25 February 2023 | Healthcare

Prescription Predicament: How Three New Models are Tackling Drug Prices

By workweek

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services revealed three experimental models to improve drug affordability and access. Each model is unique, targeting different areas within the drug market that contribute to high drug prices.

While these are experimental models, they have the potential to reshape the drug market and improve the patient experience. So, let’s talk about it.

In this article, I’ll briefly discuss the current state of drug prices in the U.S., dive into CMS’s three experimental models to lower drug prices, and discuss key players tackling drug prices.

It’s The Prices, Stupid.

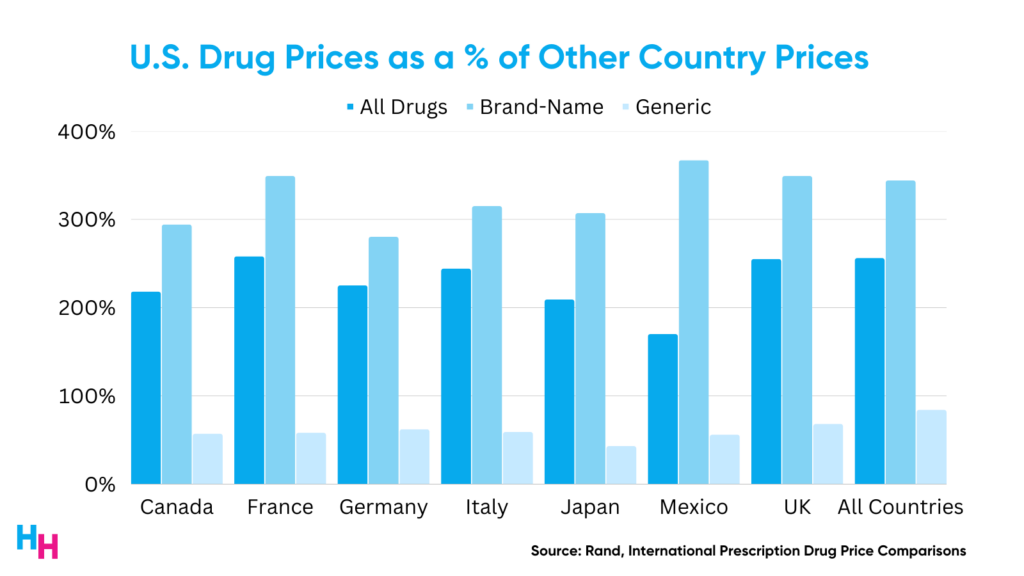

Drug prices in the U.S. are substantially higher than those of peer nations. For example, a Rand study found that U.S. drug prices in 2018 were 256% greater than those in 32 comparison countries.

Furthermore, it’s worth noting that in comparison to other countries, the prices of brand-name drugs in the U.S. were 344% higher. Conversely, the prices of unbranded generic drugs in the U.S. were only 84% of the comparison countries’ prices. This is particularly noteworthy because unbranded generic drugs constitute 84% of the total drug volume in the U.S., whereas they only make up 35% in the comparison countries.

Even when accounting for the net list price of drugs (adjusting the list price to the amount actually paid for the drug after rebates), drug prices were 150% greater in the U.S. than in the 32 comparison countries.

You get the point: drug prices in the U.S. are high. But why?

At a basic level, drug prices are so high because they can be—it’s the prices, stupid. At a more nuanced level, it comes down to three areas:

- The government’s lack of negotiation power (thank you, Medicare and Drug-Price Negotiation).

- Drug patents and market exclusivity (see my article on Humira).

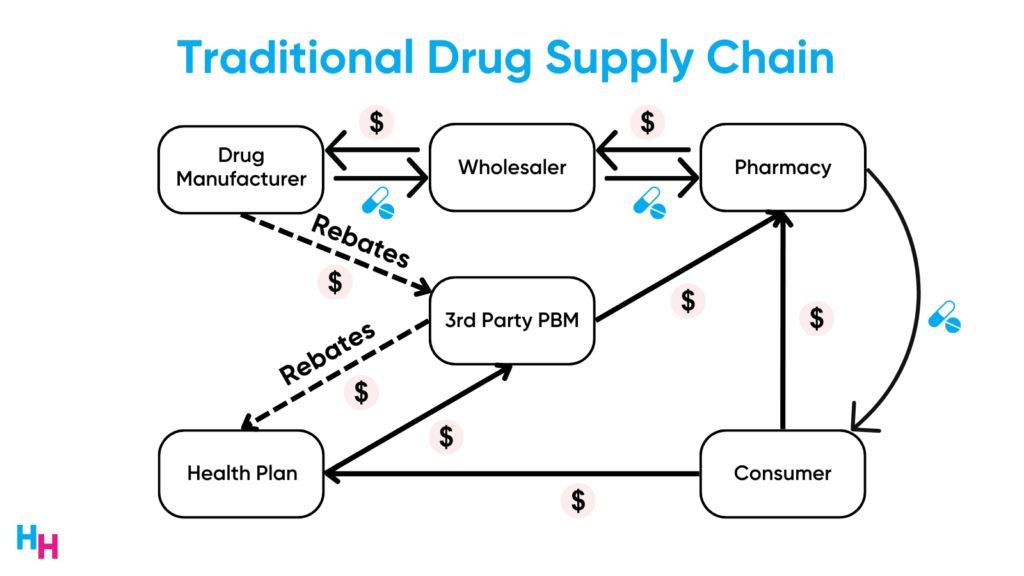

- Drug supply chain complexity.

These three areas have allowed drug manufacturers to price their drugs at whatever the market can tolerate: they have negotiation power, they have market exclusivity, and they take advantage of the opaque drug supply chain.

The main loser of high drug prices is—and always will be—the patient. Sure, high drug prices incentivize drug innovation for life-threatening conditions. But how do you explain drug prices rising faster than inflation? Or drug prices rising despite economies of scale?

The drug market is messy. We need innovative solutions to make it less messy.

CMS’s Three Novel Drug Pricing Models

Following President Biden’s executive order back in October, Lowering Prescription Drug Costs for Americans, CMS created three experimental models to improve drug access and affordability:

- Medicare High-Value Drug List Model

- Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model

- Accelerated Clinical Evidence Model

Each model targets more or less one of the three areas I listed above regarding why drug prices are so high. Each model also targets different beneficiary populations.

Medicare High-Value Drug List Model

The Medicare High-Value Drug List Model would create a standardized list of 150 “high-value” generic medications with a max copay of $2 for Part D plans. These high-value generic drugs would be for common, treatable chronic conditions like hypertension. This model would remove the need for step therapy, prior authorization, quantity limits, and pharmacy network restrictions—all of the annoying and frustrating aspects of accessing medications for patients.

The model standardizes generic drugs with known cost sharing. Physicians and patients will therefore know which drugs are on the list and how much the patient will pay for them ($2).

According to CMS, more than 5 million Medicare beneficiaries reported problems affording their medications, with 3.7 million reporting skipping their meds because of costs. But, of course, the affordability and access issue is not an equitable problem: Black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries reported 1.5-2 times more difficulty affording their meds than their white counterparts.

Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model

The Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) Access Model would allow state Medicaid agencies to give CMS the authority to coordinate and administer outcomes-based agreements (OBA) with CGT manufacturers.

CGTs are life-changing medications but are prohibitively expensive (e.g., ~$500,000/treatment course) for the Medicaid population. There are currently 26 approved CGTs that treat diseases like Sickle Cell Disease and cancer. The CGT market is picking up, though: around 50 more CGTs will hit the market in 2024 and over the next decade, an estimated one million+ Americans may use a CGT to treat a condition they have, increasing annual CGT spending to $25 billion.

The CGT Access Model essentially leverages CMS’s negotiating power over drug manufacturers. If multiple—or all—state Medicaid agencies give CMS the power to coordinate and administer OBA, drug manufacturers may be left with no other option than to partake in such an arrangement. These OBAs shift risk to the manufacturer to ensure their CGTs are high-value and cost-effective.

CMS proposed three ways to implement such OBAs:

- Outcomes-based payments: pay drugmakers a portion of the CGT price upfront and subsequent payments based on clinical milestones.

- Outcomes-based rebates: pay drugmakers the full price of CGT upfront and then have the drugmaker send back rebates if clinical milestones are not achieved.

- Outcomes-based annuities: pay drugmakers a fixed amount of the CGT price over time if beneficiaries receiving the CGT continue to surpass clinical milestones.

These OBAs shift risk to the drug manufacturer, so they obviously won’t like this proposal. But, it will benefit Medicaid beneficiaries who struggle to afford life-saving CGTs.

Accelerating Clinical Evidence Model

The Accelerating Clinical Evidence Model would adjust Medicare Part B fee-for-service payments for drugs granted accelerated approval by the FDA.

To explain how this model works, I need to provide a quick background on the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway, which I discussed in-depth in a previous newsletter here.

- The FDA’s Fast Track program expedites life-saving drugs to market, with the confidence that these drugs are indeed effective.

- The FDA requires drug sponsors to perform confirmatory trials after the drug’s Fast Track approval to confirm the drug’s clinical benefits. If confirmatory trials do not support the drug’s efficacy, the drugmaker is to remove the drug from the market.

- The big problem: drug sponsors seldom perform their confirmatory trials and refuse to withdraw drugs lacking evidence of clinical benefit.

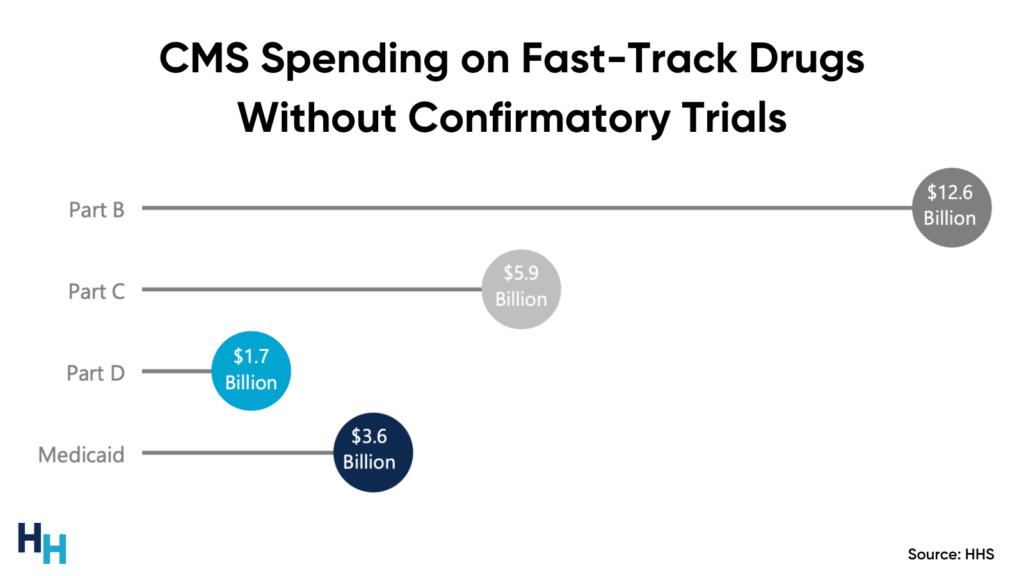

CMS paid at least $18 billion (Part B = $12.6 billion) between 2018 and 2021 for fast-track approved drugs whose sponsors had yet to perform confirmatory trials.

Who suffers the consequences of such spending on fast-track drugs without confirmatory trials? Medicare beneficiaries, who face increased Part B premiums to help Medicare pay for these fast-track drugs (e.g., Biogen’s Alduhem increased Medicare Part B premiums by 15%).

So, in this Accelerating Clinical Evidence model, Part B payments for fast-track approved drugs are adjusted to incentivize drugmakers to expedite their confirmatory trials. In turn, trials that don’t confirm a drug’s efficacy are removed from market. Medicare Part B would not have to pay for the expensive drug, saving beneficiaries from increased premiums.

Dash’s Dissection

There’s increasing momentum among companies and governments creating innovative solutions to increase affordability and access to medications. All of these solutions tackle at least one or more of the key problems leading to high drug prices, which I stated above:

- The government’s lack of negotiation power.

- Drug patents and market exclusivity.

- Drug supply chain complexity.

The three models I discussed tackle all of these areas. The Medicare High-Value Drug List Model increases transparency of the opaque drug supply chain; the Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model gives the government more negotiation power and ensures these CGTs, which have market exclusivity, are paid for based on value; and, the Accelerating Clinical Evidence Model ensures drugs that are expedited to market (with or without exclusivity) are actually clinically effective.

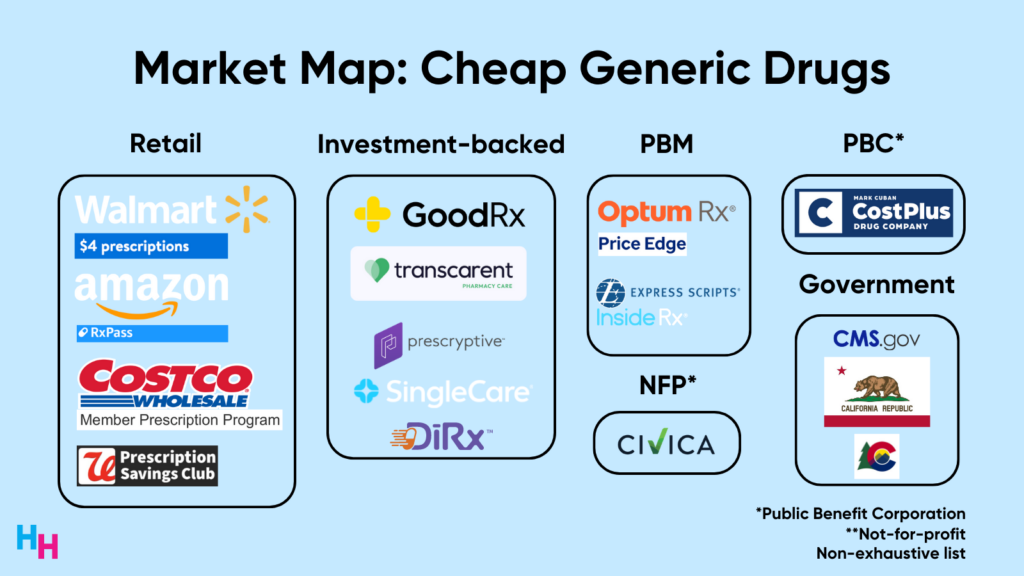

While CMS’s models tackle each of those key problems stated above, corporations seem to focus solely on the drug supply chain complexity. By targeting the drug supply chain, these corporations can lower the price of their generic medications. For example, Walmart has its $4 prescriptions program, Amazon just released RxPass, Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs offers 1,000+ generic drugs cheaper without insurance than with insurance, and Civica is working to make insulin more affordable.

Overall, here’s the big picture I see: there’s a war on unaffordable and inaccessible medications. Corporations are battling the complexity of the drug supply chain while the government is building its negotiation power and leveraging its policymaking capabilities. The “winner” of the war won’t be the government or the corporations. It will be patients.

In summary, drug prices in the U.S. are unaffordable and inaccessible, with as many as 30% of Americans reporting not taking their meds because of costs. To improve access to affordable medications, CMS has released three experimental models that address the government’s negotiation power, drug patents/market exclusivity, and drug supply chain complexity. These models target some or all of these areas and focus on unique beneficiary populations. Overall, momentum is picking up—from the government and corporations—to increase the affordability and accessibility of needed medications.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, share it with colleagues. Sign up for the Healthcare Huddle newsletter here.