05 January 2024 | FinTech

1033: Letters From the Front Lines

By Alex Johnson

When the CFPB released its proposed personal financial data rights rule (AKA open banking) back in October, there was a lot of grumbling in the industry.

No one – banks, fintech companies, data aggregators, merchants, big tech companies – was perfectly happy (which, incidentally, is a good indicator that the bureau wrote a rule that is fair and balanced).

One group of people was particularly grumpy, though – the lawyers and policy folks who were going to need to draft up their comment letters to the CFPB before the bureau’s unusually short deadline – December 29, 2023.

These folks had a stressful holiday season.

But they got it done! Comments were submitted. More than 11,0000 of them.

As the CFPB embarks on the process of digesting these comments and finalizing the rule, I thought it would be useful to read through some of the comments myself to try to get a sense of where the points of contention are in open banking these days.

Before I get into that, though, a few quick notes:

- I didn’t read all 11,000 comments, obviously. I focused on a small subset of comments from authoritative sources representing the primary constituencies in open banking – big banks, small banks and credit unions, data aggregators, fintech companies, merchants, trade associations, and public policy groups.

- The proposed rule from the CFPB identifies three primary stakeholders – data providers (companies that possess data covered by the rule and that must be shared at their customers’ request … this group is mostly banks and credit unions), third parties (companies that receive consumers’ data with their permission … today, this group is mostly fintech companies), and data aggregators (companies that assist third parties in connecting to and retrieving data from the data providers … this is where Plaid, MX, Finicity, and many others fit). The arguments for and against different parts of the proposed rule can generally be organized into these same three groups.

- A large chunk of the 11,000 comments were letters from individual consumers asking the CFPB to include electronic benefit transfer (EBT) accounts in the final rule. This was clearly the result of an influence campaign by some fintech company or trade association. It came across as a bit hamfisted to me, but points for trying, I suppose.

- Many of the arguments made in the various comments were focused on the legal authority of the CFPB as it relates to various points within the proposed rule. I am choosing to ignore these arguments because they are stupid. I understand that lawyers gotta lawyer, but come on. Director Chopra isn’t going to read one of these comments and say to himself, “You know what? I am overstepping my legal authority here. I’ve changed my mind.”

- There seemed to be substantial (though not universal) agreement from commenters across all stakeholder groups that the proposed implementation timelines following the publication of the final rule are too aggressive and need to be extended. Multiple commenters also urged the CFPB to designate an approved standard setting organization (SSO) as quickly as possible so that data providers will have a defined technical specification that they can build to.

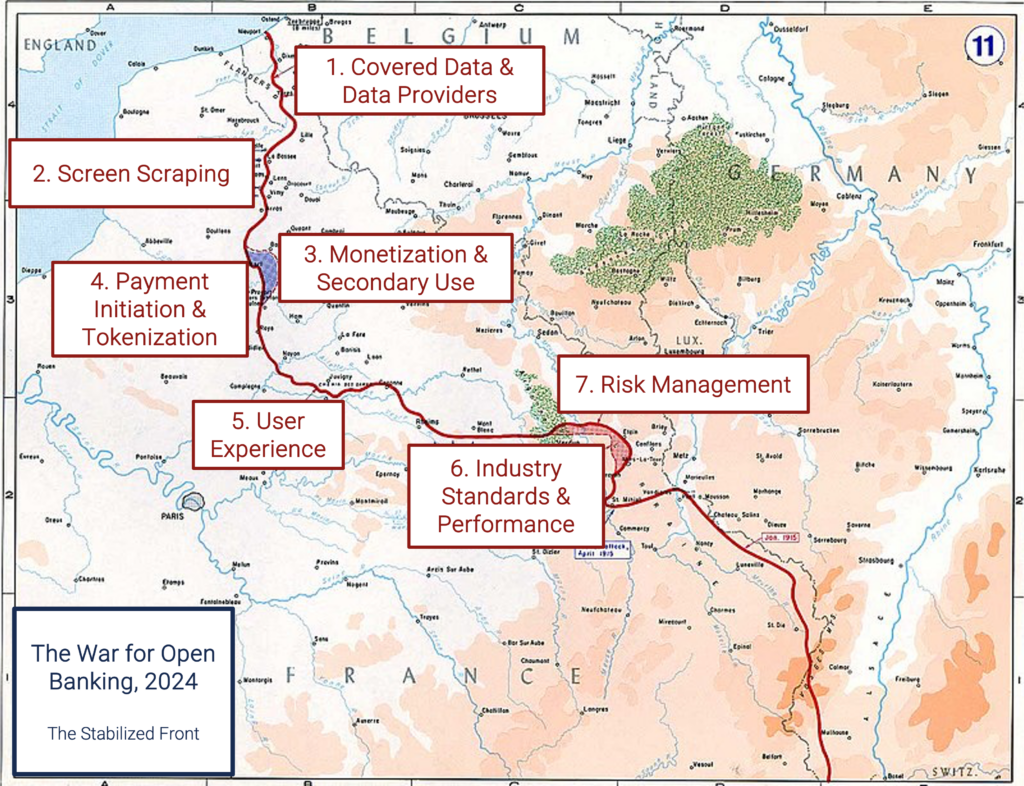

OK. With that out of the way, let’s take a tour through the various fronts in the war for open banking. I’ll provide a little bit of my own personal commentary on the issues as we go.

1. Covered Data & Data Providers

The CFPB’s proposed rule covers Regulation E accounts (deposit accounts), Regulation Z accounts (credit cards), and products or services that facilitate payments from a Regulation E account or a Regulation Z credit card (digital wallets).

There was actually quite a bit of agreement across the comments I read that the CFPB should consider adding additional data and account types to the rule. Chime, for instance, argued that the rule should include payroll data (a suggestion that payroll API providers like Atomic and Pinwheel strongly argued for as well) and small-dollar liquidity products such as cash advances, payday loans, and BNPL. This general sentiment was shared by banks and bank trade associations like the Consumer Bankers Association as well as the big data aggregators (MX, Plaid, etc.)

Where there was more disagreement was on the scope of the data that was required to be shared under these different data and account types.

The CFPB’s proposed rule covers quite a bit – transaction information, account balance, information to initiate payment to or from a Regulation E account (we’ll revisit this one in a minute), terms and conditions, upcoming bill information, and basic account verification information.

As you’d probably guess, banks had some suggestions for narrowing this scope, particularly as it relates to the terms and conditions (which includes pricing and rewards, which are sensitive areas, particularly for credit card issuers) and upcoming bill information (which they argue is unverified and potentially concerning from a data privacy perspective).

Fintech companies, on the other hand, were all for sharing, and they encouraged the CFPB to be as expansive as possible in their definitions of what “covered data” includes. Here’s Plaid:

The Bureau should consider listing more examples of covered data, or providing more expansive language, to ensure that the listed data fields are not narrowly interpreted by data providers in a way that limits consumer access. For example, when a consumer wants to access and share their account balance, they should also know whether that balance number is in dollars, pounds, or euros;

Alex’s Two Cents: I agree with the consensus that the CFPB is making a mistake by limiting the rule to deposit accounts, credit cards, and digital wallets while excluding payroll data, BNPL, installment loans, investment accounts, and other product categories. The CFPB has said that it will address other product areas with additional rulemaking in the future, but with an election looming later this year, that is far from certain.

When it comes to the scope of the covered data within these categories, I tend to side with the fintech argument that more data is better. Banks’ counterarguments – cost to comply, concerns over sharing proprietary data, etc. – aren’t especially persuasive to me.

2. Screen Scraping

None of the comment letters that I read argued that screen scraping is a good solution for consumer-permissioned data sharing. However, there was some disagreement between banks and data aggregators on how quickly and forcefully screen scraping should be phased out in favor of APIs.

The banks argued that the final rule should prohibit third parties and data aggregators from using screen scraping to acquire any covered data if that data is available through a compliant API and give banks permission to block those that try to screen scrape in violation of this requirement. Here’s how PNC frames the argument:

Data providers should not be required to invest in creating a developer interface without a concomitant responsibility of third parties and data aggregators to use that interface. If the Bureau mandates that data providers maintain a method to allow customer data sharing to occur in a more secure and permissioned fashion, then third parties and data aggregators should be required to use that method so that these objectives are achieved. They should not have the option to bypass a secure developer interface in favor of screen scraping.

The data aggregators were careful not to appear in favor of screen scraping (or “legacy connection methods,” as one commenter artfully put it) while arguing for the continued use of screen scraping during the final rule’s implementation period and as a backup when APIs go down or undergo maintenance.

Alex’s Two Cents: I’m sympathetic to the bank argument here. If you build an API that is compliant with the final rule’s requirements, you shouldn’t have to worry about screen scraping. I’d be in favor of allowing screen scraping during the final rule’s transition period (to ensure no consumer loses the ability to share their data) and then a ban on the practice once the APIs are up and running.

One problem – what do we do for the non-covered data (payroll, loans, investment accounts, etc.) that many consumers are currently sharing through aggregators (which are using a combination of APIs and screen scraping to get)? This is another reason why adding more product types to the final rule would be a good idea!

3. Monetization & Secondary Use

The CFPB’s proposed rule would restrict data providers from charging a fee to provide their customers’ data while placing no such restriction on data aggregators. This strikes banks as deeply unfair. Here’s JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank by market cap in the world, whining about it:

Data aggregators charge fees to third parties for enabling data access and for products derived from that data access, profiting from data providers’ infrastructure and security investments. If data aggregators are permitted to charge fees to authorized third parties, there is no reason data providers should not likewise be permitted to charge reasonable fees.

The banks argue that a “reasonable” fee is fair and necessary compensation for the work they are required to do to set up and maintain compliant APIs for data access.

This is especially important to the banks if the CFPB decides to loosen up the requirement in the proposed rule restricting data aggregators and third parties from leveraging the customers’ data for “secondary use”.

What is secondary use? Glad you asked!

The CFPB’s proposed rule includes a blanket prohibition on third parties processing covered data for secondary purposes – i.e., any collection or use beyond what it is “reasonably necessary” to deliver the product or service requested by the consumer. This includes selling the data to other parties (an obvious no-no), marketing or cross-selling additional products, and R&D for future product development. This prohibition would apply even if the data was de-identified.

Banks, which are deeply annoyed by the notion of building infrastructure for their competitors to freely use, pushed very hard in their comments to maintain or even strengthen these prohibitions on secondary use.

Fintech companies pushed back in their comments, arguing that most data privacy laws (including the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, which banks are subject to) do not go nearly as far as the CFPB’s proposed prohibition on secondary use but rather rely on disclosures and consumer opt-in/opt-out mechanisms to govern secondary use. They also strongly disagreed with banks on de-identified data, arguing that, by its very nature, de-identified data presents no risks to consumers and should be permitted for secondary uses like product development.

Alex’s Two Cents: I don’t think that banks (or the service providers like Akoya that they work with to deploy their APIs) should be able to charge third parties or data aggregators for access to customer data. I’m also fine with third parties and aggregators being able to leverage the data for secondary uses (except for selling the data) with appropriate disclosures and out-outs.

A good parallel here is the credit bureaus. Banks furnish data to the credit bureaus for free and then pay the credit bureaus to get back credit files, attributes, and scores. Those attributes and scores (and plenty of other products and services) are built through secondary uses of the data (both identified and de-identified). The same general approach should be applied in open banking.

4. Payment Initiation & Tokenization

As I mentioned earlier, one of the data elements that data providers are required to share under the proposed rule is information to initiate payment to or from a Reg E (deposit) account. If it makes it into the final rule, this particular requirement would help accelerate the growth of pay-by-bank solutions in the U.S.

This notion TERRIFIES banks, particularly the big credit card issuers like JPMC. Here’s a quote from Chase’s comment letter, basically doing the same thing that I do with my kids when I don’t want them to do something but can’t articulate a specific and rational reason:

The payments ecosystem is complex with significant nuances across networks, types of transactions and constituents. The CFPB’s proposal ventures into regulating the payments ecosystem without proper consideration of the costs, interactions among participants, and significant risks this proposal would create. Requiring the sharing of payment initiation information will be a catalyst for significant growth of “pay-by-bank” models, a payment method that is ill suited, yet is increasingly being adopted, for many types of transactions like eCommerce purchases. The CFPB should drop the requirement to enable payments from the final rule and take steps to separately consider these complexities and nuances before embarking on regulating the payments space through its section 1033 rulemaking.

IT’S COMPLEX AND YOU HAVEN’T THOUGHT THIS THROUGH AND YOU REALLY SHOULDN’T DO THIS THING JUST TRUST ME.

In banks’ ideal world, the CFPB would drop the requirement to support payment initiation data from the final rule and kill the idea of pay-by-bank before it can grow up and become a real threat.

This seems unlikely to happen, but banks and bank trade associations and consortiums may end up getting a consolation prize – tokenized account numbers (TANs).

The basic idea of a TAN, similar to the tokens that are used in the world of card payments, is to replace sensitive account and routing numbers with dynamically generated substitutes that can be used (and managed) on a case-by-case basis.

Sounds very reasonable, and the basic logic – don’t share sensitive information all over the place! – is sound. And the CFPB seems to agree. Its proposed rule is generally supportive of allowing data providers to use TANs in place of account and routing numbers.

However, fintech companies, data aggregators, and merchants (which all like pay-by-bank) have some concerns. They argue that:

- TANs actually enable fraud. They do this in two ways. First, TANs make it much more difficult for payment processors and merchants to link together a consumer’s various transactions (because there is no account number to use as a unique identifier) in order to understand the risks that they pose. This is bad for legitimate customers, as they are less likely to get the benefit of the doubt, and good for fraudsters which can use and then revoke TANs in order to game the ACH debit settlement delay and steal from merchants. In its comment letter, Trustly (which enables a lot of pay-by-bank volume today) shared some compelling evidence of this fraudulent misuse of TANs.

- TANs are not interoperable. In comparison to the card networks, the world of Reg E payments is very fragmented. This poses an interoperability challenge – if each bank builds its own tokenization service for account and routing numbers, it becomes extraordinarily complex for payment processors and merchants to facilitate payment transactions using TANs. And even if a centralized group like The Clearing House provides the tokenization service (which is something that TCH is already doing for a lot of banks), there’s no guarantee that the resulting TANs will be compatible with every underlying payment rail that a Reg E account could transact through (FedNow, for example, isn’t supported by TCH TANs).

- Banks and bank consortiums may use TANs to block competitors. Tokenization can be misused by market incumbents. In the payment card world, Mastercard got into some trouble recently with the FTC, which alleged that the network had illegally used its tokenization service to block merchants from routing transactions to less expensive, non-Mastercard networks.

Alex’s Two Cents: I would be surprised and disappointed if the CFPB removed the requirement to provide payment initiation information from the final rule. The whole point of 1033 (in the mind of Director Chopra) is to encourage competition. Pay-by-bank may end up being the most significant competitive threat enabled by open banking when all is said and done.

On the subject of TANs, I’m a bit more ambivalent. If they can be implemented in a way that is interoperable, supportive of all underlying payment rails (especially those not controlled by TCH), and fraud-resistant (i.e. paired with some other unique identifier), then I suppose I’m cool with it.

5. User Experience

This is the “Please, Mom and Dad, don’t fight in front of the kids” fight.

The central question at issue is which party should be responsible for capturing the initial authorization from the consumer to share their data and which party should be responsible for authenticating (and re-authenticating) specific data-sharing requests from the consumer.

In its proposed rule, the CFPB suggested that third parties should be the ones to capture the initial authorization, but the data providers should be able to directly authenticate the consumer.

Neither banks nor data aggregators seem particularly happy with this proposal.

The banks argued that both the initial authorization and all authentications should happen directly through them in order to maximize transparency and safety for the consumer.

The data aggregators, shockingly, disagreed. They supported the proposal that third parties should be solely responsible for authorization and made the case that data providers should be extremely constrained in how they authenticate the consumer. Their concern on the authentication front is that, if presented with the opportunity, many banks will choose to inject friction into the authorization user experience, which negatively impacts conversion. In its comment letter, Trustly shared that they’ve seen this behavior firsthand:

Over the past few years, Trustly and other market participants have shifted to API connections hosted by data provider banks. This transition has involved banks injecting a number of their own user experience screens into the open banking onboarding process. Our observation is that these screens are generally duplicative of Trustly’s own onboarding process, and often incorrectly overstate the information that may be shared with Trustly and our merchants.

Alex’s Two Cents: I think the CFPB landed in the right place in its proposed rule (banks and fintechs were both disappointed! That’s a good sign!) Data providers shouldn’t be involved in the authorization process. The consumer is working with a third party to get a product, service, or experience that requires their bank data. It makes sense for the third party to capture their consent and share the appropriate disclosures with them. And I think as long as the CFPB ensures that banks don’t play games in the authentication process (and encourages the adoption of app-to-app and biometric authentication technology where possible), it makes sense for data providers to be directly involved. Speaking as a consumer, that’s what I want.

6. Industry Standards & Performance

Everyone in the ecosystem seems to agree with the CFPB on the need for an independent SSO to define and maintain the required technical standards. And while the CFPB hasn’t officially taken this step yet, it’s highly likely that they will officially bless the Financial Data Exchange (FDX) as the chosen SSO at some point (ideally sooner rather than later).

In its proposed rule, the CFPB did offer some fairly specific thoughts on what a good SSO – one that the bureau would officially recognize – would look like. This appears to be the CFPB’s attempt to gently nudge FDX into making some changes in regard to the balance of influence over decision-making between banks and fintechs. This received some mild pushback from the Consumer Bankers Association (CBA) in its comment letter.

There was significantly more disagreement when it came to the proposed performance requirements for data providers’ APIs.

The CFPB’s initial proposal suggested a minimum uptime of 99.5% and a maximum transaction response rate of 3.5 seconds.

Neither banks nor data aggregators found these proposed performance requirements acceptable.

Banks argued that it would be expensive, technically difficult, and unfair given that the CFPB isn’t planning to impose any significant limitations on third-party access or allow data providers to charge fees to recoup their costs.

Data aggregators argued that these requirements were much too lax compared to the commercial expectations that API providers in other markets are held to, with Plaid stating in its comment that the CFPB “should be cautious about giving financial service companies regulatory permission to have perpetually slower technology than the rest of the economy.”

Alex’s Two Cents: The SSO is absolutely going to be FDX, and my personal opinion is that the current imbalance in decision-making influence between banks and fintechs within FDX is largely the result of fintech companies choosing not to directly participate but rather to let Plaid, MX, and Finicity represent their interests. Time to get involved, guys!

On the performance requirements, I think 99.5% uptime is a bit low for the big banks. Perhaps the CFPB could have different floors for different-sized data providers? And on the latency question, I thought Trustly had a good idea – define more specific requirements for different API endpoints. If it genuinely takes longer to return transaction details through the API than it does customer identity variables, then the minimum latency requirements should be different!

Finally, on the topic of standards, I thought this suggestion from Akoya was pretty interesting:

We believe that the CFPB should do more to facilitate the ability of an authorized third party to switch data aggregators. Currently, data aggregators use proprietary APIs to interface with authorized third parties, which may require bespoke connections from authorized third parties. This makes changing data aggregators difficult for authorized third parties, because of the additional technical resources required to connect to a new data aggregator’s API. The CFPB should require uniform standards for the connections between data aggregators and authorized third parties, as defined by an SSB. This would lower the cost of authorized third parties to change from one data aggregator to another, and thereby drive business to the most competitive data aggregators, all to the ultimate benefit of consumers.

This wouldn’t be great for the data aggregators, obviously, but it would increase competition (which is the CFPB’s primary goal with 1033), and it would make fintech companies’ lives more pleasant (this is why you get involved in standards setting!)

7. Risk Management

I left the stickiest wicket for last.

It boils down to this question – to what extent should banks be permitted to slow down or stop consumer-permissioned data sharing in response to risk management concerns?

The core issue here is that banks have two different sets of regulators to answer to – regulators that care about protecting consumers (CFPB, FTC, state attorneys general, etc.) and prudential regulators that care about maintaining the safety and soundness of the U.S. financial system (OCC, FDIC, Federal Reserve, etc.)

The CFPB is the one writing this rule. They are writing it in order to maximize the benefits of competition and portability for consumers. They are, generally speaking, in favor of forcing banks to take risks to help consumers.

The OCC, FDIC, and Fed recently released updated guidance for banks on how to deal with the risks associated with working with third parties (I wrote about it a bit here). They wrote it in order to maximize the safety and soundness of the financial system. They are, generally speaking, not in favor of forcing banks to take risks to help consumers.

You can see the problem.

In response to the CFPB’s proposed rule, which suggested giving data providers some narrowly defined options for not sharing data with third parties due to risk management concerns, banks asked for more latitude. Here’s what the CBA wrote:

The Bureau should revise proposed section 1033.321(a) to specify that a bank denying a third party access to a developer interface based on guidance issued by prudential regulators with respect to third party risk management is a reasonable denial. This approach would ensure that all data providers are able to protect the safety and soundness of the financial system as a whole. While the Section 1033 final rule will facilitate greater access by third parties to covered data held by data providers, access cannot come at the expense of a stable and secure financial ecosystem.

Compelling!

But on the other side, data aggregators argue that allowing data providers to deny access based on risk management concerns will give banks a very broad pretext to prevent startups, many of which they directly compete with, from getting the data they need to deliver value to consumers. Here’s how Plaid put it:

Data providers will construe [the rule] as giving them discretion to grant or deny access based on purported “risk management concerns.” This means that thousands of data providers, which are already inherently conflicted by the fact that they are competing with third parties for business, will apply thousands of different risk management standards in determining whether to grant or deny access.

Also very compelling!

Alex’s Two Cents: Ironically, both banks and data aggregators ended up asking for the same thing in response to this risk management problem – for the CFPB to directly supervise, regulate, and certify all the third parties that want to access consumer bank data.

The CFPB does not want to take on that responsibility, but I don’t see a lot of other great options.