04 November 2023 | Healthcare

Streaming a Cure: How Subscription Models May Improve Healthcare Access

By workweek

There’s a cure for Hepatitis C, yet it remains widely prevalent in society. I attended a captivating grand rounds two weeks ago by gastroenterologist Julius M. Wilder, MD, PhD. His exploration into the economic factors and social determinants surrounding Hepatitis C was so enlightening that I felt compelled to highlight some of his insights in this newsletter.

In this article, I’ll give background on Hepatitis C, discuss the Netflix Model for its treatment, and expand on how it may be applied to diseases like diabetes and obesity.

The Deets on Hepatitis C

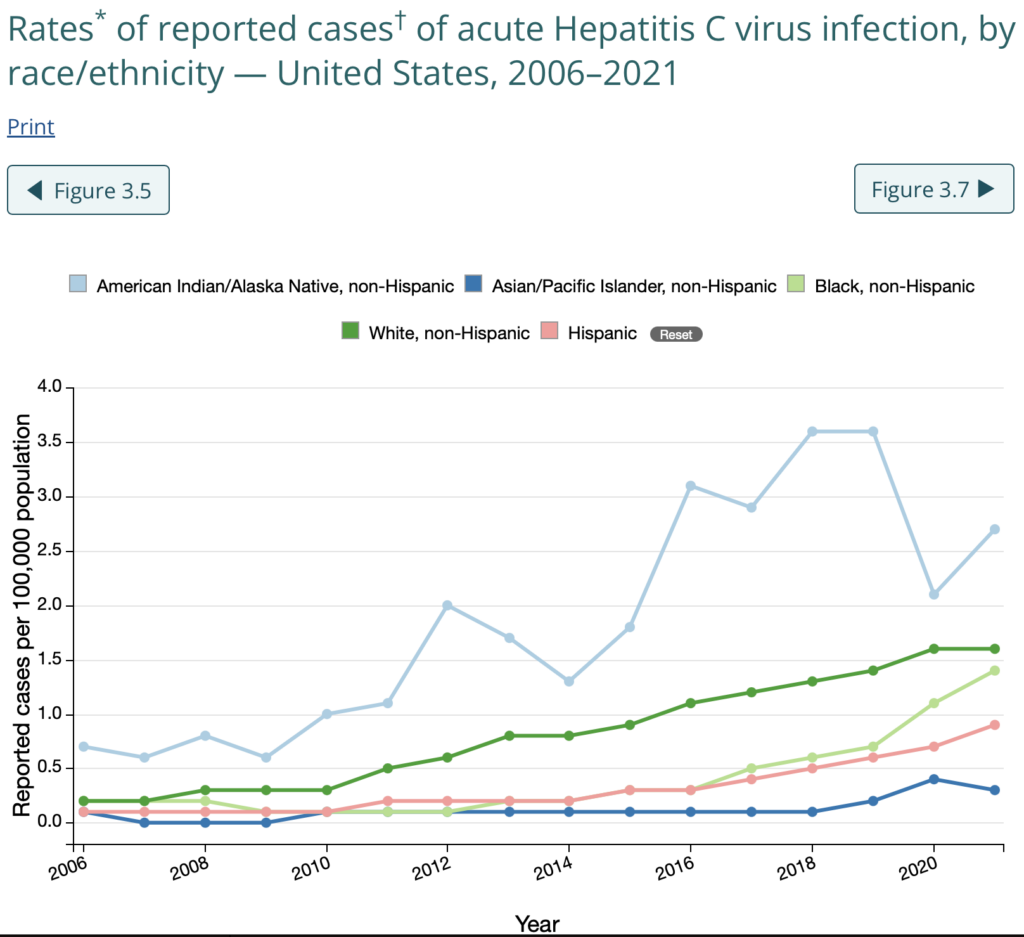

The incidence of acute Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) infection has more than doubled since 2014, and it does not treat all races/ethnicities equally. Acute HCV infection rates, for example, are 9x higher among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native persons compared to non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islanders. At a more granular level, specifically in the incarcerated population, the prevalence of HCV infection is nearly double in Black men than in other races and ethnicities.

Disparities also exist for death rates from HCV, with non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native and non-Hispanic Black persons having the highest death rates, around 10 per 100,000 and 5 per 100,000 with HCV, respectively. The ripple effects of structural racism, including housing policies, redlining, over-policing, healthcare access, and lack of Indian Health Service funding, all play a role in the above HCV disparities.

Here’s the most shocking part about everything: there’s a cure for HCV.

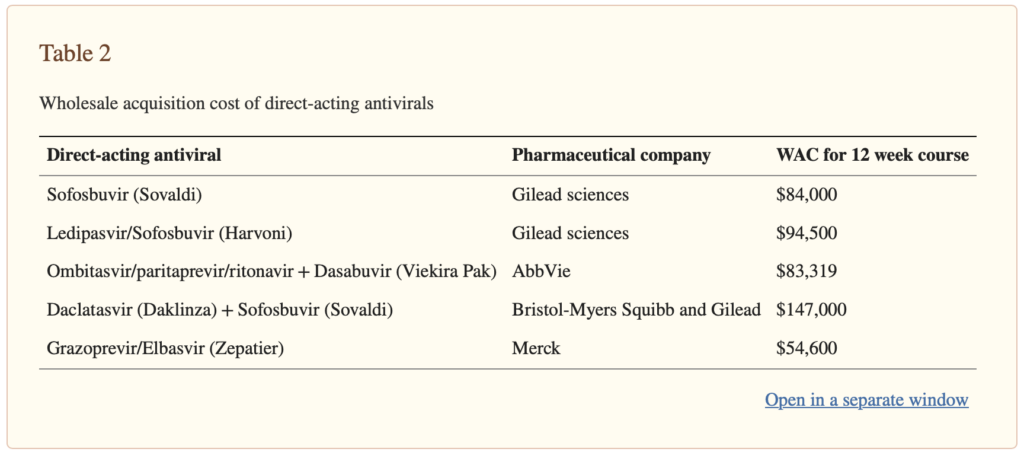

Direct-acting antiviral HCV medications, including Daklinza, Exviera, Harvoni, Olysio, Sovaldi, and Viekirax, cure HCV in a majority of patients after one course of treatment.

The issue is the cost.

The list prices of these medications range from $54,600 to $147,000 for a 12-week course of treatment. There are, of course, rebates and negotiations that go into the final price insurers will pay, but nonetheless, these prices are a lot more than your classic hypertension medication!

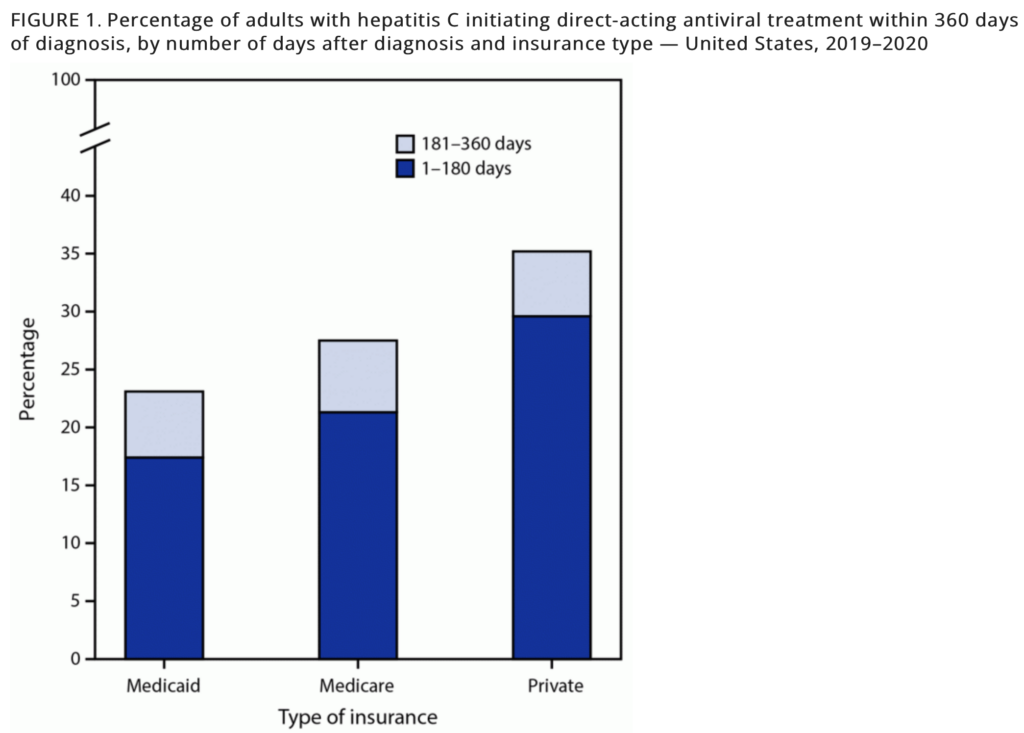

Since this is America, you know there’s a business behind pharmaceuticals: even if there’s curative treatment for HCV, it doesn’t mean you’ll get it for free. No matter the insurance coverage you have, access to these curative medications is limited.

Netflix Model for HCV Treatment

Given that curative HCV treatment has been inaccessible to a majority of people with the infection, Louisiana and Washington State introduced not-so-novel subscription models in 2019 to obtain access to the above-mentioned HCV medications. I say “not-so-novel” because the models function nearly identical to your Netflix subscription: the states pay a fixed annual fee to a pharmaceutical company in return for unlimited access to the drug.

Here’s how the model works:

- The states pay a yearly “subscription” to the pharmaceutical company for unlimited access to the medication.

- The states pay a reduced price per prescription through discounts (known as rebates) up to a certain spending threshold.

- Once the spending threshold is hit, additional discounts are added and the prescription price falls to nearly zero.

This approach offers states a clearer budgetary outlook for these medications while ensuring consistent revenue for drug manufacturers. Furthermore, it diminishes reasons to limit drug access; once purchased, subsequent prescriptions come at a minor cost due to the enhanced discounts after reaching a set spending limit.

Both states went into these partnerships with the mission to increase access to HCV treatment for Medicaid and incarcerated populations. Louisiana partnered with Gilead Sciences’ subsidiary Asegua Therapeutics for their Epclusa for five years, and Washington State partnered with AbbVie for their Mavyret for five years. Within one year of implementation, Louisiana aimed to treat and cure 10,000 individuals, and Washington aimed to treat and cure 4,900 individuals.

Those were lofty goals.

First, Louisiana saw a 160% increase in quarterly HCV prescription fills, averaging around 200 fills per 100,000 Medicaid enrollees. Washington, on the other hand, didn’t see any significant changes. This difference is likely due to Washington removing strict restrictions on HCV medications years before this model was introduced, while Louisiana removed such restrictions right before the subscription model. This move to ease restrictions on HCV medications might have initially allowed more people in Washington to get treated, thus not showing a drastic uptick after the introduction of the subscription model.

Second, Louisiana and Washington have been falling short of their elimination goals. As of September 2022 (three years post inception), Louisiana had treated fewer than 12,000 of the estimated 39,000 patients in its Medicaid and prison system, with treatment rates dropping. Moreover, the Washington Department of Corrections treated only 977 inmates between 2019 and 2021, with a mere 227 in 2021, despite an estimated 11% to 15% of the inmate population carrying the virus.

Dash’s Dissection

Perhaps more states should follow Louisiana and Washington’s subscription-based models to purchase medication supplies for public health purposes. While the results so far from Louisiana and Washington regarding treatment and cure rates may look less than stellar, it’s important to remember the context in which the programs were enacted: Covid hit several months later. So, those numbers you’re seeing from the STAT article I linked might not paint the full picture. Pandemic disruptions probably played a role. I eagerly await next year’s data, which will mark the program’s fifth anniversary.

Anyway, I’m a fan of subscription models for medications since they’re a form of value-based reimbursement. These models act as pull incentives and are attractive for pharmaceutical companies since they de-link revenue from sales volume, meaning companies don’t need to sell-sell-sell to make a lot of revenue. I described push and pull incentives as they relate to drug innovation in a previous newsletter here.

Now, if you had to choose another medication class for a Medicaid-based subscription model, which class would you choose?

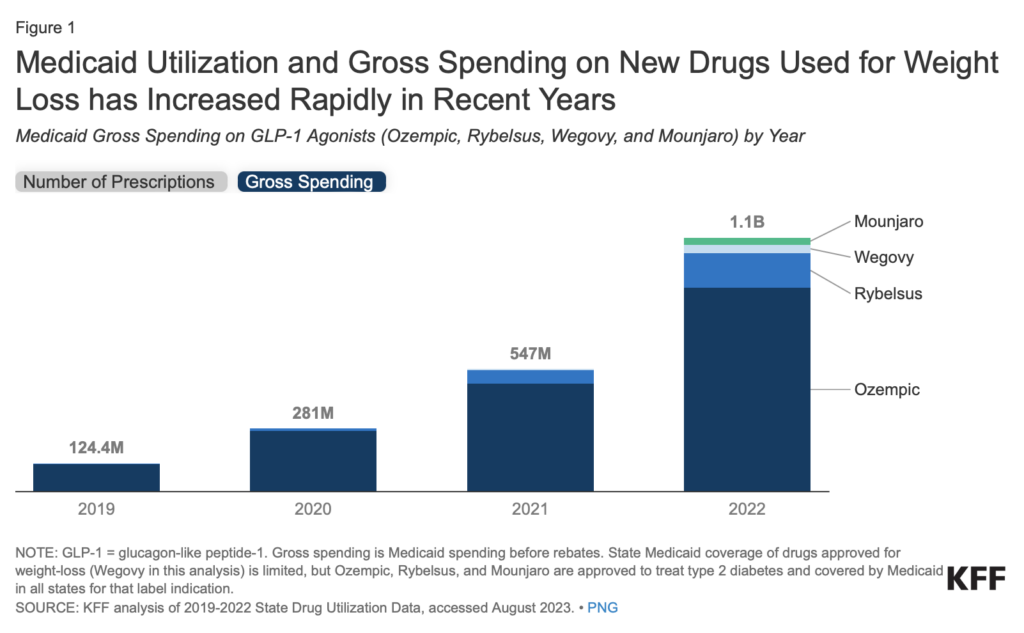

I’d choose GLP-1 agonists for type 2 diabetes and obesity (semaglutide, tirzepatide).

These medications are costly but effective. KFF estimated that Medicaid programs spent $1.1 billion on these GLP-1 agonists in 2022, with spending rates increasing substantially year-over-year. Implementing a subscription model could, in theory, increase access to these meds for Medicaid members and reduce the long-term costs of unmanaged diabetes and obesity.

But, getting the meds is just one piece of the puzzle. Whether we’re talking HCV, diabetes, or obesity, there are societal hurdles that stretch way beyond the prescription pad: easy access to medical professionals, up-to-date technology, diagnostic services, fresh foods, a solid support network, and even transportation. You can’t treat what you don’t know. Take HCV: If you’re unaware you have it because you couldn’t get tested or there’s no active campaign promoting screenings, then the best drug in the world won’t help. The same logic applies to diabetes.

In summary, while subscription models like those in Louisiana and Washington show promise and could be a game-changer for medications, the broader challenges in public health extend beyond just ensuring access to these drugs. Addressing the societal barriers from early diagnosis to treatment is crucial in making a tangible difference in patient outcomes.

Stay ahead in healthcare with my weekly Healthcare Huddle newsletter, covering digital health, policy, and business trends for 32,000+ professionals. Share with colleagues and subscribe here.