02 August 2022 | Climate Tech

Important transmission

By

Tl;dr

Some of the biggest news in energy this year was overshadowed by the IRA, a bill in Congress that would flow $369B to climate and energy solutions.

$369B is big. But so is the newly approved grid expansion plan out of MISO. Here are the deets:

- Who: Midcontinent Independent System Operator (“MISO”), an independent organization managing electricity in 15 states & Manitoba.

- What: Last week, MISO approved the largest-ever build-out of electricity transmission in the U.S., to the tune of ~$10B for 18 new high voltage transmission lines.

- Where: Crisscrossing the northern Midwest, including Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and slivers of other states.

- How: A massive amount of work goes into planning, approving, and later, executing this type of work. Aligning stakeholders for this scale of infrastructure is incredibly hard and often fraught.

- Why: Across the U.S., grid infrastructure is aging, coal-fired power plants are shutting down, and new renewable energy projects are coming online. More transmission is needed to connect renewables to end users.

Begin transmission

While there was plenty of tough news in climate as usual last week, there was much hooting and hollering as $369B for climate and energy from Congress came practically out of the blue.

Any other week, another energy headline would have dominated the ‘good news’ category. Instead, it ended up taking a backseat. Which is unfortunate, because organizations like MISO aren’t exactly discussed at length in most climate circles to begin with. MISO is the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, a not-for-profit, independent organization coordinating electricity in 15 U.S. states. You can think of MISO in a comparable category as ERCOT in Texas if that happens to be more familiar.

When people suggest, in general, that the U.S. should invest in more renewable energy projects, they’re proposing a whole host of things. It’s one thing to break ground on a renewable energy project, presumably siting solar or wind turbines in a good area that gets a lot of sun or where the wind blows consistently.

How you connect to the grid and get that electricity to paying customers is a whole ‘nother question. Transmission is a critical component of the consideration set. There’s no shortage of new renewable energy projects in the U.S.; in fact, there’s already more than the grid can maximize.

In speaking with the CEO of another energy-focused company last week, he noted that typical wind projects in the U.S. curtail their potential electricity production by 30-40% by year five post-completion. Part of the reason for that is competition from other renewable energy projects – like McDonald’s and Burger King, renewable energy projects often converge on similar locations given they site based on the same criteria. Another reason for curtailment is the lack of sufficient transmission. If you think of transmission like a hose, and imagine trying to run water through it (electricity in this case), the thinner the hose, the slower you’ll be able to move water. Beyond a certain point, you can’t move any more water more quickly. That’d be too much pressure.

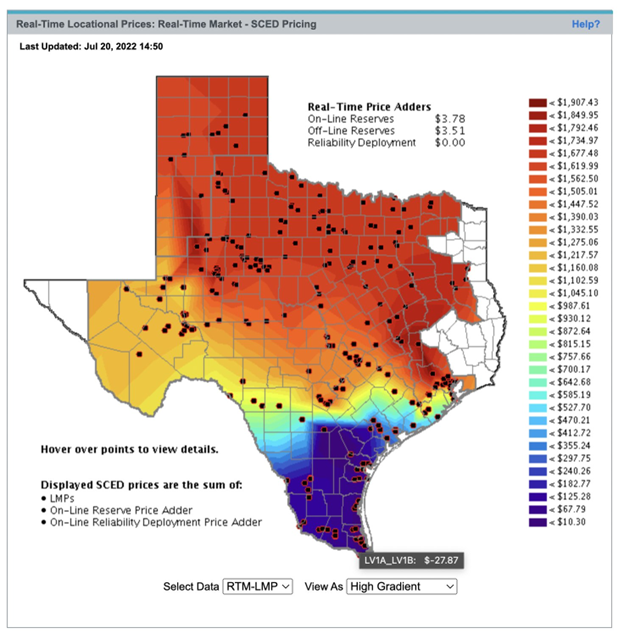

To illustrate another example of what happens when transmission isn’t abundant, let alone built at all, let’s look at what happens in ERCOT (Electric Reliability Council of Texas) reasonably often. High heat + faltering power generation in some areas of Texas recently strained the grid as consumers cranked their A/C. At the same time, there were considerable disparities in prices between regions separated by less than 100 miles:

Theoretically, you could transmit some or all of that cheap power along the Gulf in southern Texas to other parts of the state where electricity prices were high. That would require, you guessed it, significant investments in infrastructure and transmission.

MISO makes history

Significant investments in transmission are exactly what MISO greenlit last week. Their newly approved plan will include the largest-ever build-out of electricity transmission lines in U.S. history.

The plan includes 18 new transmission lines and aims to unlock 53 GWs of new renewable energy projects across the region.

While this is a significant milestone, it’s ideally the tip of the spear as far as additional, similar projects across the country are concerned. To fully decarbonize electricity while producing more to meet higher demands that technologies like EVs will demand, new transmission lines and more energy storage will have to crop up everywhere in the coming decades.

Sure, this requires an upfront investment. But over the long haul, with plummeting costs for wind and solar, the math should be borne out and yield consumer savings ($37B over 20 years, by some estimates). More transmission should also yield more resilience. If you can source power from a patchwork of different plants, that higher optionality equals more redundancy (as illustrated by our ERCOT example above).

Aligning stakeholders to plan for new transmission is notoriously difficult. Not inherently because of its technical sophistication. As Robinson Meyer wrote in the Atlantic a year ago:

Since 2009, China has built more than 18,000 miles of ultrahigh-voltage transmission lines. The U.S. has built zero.

The main problem in the U.S. is stakeholder alignment. I.e., a combination of NIMBYism, complex regulations that vary across districts and states, environmentalists and conservationists (i.e., concerned with habit disruption), and utilities, whose interest isn’t always in seeing electricity prices fall for consumers. Superpower is the go-to book to read about one man’s efforts to build high voltage transmission in the U.S. if you’re interested.

A month ago, the Biden admin and the DOE earmarked $2.5B for new large-scale transmission lines and to upgrade existing lines. The MISO plan is a bigger deal, though, and was likely years in the making. Even still, it faces criticism. One nuance is that many states within MISO’s purview have right of first refusal laws that grant utilities the exclusive right to build new transmission projects. Independent energy contractors say that’s uncompetitive and will yield higher prices for taxpayers.

End transmissions

Next up? The transmission lines need to be built. They are expected to come online in 2028; let’s hope they do, on schedule and within budget.

I’ve already extolled the virtue of the new transmission lines in this newsletter. Without them and many other similar future projects, expanding renewable energy capacity in the U.S. won’t be as beneficial.

The main takeaway for me is a reminder that it’s often the ‘unsexy’ work, i.e., literally laying the groundwork for the nation’s grid, that gets forgotten in moments where technology is making leaps and bounds. Whether you believe fission, fusion, deep geothermal, or some other experimental tech is the baseload power source of the future, you’ll also want to budget significant transmission and infrastructure upgrades into your plans.

The same is true for VC versus other sources of financing – none of the dollars for these transmission lines will come from venture capitalists. Nor is it likely to in the future. While the government is stepping up in many areas of climate tech and energy spending with the Inflation Reduction Act, the dollars earmarked for transmission are pretty modest.

Hopefully, MISO’s action acts as a replicable example for other grid operators nationally.

While this is a significant milestone, it’s ideally the tip of the spear as far as additional, similar projects across the country are concerned. To fully decarbonize electricity while producing more to meet higher demands that technologies like EVs will demand, new transmission lines and more energy storage will have to crop up everywhere in the coming decades.

Sure, this requires an upfront investment. But over the long haul, with plummeting costs for wind and solar, the math should be borne out and yield consumer savings ($37B over 20 years, by some estimates). More transmission should also yield more resilience. If you can source power from a patchwork of different plants, that higher optionality equals more redundancy (as illustrated by our ERCOT example above).

Aligning stakeholders to plan for new transmission is notoriously difficult. Not inherently because of its technical sophistication. As Robinson Meyer wrote in the Atlantic a year ago:

“Since 2009, China has built more than 18,000 miles of ultrahigh-voltage transmission lines. The U.S. has built zero.”

The main problem in the U.S. is stakeholder alignment. I.e., a combination of NIMBYism, complex regulations that vary across districts and states, environmentalists and conservationists (i.e., concerned with habit disruption), and utilities, whose interest isn’t always in seeing electricity prices fall for consumers. Superpower is the go-to book to read about one man’s efforts to build high voltage transmission in the U.S. if you’re interested.

A month ago, the Biden admin and the DOE earmarked $2.5B for new large-scale transmission lines and to upgrade existing lines. The MISO plan is a bigger deal, though, and was likely years in the making. Even still, it faces criticism. One nuance is that many states within MISO’s purview have right of first refusal laws that grant utilities the exclusive right to build new transmission projects. Independent energy contractors say that’s uncompetitive and will yield higher prices for taxpayers.

The net-net

Next up? The transmission lines need to be built. They are expected to come online in 2028; let’s hope they do, on schedule and within budget.

I’ve already extolled the virtue of the new transmission lines in this newsletter. Without them and many other similar future projects, expanding renewable energy capacity in the U.S. won’t be as beneficial.

The main takeaway for me is a reminder that it’s often the ‘unsexy’ work, i.e., literally laying the groundwork for the nation’s grid, that gets forgotten in moments where technology is making leaps and bounds. Whether you believe fission, fusion, deep geothermal, or some other experimental tech is the baseload power source of the future, you’ll also want to budget significant transmission and infrastructure upgrades into your plans.

The same is true for VC versus other sources of financing – none of the dollars for these transmission lines will come from venture capitalists. Nor is it likely to in the future. While the government is stepping up in many areas of climate tech and energy spending with the Inflation Reduction Act, the dollars earmarked for transmission are pretty modest.

Hopefully, MISO’s action acts as a replicable example for other grid operators nationally. To get where we want to go however, more and different modes of action that can spur more grid & infrastructure investment will be necessary, too.