12 October 2023 | Climate Tech

The false binary in carbon markets

By

Permanence in carbon removal refers to the predicted duration that carbon that has been removed will stay out of the atmosphere.

Permanence matters. If carbon is removed and then released back into the atmosphere one year later, not that much has been accomplished. And carbon removal solutions, of which there are many, all offer different degrees of permanence.

There’s a growing divide in carbon removal between parties who focus more on permanence and parties who care more about scale and cost. Often, there’s at least some level of a tradeoff between the two. For instance, planting trees can certainly remove carbon and be done relatively cheaply. But those trees aren’t necessarily a highly ‘permanent’ store of carbon.

As an example of the divide, two tech giants – both of whom, to their credit, fund a wide range of climate solutions – argued about permanence at an event during Climate Tech Week in NYC. Bill Gates supports solutions like direct air capture because they’re more ‘proven,’ by which I interpret him to mean it’s easier to confirm how much carbon a machine ingests and that the subsequent underground storage of said carbon is more permanent. On the other hand, you have folks like Marc Benioff, who wants to plant a trillion trees.

Beyond these two titans of industry, broad coalitions of corporations, solution providers, policymakers, and other stakeholders are increasingly split on this issue. Should they be?

The siren song of ‘permanence’

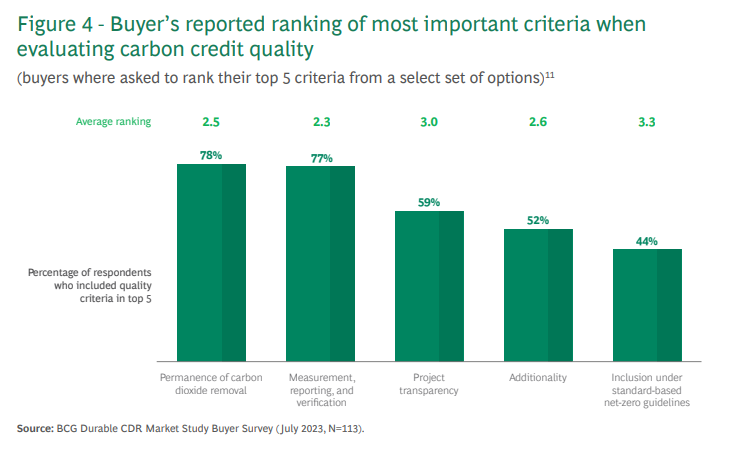

Increasingly, major buyers of carbon removal credits and investors in the industry side with Bill. Permanence is the most important criterion for many of them in evaluating their carbon removal purchases (as visualized below, per a recent BCG report).

I don’t blame them. If major corporations decide to invest in carbon removal, that’s laudable. They get to decide what they buy and what they care about. And they understandably want to avoid the PR fallout that has become so common with nature-based projects that claimed emissions reductions results which, under future and further scrutiny, weren’t up to snuff.

I’ve written glowingly about the growth of the carbon removal market, especially about solutions tailored to deliver permanent sequestration. I stand by that.

There are dozens of Guardian articles and other studies highlighting carbon avoidance or avoided deforestation projects that eventually failed in some capacity, whether because forests were logged, burned down, or because project developers overstated the value of the project in CO2 terms in the first place.

Those are real problems. All projects that monetize some form of carbon-related service should be held to high standards, as should the companies that tout their investments in said solutions.

Hence, permanence is a perfectly understandable priority for many actors in this space. That’s not a bad thing. I feel the siren song of permanence myself, deep in my bones.

But what’s lost if permanence ‘wins’ and we propagate a binary that pits less permanent carbon removal solutions against things like direct air capture?

Beware the binary

As we’ve established, there’s a growing divide between the proponents of more and less ‘permanent’ solutions for carbon removal. Next question: Should that binary exist at all?

The danger of a false binary is that once you establish sensible, good-faith arguments in support of one ‘camp,’ it threatens to discredit the value of the other camp. Were there carbon market actors who, in the 90s and early aughts, just wanted to make money, score PR points, and take advantage of insufficient measurement and oversight in a nascent market? Totally.

But should we abandon nature-based solutions as a result? Of course not. If we all align behind permanence, who will speak for (and finance) the trees?

Maybe forestry-linked projects aren’t perfectly suited for the carbon market, especially as it matures. But that isn’t cause to abandon nature-based solutions and ecosystem restoration projects. We can’t let these climate solutions ‘fail’ because the incentive structure we built for them did. That’s on us, not the trees.

As noted by Peter Olivier, Head of New Markets at UNDO, in a recent conversation of ours:

If the carbon market had proven permanence wasn’t an issue over the last 30 years, then we wouldn’t be seeing this ‘flight to quality’ narrative take hold now. Much of the myopia we see in the market with respect to permanence in carbon removal is a direct result of the lack of permanence of projects issued over the last 20 years. It’s especially unfortunate because so much high-quality nature-based work that could be done today is tarred with the same feather.

Abandoning nature-based solutions would be the very definition of the proverbial ‘missing the forest for the trees.’ Forests are about much, much more than carbon.

Nature-based solutions offer innumerable benefits beyond carbon. They don’t have to slot into the permanence debate or into carbon markets at all, per se.

- Scale: Nature-based solutions are often more readily and cheaply scaled. Whether you connect emotionally with soils or mangroves on shorelines or forests or grasslands or some other ecosystem, they all offer significant (often overlooked) carbon removal and sequestration benefits. Are these ‘permanent’ stores of carbon? No. But does mitigating emissions, even for ten years, have value? Yes.

- Co-benefits: The co-benefits of ecosystem restoration are too many to list. Ecosystem restoration work benefits biodiversity, a beat I spent a lot of time this year covering. Ecosystem services are also good for environmental remediation and for fighting other forms of pollution, beyond greenhouse gasses. They’re good for local communities. Heck, they can offer adaptive benefits that help us deal with climate change’s effects.

- Other economic value: If existing markets are your thing, much of global GDP is inextricably linked to natural resources, whether timber, agriculture, or other. Preserving ecosystems is critical to the continued functioning of the global economy, without ever even introducing the topic of how to decarbonize society, carbon, or biodiversity.

And, lest it go unsaid, there are many climate-tech startups, like Mast Reforestation, that take a rigorous, good-faith, and thoughtful approach to monetizing forest regeneration via carbon credits. I support them and hope they succeed, even if all they ever ‘sell’ is focused on carbon.

The net-net

If you ask me to pick a side between permanent carbon removal solutions and ‘less permanent’ ones, I respectfully decline to engage. I don’t consent to the binary to begin with.

In a podcast episode I released today with Chris Tolles, the CEO of YardStick PBC, a company commercializing soil carbon measurement technologies, we hit on a similar point. Here’s Chris:

I try to explore a world in which [arguing about all these questions] is a false binary. Zero-sum thinking is false. Of course, there are trade-offs. I run a company where I appreciate limited resources. Nonetheless, I think it’s incredibly important to press into that tension [in the binaries we’re presented with] because that’s the real stuff right there. When we manage for single variables, we mess everything up.

The problem with binaries is the reductive thinking they force us into. They pigeonhole us, for the umpteenth time, into evaluating everything in terms of single variables, be it carbon, or price, or permanence.

Then, as they become entrenched and people, policies, companies, and the flow of capital alike concretize around them, it starves other vital conversations, perhaps the most important ones, of oxygen. Binaries force us into a scarcity mindset, thereby blinding us to the broader range of possibilities (and, in our case, possible climate solutions).

From my vantage point, the critical question, and the one that’s currently under-discussed, isn’t how to make nature-based solutions fit into the carbon market as it grows and matures. Instead, let’s ask, from a first principles basis, what are the right systems, solutions, and services to scale ecosystem restoration and nature-based solutions?