28 February 2024 | FinTech

It’s Time to Bring Identity Verification and Fraud Prevention Back Together

By Alex Johnson

My philosophy for personal security is centered around access control. If I keep my doors and windows locked, especially when I’m not at home, I generally feel like all of my stuff will be safe.

My sons, who are five and three, have a very different philosophy.

They watch their stuff. They watch it very, very closely. Whatever stuff they’ve decided is most important to them at that moment – toys, books, etc. – they watch it the way that security guards at the Louvre watch the Mona Lisa. It’s remarkable. They’ll tuck it into their beds when they go to sleep, and it’s the first thing they think about when they wake up at 5:00 AM, as if their subconscious minds had been focusing on nothing else for the previous 10 hours.

I try to tell them to calm down. I try to reassure them that their stuff is safe. But still, they persist with their Mad-Eye Moody-level vigilance.

And honestly?

It makes sense if you think about it from their perspective.

Unlike me, they have no control over access to the house. To them, our house is a circus of tall humans, all coming and going at somewhat random and unpredictable intervals. Sometimes it’s someone they know well (like a grandparent), but oftentimes it’s someone they don’t know and didn’t invite (why is that guy fixing our fridge?)

To them, the only sensible model for keeping the stuff they care about safe is to focus on that stuff, exclusively.

Don’t worry about the front door. Worry about your Legos.

If you look at the current state of fraud management in financial services, what’s interesting is just how similar most banks and fintech companies are to my kids.

Everyone is watching their stuff. Almost no one is watching the front door.

The Current State of Fraud Management in Financial Services

For the last couple of years, Alloy has surveyed decision-makers in fraud-related roles at financial services companies, in order to get a pulse on how companies are navigating the challenges associated with detecting and preventing fraud.

Their most recent survey, which resulted in the company’s 2024 State of Fraud Benchmark report, included 250 decision-makers across fintech companies, online or pure-play lending institutions, enterprise banks, mid-market banks, regional banks, and community banks/credit unions in the U.S. (they also surveyed 200 decision-makers at similar companies in the UK).

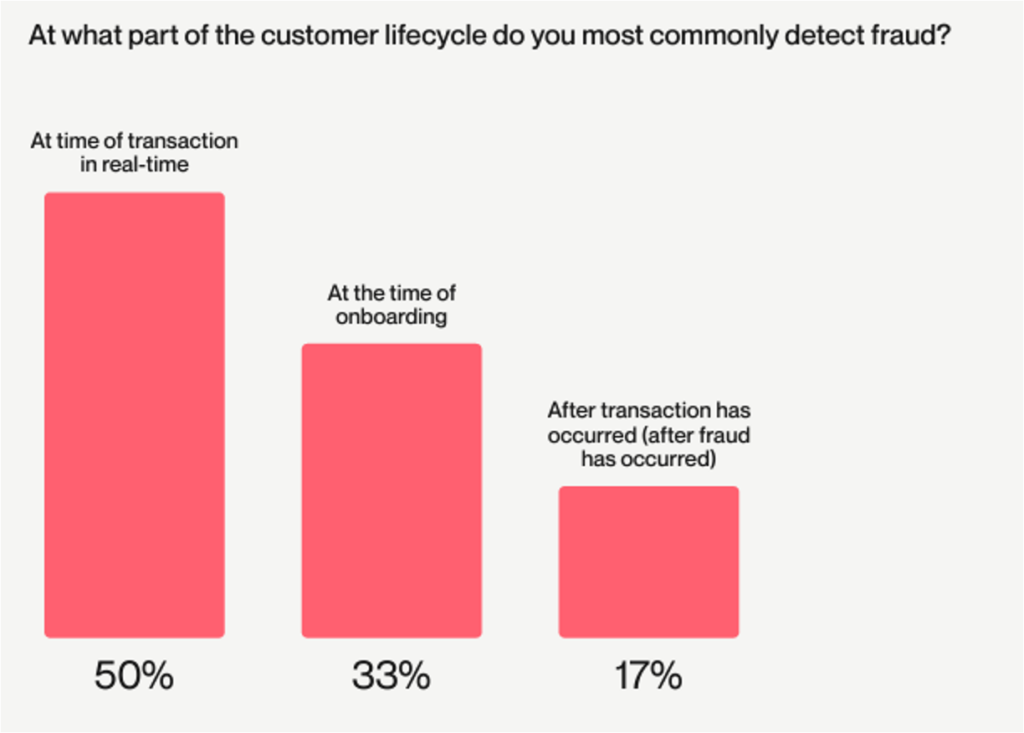

The most interesting finding, to me, was where fraud is most commonly detected in the customer lifecycle:

50% of respondents said they most commonly detect fraud in real-time during the transaction. That percentage is consistent with the prior year’s survey.

However, there was a 10% decrease YoY in respondents’ likelihood of detecting fraud during the onboarding process.

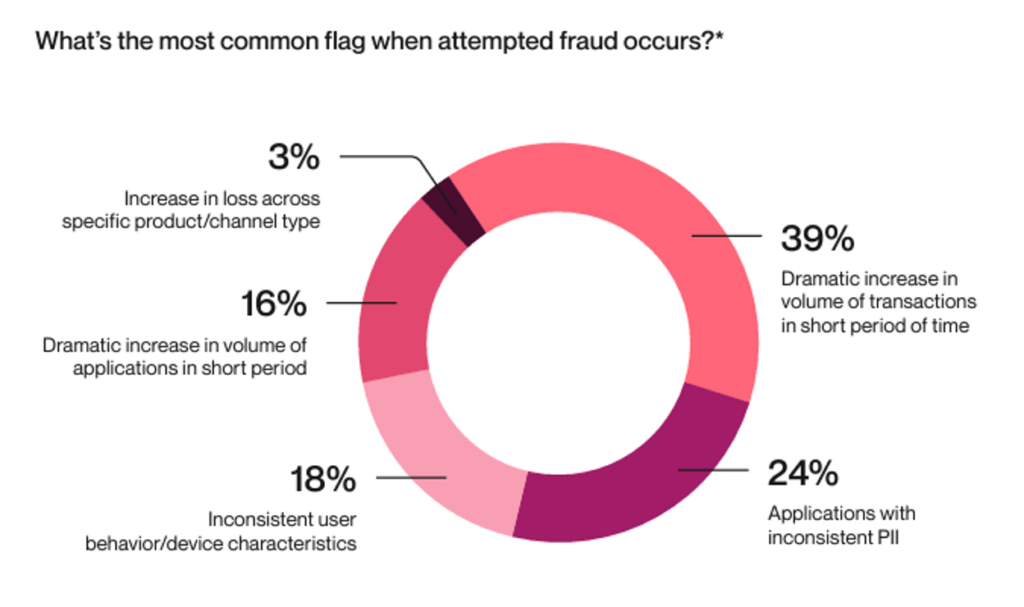

Drilling in a bit more, when Alloy asked financial services providers which specific flags they most commonly use to detect fraud, the most popular answer was a “dramatic increase in the volume of transactions in a short period of time”:

Interestingly, the number of survey respondents who said that the most common fraud flag was a “dramatic increase in the volume of applications in a short period of time” actually went down by 5% YoY.

What are we to make of this?

Well, put simply, financial services providers are becoming increasingly reliant on real-time transactional fraud detection (watching your stuff), and correspondingly less reliant on identity-based fraud detection during account onboarding (watching the front door).

This is a strange approach!

And it creates problems. For example, it gives financial services providers a skewed view of their fraud challenges.

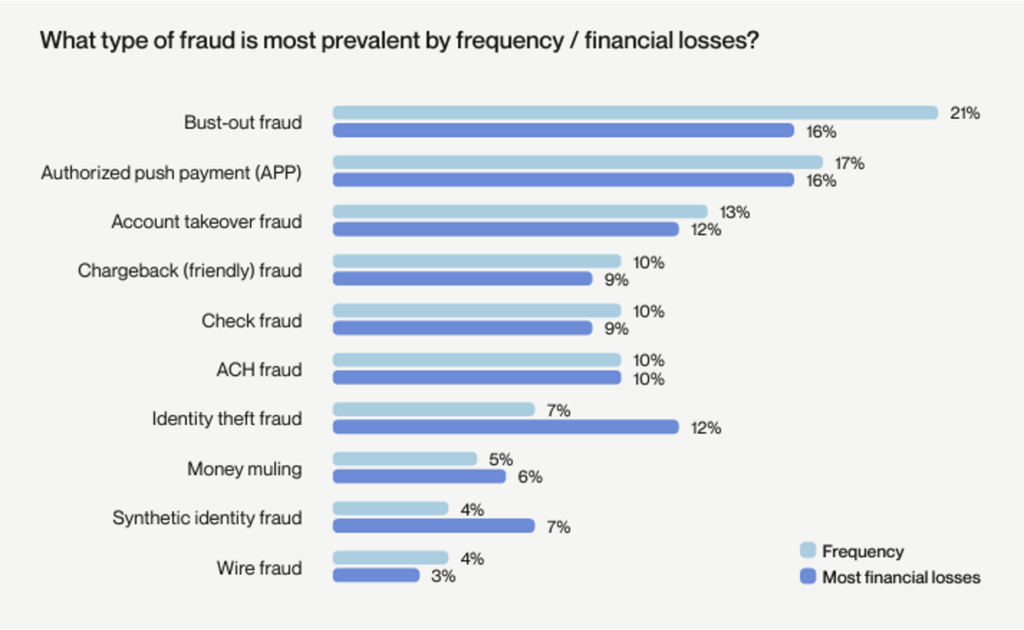

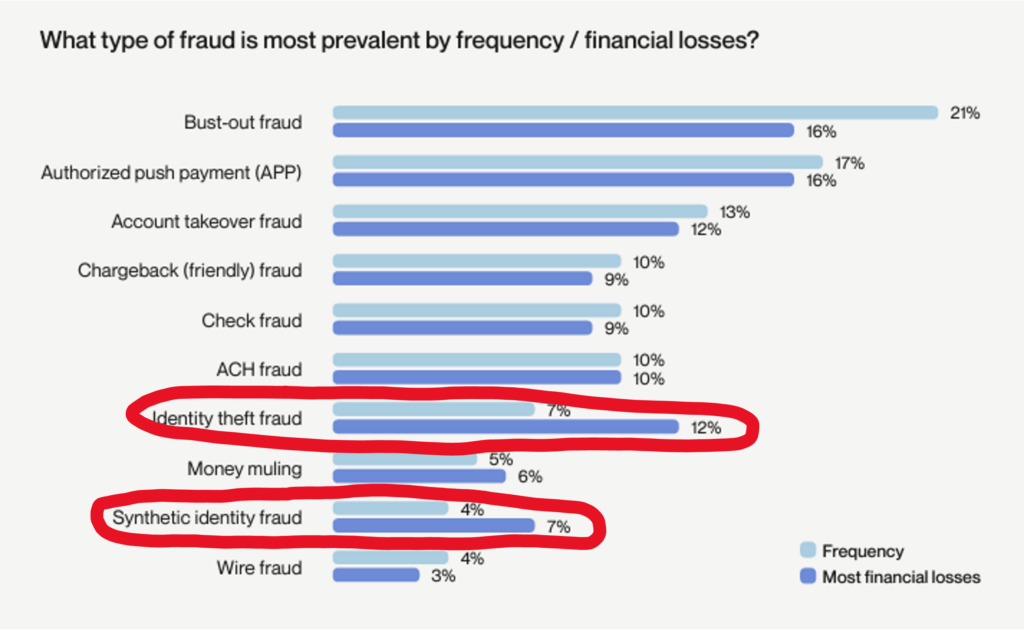

In its survey, Alloy asked what type of fraud is most prevalent by frequency and total financial losses. The four most popular answers were “bust-out fraud”, “authorized push payment”, “account takeover”, and “chargeback (friendly) fraud”:

But look at two of the answers that are lower down on the list:

Two of these things are not like the others!

Identity theft and synthetic identity creation are the mechanisms by which most other types of fraud are perpetrated (and in the case of friendly fraud or first-party fraud, they are also the cause of a lot of misclassification of fraud losses).

From a first principles perspective, it makes absolutely no sense to say that you have a bigger bust-out fraud problem than you do a synthetic identity fraud problem.

No! You have a big bust-out fraud problem because you (likely) have a big synthetic identity fraud problem! One is a disease, and the other is a symptom! That’s why identity theft fraud and synthetic identity fraud have significantly bigger reported percentages in the “most financial losses” category than the “frequency” category.

Identity fraud is a systemic problem. Transactional fraud is a tactical problem.

So, why do financial services providers spend most of their time and resources focused on the tactical problem rather than the systemic problem?

That is a great question!

To answer it, we need to examine how banking in the U.S. has changed over the last 30 years.

How Banking Changed

Two of the most impactful trends in modern U.S. financial services history started in 1994.

The first was the World Wide Web. In 1994, Tim Berners-Lee left CERN and founded the International World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), the Mosaic web browser – one of the earliest web browsers, capable of multimedia browsing – became available across PC and Macintosh computers, and the number of web servers increased from 500 to more than 10,000, which helped get more than 10 million people online for the first time.

The second trend was interstate banking. In 1994, President Clinton signed the Riegle–Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act into law. It allowed banks to branch across state lines and allowed bank holding companies to acquire banks in any state, regardless of state law.

Now, obviously, neither of these developments transformed the financial services industry overnight. However, they led to tectonic shifts over the following decades in how banks served their customers and competed with each other.

Specifically, three big changes came out of the collision of the internet and interstate banking:

1.) Identity became probabilistic.

The transition from a local, branch-centric distribution model to a national, digital-centric distribution model created several challenges for banks. One of the biggest was identity verification. In-branch identity verification is a highly deterministic process for meeting Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements – a person who is likely known to your employees walks into your branch and asserts their identity using a government-issued ID. While identity fraud certainly isn’t impossible in branches (indeed, it has seen a bit of a resurgence lately as fake IDs have gotten more sophisticated and a new generation of fraudsters have discovered check fraud), it’s comparatively rare because it’s difficult, expensive, and risky for a fraudster to pull off. On the other hand, identity fraud in digital channels is much more common because digital channels don’t have the same constraints. This makes digital identity verification much more of a probabilistic exercise – you are constantly assembling all of the individual identity signals that you are collecting (PII, device, location, behavior, etc.) and using it to make an educated guess on whether someone is who they say they are.

2.) Financial services became faster and more accessible.

One of the big upsides to this shift to a national, digital-centric distribution model in financial services is that financial products have become far more convenient for consumers to access and engage with. Over the last 30 years, speed has become the hallmark of well-run, customer-centric financial services providers. Companies are now measured by their customers not on how far away their branches are from the customers’ homes nor on how friendly their customer service staff is (though those are still important), but rather by how fast their digital account opening process is and how quickly customers can get access to their paychecks or pay their landlord.

3.) Banking became more competitive.

While interstate banking definitely hastened the pace of consolidation in the U.S. banking system, it also significantly broadened the competitive surface area in financial services. Suddenly every bank in every market was competing with every other bank in every other market. And because of the rise of digital channels, consumers’ ability to research financial products and make more informed product decisions (rather than just accepting the crappy cross-sell offer from their existing bank) improved drastically. This increased competitive pressure pushed some banks to grow even faster through M&A. It pushed others to innovate on their products and services. And it pushed a few smaller ones to explore creative new partnership models, which led to the emergence of banking-as-a-service (BaaS) and much of the fintech ecosystem we have today.

ZIRP Pours Gas on the Fire

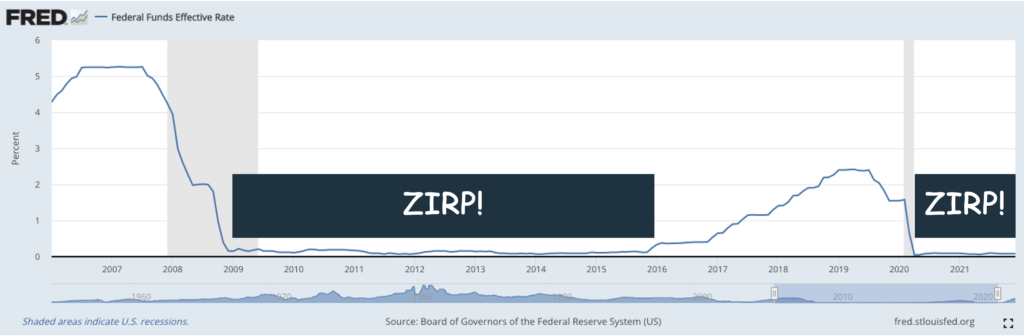

All three of these changes were further accelerated by the sustained zero-interest-rate policy (ZIRP) period that we experienced between 2009 and 2022:

Fintech exploded, thanks to LPs’ enthusiasm for VC and VCs’ enthusiasm for fintech. This ratcheted up the level of competition in financial services.

This increased competition drove banks to invest significantly in improving the speed and accessibility of their products and services, often at great risk (see: Zelle), which made already-tenuous digital identity verification processes that much more precarious.

And, of course, it wasn’t just banks and fintech companies that saw a boost during these years. The bad guys evolved as well:

- Fraud became significantly cheaper to do at scale. The rise of digital account opening significantly reduced the costs for fraudsters to open new accounts, and the growing use of online and mobile banking made account takeovers easier and cheaper as well.

- The surface area for fraudsters to attack got much bigger. The combination of digital channels and interstate banking suddenly made every existing bank a target, and the emergence of BaaS, fintech, and embedded finance gave fraudsters a lot of additional small (and often soft) targets.

- The increased speed and accessibility of financial services made fraud easier. As we’ve seen with Zelle and account-to-account payments in the UK, faster payments = faster fraud. And the ability for fraudsters to digitally open accounts with smaller and less sophisticated financial services providers and connect those accounts together via open banking makes it much easier to move money in and out of the system. That second advantage for fraudsters is compounded by legacy banking infrastructure providers like Early Warning Services (EWS) locking fintech companies out of their fraud data consortiums.

- Fraudsters pivoted into infrastructure. In much the same way that many B2C fintech companies have pivoted, over the last 10 years, into selling their technology and expertise to other fintech companies and banks, we’ve seen a similar SaaS-ification in fraud. There is now a robust fraud-as-a-service (FaaS) market on the dark web, with experienced fraudsters selling their tools, time, and expertise to paying clients for tasks like account takeovers, payment fraud, synthetic identity creation, refund fraud, account farming, and money laundering, among many others.

- Fraudsters likely got a big R&D boost during the pandemic. As has been widely reported, fraudsters stole a lot of money – as much as $280 billion – from the federal government, through COVID-era stimulus programs such as the Paycheck Protection Program. While it’s unknown exactly how much of that money was stolen by fraud rings and other organized groups, it’s obviously more than $0, which is great for them (free money to invest in the business!) and terrible for the rest of us (more sophisticated fraudsters!)

All of these changes, which have happened at an unprecedentedly fast rate, have left banks in a tough position.

Where Banks Are Today

When you understand the history, it’s easier to understand why banks’ fraud detection and prevention strategies are as tactical, decentralized, and reactive as they are.

In an ideal world, you’d want to build your fraud management strategies on a cohesive, cross-product, omnichannel infrastructure. You’d want to focus on identity verification and authentication first, and fraud detection and prevention second, recognizing the essential truth that fraud sits downstream of identity. And you’d want to be as proactive and collaborative as possible in countering emerging fraud trends and tactics.

Banks do not operate in an ideal world. They operate in the real world.

In the real world, banks have been forced to compete on a best-of-breed basis in every financial product category that they want to play in, often against monoline providers and fintech startups that specialize in those categories. This has pushed banks to adopt a more siloed and decentralized organizational structure, with each business line running its own P&L.

In the real world, banks have been pressured to keep pace with the experiential innovations of fintech competitors, while continuing to maintain and support the existing experiences and channels that many of their customers (particularly the older and wealthier customers) prefer. This has required banks to spread their resources out across a huge number of different channels and customer touchpoints, each with its own quirks and risks.

In the real world, banks have struggled to adapt to an ecosystem in which fraudsters are increasingly sophisticated, well-coordinated, and able to rapidly test and learn through attacks against small, inexperienced fintech startups. This has incentivized banks to become more reactive and proprietary in how they attempt to discourage fraudsters from attacking their own institutions.

To return to my personal security analogy, it’s as if banks moved from a single-family home into a frat house. It’s all doors and windows (none of which ever get locked) and random people coming and going at all hours of the day and night.

You can’t really blame them for holing up in a corner of the house and keeping a careful watch on their possessions.

The Status Quo is Untenable

It’s understandable why fraud management has become somewhat disconnected from identity verification.

It’s understandable, but it’s not tenable.

According to the FTC, Americans lost a record $10 billion to fraud in 2023, up from $1.6 billion in 2013.

That’s a massive increase, and, if you read between the lines a little, it’s evident that fraud management professionals working at banks and fintech companies don’t feel prepared to stem that rising tide.

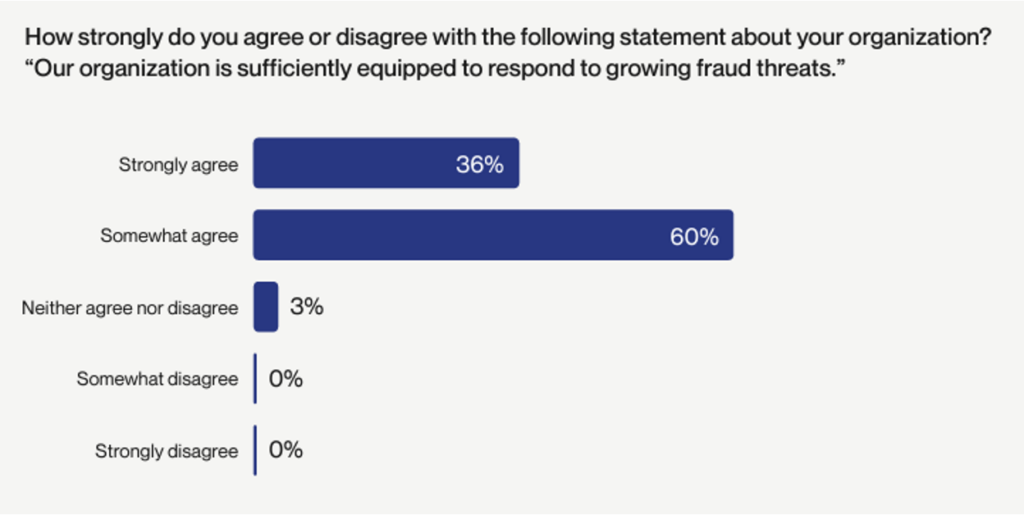

When they were asked in the Alloy survey to agree or disagree with the statement, “Our organization is sufficiently equipped to respond to growing fraud threats,” 36% strongly agreed and 60% somewhat agreed:

Now, of course, no one whose job it is to stop fraud will say, “We’re completely unprepared to stop fraud!” They might as well say, “You should fire me because I’m terrible at my job.”

However, the fact that 60% somewhat agreed with the statement rather than strongly agreed with it tells me that these folks, while confident in themselves and their organizations, understand (and are perhaps a bit daunted by) the magnitude of the challenge they’re facing.

(Editor’s Note – interestingly, the likelihood of a respondent strongly agreeing with the sufficiently equipped statement actually went down the more senior their role was, indicating that the more experienced and secure you are in your job, the more likely you are to be realistic about the challenges of fighting fraud.)

This lurking uncertainty makes sense when considering just how suboptimal these institutions’ fraud management tactics are today. For example, according to Alloy’s survey, do you know which step-up authentication method saw the biggest increase in use, when responding to transaction fraud alerts, between 2022 and 2023?

Knowledge-based authentication (KBA) questions.

KBA questions!

That’s insanity. Given the massive number of data breaches that consumers have been exposed to over the last 15 years and the resulting ubiquity of personally identifiable information (PII) available to fraudsters on the dark web, it’s actually easier today for a fraudster to answer KBA questions than it is for the average legitimate consumer.

As an industry, we need to do better.

What Does Better Look Like?

Again, banks and fintech companies operate in the real world, not in an ideal world, so I want to make sure I frame this portion of the essay in the most pragmatic way possible.

Would it be great if U.S. legislators and policymakers woke up tomorrow and decided that they were going to design and operate a national identity infrastructure in which the government was the primary issuer of digital identity credentials?

Yes, it would!

But that’s not going to happen.

So instead, let’s talk about ideas that can happen (and, indeed, already are happening).

There are three big ones that I want to touch on.

1.) Create a centralized financial crime management function.

This one is already well underway at forward-thinking banks (and it is the default organizational structure that many fintech companies are starting with).

The basic idea is to create an enterprise group to holistically oversee all financial crime management functions across the company.

For banks, which have evolved over the past three decades into highly decentralized, siloed organizations, in which financial crime management is an embedded function within each channel and line of business, this is quite a change.

It requires banks to pull back all of those embedded functions into a centralized group that works across all lines of business, all channels, all parts of the customer lifecycle, and across both fraud and KYC/AML functions (hence why it’s referred to, broadly, as financial crime management).

The benefit of a centralized financial crime management function is that it provides the company with a comprehensive view of the financial crime and identity-related risks that it faces and more control to respond in an intelligent and coordinated fashion to those risks. Instead of a fraud ring being able to sequentially hit different lines of business at the same institution, one after the other (which is depressingly common today), a financial services provider can quickly identify and protect its entire business against emerging threats.

The challenge of a centralized financial crime management function is that it can, if not implemented properly, reduce the effectiveness of specific frontline controls. Each line of business, channel, and part of the customer lifecycle faces threats that are specific to them. Under a centralized financial crime management structure, those frontline groups must retain the flexibility to tailor their controls to manage risk without adversely affecting the business. Additionally, the performance of the centralized financial crime management group needs to be synchronized with the performance expectations of the various business units, so that everyone’s incentives are aligned.

2.) Invest in an integrated identity platform.

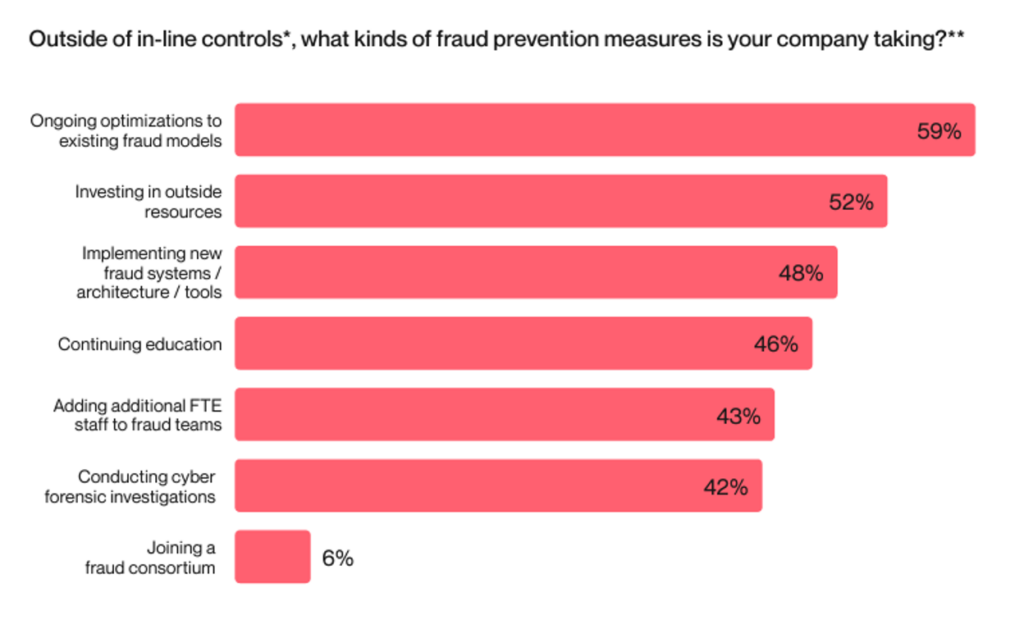

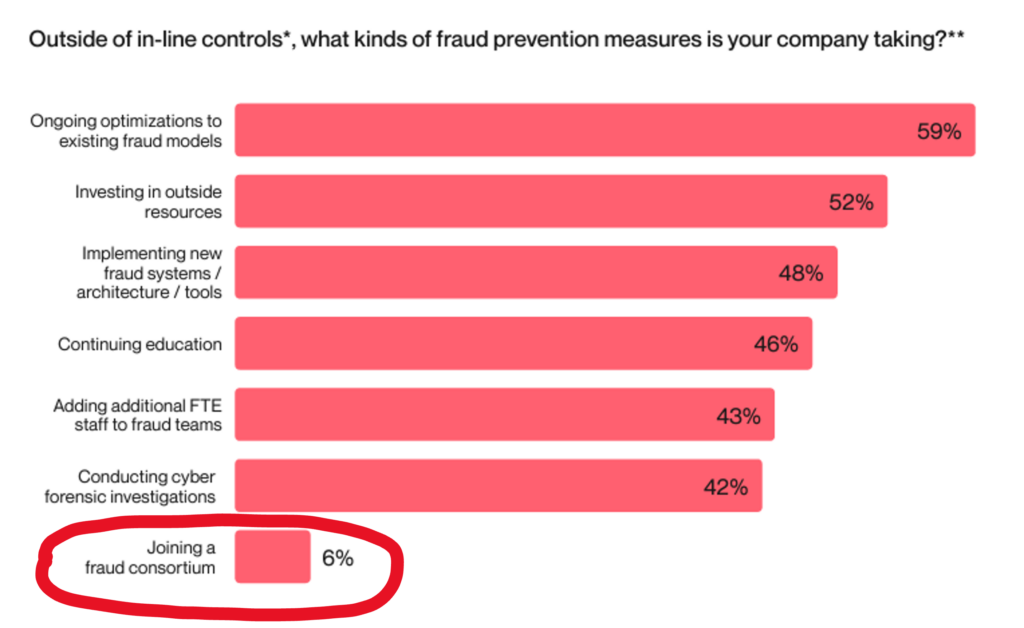

In its benchmark survey, Alloy asked fraud decision-makers what their organizations were prioritizing (outside of in-line controls like KBA questions) to help prevent fraud. Here are the top answers:

This came as a surprise to me.

Optimizing existing fraud models (which power the real-time transactional fraud detection processes that financial services providers rely so heavily on) is helpful, as is hiring outside consulting firms to shore up internal teams, but neither of those categories of investment has the potential to fundamentally transform these organizations’ approach to stopping fraud.

Implementing new fraud systems/architecture/tools might.

How do I know?

According to Alloy’s survey, mid-market banks were both the most likely segment of respondents to have seen a decrease in fraud over the prior 12 months and the most likely to have implemented new fraud systems.

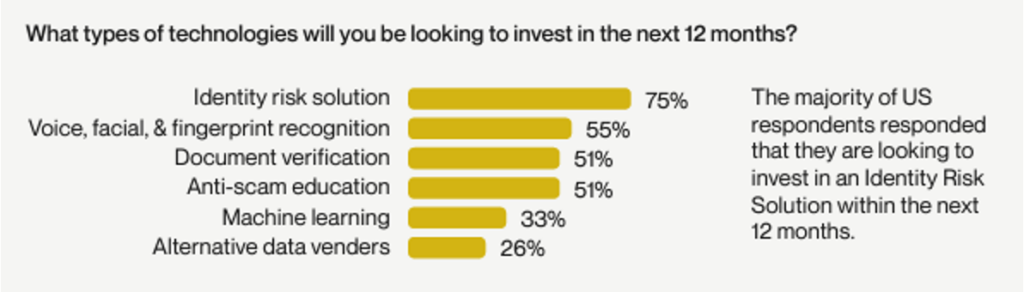

What type of fraud systems?

Well, I’m glad you asked!

According to the survey, identity risk systems are all the rage these days. A whopping 75% of respondents reported that they were planning to invest in such systems over the next 12 months:

Liminal, a market research firm focused on the digital identity space, uses a slightly different term – integrated identity platforms (IIPs) – to describe this same type of system.

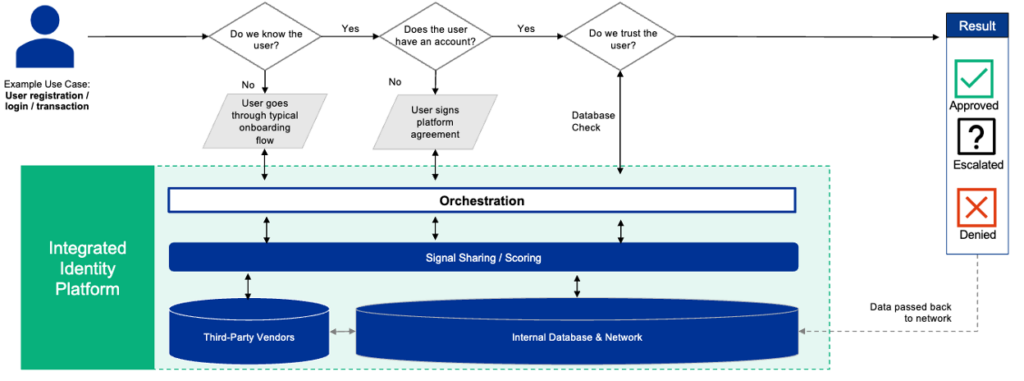

Here is how Liminal defines an IIP:

IIPs are end-to-end solutions that tie features across the consumer lifecycle together through orchestration to create a streamlined journey for end users and a simplified tech stack for enterprises.

With key capabilities and features across the consumer lifecycle, tied together through orchestration and network signal sharing, IIPs enhance UX, prevent complex fraud attacks, and provide a holistic customer view to enterprises.

If that sounds exactly like the type of system that a financial services provider intent on creating a centralized financial crime management function would want to build around, you’re right.

Here’s a graphic from Liminal showing how an IIP can orchestrate a more holistic identity verification and authentication workflow while helping the entire organization streamline its use of best-of-breed third-party vendors and better share intelligence on emerging threats:

Sounds just like the thing we need!

No wonder Liminal projects the market for IIPs to grow at a nearly 25% CAGR over the next three years.

3.) Share data.

Do you know what else was a surprise from the Alloy survey question about fraud prevention priorities?

“Joining a fraud consortium” coming in dead last:

Data sharing is critical to fighting fraud, particularly at a time when the competitive surface area in financial services has never been so big and when opening new accounts and transacting with them has never been faster or easier.

Banks and fintech companies can’t let competitive concerns – like those that have apparently motivated EWS to disallow fintech companies to contribute to or buy data from its fraud data consortium – continue to stymie the development of a robust data-sharing layer for identity verification and fraud prevention.

Fortunately, as I have written about in the newsletter, a new generation of fraud data consortiums has emerged to help fill this gap.

Bringing It All Back Together

Banks and fintech companies’ increasing reliance on real-time transaction monitoring and step-authentication methods (like KBA questions!) to identify and stop fraud is a clear sign that the status quo for fraud management is not sustainable.

It’s simply not reasonable to expect to be able to effectively manage fraud without first having a strong set of controls in place for verifying and continually authenticating customers’ identities.

You can’t keep your stuff safe if you don’t know who’s walking through your front door.

I know it’s vastly more complicated to do that today than it was 30 years ago, but the financial services providers that thrive over the next 30 years will be those who figure out how to pull identity verification and fraud management back together.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Alloy.

Alloy is an identity risk management platform for companies that offer financial products. Beginning with origination and account opening, Alloy provides banks and fintechs with a scalable, flexible platform to manage identity risk throughout the customer lifecycle. Nearly 600 of the world’s largest banks and fintechs turn to Alloy to take control of fraud, credit, and compliance risk, and grow with the clearest picture of their customers.