27 September 2022 | Climate Tech

Will you eat the bugs?

By

The insects are coming. En masse.

Sound like your worst nightmare? Don’t worry, that’s not quite what we mean. Unless you’re a meat-based pet food company. In which case, yes, bugs are on their way to eat your lunch.

Much has been made of late about whether humans should eat bugs to cut down on other products, like red meat, that are taxing on the environment. So much so that a cottage industry of conspiracy theories has sprung up around whether the World Economic Forum wants to reduce Westerners’ standard of living drastically. “Will you eat the bugs?” has become a meme.

Newsflash, 2 billion people worldwide already do.

Nor is whether humans themselves should be salivating for insects the right messaging. Using insects in animal feed and pet food industries alone could drive climate impact. That’s before anyone even ever tries to serve you a bug burger.

The market for insect farming is growing rapidly, too. By 2030, analysts estimate insect protein demand for livestock feed will balloon from 10,000 metric tonnes to 500,000 metric tonnes, a 50x increase in less than a decade. And companies are raising big rounds with those tailwinds in their sails. For instance, InnovaFeed raised a $250M Series D to enter the U.S. with its vertical insect farms, where insects process agricultural waste.

That’s where insect farming and cultivation come in. Not only can insects provide a feedstock for agriculture or serve as a source of protein for pets. They can also process and convert food waste in the process of turning into animal feed or protein alternatives.

That’s what’s on the menu today.

When it comes to insect cultivation, companies across the world are scaling production of a few types of bugs in the mealworm and black soldier fly families specifically. These voracious mini-machines devour all types of organic waste, efficiently converting garbage into protein and fat in their bodies. Once mature, the larvae enter a pupae stage, where they eventually grow into flies and beetles.

When scaled, this protein and fat can serve many functions in the feed industry for pig, poultry, and fish markets, which are also less regulated than trying to sell to humans. People are much more lax with what chickens eat vs. what they themselves eat, even if they end up eating said chicken. And finding protein-rich feed that is consistent and available year round isn’t easy for farmers; insect feed is emerging as a promising new market that can be produced in both decentralized and centralized arrangements.

Ynsect in France, which has raised north of $400 million in funding, takes a centralized production approach by constructing vertical insect farms, each of which is capable of producing 200 million pounds of mealworm products per year and employs 500 people. To those who are squeamish around worms, it’s probably a good idea to stay far, far away from these factories.

While Ynsect’s long-term goal is to sell insect protein and oils for human nutrition using mealworms with proprietary genetics, they entered the feed and fertilizer market to start. Their poop, otherwise known as frass, can function as a nutrient-rich fertilizer amendment that’s sold to farmers.

Down in Australia, we see a more decentralized bug production beginning to take off. A farmer-turned-deep-tech entrepreneur, Olympia Yarger of Goterra, engineers mealworm and black soldier fly micro-factories that fit neatly in shipping containers and can collocate with sources of food waste. Each unit can process up to 5 tons of organic biomass per day. Operating across Australia, Goterra is scaling its modular units worldwide to expand market share, and they’re preparing for a fundraising round to fuel this expansion.

Nor do insects have to end up as feedstock for agriculture to avoid onerous regulations. Take Jiminy’s, an insect-based dog food company in the U.S. That’s another ‘animal’ industry that offers a smoother entry point to revenue. Catering to higher-end pet owners doesn’t mean skimping on climate impact, either. Pets are massive meat eaters in aggregate.

Unlike the plethora of synbio food and materials companies that have stolen the hearts of many a VC enamored by their enormous potential (but unproven scalability), insect farming already scales and can do so with strong unit economics. Another argument for not reinventing nature is the plant-based meat category, which has come on hard times of late and may turn into a category failure altogether. No need to recreate the biological wheel. Instead, by harnessing the naturally existing biology of insects, the scaleup risk is less technological and more centered on financing, the market, and the supply chain (e.g., access to cheap, consistent, uncontaminated organic waste).

Insects driving impact

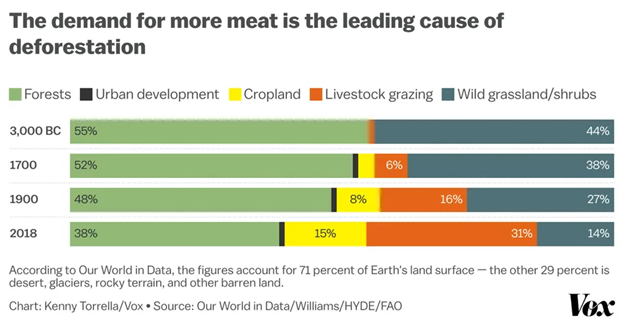

You’ve all heard about the environmental impact of meat. Cows burp methane emissions. Rearing pigs and cows is an energy-intensive enterprise. And raising them also requires a lot of water and land use. Forests are often clear-cut to make room for ag; cattle ranching is a major contributor to deforestation in the Amazon, for instance.

If insects can displace even a small fraction of the protein needed to feed cattle, pigs, and chicken meat and dairy, that’s a clear path to positive climate impact.

Replacing meat used in pet food is an excellent opportunity on that front. It doesn’t require convincing anyone to eat insects themselves. Your dog is probably more than happy to dig up and eat worms in the backyard, anyways. If pets in the U.S. revolted and declared independence, they’d constitute the 5th largest country in terms of meat consumption.

Plus, displacing meat isn’t the only issue re: the environmental impact of food and agriculture.

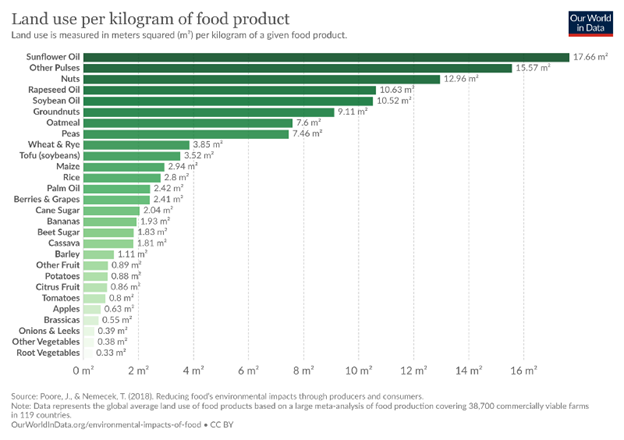

Many of the most ‘staple’ crops worldwide also have their fair share of challenges. Take soybeans and sunflowers, for instance. They rank low in efficiency — i.e., it takes a lot of land to grow soybeans and sunflowers to produce even small amounts of the primary end products they’re used for, seed oils. Higher land use often equates to more deforestation.

Further, synthetic nitrogen fertilizers used to boost crop yields of almost all plant crops are bad for the environment, too. While critical to supporting global population growth, fertilizers produce nitrous oxide emissions, which have 300x the global warming potential of CO2 over short time spans. And plants don’t soak up all the nitrogen fertilizers bathe them in — when water runs off farms, it carries excess nitrogen, polluting waterways and contributing to algal blooms.

Challenges beyond meat in food and agriculture don’t stop there. Another major source of global warming potential comes from agricultural waste that rots on farms or in landfills. Farm and food waste can create more methane emissions absent proper processing techniques.

Cultivating insects can help on all three fronts.

For one, livestock is fed a combination of staple crops alongside other inputs like crop residues. Cultivating insects to feed the future livestock can cut down on land use requirements and ease the impact of expanding agriculture for staple crops, even if only to a small degree.

Secondly, frass, the waste from insects, can be used as a fertilizer when produced in large volumes, like from an industrial insect farm. It is worth noting that frass isn’t as highly potent as synthetic nitrogen fertilizers have come to be, but even displacing some traditional fertilizer use can have a big impact.

Finally, to restate what has been a focal point in this piece so far, insects have miraculous waste conversion capabilities. They’re not just protein. They’re waste-to-protein transformers that can process organic matter that otherwise rots on farms and landfills and produces emissions. And increasingly, people are looking to cultivate insects with even more astounding waste conversion properties, like plastic-to-protein.

What about humans?

Will you eat the bugs? This question, which has become a calling card for

conspiracy theorists and anti-climate crusaders on Twitter, does still embody a challenge for the burgeoning bug industry, even if it’s not the foremost concern for companies like Goterra or Ynsect. Are people willing to eat them? Or even feed them to Fido?

For one, it’s important to note that humans have eaten bugs forever. As we said earlier, approximately 2 billion people worldwide (~25% of the world population) regularly eat bugs. Suggestions that eating them is anathema to civilized society are misguided and veiled racism at worst. The E.U. also recently deemed bugs perfectly fit for human consumption, and their regulations on human food are much more stringent than laws in the U.S.

Still, if a share of the global population turns up their nose at the notion of eating bugs, that’s noteworthy, as it will limit the total addressable market. Another valid criticism could come from folks who are vegetarian or vegan. For their purposes, especially if their focus is ethical, cultivating and eating bugs doesn’t solve much and is less ‘competitive’ than other alt proteins.

The net-net

We’re bullish on bugs. Have we started eating them? Not yet. But presented with solid options, I can confidently say I’d happily try them.

And whether we eat them or not isn’t the main concern right now. The climate and business opportunities in insect cultivation are ample. And it doesn’t require folks like us to stop eating meat. Replacing other inputs in agriculture and replacing meat in the pet food industry is low-hanging fruit. Whether you’re an investor, operator, or just climate-curious, don’t ignore insects.