23 July 2023 | Climate Tech

Charging batteries with batteries

By

We spend a lot of time discussing the benefits of clean energy technologies in this newsletter, especially those geared at decarbonizing the power sector.

As far as the full decarbonization picture is concerned however, that’s just one piece of the pie. Decarbonizing transportation (and other industries, like agriculture) are whole other beasts entirely.

While energy consumption is a metric with its own drawbacks, the chart below does a good job visualizing how much fossil-fuel dependency lies outside the power sector:

Here’s some good news though as it pertains to decarbonizing these other sectors. EV sales are skyrocketing, which portends good things for transportation decarbonization.

Still, reshaping society so most cars are electric will require tectonic shifts outside of the engines.

Boondoggled: A litany of EV fast charging challenges

Charging is an obvious area that will require significant change. As we’ve explored in other content, for EVs to really take off, charging needs to be as ubiquitous, accessible, and seamless as going to a gas station is.

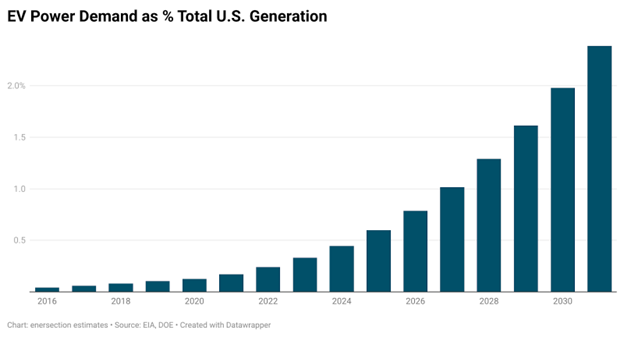

Similarly, for EVs to be as good for the environment as possible, it’s also crucial that there are sufficient clean electrons to charge EVs. As EV market penetration increases, it’s estimated that ~2% of all electricity in the U.S. will be used to charge EVs by 2030. That’s a meaningful bump in electricity demand, not to mention demand for low-carbon electricity.

So far we’ve identified that we’re going to need a lot more charging infrastructure across the U.S. and will need to generate more clean power to meet EV charging demand. That in and of itself is a challenging proposition.

But there are more challenges to introduce here. For one, even existing charging infrastructure installed in recent years is already flagging. Depending on provider and geography, a quarter or a third of public chargers may be broken at any point in time.

Further, building new charging stations isn’t as easy as choosing a location and putting steel in the ground. The grid itself – one of a few of the most critical backbones of our society – isn’t always equipped to deal with the additional strain that new charging stations, especially fast-charging stations, would put on it. When you turn on high-powered chargers, you’re drawing on the grid immediately. Some cars require a 350 kWh charger, equivalent to charging a big commercial building [albeit for a short amount of time].

In fact, fast charging can be so energy-intensive that a 2019 BCG study estimated that utilities will need to invest an additional $1,700 to $5,800 per EV in infrastructure upgrades in coming decades. Given it’s already been four years and we’re further out on the EV adoption curve, I wouldn’t be surprised if revised BCG estimates came in at the higher end of that range. Up to $5,800 per car!

To summarize, we have a few key challenges on the EV charging front:

- Availability

- Reliability

- Infrastructure upgrades

Filling the fast charging gap

Electric Era is working to solve all of the above-listed challenges for EV charging. And the company sits at the intersection of leveraging energy storage and building infrastructure. Specifically, Electric Era uses battery energy storage as a wedge to make deploying EV charging stations easier and make the entire EV charging operation more efficient.

When I sat down with Quincy Lee, Electric Era’s CEO, for a conversation recently, he commented on how EV fast charging is “totally boondoggled.” And in his mind, charging difficulty and availability are key issues that, alongside things like range anxiety, are keeping more customers from buying EVs.

To counteract these trends, Quincy founded Electric Era to make EV fast charging “ubiquitous, affordable, and reliable.”

When they set out to build a tech solution to solve EV fast charging’s challenges four years ago, Quincy and team identified grid-level challenges as the first layer of challenges innovation they would need to solve. While the grid is a constraint on EV charging, Quincy is also the grid’s biggest fan. Again, in his words:

Arguably, the grid is one of the most impactful pieces of technology humanity has ever created.

When you hold the grid in this high esteem, you also think a lot about how to safeguard it. And as you think critically about adding more EV charging to the grid, you realize, like Quincy and team did, that there’s a mismatch between the high power that fast charging demands and the relatively low power limits that most of the distribution level grid in cities across America have.

While upgrading and rebuilding the entire distribution grid is probably something that needs to happen over coming decades to better enable the energy transition, that isn’t going to happen as fast as charging needs to be deployed.

All of this informed Electric Era’s approach to building its solution. They had to create tech that reduced grid strain introduced by new charging stations.

That perspective led them to add a battery to their ‘PowerNode’ stations. The battery sits between the grid and the charger; by incorporating this intermediate energy storage component, Electric Era’s stations can divorce the charger’s ability to draw power quickly from the grid.

The battery can be charged by the grid more slowly and during times of day when clean power is readily available (e.g., the middle of the day when there’s a lot of sun) and discharged quickly at a later date when drivers show up to charge. In the same way batteries in the grid can help mitigate duck curve power demand patterns, batteries paired with EV chargers can do the same:

In sum, PowerNode’s battery reduces strain on the grid and allows discharging above grid limits. Quincy described the hardware design of the PowerNode as a “Technology toolkit to shortcut the process required to add EV fast charging.”

Compounding a first mover advantage

Hardware is only the first part of the story here. Software may be an even more critical component of this conversation. Quincy described how software to optimize and harmonize their systems is where the real leverage in their business comes from. Here’s the money quote from our conversation:

We live in a software-effectuated world: I think the most compelling and high total addressable market businesses of the 21st century will be built at the confluence of hardware and software. If you have bits giving life to atoms, then you really can create a lot of shareholder value.

What precisely does software do in Electric Era’s ecosystem? For one, it helps them ingest and analyze a monumental amount of data. Forecasting demand and supply is as important for Electric Era as it is for a company operating a grid-connected battery. They need to know when their systems will be tapped for discharging (by EV owners looking to charge) vs. when power on the grid will be cheapest and cleanest (i.e., an ideal time to charge batteries rather than discharge them).

This is no small coordination problem that cuts across the entire hardware stack and the data it produces, as Quincy helpfully laid out:

It’s a big ordeal… we have to provision a highly reliable EV fast charging station, including all the chargers, our onsite edge compute system, all the safety high voltage electronics, an inverter that couples DC to AC power, the batteries [and more]. It also needs a comprehensive supply chain with real-time insights and supply chain management systems. Imagine atoms worldwide assembling in the same time domain at the exact same instance. That’s what you’re trying to manage.

Incidentally, if you’re looking for a ‘real’ AI use case vs. over-hyped ones, these load management applications are a prime example. Operators will get compounding benefits from studying the data at their stations and projects over the years, getting better and better at forecasting demand and optimizing their operations. The extent to which the value of this operational data compounds also lends companies like Electric Era that are getting in on the ground floor of the race to deploy EV charging a sizable first mover advantage.

Better data and forecasting should also help Electric Era on the reliability front, which also begins to bridge us into a discussion of their business model. Electric Era sells its stations to the stakeholders like gas station operators or retailers with space to host them. This isn’t a one-and-done handoff, however. The company both sells the station and provides continued services to customers, part of which is a reliability guarantee.

Specifically, Electric Era guarantees uptime up to 99.5%, which is ludicrously high compared to what’s typical in public charging.

Structuring their business this way creates a long-term incentive alignment surrounding reliability and also puts the onus on them to be able to deliver it. That brings data back to the fore; the more Electric Era can understand why a station’s ability to offer charging ever falters, the more likely they can be to prevent that from happening in the future.

And if they can make good on their reliability goals at scale, they’ll drastically outperform other fast charging station providers and operators.

Speaking of scale, Electric Era’s first live demo took place in Knoxville in 2022. More than halfway through 2023, they have eight customers and 19 total deployments across nine states.

That’s strong growth. But they want to deploy 10,000 PowerNode stations by 2030. Can they 500x their footprint in six or seven years?

I hope so. They’re also competing with most major OEMs to claim future charging market share. Just yesterday, GM, Honda, Stellantis, and a number of other car companies are forming a new joint venture and investing up to $1B to add 30,000 fast chargers across the U.S. (paywall).

Ideally, this is a case of a growing pie and there being plenty to go around. But there is also a question of reaching the most desirable sites for chargers first. Not all locations are created equal.

The net-net

Workarounds like Electric Era’s insight to add batteries to EV fast charging will likely do a lot to accelerate climate tech adoption. But should we need workarounds like that at all? The fact that an EV charging company is being built to reduce grid infrastructure upgrade dependency tells you how disjointed our approach to the energy transition still is at times. Much more harmonization of stakeholders, not just data, is still needed.

That’s ultimately why I appreciate Electric Era’s quasi-ludicrous goal to deploy 10,000 stations by 2030. If all stakeholders viewed electrification and transition like a wartime effort, we likely wouldn’t be as hamstrung by things like permitting reform, which threatens to derail the progress of countless climate technologies, not just EV fast charging.