28 May 2023 | Climate Tech

Cash for carbon

By

The past two weeks have seen a flurry of big deals in the carbon removal:

- Chase announced this week that it will pre-purchase 800,000+ tons of carbon removal (for $200M+) from several carbon removal companies.

- Last week, Frontier, a coalition of companies that makes advanced market commitments in the carbon removal space, pre-purchased 112,000 tons of carbon removal from Charm Industrial for $53M.

- Also last week, Microsoft pre-purchased 2.76M tons (!) of carbon captured by Ørsted from their bioenergy with carbon capture and storage efforts.

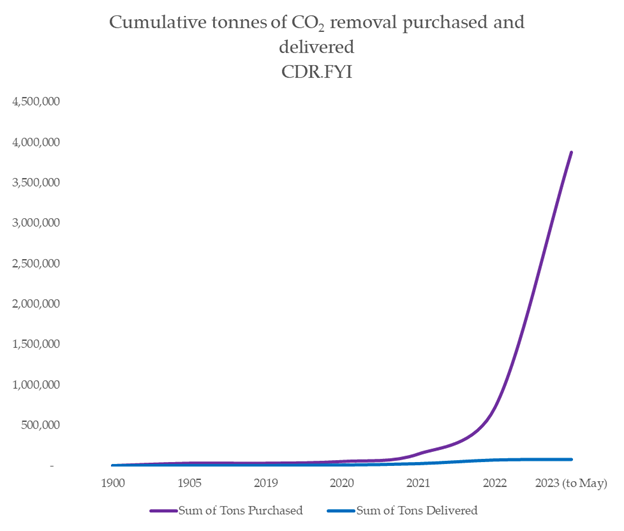

This year the amount of carbon removal ever pre-purchased has ~40x’d.

A mosaic of solutions

The first thing to note is that all these purchases span a wide range of carbon removal and capture solutions. Chase’s combined $200M in purchases allocated capital to direct air capture (Climeworks) as well as to Charm Industrial, which Frontier also supported, for the company’s work in pyrolyzing waste biomass to turn it into bio-oil, which they inject back underground. Microsoft’s big buy is for BECCS, which stands for (bioenergy with carbon capture and storage.

The second thing to note is that the carbon removal volumes pre-purchased here are, in the grand scheme of atmospheric carbon, a drop in the ocean. I say that not to downplay them. The bigger story is the extent to which the money could be catalytic to the industry’s scale-up.

To hone in on one of the above solutions we haven’t discussed much previously, Microsoft’s support of Ørsted may be the most controversial. Ørsted’s BECCS approach involves using carbon capture devices to reduce emissions from biomass burning in thermal power plants.

There are a few big question marks surrounding BECCS.

The first is where biomass used in energy production stems from. If old-growth forests are logged to fuel power plants, and even if the resulting emissions are captured and sequestered, is that a true ‘climate’ solution?

The second is how effectively emissions can be captured. People often point to the fact that no commercial power plants in the U.S. currently use carbon capture systems as evidence that CCS isn’t viable yet. Then again, why would there be? Until last year, there were no commercial incentives to capture carbon, and there’s no regulation on emitting CO2 into the air.

I recently caught up with Adam Goff, SVP of Strategy at 8 Rivers, a climate tech company that commercializes CCS technology (among other tech). He noted that for post-combustion technologies, most capture systems target 90-95% emissions capture rates. That could be better (obviously), but it’s sufficient to shift the calculus on the full lifecycle emissions from a biomass plant (or a natural gas plant, for that matter) drastically.

The third question for BECCS is familiar to most carbon removal or capture projects: how and where will emissions be stored? Ørsted will work with a project called Northern Lights (funded by oil majors) to transport and permanently store CO2 in a reservoir on the seabed of the Norwegian North Sea. Norway has the world’s most advanced offshore CO2 storage capabilities.

With all those questions outlined, it is possible that with sound project design and technical execution, BECCS can be carbon negative. If you burn net new biomass (which soaks up CO2 from the air) and then capture the emissions on the backend and store them safely, you’ve reduced atmospheric carbon (and created energy that likely displaced fossil fuel combustion).

Fun fact, if you look at primary energy, not just power production for electricity, Europe gets more than half of its renewable energy from biomass. So there’s plenty of need for using carbon capture and storage on biomass plants.

Here comes the controversy

There isn’t a climate solution or debate that isn’t mired in controversy. And carbon removal is one of the more controversial. Zooming out, all of this carbon removal activity comes against a backdrop in which international policymakers are questioning whether the world should focus on carbon removal as a climate solution at all.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) has drafted guidance that would deprioritize carbon removal compared to other, more scalable carbon reduction solutions (nature-based solutions), including statements such as:

…engineered carbon removal activities… do not contribute to sustainable development…

Obviously, carbon removal companies object to this stance and made their displeasure known this week. Where should the rest of us land on this?

Within my bubble, carbon removal is often extolled as an exciting set of technologies that are a) moonshots but also b) indispensable. From that vantage point, they are now (finally) getting some of the support they deserve.

But many other people see it differently. ‘Old-guard’ environmentalists rightly call out Chase as one of the biggest funders of oil and gas infrastructure. They see the company’s $200M investment in carbon removal as, at best, a nothing-burger for the climate and, at worst, an intentional distraction or deflection. They comment on my tweets, telling me I’m an idiot for getting excited about this stuff.

It’s also important to remember that all these purchases are for future deliveries of carbon removal. All the companies getting money still have to, you know, scale their 10-100x to satisfy the signed agreements.

There’s big operating, ‘manufacturing,’ and reputational risk here. Operating and manufacturing (by which I mean ‘manufacturing’ carbon removal) risk involves the actual delivery of the carbon removal. The reputational risk concerns how quickly current backers may sour on carbon removal if, in 5-10 years, none of the agreements in 2022 and 2023 come to fruition.

Suffice to say, it’s cool to be excited about how far carbon removal has come in three years. Let’s just be measured about how far it has to go in the next thirty.

The net-net

Here’s something I wrote a while back:

2022 was the biggest year for the carbon removal industry by a wide margin. It’s hard to see interest in carbon removal slowing down this year. I expect the market for carbon removal to expand significantly in 2023…

Huzzah, I was right (for once). 2023 is already another massive year for the carbon removal industry. Nothing else could happen this year and it’d be a win.

Mind you, these aren’t insanely prescient statements on my part. The industry is still tiny; growing a small denominator isn’t that groundbreaking.

I also wrote this a while back:

Now that carbon removal is on the map, things may get more challenging as the rubber meets the road. Many firms are navigating the transition from the lab to the field. That transition inevitably comes with challenges across tech, measurement, or even government permits…

That’s the phase we’re still in. There’s just even more money and attention riding on companies’ ability to execute. The stakes are getting (much) higher!

Of course, the stakes are incredibly high as is. They have been and will continue to get even higher. Climate change is here. It’s happening now. It’s getting worse. I feel like I forget to say that sometimes.

So that’s where I’ll leave you today.