01 February 2023 | Climate Tech

U.S. power generation in 2031

By

I recently read Barbara Freese’s Coal – a sweeping history of human’s relationship to coal – and was struck by a passage in which she noted that coal was the #1 fuel source for U.S. power generation. This made sense when I checked when the book was published. In 2003, coal was indeed still the king.

Twenty years later, a lot has changed. Because this is a ‘climate tech’ newsletter, you’d likely expect that I’m about to extoll the virtues of wind and solar power. Not yet, friend.

The biggest shift in the past two decades has been in domestic natural gas production and power generation. Even in the last ten years, the amount of electricity generated by gas has grown more than wind and solar combined. This has helped reduce U.S. dependence on coal and gas has taken the throne as #1 fuel source:

There are several reasons growth in natural gas power generation has outpaced wind and solar. For one, wind and solar were still warming up in 2013, while natural gas capacity boomed in the early aughts following deregulation in several large states.

Secondly, the U.S. is in a globally enviable position; our domestic natural gas production has skyrocketed since 1960 and we produce enough of it to cover all of our consumption. This has kept prices low, making building combined cycle natural gas power plants attractive. The U.S. is such a kingpin in global natural gas production that we drew level with Qatar last year in LNG exports.

On the whole, this has been a boon for climate change mitigation, too. The reduction in coal use over the last few decades has decreased U.S. emissions over that period, even as total energy consumption grew:

Still, converting coal to natural gas alone is neither a sufficient lever to decarbonize, nor is it possible in all places (especially those without domestic production). There’s also an interesting tradeoff between natural gas and renewable energy deployment. Had natural gas not been so cheap for decades, the U.S. and Europe would probably have accelerated renewable energy deployment even more (and / or kept more nuclear power plants online).

The next leg down in U.S. emissions

All else equal, higher natural gas prices improve the environment for renewable energy growth. Last year, when natural gas prices spiked after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, countries across the world doubled down on renewables. The U.S. and now the E.

Still, we often ask ourselves just how significant growth in solar and wind in the U.S. will be over the next decade. Time to make some hypotheses!

For insight, I turned to modeling and analysis from Enersection. The Enersection team took time late last year to forecast power generation changes on a state-by-state basis after the passage of the IRA. Using annual renewable subsidy spending forecasts from the Congressional Budget Office, Enersection estimated baselines for wind and solar generation growth. The team then used these estimates plus overall demand growth to calculate coal and natural gas displacement.

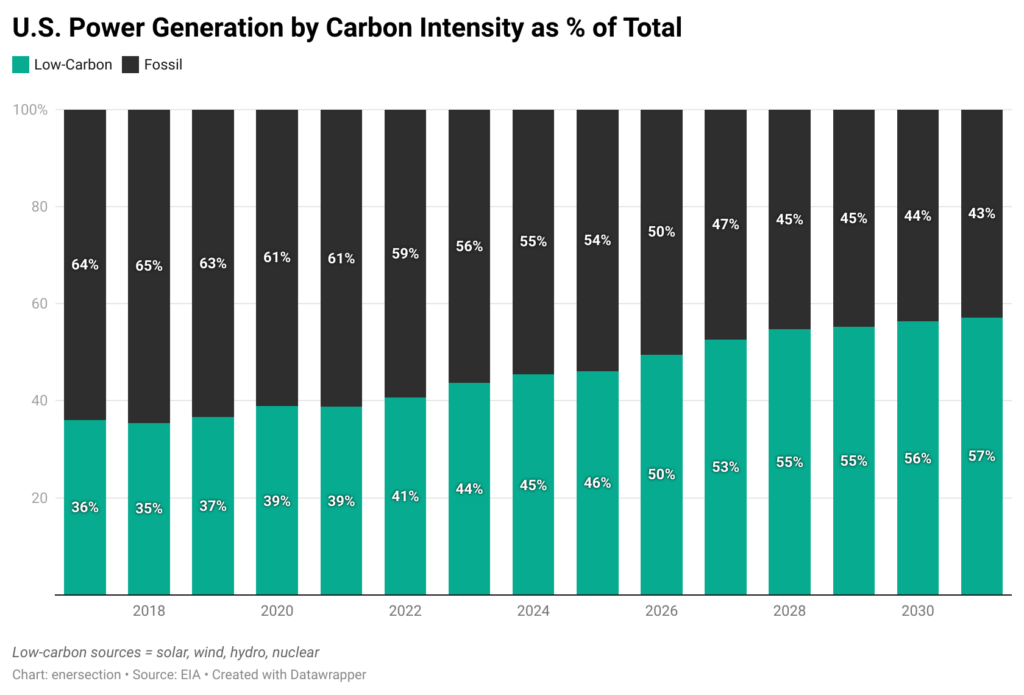

Let’s dive into some conclusions. At the top-level, Enersection shows low or no-carbon generation sources will represent 57% of U.S. power in 2031, up from 41% in 2022. Solid progress! … but also not earth-shattering.

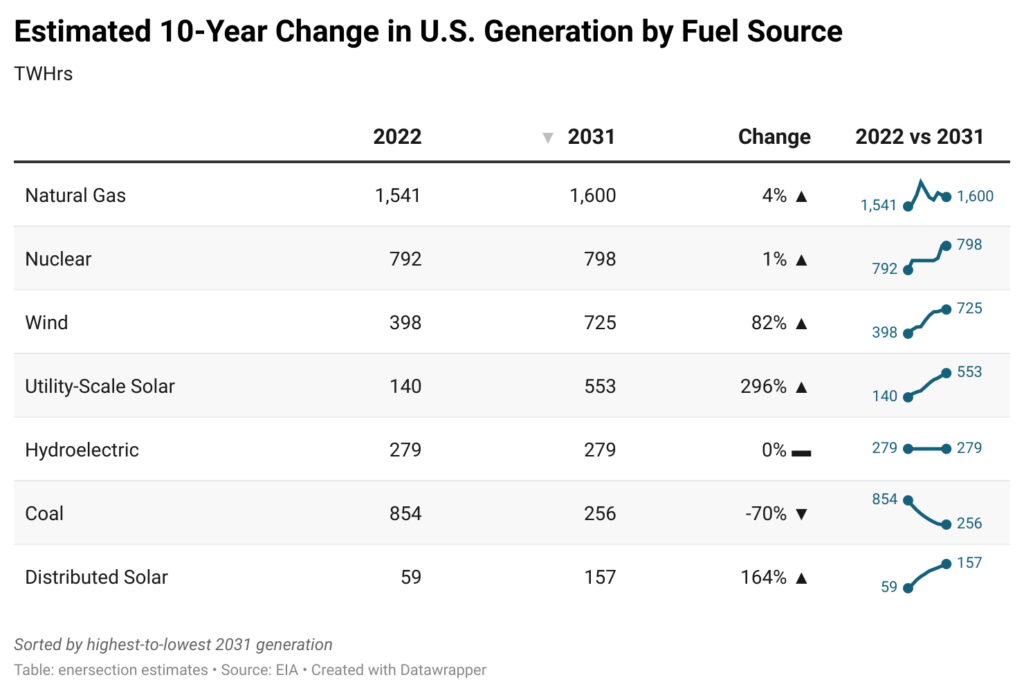

Of that, ~33% is from fuel-saving renewable energy sources, like solar and wind. A substantial share (~24%) is supplied by hydroelectric and nuclear power. That said in the next chart, you’ll note there’s little to no growth in hydro and nuclear. While some states, like Washington, run largely on hydropower, they’ve already used up the best sites for dams. And on the nuclear front, you’d need to be building a reactor yesterday for it to generate electricity in 2031:

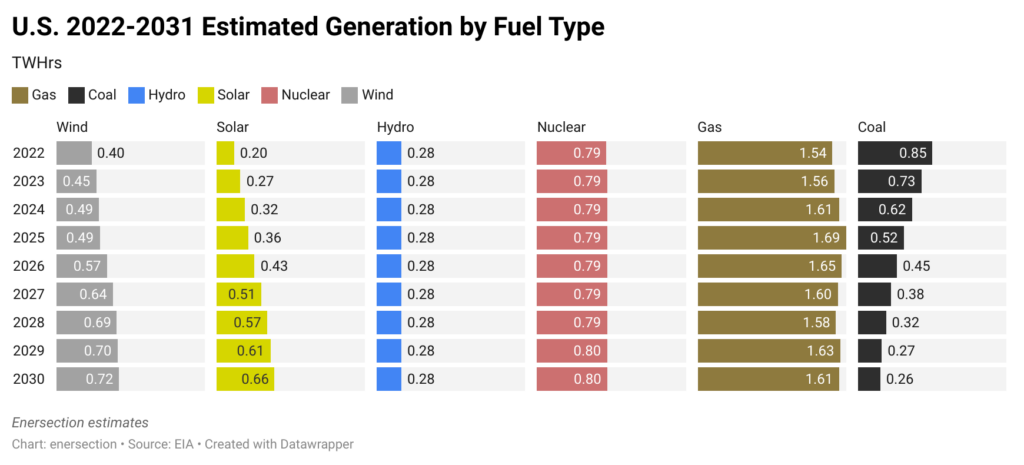

All of which is to say that all the growth in low-carbon sources will come from renewables. Another way to contextualize this is in aggregate generation:

While the growth rates in renewable energy here are tremendous, the forecast stickiness of natural gas is also noteworthy. The story of the past decade has been displacing coal with natural gas. The story of the next decade looks like it will be replacing coal with renewables, with little change to gas generation.

Part of the reason for this is gas’s status as a dispatchable fuel source. It’s easy to fire up natural gas plants quickly if and when demand spikes. Contrasting that quality with the variability of wind and solar, and absent growth in nuclear, hydro, or massive improvements in energy storage, full U.S. grid decarbonization isn’t on the near-term horizon.

Don’t despair, though. A 70% reduction in coal use from current levels will do wonders to reduce U.S. emissions and air quality.

States of the nation

So, where will a lot of this growth take place? For one, we’ll get significant follow-through in states like California and Texas, where the renewable energy bonanza is already well underway.

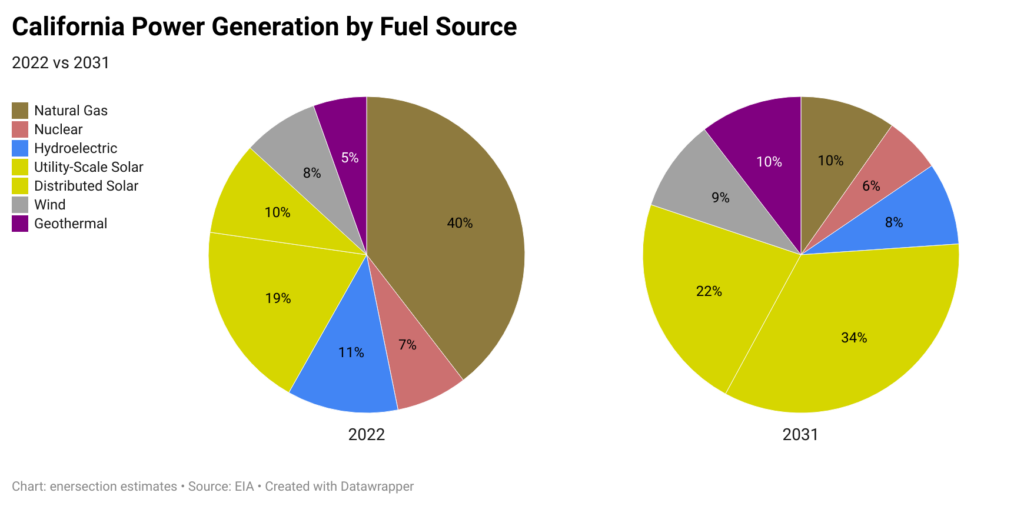

Enersection projects ~90% of California’s in-state generation will come from low-carbon sources by 2031:

While natural gas is sticky in power generation at the national level, the story in California looks pretty different. Solar, both utility-scale and distributed, is going to go absolutely bananas. As a note, in the modeling, solar includes battery storage capacity charged with solar during the day and discharged later. By leading on the battery energy storage deployment front, California should be able to reduce its natural gas dependence significantly.

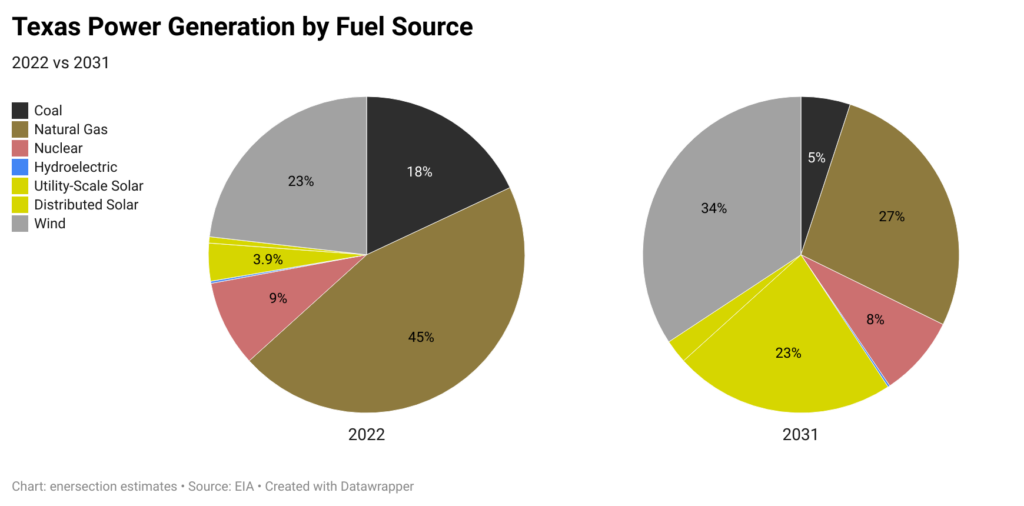

Let’s turn our attention to Texas, the one state in the union with its own grid. You’d be hard-pressed to find many Texas energy folk talking about climate change. Still, Texas has deployed a ton of renewable energy capacity in recent years and has halved its coal consumption since 2010. Wind in particular has been a powerful growth area in Texas; West Texas and the Gulf Coast are in many ways, the wind power capitals of the U.

And while Texas’ renewable fleet is already impressive, Enersection sees Texas’ renewable energy capacity and generation continuing to expand dramatically over the next 8+ years.

While not quite as dramatic a reduction in natural gas’s share as in California, by 2031, Texas will have almost eliminated coal use and cut natural gas use a lot. Further, the fact that wind could be its largest single power source, with wind and solar together handily trumping natural gas and coal, is remarkable.

Of course, many other states, like Louisiana or Delaware, to pick on a few, will develop very little renewable energy capacity and will continue to rely on natural gas for most of their power generation. Hence why natural gas will still be king on the national level.

EV penetration

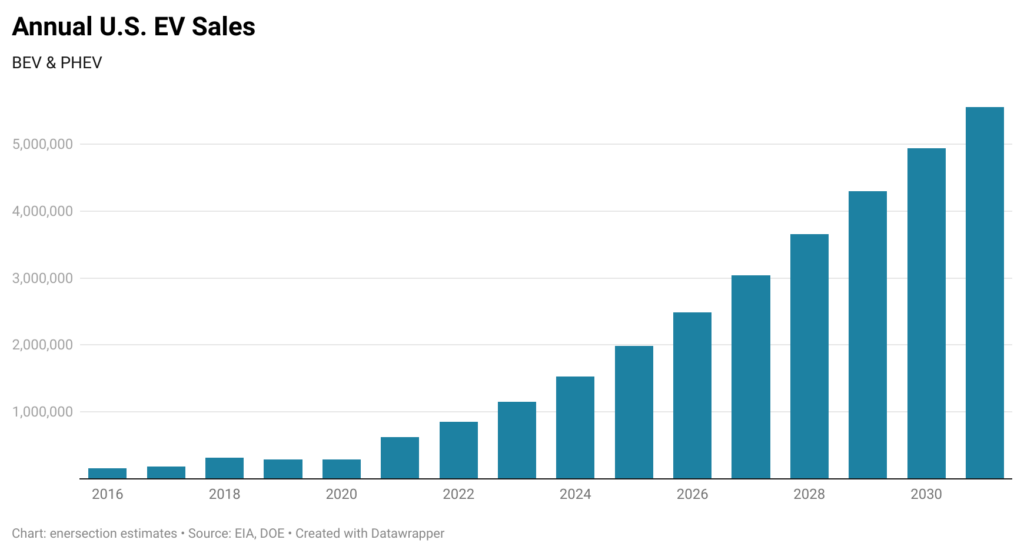

Beyond the question of power generation, I also dug into Enersection’s modeling on the EV front. As we’ve noted a few times this year, global EV sales comprised north of 10% of new car sales last year. The next question is whether that’s a tipping point – i.e., a threshold that once crossed ushers in exponential growth – or whether growth will continue more linearly.

The IRA’s incentives for EVs, and the wave of domestic EV battery manufacturing investments it ignited, are poised to spark significant growth in EV sales in coming years. Based on Enersections’ modeling, annual EV sales in the U.S. (EVs + plug-in hybrid electric vehicles) will expand ~5x+ by 2031.

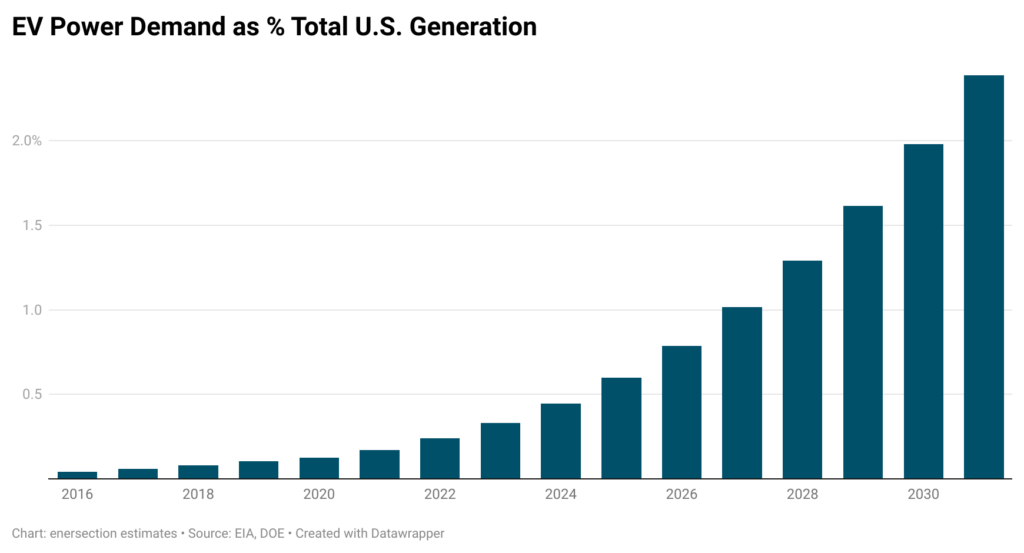

This growth in the EV fleet will (surprise) also start to tie back into power generation. Demand from EVs will start to play a meaningful role in demand as EV sales scale. In case all the fundraising for EV charging infrastructure stands out to you any given month, the below helps explain why that’s so hot:

2% might not sound like much. But it’s actually quite staggering to think 2 of every 100 electrons supplied to the grid will be used to charge EV batteries.

Nor will that additional demand just mean a growing pie for EV charging providers to slice up. It will also strain the U.S.’s already strained grid. Upgrade costs to accommodate more charging and other electric appliances, like heat pumps, will become a larger talking point this decade. As an aside, protests in Boston this month show just how hard it can be to build a single substation without angering local stakeholders.

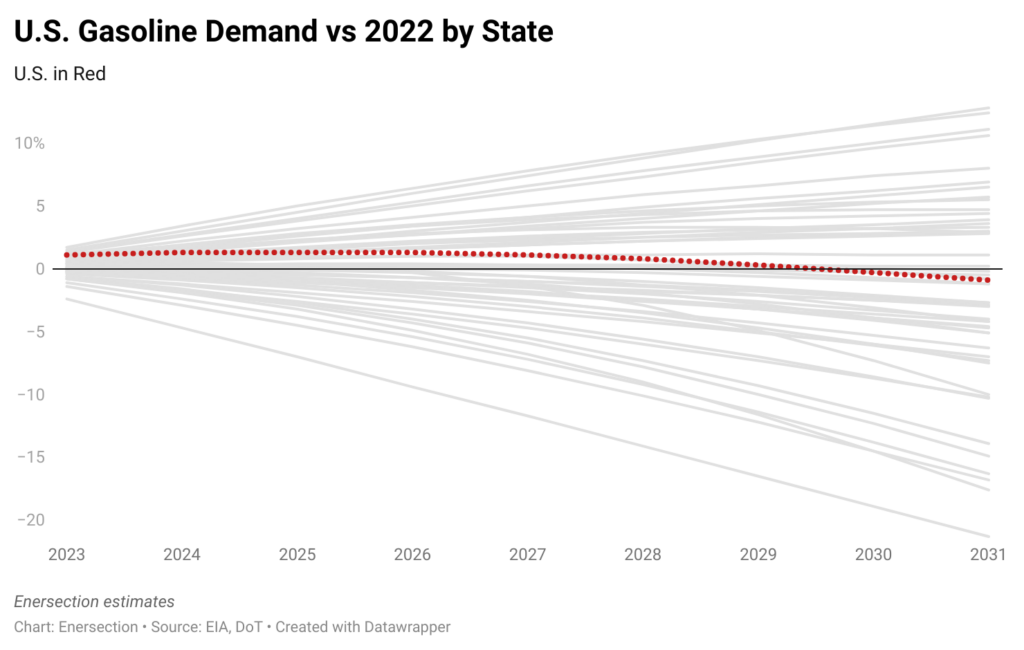

What does this portend for U.S. oil demand? Not all that much in the near-term, unfortunately:

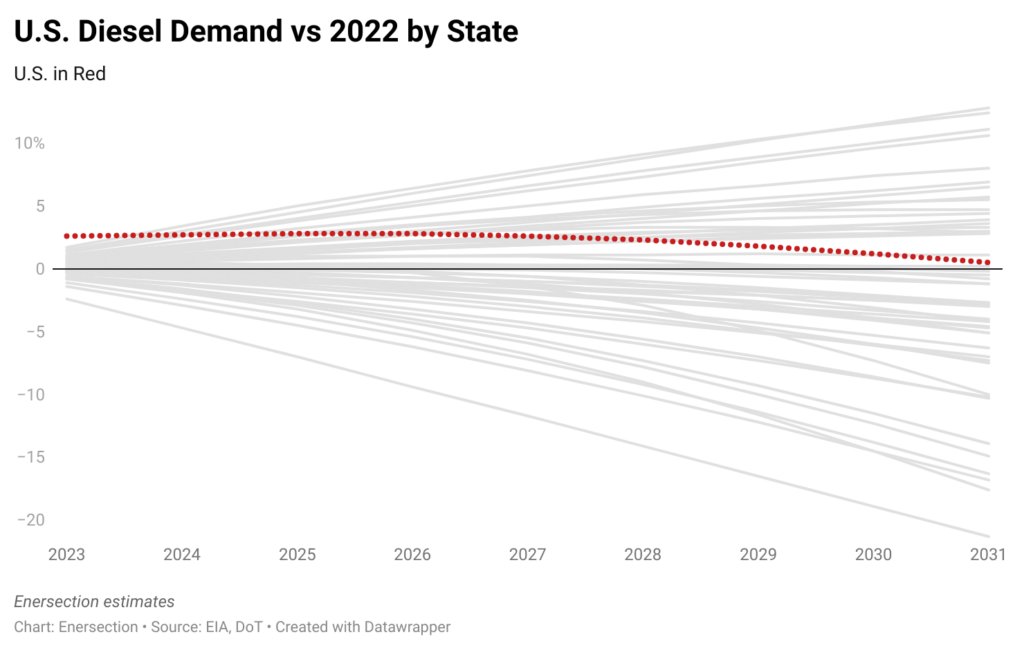

Even as the U.S. EV fleet expands, and absent other breakthroughs, gas demand will only start cresting down slightly in 2031 (with significant variance by state). Similar story for diesel, the workhorse fuel for trucks and trains:

While technologies like Range Energy’s electric trailers (compatible with both electric and diesel-powered tractors) might help curb diesel use once they’re out on the market, the long road to electrification for 18-wheelers means diesel demand might not turn negative until a decade from now.

The net-net

The tricky thing with S curves is that it’s hard to tell when you’re on them. In another ten years, we may look back at the current adoption rates for technologies like solar, wind, and EVs as quaint. And we may look back on the IRA fondly as a critical inflection point followed by meteoric growth. I’m optimistic and would put my chips on that — hope springs eternal!

That said, it’s also prudent to take stock of the headwinds that could slow tech deployment, many of which we explore week in and week out:

- Supply chain and material cost challenges for wind turbine manufacturers

- Trade restrictions on solar panel imports

- Constraints to metal and mineral supply for batteries

- Long interconnection queues, permitting reviews, and high costs for new generation in the U.S.

It’s also best not to overstate the progress we’ll make in 8-10 years. The U.S. grid won’t fully decarbonize over that time frame. It won’t even get close. That’s not a reason to despair — emissions reductions may well still be steep.

Many thanks to Enersection for letting me review and present all this. You can explore their report here if you think their forecasts could be valuable for your business or research. And if you’re interested in using the full forecast model, take a look here and reach out to the team.