15 April 2023 | Healthcare

Private Equity in Healthcare: the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

By workweek

Private equity firms have increasingly been investing in the healthcare sector, seeking to capitalize on the industry’s growth potential and profitability. However, this trend has raised concerns over the potential impact on healthcare access and quality, as well as the ethics of profiting from healthcare services.

The term “private equity” has been thrown around more frequently in physicians’ and other providers’ social circles. But the strategy behind private equity (PE) is seldom understood.

In this article, I’ll describe PE firms’ thesis in healthcare delivery, highlight PE trends, and dive into the good, bad, and ugly of PE.

How Private Equity Works in Healthcare Delivery

PE firms are attracted to three key characteristics of U.S. healthcare:

- Fragmented, highly inefficient care delivery system.

- Third-party payers.

- Growing industry that’s recession-resistant (for the most part).

PE firms leverage their capital and operational strengths to take advantage of these above-mentioned characteristics to maximize return on investment.

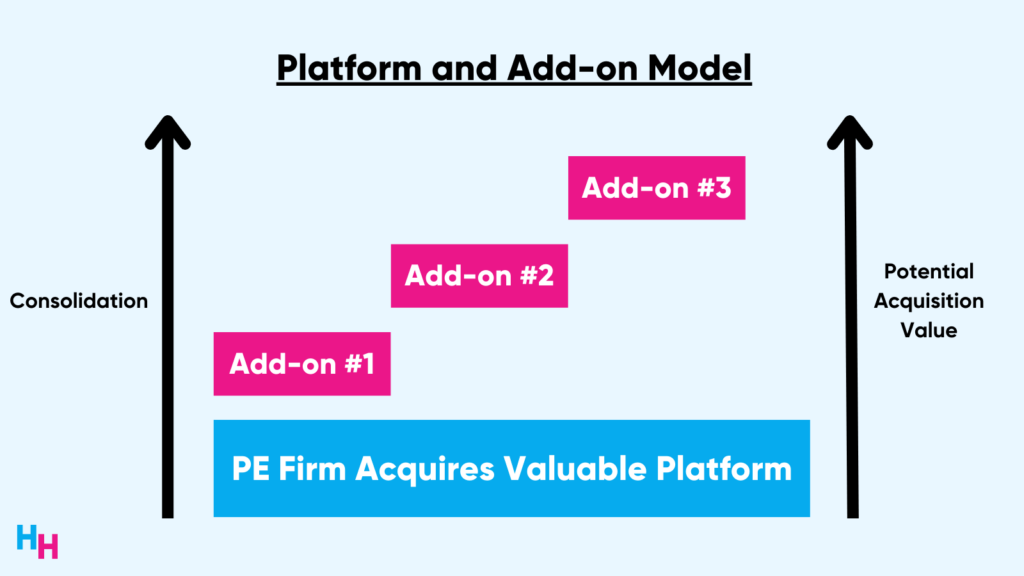

These PE firms typically follow a “platform and add-on” model. In this model, PE firms will first acquire a large and established medical group, cut waste to improve efficiency, and infuse capital to purchase tech that streamlines operations. With the profit reaped, firms will then acquire smaller practices as a way to consolidate. This platform and add-on model allows PE firms to build market power, achieve economies of scale, control referrals, and increase negotiating power with third-party payers.

To acquire a medical group, PE firms use a leveraged buyout (LBO) model. In this model, PE firms raise a large amount of debt to acquire the medical group as opposed to using a large amount of equity (their own money). For example, a PE firm may use 70% debt, consisting of bank loans and “junk bonds,” and 30% equity to purchase an asset.

Who’s responsible for paying off the debt, though?

The acquired entity (the medical group) is responsible for paying off the debt since the PE firm will have used the acquired entity’s assets as collateral. If the medical group can’t pay off its debt, lenders can seize it as collateral (will explain an ugly story later).

So, the acquired entity bears the financial risk of the acquisition—not the PE firm (moral hazard!). Why would a medical group want this? The benefits of the acquisition may outweigh the risks, especially if the medical group has a strong revenue model. With the acquisition, the medical group gets immediate access to capital for new investments, efficiency gains, and tax benefits (because of debt), for example. Note, the physicians and providers of the group typically retain some equity, allowing them to benefit from future transactions.

Overall, these PE firms strive to achieve a 20% annual return on investment while eyeing a three- to seven-year horizon (the time until they sell their acquired assets to another firm or company).

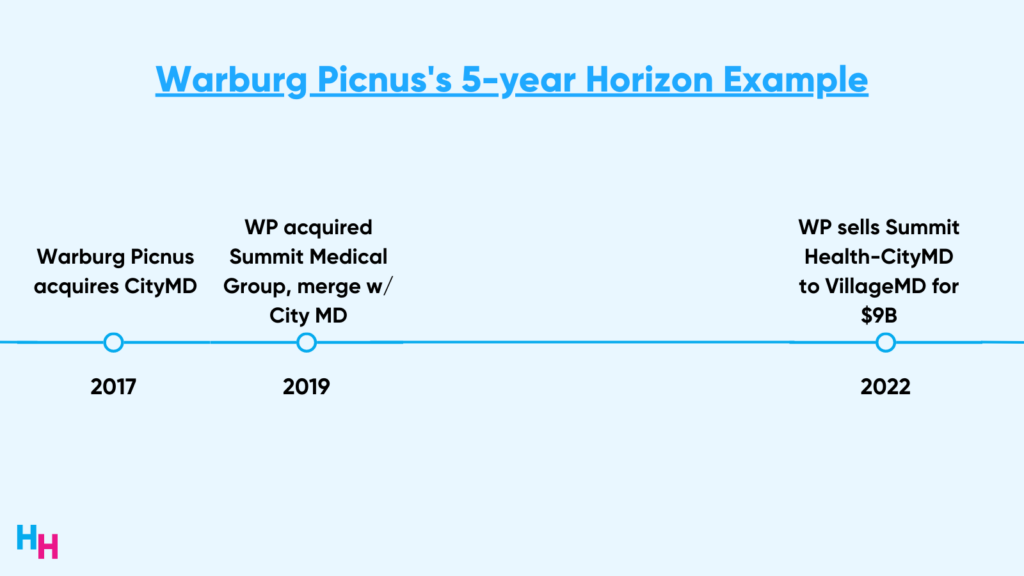

Here’s a real-life example coalescing the above information:

- The Platform: PE firm Warburg Picnus acquired prominent NYC—based urgent care group CityMD in 2017. At the time, CityMD had around 70 locations.

- The Add-ons: Warburg Picnus acquired other local urgent care groups, reaching 100+ locations. The firm then acquired NJ-based Summit Medical Group in 2019 and merged them with CityMD. This increased the value of the two companies tremendously, given how well they complement each other (read more from Blake here).

- The Exit: Warburg Picnus exited Summit Health-CityMD to Walgreen’s VillageMD for around $9 billion at the end of 2022.

#Trending

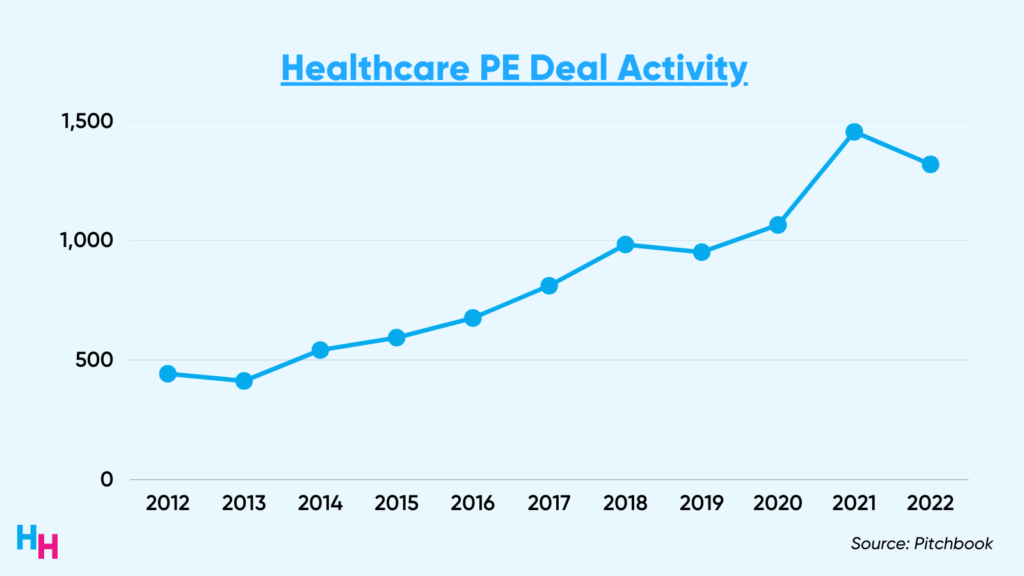

Healthcare services PE deals grew an estimated 200% between 2012 to 2022. “Services” include primary care and multispecialty groups, skilled care and behavioral health, and practice management companies.

It’s safe to say, PE has infiltrated healthcare and shows no signs of slowing down. These firms continue to gobble up physician practices, improving operational efficiency as they eye that three to seven-year horizon. While the return on investment is juicy, does everyone affected by the acquisition (patients, physicians) get to sip the juice?

Dash’s Dissection

The role of private equity firms in healthcare is a subject of much debate, with varying opinions on their impact. While there may be some positives to their involvement, there are also negatives and potentially damaging consequences. As a physician or provider, it’s important to remember that patient care should always be the top priority.

- Any force that benefits patients and providers is good.

- Any force that harms physicians or providers is bad.

- Any force that negatively affects patient care, in any way, is unequivocally ugly.

The Good

Private equity transactions with medical groups provide these groups with immediate capital that they previously didn’t have. This capital can be invested into health tech to improve operations and patient care. Additionally, this capital may incentivize innovation, allowing both the medical group and PE firm to profit off of innovations that better operations and patient care.

And if there’s one thing healthcare delivery needs, it’s innovation.

Firms also may also relieve physicians and providers of management responsibilities, allowing them to focus on delivering high-value care to patients. These firms can improve administrative efficiency and revenue cycles, and aid in implementing quality metrics required by CMS, for example.

Lastly, PE firms may serve as a lifeline for medical groups that struggle to compete with large health systems or locally consolidated medical practices. This strategy would follow the “if you can’t beat them, join them” strategy, allowing these medical groups to remain competitive. Or, PE firms may give an end-of-career physician who built their own practice a comfortable exit.

The Bad

Relinquishment of physician control is inherent in a PE acquisition and, therefore, may lead to loss of physician autonomy. Examples include forcing physicians to increase the number of patients seen per day, perform unnecessary but profitable procedures, or refer patients to other specialist groups owned by the PE firm, no matter the quality of care the specialist provides. In fact, one study of ~600 PE-acquired physician practices between 2016 and 2020 found volume increased by 16% post-acquisition.

Additionally, the “economies of scale” touted by PE firms to support their acquisition sprees have yet to be proven in studies. So, the efficiency gains firms promise to medical groups may be all fluff. In fact, the promise for efficiency gains and improved patient care may just be a front, since the acquisition of more and more practices allows PE firms to leverage more debt financing, leading to a profitable sale of a larger practice (in the range of 8-12x EBIDTA).

Lastly, PE firms consolidating local markets creates an anti-competitive market that affects patients. Economies of scale seem to be a myth in healthcare, in general, as consolidation of medical groups increases prices rather than decreases them. Referring back to the aforementioned study, prices post-acquisition increased by 11% among the ~600 physician practices. And, patients bear the brunt of the costs when healthcare prices increase.

I should note, like all business transactions, non-disclosure agreements are signed by both parties, which limits the availability of data.

The Ugly

The ugliest aspect of private equity is the short-term, highly-focused mission to buy, build, and sell.

The focus on profits seemingly negates the need to ensure patients receive high-value care: care that is high quality and cost-effective. There is evidence showing patients cared for by PE-owned dialysis centers in concentrated markets have higher hospitalizations, lower survival rates, and decreases in staffing compared to non-PE-owned dialysis centers. Additionally, evidence shows gastroenterologists significantly alter care processes, such as in using anesthesia with deep sedation during colonoscopy, after they vertically integrate (with PE firm, for example). Patients’ post-procedure complications increase substantially.

It’s well established that PE-owned hospitals add more profitable service lines and discontinue less profitable ones. These hospitals also have fewer full-time employees, lower patient satisfaction scores, and poorer quality metrics compared to non-PE-owned hospitals.

Hahnemann Hospital in Philadelphia, which served low-income populations, is a poignant example of PE’s focus on profits over patients. It’s also a poignant example of the dangers of LBO, in which the 10-year bankruptcy rate is 18% higher for companies acquired by leveraged buyouts compared to controls:

- PE-backed American Academic Health System acquired Hahnemann Hospital (owned by for-profit Tenet Healthcare Corporation) in 2018.

- To turn a quick profit, AAHS simultaneously sold Hahnemann’s real estate assets to Harrison Street Real Estate Capital—one of the largest real estate investment firms.

- AAHS then quickly filed Hahnemann for bankruptcy in 2019, but strategically excluded Hahnemann’s real estate from the bankruptcy filing.

Vulnerable patients weren’t the only ones affected by Hahnemann’s closing. Physicians who worked at Hahnemann had to find new jobs, residents and fellows had to quickly find new programs, and Drexel University College of Medicine had to find new training sites for their medical students. It was pure chaos:

For-profit providers and safety-net hospitals don’t mix.

Robert I. Field, PhD, JD, Professor, Health Management and Policy, School of Public Health, Drexel University

We physicians and providers must remain privy to PE’s impact on patient care. This includes advocating for greater transparency and accountability from PE firms, as well as government regulation that promotes fair competition and access to high-quality care. While the system allows PE firms to reap profits while failing to improve patient care, we have an ethical obligation to ensure that patients receive the best possible care and that the healthcare industry remains focused on improving health outcomes. Incentives must align.

In summary, private equity’s prevalence in healthcare has increased significantly over the decade. While private equity may provide some good in healthcare, it also may provide some bad and a lot of ugly. Profit over patients is a poor and unethical model in healthcare. More safeguards need to be put in place to ensure patients aren’t harmed by PE.

HuddleChats

Check out my chat with Dr. Adam Brown on Private Equity: the Good, the Bad, the Ugly.

Read the recap here. Watch the recording here.

Outside the Huddle

1) Shifts in the Number of Abortions Post Dobbs Decision

There were around 5,500 fewer legal abortions provided per month in the months following the Dobbs v Jackson’s Women’s Health Organization Supreme Court decision compared to months prior to the decision. The analysis, performed by the Society of Family Medicine, compared legal abortion data between July and December 2022 to April and May 2022 (baseline). An interesting finding, however, is the number of abortions provided via telehealth increased 137% from 3,610 in April 2022 (4% of all abortions) to 8,540 in December 2022 (11% of all abortions). In June, I’ll recap the past year following the Dobbs decision.

2) Top Health Systems Based on Digital Health Portfolio

A new digital health report by FINN Partners and Galen Growth analyzed the number of digital health companies in health systems’ portfolios. The report gives a nice overview of the most innovative hospitals (happy to say Mount Sinai is one of the top 😊).

3) Healthcare Chat Bots and Generative AI

Google plans to test the accuracy and safety of its generative language model Med-Palm 2 with select Google Cloud customers over the next several months. The other big player in the generative AI and healthcare space is Microsoft’s Azure Health Bot. I’ll be covering these players in June, recapping the progress and implications of generative AI. I also plan to host a HuddleChats event (see below). Here was my latest coverage.