19 January 2024 | FinTech

The Era of Financial Product Misuse May Finally Be Coming to an End

By Alex Johnson

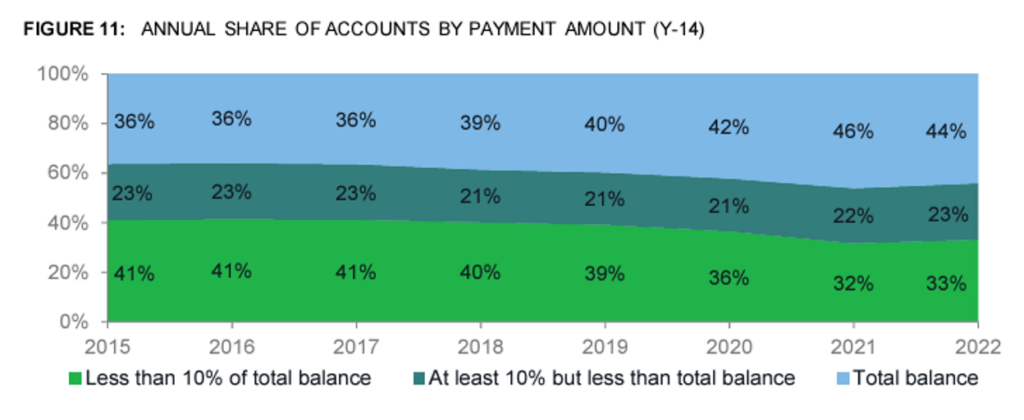

Here’s a bit of good news – according to the CFPB’s most recent biennial analysis of the consumer credit card market, the percentage of credit card customers who are fully paying off their monthly balances has been increasing steadily, up from 36% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. Conversely, the percentage of cardholders who are paying off less than 10% of their balances fell during that time, from 41% in 2015 to 33% in 2022.

In its report, the CFPB explains this unexpected development by pointing to the pandemic-era stimulus that many consumers received, which may have put them in a temporarily better financial situation.

While pandemic-era stimulus likely does account for the particularly sharp increase in consumers paying off their full balances in 2021, it does not explain why the five years before 2021 show a consistent shift in the mix of revolvers (those who carry a balance month-to-month) and transactors (those who pay their balances in full every month) in credit card issuers’ portfolios.

So, what explains this shift?

Here’s my theory – perhaps consumers have gotten a little better at using credit cards responsibly.

I know. I know. That answer feels unsatisfying and overly simplistic.

But I think part of the reason that it feels that way is because we’ve all grown accustomed to some deeply irrational behavior in the financial services industry.

The Rational and Irrational Uses of Financial Products

If you asked an alien who was visiting Earth for the first time to study the credit card – its function and essential properties – and explain to an 18-year-old human how they should rationally approach using the product, they would likely say something like, “Credit cards should be used, primarily, as a payment instrument, because of their ubiquitous merchant acceptance and robust fraud protections. The card’s credit line can give you immediate access to additional liquidity in emergencies, but you shouldn’t overspend on it habitually because of the comparatively high interest rate that it charges on revolving balances.”

The alien would most certainly not say, “Credit cards are like a loan, but you never really have to pay it all back, just the minimum or whatever on top of that you feel like. Don’t worry too much about it. Go out there and have some fun. YOLO.”

That would be a deeply irrational way to use a credit card, and yet, according to the CFPB, more than half of all credit card customers use them exactly like that.

This doesn’t make sense.

Sure, you’d expect that some percentage of consumers would be revolving a balance, at least sporadically, due to their individual choices and financial circumstances. But more than 50%? Really?

There’s obviously something else going on.

Cross-subsidization

Here’s a second thing that the alien wouldn’t say, “Credit cards are a payment instrument that you use, just like you would cash or a debit card, but with a sweet bonus – usage earns you hundreds, thousands, or even hundreds of thousands of dollars in free rewards a year, simply for using the product. How cool is that!?!”

This is not a rational expectation for how a credit card should work, either. And yet, it is exactly how they do work for the 40%+ of cardholders whom the CFPB designates as transactors.

This doesn’t make any sense!

How are credit cards able to simultaneously enable two different, deeply irrational behavioral profiles?

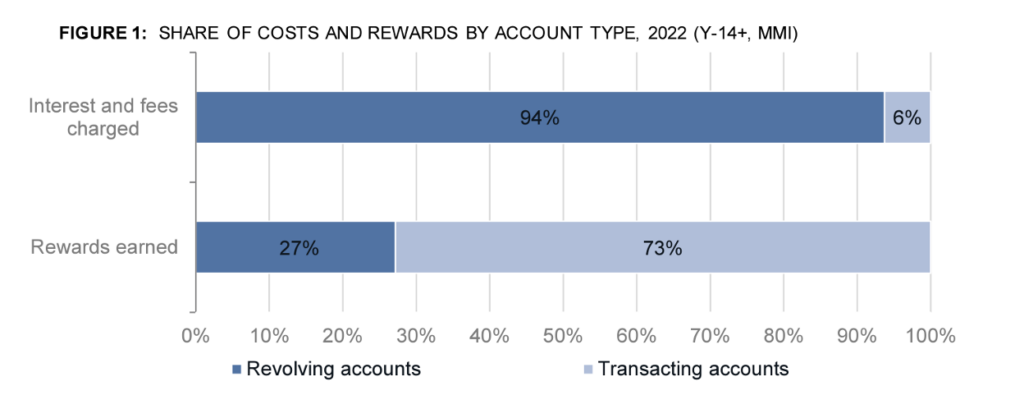

The answer, of course, is cross-subsidization. The revolvers’ irrationally bad use of credit cards pays for the irrationally great experience of the transactors. Check out this chart from the CFPB, showing the costs incurred and benefits earned by revolvers and transactors:

It’s difficult to appreciate – because this is the world we live in every day – but credit cards are truly an ouroboros of irrational product usage.

If everyone used the product rationally, the snake would just slither along normally. Instead, we have a majority of users irrationally misusing the product to their detriment, which funds the irrationally great experience of a subset of users, which acts as an advertisement for new users to come in and join the party.

And it’s not like credit cards are the only place in retail banking where we see this irrational product usage and complex cross-subsidization.

Let’s look at overdraft.

Overdraft protection, as a short-term liquidity tool, is not an inherently irrational product. When faced with a cash flow crunch, it’s not unreasonable to pay a $35 fee in order to avoid a large missed payment that might also come with some unpleasant side effects (like having your utility services disconnected or being evicted).

What is irrational is incurring overdraft fees on small, everyday transactions, which, according to research from the Financial Health Network, happens a lot. Indeed, in its 2023 FinHealth Spend Survey, the Financial Health Network found that 45% of overdrafters reported that their most recent overdraft occurred on a transaction of $50 or less.

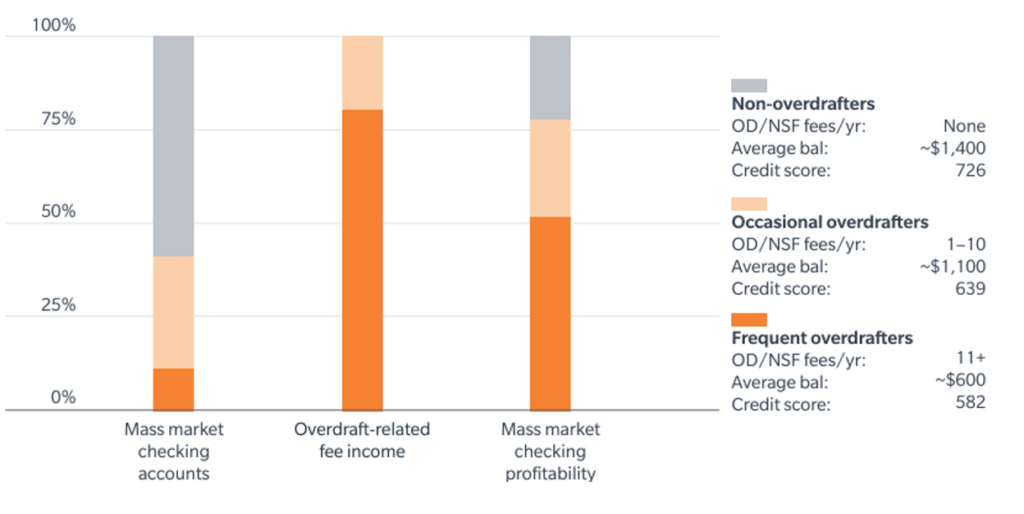

And like credit cards, the irrationality of overdraft isn’t a problem that is isolated to a small group of consumers making poor financial decisions. It’s part of a larger and precariously balanced system of cross-subsidization. According to a report from Oliver Wyman:

Frequent overdrafters represent only about 10 percent of mass-market consumers but generate more than 80 percent of all overdraft-related fee income. We estimate that these same consumers contribute more than 50 percent of mass-market checking account profitability, even after accounting for higher servicing costs, charge-offs, and churn. Frequent overdrafters effectively “pay for” the 60 percent of mass market account holders who do not generate enough in interest income or fees to cover their fully loaded cost.

I mean, look at this chart. This is insane!

In this case, we have a minority of users irrationally misusing the product to their detriment, which funds the irrationally great experience of the majority of users (free or low-cost checking!), which acts as an advertisement for new users to come in and join the party.

This doesn’t feel right, and I don’t think it’s sustainable.

When you put pressure on a system that relies so heavily on cross-subsidization, it can start to break down. When Congress capped interchange fees on debit card transactions for banks over $10 billion in assets (you’re welcome, retailers!), banks responded by increasing fees on checking accounts, a change that lower-income consumers and frequent overdrafters have borne the brunt of.

Fortunately, and as I alluded to at the beginning of this essay, we’re starting to see a little light at the end of this very dark tunnel.

The Benefits of Fintech Competition

Here’s another piece of good news from the CFPB’s credit card market report – consumer usage of credit cards’ built-in BNPL functionality is growing rapidly.

You may remember, in the halcyon days of ZIRP, a number of large credit card issuers reacted to the rising threat of BNPL by introducing BNPL financing functionality inside their card products, allowing customers to retroactively convert qualifying transactions (usually those over $100) into fixed installment plans.

I mocked this innovation when it first appeared. Why, I asked, would credit card users be interested in a less convenient and more expensive version of BNPL attached to their cards?

Wow, was I wrong!

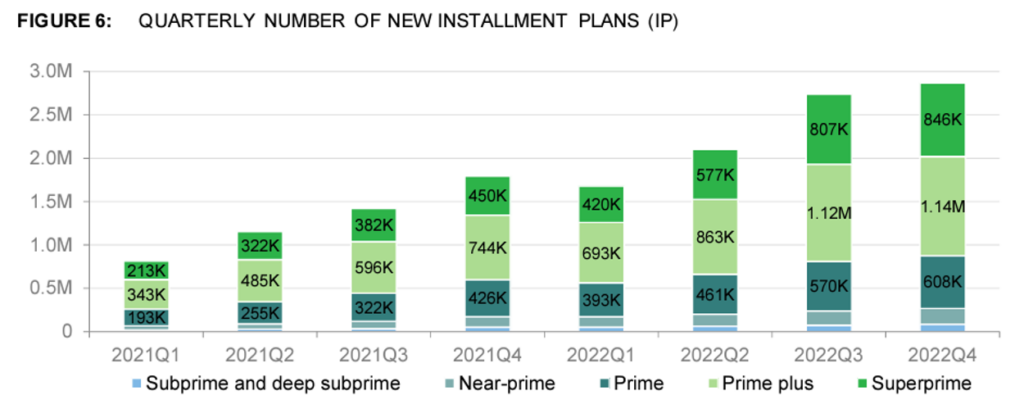

Turns out credit card users were very interested in this feature! According to the CFPB, the dollar amount covered by these installment plans more than doubled from 2021 to 2022, reaching $9 billion.

And it’s not just high-FICO, high-net-worth transactors who are using the feature to manage their cash flow on large purchases. The CFPB reports that half of the card-based installment plans in 2022 were for periods of less than six months, 37% were for 7-12 months, and 13% were for 13 months or longer. The average amount financed was $953. And growth in usage is consistent across the credit spectrum.

Why is this feature so popular?

I think the answer is, again, fairly simple – retroactive BNPL functionality makes it easier for consumers to use their credit cards rationally, as a payment instrument (primarily), and as a source of additional liquidity (where necessary).

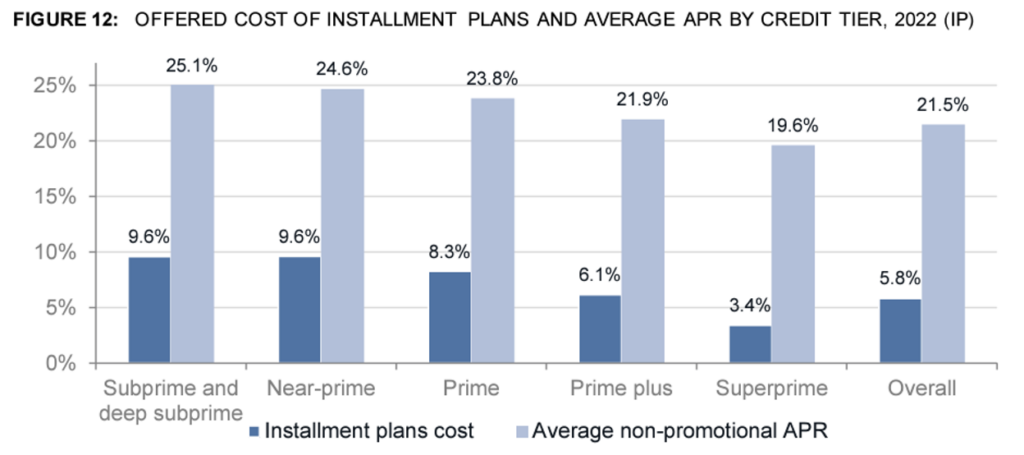

Cardholders are acting rationally! When they need to make a big purchase on their card, which they won’t be able to easily pay off by the end of the month, they are utilizing this BNPL feature rather than revolving a balance. They are doing this because, as the CFPB astutely notes, it’s less expensive to finance specific large purchases intentionally rather than to simply revolve one’s entire balance:

For all credit card users, from deep subprime to superprime, credit cards with built-in BNPL are a better product design than traditional credit cards.

This is the benefit of fintech companies competing with banks. They are pushing banks to build better, more rational versions of their products.

And fintech companies are continuing to push themselves as well!

Take Affirm’s new card product as an example.

The Affirm Card is a debit card with built-in BNPL functionality, which allows a user to finance a specific purchase before or after the transaction through the Affirm mobile app. The card, which was initially rolled out in Q2 of 2023, had already reached 500,000 active users and $100 million in monthly Gross merchandise value by October. Here’s how Affirm CEO Max Levchin describes the card’s appeal relative to traditional credit cards:

The credit card is, you swipe it, you revolve, you buy now and you pay for an indeterminate amount of time, possibly forever. Lots of people die with massive credit card debt to their name, and then their descendants have to deal with it. Affirm Card is a fixed-term loan for every transaction. There is no revolving, there is no bucket of debt to fill up and then figure out later. It’s a much simpler, higher control product. We think it’s the best alternative to credit cards.

It’s the same story with overdraft protection.

The emergence of neobanks, many of which offered free overdraft protection and two-day early access to paychecks, brought the problem of banks’ and credit unions’ excessive and predatory overdraft policies into sharp relief.

The resulting public pressure – from consumer advocates, regulators, and fintech companies – led to a significant voluntary change in many banks’ overdraft policies and fees over the last few years.

Unfortunately for them, it was too little too late, and the rock continued to roll down the mountain. This week, the CFPB proposed a rule to significantly curtail large banks’ overdraft programs. Here’s CFPB Director Rohit Chopra:

Decades ago, overdraft loans got special treatment to make it easier for banks to cover paper checks that were often sent through the mail. Today, we are proposing rules to close a longstanding loophole that allowed many large banks to transform overdraft into a massive junk fee harvesting machine.

The premise of the proposed rule is simple. If banks want to offer overdraft protection as a convenience for their customers (which is how overdraft first started), then they should have to price the service at cost. If banks want to offer overdraft protection as a short-term lending service and make a profit on it, then it must be regulated as a credit product, with all the attendant consumer disclosures and protections.

I absolutely love this rule. My only concern is that the CFPB is proposing that it only apply to financial institutions with over $10 billion in assets. This would be really stupid. As Aaron Klein has done a good job pointing out, community banks and credit unions are some of the worst offenders when it comes to excessive or predatory overdraft programs. The CFPB’s final rule should include all financial institutions, not just the biggest ones.

What’s Next?

I think fintech has helped usher in the end of the era of financial product misuse.

The natural incentive for banks to grow and to construct increasingly complex cross-subsidization systems within their customer portfolios is being counterbalanced by the incentive to compete with fintech companies to deliver the most value to each individual customer (and to demonstrate that value delivery publicly to regulators and lawmakers).

In the short term, the result of this trend will be continued disruption in established financial product categories, such as tax filing (why should consumers with straightforward tax situations pay any money at all to file their taxes?) and merchant loyalty programs (stop profiting from breakage!)

In the long term, the result of this trend will be that the more wealthy and financially savvy segments of financial services consumers (including me!) will need to come to grips with the disappearance or reduction of certain perquisites (rewards, free products and services, etc.) to which we’ve become accustomed.