21 May 2023 | Climate Tech

Under-discussed energy transition metals

By

Climate tech analysts and energy transition naysayers alike expend a lot of breath and real estate in newsletters, reports, and on the timeline on the projected scarcity and concentration of various inputs to climate technologies. Lithium, a mainstay of EV and grid-scale energy storage batteries, and copper, a key ingredient for most all electrical systems, are prominent examples.

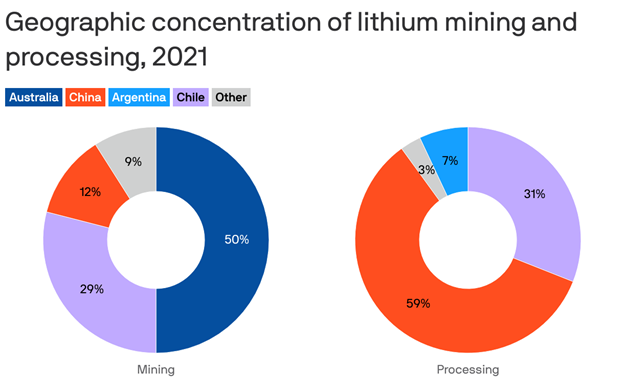

However, in the same way lithium processing and production is concentrated in a few countries (see above), conversations about metal and mineral scarcity are also often concentrated on, well, a few metals. It’s worthwhile to open our aperture wider and to think about all the other inputs into the energy transition, including for metals that are:

- So ubiquitous we forget about them

- So obscure you’ve never heard of them

Two deals from this week will allow us to do just that::

- Alloy Enterprises raised a $26M Series A to 3D print aluminum parts for EVs and other industries

- Noveon Magnetics raised a $75M Series B to make neodymium magnets

Do you say a-lu-mi-nium or a-lu-minum?

I’ll make fun of you if your answer to the above is the former. But regardless of your answer, aluminum is everywhere. It’s in cars. It’s in cans. It’s in your cooking utensils.

It’s also in EVs in spades, even more so than in cars with internal combustion engines. EV batteries are heavier than internal combustion engines, leading many electric auto manufacturers to look for weight-saving opportunities elsewhere.

Using more aluminum offers one such opportunity; aluminum is only about one-third as dense as iron or copper. The Ford F-150 Lightning has almost 700 pounds of aluminum content.

And – to illustrate why even metals like aluminum require thought and analysis regarding the energy transition and climate tech – Ford recently came under fire for sourcing aluminum from mines in the Amazon that contaminated the region’s water supply.

Alloy Enterprises is also focused on making aluminum more efficiently. Theirs isn’t a wholesale overhaul of aluminum production by any means. Instead, they want to make aluminum parts manufacturing incrementally better to save on time, energy, material input requirements, and $$$.

The firm isn’t rolling out aluminum parts to partners yet, but they anticipate differentiating themselves through various additive manufacturing (building things up, i.e., ‘adding,’ rather than winnowing things down) techniques, laser cutting, and diffusion bonding. One significant value proposition will be eliminating the need for aluminum powder for adhesion, making their parts more recyclable.

Incremental improvements are admittedly less sexy than discussing an entirely new lower-carbon aluminum manufacturing process would be. But aluminum production contributes approximately 3% of all global greenhouse gas emissions, so all process and production improvements (and enhanced recycling) are welcome. The CO2 intensity of aluminum production has fallen slightly over the past 20 years. Maybe additive manufacturing can deliver more meaningful reductions.

As almost always with metal-focused conversations these days, there’s also an onshoring component to the Alloy story. The company is based out of Boston, and if they can scale, they’ll be a welcome counter to, you guessed it, China, which produces more than half the world’s aluminum.

A rare earth metal, for real

I wouldn’t be surprised if you’d never heard of neodymium before. Which isn’t to say it isn’t essential; neodymium magnets feature readily in many industrial motors, EVs, and other electrical systems. While lithium is not a ‘rare earth metal’ but is often conflated with them, neodymium is one of 17 rare earths. And the market for its production and refinement is as concentrated as other metals that are key to the energy transition:

Considering the breadth of their application, more than half the neodymium sold globally is used to make ‘permanent’ magnets (magnets with persistent magnetic fields).

While the U.S. has ample rare earth reserves, plenty of companies are tweaking their tech (or rolling out entirely novel technologies) to reduce the need for things like neodymium magnets or other rare earth metals; concerns about price and future availability are sufficient to drive these shifts.

Noveon Magnetics, meanwhile, aims to make a large share of its neodymium magnets with neodymium recycled and reclaimed from other technologies, ranging from EVs to hard drives. The more recycled neodymium it can use, the more:

- Resilient its supply chain will be

- Its lifecycle emissions will fall (less mining)

- It can keep costs down

- It can attract business from sustainability-minded buyers

- The more it will appeal to domestic auto OEMs

There’s a bunch of tailwinds that tie in here. The first is the interest in the big business opportunity inherent to recycling scarce materials. Companies like Redwood Materials (recycling EV batteries) have raised billions on that pitch.

Onshoring and de-risking dependence on China is, again, a big driver here. Noveon’s focus on recycling and reclamation could ultimately have big supply chain resilience benefits (if, as always remains an open question, it can scale).

The net-net

There are no silver bullets nor panaceas in climate tech, just a labyrinthine web of tradeoffs, complex supply chains, and contrasting conclusions from lifecycle emissions analyses. Few materials, whether ones we discuss often or ones we don’t, are exempt. Most come with some environmental burden, energy input requirement, and emissions footprint.

This is a feature, not a bug, of the energy transition. It’s not enough to swap combustion engines for batteries. You gotta embrace the opportunity to think about the entire vehicle from the ground up and everything it’s made of. It’s onerous work, but it’s also kind of, I don’t know, fun at times? Leave no stone unturned.

Of course, that’d be too much work for any one company, so it’s good to see firms like Noveon and Alloy zeroing in on relatively niche applications.