasible.

Fast forward through 180 years of technological progress and increased standardization, and you get the modern global economy – a finely-tuned engine of efficient mass production powered by mechanical and digital automation, a complex web of supply chains, and a robust global trade infrastructure.

As Adam Davidson, co-founder of NPR’s Planet Money podcast, observed in his book The Passion Economy, this transformation has profoundly changed the role of human labor in the economy:

Computers and the machines they run are much better at performing routine tasks than humans are. Today, robots make the robots that make ball bearings. At the same time, increasing global trade means that those tasks that do require human labor are increasingly often performed in low-wage countries. This is not a one-time transition. Countless hundreds of thousands of consultants, engineers, and business strategists are constantly studying technology and global markets to figure out how to make more things with fewer people.

And, of course, the technological forces driving this transformation aren’t stopping. Davidson’s book (which I highly recommend reading) was published in 2020. Since then, we’ve seen the emergence of an entirely new field of technology – large language models (LLMs) – which have already demonstrated enormous potential to minimize the role of humans in economic output even further. As Frank Rotman, Chief Investment Officer at QED Investors, helpfully laid out in a brilliant Twitter thread, LLMs (or silicon-based learning machines as he delightfully refers to them as) have the potential to do for tasks requiring human judgment, the same thing that robots have done for tasks requiring human physical labor:

Example – Customer service

Carbon-based learning machine [AKA a human]:

Interacts with customer to authenticate who they are (2 min), asks questions to understand their problem (5 min), pulls up policy docs and explains the proposed resolution to the customer (10 min), executes solution and documents system (3 min).

Total compute time 20 minutes at a loaded cost of $1 a minute = $20.

Loaded costs are inclusive of compute costs, benefits, management overhead, real estate, etc.

Accuracy: High for simple questions with an increasing error rate as customer requests become more complex.

Silicon-based learning machine:

Interacts with customer to authenticate who they are, asks questions to understand their problem, pulls up policy docs and explains the proposed resolution to the customer, executes solution and documents system.

Total compute cost of $0.50.

Accuracy: Near 100%

And silicon-based learning machines won’t just confine themselves to customer service jobs. They’ll be used everywhere human judgment is currently required, even in fields that have traditionally been seen as highly creative or artistic, including coding, video production, and music.

So, what’s the endgame of this economic transformation?

I would guess that it will be a more extreme version of what we have today – abundance. A world in which the technology exists to manufacture and distribute virtually any product or service quickly and at extremely low costs.

This tees up a much more interesting question – in a world of extreme abundance, what will humans choose to value?

In his book, Adam Davidson makes the case that we will increasingly value ‘unique’ products and services created by passionate and entrepreneurial individuals and companies. He calls this the passion economy:

The same forces – technology and trade – that destroyed the widget economy have given birth to what I call the passion economy. The internet allows people who want to sell a unique product or service to find customers all over the world. Automation makes it possible for people to manufacture their unique products without needing to build a factory first. Advances in trade mean that those unique products can be delivered to the people who most value them, wherever they happen to be.

I think Davidson is correct in his analysis, and if he is, it will represent a significant departure from the last couple of centuries of economic evolution, which were defined by the struggle the embrace standardization and get as far away from ‘unique’ products and services as possible.

But what exactly is a ‘unique’ product or service in this context? What does it look like?

In my opinion, a unique product or service – one that consumers would choose to value and pay highly for in a world overflowing with cheap, replacement-level substitutes – has two characteristics:

- An opinionated and unconventional design.

- Labor-intensive production and/or delivery.

Put simply, in the future, we will value things that are unusual and things that are scarce.

The reason I believe this is that many of the most successful and distinguished entrepreneurs and artists of the last 50 years have, either intentionally or instinctively, tapped into this formula.

Why Christopher Nolan and Tom Cruise Are My Two Favorite People Working in Hollywood

Christopher Nolan and Tom Cruise are very different. One is a director. One is an actor. One makes dense, cerebral films. One makes films that are extraordinarily straightforward.

Something they have in common, however, is an extreme distaste for computer-generated graphics (CGI).

Here’s Nolan explaining why he’ll use CGI to touch up scenes shot with a camera (a film camera, BTW, Nolan won’t use digital cameras) but won’t use it to create entire shots from scratch:

The thing with computer-generated imagery is that it’s an incredibly powerful tool for making better visual effects. But I believe in an absolute difference between animation and photography. However sophisticated your computer-generated imagery is, if it’s been created from no physical elements and you haven’t shot anything, it’s going to feel like animation. There are usually two different goals in a visual effects movie. One is to fool the audience into seeing something seamless, and that’s how I try to use it. The other is to impress the audience with the amount of money spent on the spectacle of the visual effect, and that, I have no interest in. We try to enhance our stunt work and floor effects with extraordinary CGI tools like wire and rig removals. If you put a lot of time and effort into matching your original film elements, the kind of enhancements you can put into the frames can really trick the eye, offering results far beyond what was possible 20 years ago. The problem for me is if you don’t first shoot something with the camera on which to base the shot, the visual effect is going to stick out if the film you’re making has a realistic style or patina. I prefer films that feel more like real life, so any CGI has to be very carefully handled to fit into that.

The big scene in Nolan’s latest movie – Oppenheimer, which I saw in the theater – was the Trinity test, the first-ever detonation of a nuclear bomb. As you might guess, the explosion depicted on screen was real. The film’s visual effects supervisor blew up dozens of drums of fuel, filmed from multiple angles simultaneously, and then slowed the explosion down in post-production in order to make it appear larger and more powerful. This approach allowed the film’s cast to actually experience the explosion on set in New Mexico, creating a much more realistic environment for them to perform in.

The other big-budget movie that I saw in the theater this year was Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning Part One. Not quite the same prestige fare as Oppenheimer, but hella entertaining. The big moment of the film is the scene in which Tom Cruise’s character rides a motorcycle off of a cliff and into a base jump. Cruise, who is 61 years old, spent months training for this one shot, doing 500 hours of skydiving training and 13,000 motorbike jumps (if you have time, watch this behind-the-scenes video of the making of this shot). And on the day that they filmed it, he did it six times, even though the first time gave them enough shots to work with.

This is not a one-off for Cruise. If you’ve been sampling his late-career filmography, you’ll know that he has come to specialize in these high-risk action movie stunts, which are performed almost entirely with practical effects (and just a little bit of CGI to remove wires and other safety aids). Here’s how he justifies his insane risk-taking:

It communicates to an audience when it’s real. It’s different, there’s real stakes and … and there’s performance. Part of that is – they can put cameras in the places with me, that you might not think of when you’re doing CGI, or, it just has a different emotional vibe … it has a different emotion for the audience, a different quality. And I grew up watching practical action.

Why do Nolan and Cruise feel compelled to eschew CGI when, commercially speaking, they’d likely be able to get away with it (and save themselves and their coworkers a lot of hassle) if they wanted to?

Why do they choose to do the hard thing rather than the easy thing?

I think the answer is craftsmanship. They care deeply about their craft. They want to do everything the right way because doing it any other way just wouldn’t feel right.

That’s their motivation, but it’s also smart business. As audiences and critics have begun to tire of Marvel Studio’s we’ll-just-CGI-everything approach to filmmaking (if you saw the latest Ant-Man movie, you know what I’m talking about), movies like Oppenheimer and Mission: Impossible have started to stand out specifically because the audience knows, going in, how much genuine craftsmanship went into their creation.

And it’s not just movies where this shift is starting to play out. It’s everywhere you look.

Here are a few other examples that have been top-of-mind for me:

- Steve Jobs. The news that came out earlier this year that Apple won’t replace its Head of Industrial Design (a role filled, for many years, by Jony Ive) but will instead have its designers report to the Chief Operating Officer underlines just how much the company has changed since the death of Steve Jobs. Jobs, who was famously obsessed with craftsmanship, once said, “When you’re a carpenter making a beautiful chest of drawers, you’re not going to use a piece of plywood on the back, even though it faces the wall and nobody will ever see it. You’ll know it’s there, so you’re going to use a beautiful piece of wood on the back. For you to sleep well at night, the aesthetic, the quality, has to be carried all the way through.”

- Robert Caro. The most influential biographer of the last century has spent almost his entire career obsessively working on the definitive biography of one man – Lyndon Johnson. Here’s how comedian Conan O’Brien (the world’s biggest Robert Caro fan) describes him, “This man … has dedicated his whole life essentially to writing about … one man and doing it his way, without compromise, very quietly, in a very small office … and he has this dedication to what he’s doing that almost feels like it’s akin to Egyptians building a pyramid.”

- Joe Brumm. The creator of the greatest kids television show ever – Bluey. In trying to create a kids show that parents would enjoy as well, Brumm insisted on writing every episode himself rather than hiring a team of writers because, in his experience, kids television writers tend to be lazy and formulaic. He also insisted that the show spend money on the aesthetics, saying, “We really tried to get it to look beautiful and to sound beautiful. It should have its own score and its own visual style and really not just [be about] trying to knock it out for cheap.”

- Taylor Swift. Having attended an Eras Tour concert personally, I can say that I’ve never seen more care and craftswomanship put into a live entertainment experience. Three hours. 45 songs. Simply on a physical stamina level, it was one of the most amazing athletic achievements I’ve ever seen. And when you consider that concerts, historically, were never a big moneymaker in the music business and that Swift could certainly have gotten away with half-assing it (given the built-in passion of her fanbase), the Eras Tour turning out to be this Earth-shaking juggernaut is a massive surprise.

- Paul Graham. In his famous essay Do Things That Don’t Scale, the Y Combinator co-founder extolls the virtues of startup founders spending an absurd amount of time doing the obsessive, detail-oriented, labor-intensive work to get their flywheels spinning. Graham ends the essay by pointing out the long-term benefits to companies that cultivate this obsessive craftsmanship and care early on, “The unscalable things you have to do to get started are not merely a necessary evil, but change the company permanently for the better. If you have to be aggressive about user acquisition when you’re small, you’ll probably still be aggressive when you’re big. If you have to manufacture your own hardware, or use your software on users’s behalf, you’ll learn things you couldn’t have learned otherwise. And most importantly, if you have to work hard to delight users when you only have a handful of them, you’ll keep doing it when you have a lot.”

All of these individuals succeeded in an era of unprecedented efficiency and standardization, despite their insistence on doing their work in some of the most unconventional and inefficient ways possible.

I don’t think that’s an accident.

In fact, I think they are early examples of a template for success that will become much more important, across all industries, in the future.

And as I look into 2024 (and beyond), I’m very curious to see how that template might be applied in financial services.

Financial Services Needs More Craftsmanship

The biggest change in financial services over the last couple of decades is the dramatic reduction in the cost of manufacturing and distributing financial products.

While BaaS is a bit of a nightmare right now, it has, overall, proven to be a very cost-effective model for launching new financial services brands and enabling embedded finance within non-finance brands. Things have gotten even easier in the last five years thanks to the proliferation of fintech infrastructure, designed to make it faster and less operationally intensive for new fintech companies to get up and running.

And, of course, distribution costs have plummeted thanks to the internet replacing branches as the primary vehicle for getting financial products into consumers’ hands.

The challenge, however, is that we are now awash in a sea of sameness. It’s simply too easy today to quickly copy what everyone else is doing, which has led to a mass convergence in product roadmaps across the industry.

So, where are there opportunities for craftsmanship in financial services?

It’s not an easy question to answer. Financial services is heavily regulated. The government doesn’t want banks creating ‘unique’ products. And given that money is essentially just 1s and 0s, there aren’t a lot of tangible avenues for directly conveying craftsmanship to customers the way that there are with an industry like consumer electronics.

Having said that, I do have a few ideas:

- More opinionated products. It’s strange to me, in an age of infinite shelf space, how monolithic financial products still are. Offering generic, one-size-fits-all deposit, lending, and investment products made sense in the era of branch-based distribution (you needed standard products for your bank tellers to sell), but it makes very little sense today. As I wrote about a while back, I think checking accounts are an excellent place for banks to start experimenting with more opinionated and narrowly tailored product designs.

- Customer service. As Frank Rotman outlined in the Twitter thread shared earlier in this essay, silicon-based learning machines will likely gobble up a majority of the low-value customer service interactions currently being handled by humans. This is a good thing (those human interactions aren’t helping companies differentiate themselves today), but it also leads to a question – once AI-powered agents are handling virtually all routine customer service tasks, will customers place a premium on interactions with real humans? And, if so, which types of human-powered interactions will provide customers with the most value? I think we will see banks and fintech companies experiment extensively in this area over the next ten years (particularly for high-net-worth consumers and certain B2B segments).

- Partnerships. Most “partnerships” in financial services are either vague promises to possibly work together in the future or a pleasant-sounding euphemism for the relationship between a vendor and its customer. Very few non-vendor partnerships have any real work, commitment, or investment behind them, but that’s exactly what makes the ones that do so uniquely valuable. Embedded finance, where the right to win must be continually earned, is where I think we will see the biggest positive impact of well-crafted partnerships over the next decade.

- Culture. Hamish McKenzie, co-founder of Substack, recently published a great essay on the distinction between content and culture in the age of AI. McKenzie’s argument is that as the cost of creating content continues to fall thanks to LLMs, the importance of genuine cultural connection (fostered through high-quality content) will rise correspondingly. I’ve long thought that Cash App has the most intuitive understanding of the importance of culture of any financial services company. I wonder if we will see other banks or fintech companies make culture, content, or community a priority in the years to come.

None of these are a sure thing, of course. Just educated guesswork.

What I am sure about is that craftsmanship will be a defining characteristic of the work that I do through Fintech Takes in 2024.

Craftsmanship and Fintech Takes

I am convinced that obsessive craftsmanship will be the template for economic success in the world of extreme abundance that we have built (and are continuing to build).

But even if I wasn’t convinced, I would still commit myself to this template for the coming year (and beyond).

You know why?

Because it fucking rules to build something that is the best possible version of itself. The best essay. The best podcast. The best event. The best slide deck. The best email. It’s really satisfying to add to the sum total of utility, beauty, humor, and kindness in the universe, just because I can.

To quote Jeff Bebe, it’s not about money and popularity (although some money would be nice).

So, in keeping with this commitment, here are a few small ways that I am planning to bring a greater level of craftsmanship to Fintech Takes in 2024:

- Typos. We have a philosophy of ‘publish over perfection’ here at Workweek, so a few typos are to be expected. Having said that, I am going to do my absolute best to limit them in my work over the coming year.

- Strong opinions, weakly held. It’s difficult to find the balance between publishing strong opinions without being mean or stubborn in the face of conflicting facts or logical arguments. But I try to find this balance in everything I write and say and will continue to strive for this equilibrium in 2024.

- Relationships. My theory is that most of the best podcasts out there are just recordings of great conversations between interesting people who like each other. I worked hard this year to lay the foundation for capturing some of these conversations in my podcast by building strong, trusted relationships with people in this industry whom I admire (Jason Mikula, Kiah Haslett, Simon Taylor, and tons of special guests). I plan to build on this foundation over the next 12 months.

- Small is the new big. As we roll out more events and community products through Fintech Takes in 2024, this will be my guiding philosophy. I will focus on curating small group interactions and engineering as much serendipity through those interactions as possible.

- Curiosity. Curiosity doesn’t scale very well, which makes it extremely difficult to chase my curiosity as much as I would like to on a regular basis and still publish two newsletters and a podcast every week. However, while curiosity doesn’t scale, it does compound. Indulging my curiosity helps me expand my knowledge and network and, ultimately, deliver more valuable insights to the Fintech Takes’ audience. In 2024, I will find more ways to do this without destroying my productivity.

See y’all next year!