14 October 2023 | Climate Tech

Hubba hubba

By

In perhaps the biggest news of the week, the Biden Administration and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations unveiled $7B in funding for seven different regional hydrogen “hubs” to scale up the production of green hydrogen in the U.S. This is the single largest government commitment to spur green hydrogen production we’ve seen, and will allocate funds to a wide range of companies and organizations across the different hubs. Examples of selected hubs are as follows:

- The Appalachian Hub: Combines efforts across West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania. The approach here will hinge on carbon capture. Hydrogen will be produced more ‘traditionally’ through steam-methane reforming, tapping into the vast natural gas resources of this region. Carbon capture devices will be deployed to absorb the emissions from the production.

- The Midwest Hub: This hub will combine efforts from a diverse group of stakeholders in Michigan. The production method here will focus on using renewables (the Midwest has lots of wind), natural gas (with carbon capture, as above), and nuclear (there are reactors in Chicago, for instance, and the Palisades Plant in Michigan may reopen).

- The California Hub: This hub would rely on California’s ample solar resources and use produced hydrogen to help decarbonize heavy trucking and port operations.

You can explore the rest of the selected hubs and the companies benefitting from government funding here.

The DOE hopes the regional hubs will eventually generate 3M metric tons of hydrogen annually. Globally, around 75M metric tonnes of H2 is produced as pure hydrogen, and an additional 45M metric tonnes is produced of a mix of gasses. If we take the 75M number for pure H2 and remind ourselves that only 1% of global hydrogen production is green, that means that less than 1M metric tonnes produced globally in any year are ‘green.’

Hence, fundamentally, the DOE’s 3M tonne annual production target for the Hydrogen Hubs program is an attempt to triple or quadruple the current amount of global green hydrogen production. In the U.S. alone. No small ambition! Not to mention a 50M metric tons of clean hydrogen fuel target (!!!) out to 2050. We’ll discuss some of these proposed targets and scales further a bit later on.

A diversity of approaches, a diversity of uses

As evidenced by the selections offered above, many different methods of producing green hydrogen are being tested here. That’s part of DOE’s goal in diversifying where it allocated resources. The beauty of this program is there’s now a diverse (both in geography and approach) set of tests that will explore how to produce green hydrogen at scale and as efficiently as possible.

- ‘Firm’ power: Is the best way to support electrolysis with dedicated energy generation sources, like nuclear, that are ‘always-on’?

- Renewables: Can you produce hydrogen with otherwise stranded renewable energy capacity, e.g., curtailed wind and solar? Or does that kill the economics of the project?

- Carbon capture? How close to 100% can those employing carbon capture get when trying to capture the emissions from ‘traditional’ team-methane reforming? Is there sufficient storage for the captured carbon?

On the demand side, i.e., who the buyers are and what the end uses for green hydrogen are, there are also many contenders (not that they’re necessarily competitive).

- Industry: Hydrogen is already widely used in chemical and fertilizer production. That demand and need isn’t going anywhere. It will grow as the world does. Similarly, hydrogen could be used in fundamentally new industrial applications where it hasn’t been previously, such as in cement and steel production, to achieve incremental emissions reductions by displacing some coal and natural gas use.

- Transportation: You can power anything from ships to consumer cars with hydrogen. Even though most folks at this point have moved past the idea of the hydrogen-fired consumer car, hydrogen could still be hugely relevant in heavier transport, whether trucking or shipping, for instance. As an example, in China this week, a hydrogen-powered vessel made its maiden voyage from Yichang City in the Hubei Province. The boat is powered by a 500kW hydrogen fuel cell with a maximum range of 200 kilometers.

- Energy generation: Hydrogen can be used in fuel cells to generate electricity for a wide range of applications, from small devices to large power plants. Hydrogen co-firing in natural gas plants and coal plants is possible. It’s already happening.

- Energy Storage: Hydrogen can be used for energy storage. Excess electricity from renewables can be turned into hydrogen through electrolysis, and the hydrogen can then be stored for later conversion back into electricity. As I’ve often mentioned, there’s a large energy loss in the round-trip efficiency of this process, so it may not be the best application.

Adam Goff, SVP of Strategy at 8 Rivers, synthesized some of the questions posed here elegantly in a podcast episode we recently recorded:

Hydrogen is the lightest molecule we have, right? It’s a really exciting potential energy carrier and fuel source for the future. If you use hydrogen as a direct fuel… it’ll burn; it’ll burn really hot. And there’s no carbon. That’s why people have been really entranced with hydrogen for a long time.

That said, the challenges around hydrogen include that it is a pain in the butt to deal with. It is extremely expensive to handle. It likes to escape. It’s hard to compress.

I think one of the big questions in hydrogen is, what’s it for? That’s what the industry and policymakers are trying to figure out. Where do we use it? Where do we not use it? If I were a betting man, I would bet on, first-off, existing uses. These are the things we know we need it for. Fertilizer is important, as is refining. We use hydrogen to make jet fuels and refine liquid fuels. We use it to make fertilizer to grow food for people to eat.

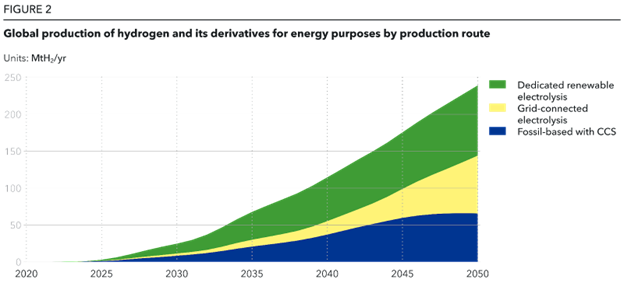

Unifying all the potential use cases, the below graphic represents what the scope of the decarbonization-driven scale-up in demand for green hydrogen could look like. Today, very little hydrogen is produced in a low-emissions manner. But by 2050, there could be a massive market for green hydrogen. DNV anticipates green hydrogen will grow to become a $6.8 trillion market by 2050 and that green production will approach 250M metric tonnes annually (visualized below).

Remember, current global hydrogen production is 75M metric tonnes annually. Again, similar to the DOE’s desire to produce 3M metric tonnes of hydrogen domestically, DMV’s forecast represents another tripling, this time of global hydrogen production in general. If we assume that tripling can happen and it will all be green, we’re basically in dreamland. I’m not saying it isn’t possible, but as always, take these future forecasts with many grains of salt.

If the market does grow as DNV predicts, that would mean that many, if not most, of hydrogen’s potential use cases we outlined became significant sources of demand. Tying it back to the present day, the possibility of that supply-side scale-up also needs to start now. Which depends on how the rest of the U.S. and other countries’ policies support mechanisms coalesce, beyond funding dollars.

From dreamland, back to 2023

While the allocation of $7B in DOE funding is a significant step, there’s a lot still up in the air on the hydrogen front. For one, the government will roll out more funding in the coming years. It might not necessarily go to the same parties that were granted funds in this initial round. As Emily Pontecorvo also helpfully summarized in a recent Heatmap piece:

“I think it’s important to emphasize that what DOE is announcing is an invitation to negotiate potential funding awards,”Jill Tauber, the vice president of climate and energy at Earthjustice, told me. “So this is not an announcement of final decisions and awards. There are still approvals to be secured.”

Funding from other government organizations may also supplement recipients of DOE funding.

Further, another central area to watch is precisely what the clean hydrogen tax credit, a subsidy from the Inflation Reduction Act, ends up looking like. Under what conditions will hydrogen production qualify for it? That is an area of intense, highly nuanced debate.

Finally, capital allocated by the government also doesn’t magically translate into any of the green hydrogen production numbers thrown around in this piece. Project proposals need to be designed, reviewed, and then put into motion. Then, infrastructure needs to get built. And buyers of green hydrogen need to actually show up and back up the demand they’ve signaled they’ll offer.

There are more questions than answers to how the hydrogen hubs, industry development, and policymaker standard-setting will progress. But as with so much of climate tech, this is a story that’s in its complete infancy. It’s a story of many actors trying to find the right ways to make what’s gone right for solar and EVs happen elsewhere.

The net-net

I do not know whether these hub programs, whether for hydrogen or DAC, will succeed. Down the line, we may look at them and see stranded assets, reminders of failed experiments. We may, literally and figuratively, see climate tech ghost towns. Or they could catalyze trillion-dollar industries.

The absence of any prediction from me may feel dissatisfying to you as a reader here. We crave clarity, both as individuals and as members of various organizations with concrete goals. Companies and project developers do require clarity on many things to do their work.

And our desire for clarity – which is natural, normal, and not something I’m maligning – can create a lot of discomfort when it inevitably chafes against the increasingly complex world we live in. That can drive an impulse to disengage, to write things off, to turn elsewhere. I see that in the hydrogen conversation. Many people bow out. Because it is complex. Is confusing. Is messy.

The invitation I offer as a counter is simple. When that urge to disengage arises, pause. That discomfort, inherent to ambiguity, doesn’t have to yield ambivalence. Or abandonment. The fundamental opportunity at hand is engagement. Namely, to shape a new green hydrogen industry!