25 March 2023 | Healthcare

How The Affordable Care Act Ruined Physician-owned Hospitals

By workweek

The Affordable Care Act celebrated its 13th birthday—mazel tov.

It hasn’t been the easiest 13 years, though (my parents also said this to me when I turned 13). The ACA has battled countless lawsuits over the individual and contraception mandates and faced tremendous controversy regarding the actual “affordability” of ACA Marketplace insurance plans.

Now, another controversial part of the ACA is resurfacing: the effective ban on physician-owned hospitals (POHs).

So, to celebrate the ACA’s birthday, I’ll discuss the history of POHs, explain how and why the ACA ruined them, and then offer my $0.02 on the issue.

The History of Physician-owned Hospitals

POHs started popping up in the 1980s in response to managed care and the ever-so-increasing corporatization of healthcare delivery. Physicians value autonomy. But, managed care and the corporatization of medicine were removing that valued autonomy. To combat the imminent loss of autonomy, physicians started creating POHs where they would have control and ownership over patient care.

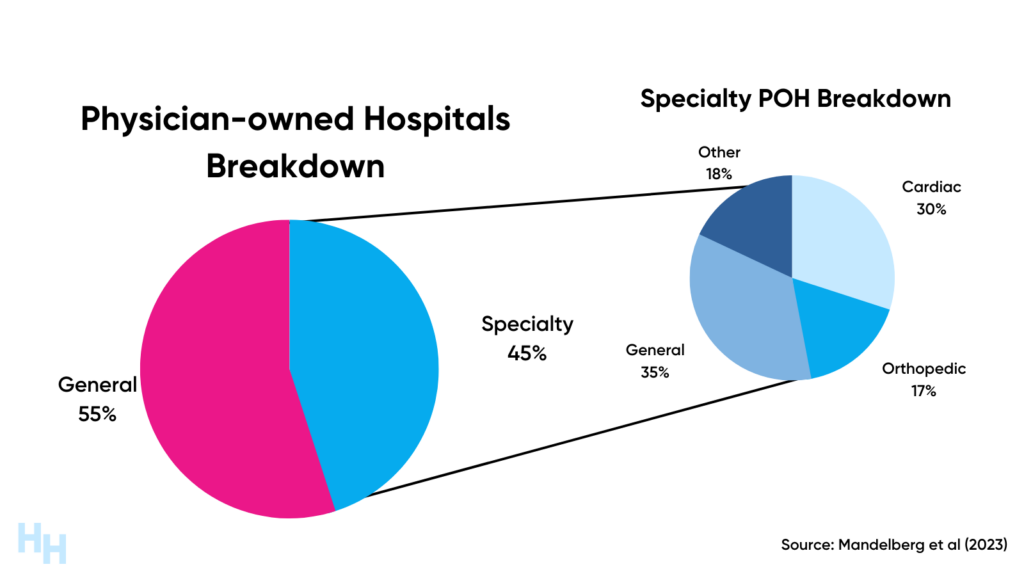

By the early 2000s, there were around 65 POHs among the thousand-plus non-POHs. These POHs fell into two categories: general POH and specialty POH.

- General POHs were akin to your local community hospital, offering a broad range of services.

- Specialty POHs mainly focus on one medical area, such as cardiac care or orthopedic care. However, there are specialty hospitals that are general surgery.

By 2010, there were around 265 POHs among the 6,000+ non-POHs—a mere 4% of all U.S. hospitals. The growth to 265 POHs was an uphill battle.

Incumbent hospitals felt threatened by POHs in the early 2000s and wanted to prevent their market entry. Lobbying efforts from hospital organizations like the American Hospital Association (AHA) and Federation of American Hospitals (FAH) led to congress and other federal agencies investigating POHs to study referral patterns, quality of care, costs, share of uncompensated care, and other outcomes.

As a result, in 2003, Congress implemented a temporary 18-month “freeze” on the expansion of physician-owned hospitals by forbidding doctors from directing their patients to specialty hospitals in which they had a financial interest. The objective of Congress was to utilize this 18-month interval to investigate the potential negative impact of POHs on non-POHs.

During the study period, there were a few antitrust lawsuits filed against non-physician-owned hospitals. These hospitals were accused of colluding with other local non-POHs to prevent primary care referrals to POHs and teaming up with insurance companies to exclude POHs from their networks. Humana, which was a party to the Heartland Surgical Specialty Hospital lawsuit in Kansas City, stated:

[the] major [health] systems… view [POHs] as direct competitors… and are placing intense pressure on carriers not to contract with these entities.

Several studies from the government evaluating POHs compared to non-POHs found the following:

- No evidence of negative financial impact on local community hospitals.

- Patient severity was lower at some cardiac specialty hospitals.

- Patient satisfaction, quality of care, and efficiency were superior at POHs.

Despite these results, lobbying efforts from AHA and FAH picked up, arguing that POHs cherry-pick their patients and create physician-induced demand leading to “intolerable risk [and] irreparable harm].”

The Pompeii of Hospitals

AHA and FAH’s lobbying succeeded as section 6001 of the Affordable Care Act banned new POHs and their expansion.

And yes, this was all from lobbying efforts.

Chip Kahn, President and CEO of FAH, admitted, “the current ban on physician-owned hospitals wouldn’t be there if it wasn’t for the Federation… I can remember emailing one of the staffers, literally sending in talking points to some of the senators as the process was taking place.”

You can’t make this up.

Section 6001 didn’t explicitly state that POHs were prohibited, but instead utilized the Stark Laws and the “whole hospital exemption” to effectively ban POHs.

- Stark Laws: prohibit physician self-referral in Medicare and Medicaid programs.

- Whole Hospital Exemption: allows physician self-referral in Medicare and Medicaid programs if physician’s ownership was in a whole hospital facility (e.g. POH).

Section 6001 of the ACA removed the whole hospital exemption for POHs, exposing them to Stark Laws. This means POHs wouldn’t receive reimbursement or funding from Medicare or Medicaid, which are essential for financial viability. Without such reimbursement or funding, hospitals fail.

But what about established POHs before the ACA was enacted? They’ll still receive CMS funding and reimbursement, but these POHs cannot expand (facilities, number of beds, etc), and new POHs can’t be created.

POHs have essentially been frozen in time since 2010. Kind of like Pompeii?

Dash’s Dissection

The ban on POHs has resulted in the following:

- Unrestricted market consolidation of non-POHs.

- The loss of the doctorpreneur.

- The loss of efficient and effective focus factories.

Market Consolidation: Physician-Induced Demand and Cherry Picking

The whole “physician-induced demand” and “cherry-picking” arguments against POHs served as a distraction from non-POHs that engage in physician-induced demand and cherry-pick patients.

Recall, the impetus for the POH ban was incumbent hospitals fearing competition from specialty hospitals that out-compete them in quality, efficiency, and costs. By eliminating the creation and growth of POHs, non-profit and for-profit hospitals built their market power through rapid, seemingly unrestricted consolidation. Stark Laws don’t apply to health systems (remember, “whole hospital exemption”), so hospital-employed physicians could refer patients to their health systems’ vertically integrated imaging centers or specialists (induced demand). The increased market power has also allowed health systems to charge higher prices for services in negotiations with insurers.

Additionally, many academic health systems (non-profit) engage in blatant cherry-picking of patients through segregated care models (although they would never admit to care being segregated). Essentially, healthcare delivery at these institutions is segregated by insurance status, leading to inequitable care as health systems save on expenditures. In some cases, there are two completely different buildings for patients on Medicaid and commercial insurance.

And it should be noted POHs provided a significant community benefit through their taxes and charity care. Non-profit hospitals, on the other hand, are exempt from taxes, but many fail to provide their required community benefits.

The Loss of the Doctorpreneur

The ban on POHs may also have limited incentives for physicians to become doctorpreneurs.

Physicians have a unique combination of skills and knowledge in healthcare services, science, and medicine, and are ideally positioned to identify inefficiencies in care processes and innovate. One of the primary incentives for innovation is the potential for financial rewards, which is why POHs were a breeding ground for physician innovation. In the absence of profit incentives, especially in the context of physician burnout, the doctorpreneur is a rare breed.

Moreover, the absence of POHs may have discouraged physicians from pursuing entrepreneurial ventures, and as a result, may have hindered the development of innovative models of care delivery that could have improved patient outcomes and lowered costs. Why pursue an entrepreneurial endeavor if your hospital is going to own it all because of its IP rules?

The Loss of Focus Factories

Lastly, I must bring in my healthcare systems engineering background to emphasize the utility of “focus factories,” which define specialty hospitals.

- “Focus factories” in healthcare refer to specialized centers that focus on providing high-quality, efficient, and cost-effective care for a specific medical condition or procedure.

By focusing on a narrow range of medical conditions or procedures, these centers can improve efficiency, reduce waste, and minimize errors.

Shouldice Hernia Hospital, for example, is a specialized hospital in Canada that focuses solely on the diagnosis and treatment of hernias. Shouldice is recognized worldwide for its high success rates and low recurrence rates, which are attributed to its specialized focus and standardized, patient-centered approach to care.

By optimizing its processes, Shouldice can achieve high levels of efficiency and cost-effectiveness. For example, the hospital has a standardized patient pathway that helps to streamline the patient experience, reduce waiting times, and minimize the risk of complications.

So, knowing the history of POHs and the benefits they provide, should we bring back POHs?

Incorporating risk-based payments into POHs’ reimbursement would make them even more effective by achieving three objectives:

- Preventing “cherry-picking” by incentivizing hospitals to treat sicker patients who are typically reimbursed at a higher rate.

- Reducing over-utilization of services by paying POHs a capitated rate for each patient, which encourages appropriate care rather than maximizing service utilization.

- Driving efficiency and improving the bottom line by incentivizing POHs to streamline their care processes and save costs while improving patient outcomes.

It is unlikely that AHA and FAH could use their “cherry-picking” and “physician-induced demand” arguments against POHs if risk-based payments were incorporated into their reimbursement. The risk-based payment model would align with the goals of value-based care, which emphasizes quality over quantity of care, and would incentivize POHs to provide quality care to all patients regardless of their health status or insurance coverage.

In summary, the Affordable Care Act effectively banned physician-owned hospitals. The effective ban followed lobbying efforts from non-POH organizations such as the American Hospital Association and Federation of American Hospitals. Non-POHs feared increased competition from POHs that were providing higher-quality and more cost-effective services, attracting patients and insurers. Since the ACA’s enactment, POHs have been frozen in time. It’s time for a thaw.

OUTSIDE THE HUDDLE

1) The Impact of Vertical Integration on Physician Behavior and Healthcare Delivery

Researchers found that gastroenterologists significantly changed care delivery processes after vertical integration. This adds to the piling evidence that while integration may improve operational efficiency, it negatively affects quality and overall spending. I wrote about the “Golden Age of Older Rectums” last year, discussing how private equity-backed firms are buying out gastroenterology practices left and right. There are no signs of slowing down.

2) Estimated Tax Exemption for Nonprofit Hospitals Totaled $28 Billion

KFF estimated the value of tax exemption for nonprofit hospitals was nearly $28 billion in 2020. For nonprofit hospitals to qualify as “tax-exempt,” they need to provide sufficient benefit to their communities. Recently, these hospitals have faced increasing scrutiny for failing to provide such community benefits. In fact, they have been found to take aggressive steps to collect unpaid medical bills, including suing patients. Fellow Huddler Sunjay Letchuman wrote about it here.

3) Microsoft Integrates GPT-4 into Nuance’s Dragon Products

Microsoft integrated GPT-4 into DAX Express, removing human checking previously required to return results to physicians in seconds. DAX listens to doctor-patient conversations to transcribe notes. Before, the notes were reviewed by another human to ensure accuracy, which took several hours. With DAX Express, the human is removed. While this technology is still nascent, there’s great potential for it to transform clinical workflows. I wrote about the potential here.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, share it with colleagues. Sign up for the Healthcare Huddle newsletter here.