05 January 2023 | Climate Tech

Hot or not?

By

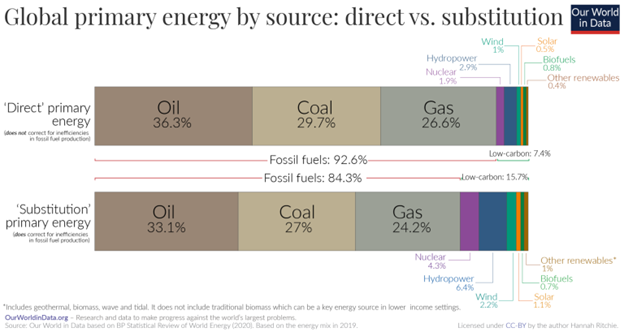

Before we dive into an assessment of what’s hot and what’s not across climate tech and energy, reframing ‘the goal’ is always worthwhile. Entering 2023, 80%+ of the world’s primary energy (which includes electricity, moving things around, and generating heat for industrial applications) comes from fossil fuels.

Oil, coal, and gas are by far the most common fuels globally for generating energy. Oil is combusted in engines to move things around. Coal is burned in power plants or used in industrial processes like steelmaking. And natural gas has made massive inroads over the past few decades globally in power plants, in various industrial applications and, in some cases, transportation.

Viewed from this lens, the progress of low-carbon energy sources looks paltry. This speaks to the challenge; the world’s low-carbon energy supply must expand massively before greenhouse gas emissions meaningfully fall.

Unfortunately, global emissions are perhaps the hottest trend in this newsletter; CO2 and methane emissions still increase every year, as does demand for coal and oil. That’s also why exponential growth rates for clean energy tech and other technologies like EVs are critical.

Against that backdrop, let’s explore what solutions are trending up and down.

What’s hot

Solar continues eating the world

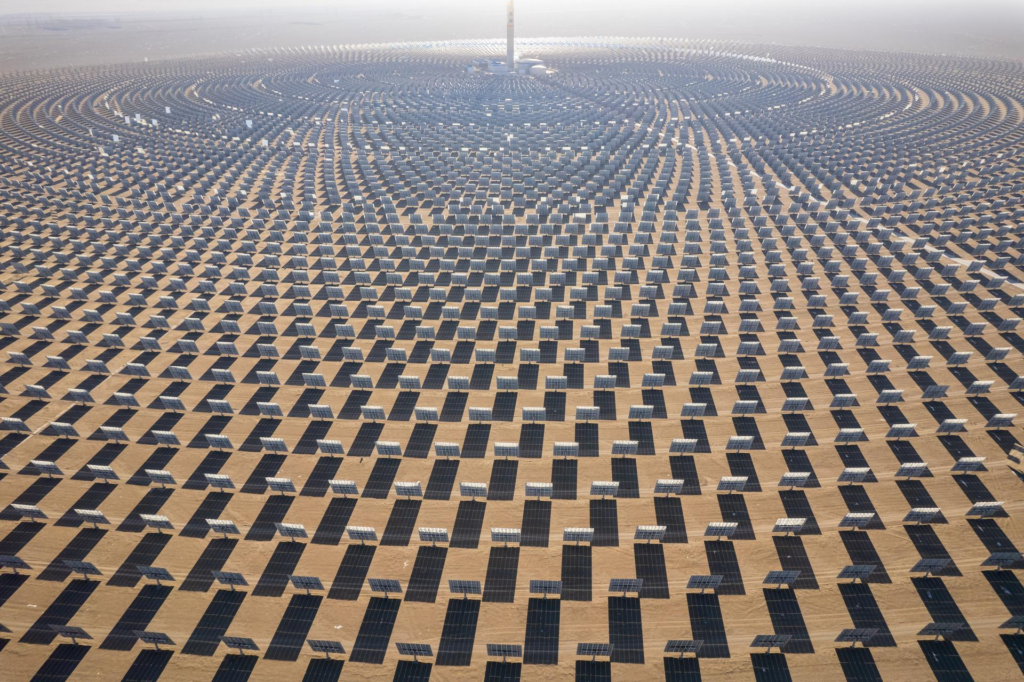

In 2023, solar will continue to ‘eat the world.

In 2023, solar capacity should grow by another 30-40%. Last year, total installed solar capacity first eclipsed the 1 TW threshold, and we should see 300 GW+ of capacity additions this year, buoyed by falling costs as Chinese manufacturers continue cutting prices.

While visions of rooftop solar on homes may come to mind when reading this, China is far and away the leader in new solar capacity additions. Growth in Europe and North America is also a significant contributor. Notably, the U.S. may lag, as investigations into tariff circumvention and ensuant import restrictions complicate sourcing panels from China.

The present clip of solar installations is strong but needs to be sustained, if not increased, for many years. In 2022, solar accounted for roughly 4% of global electricity generation. More 30-40% growth years are necessary to get that number to double digits. At some point, that will depend on expansion into new markets, e.g., Africa and the Middle East, too.

Exponential EVs

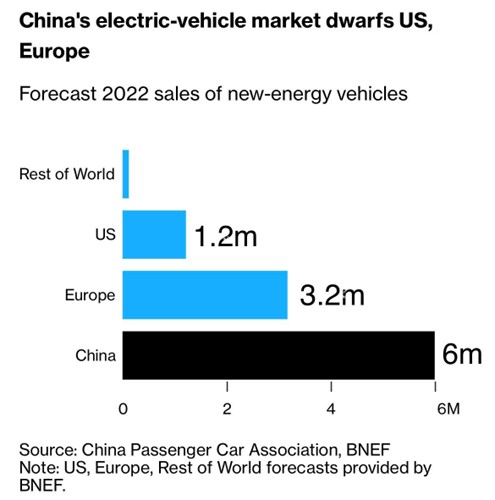

Though they’re not without negative impact, EVs are far better for the environment than combustion engines that run on gas or diesel. And growth rates and market penetration for EVs are also taking off exponentially; EVs now command north of 10% of new car sales globally, up from less than 5% in 2020.

When you think of EVs, you may think of Teslas in Silicon Valley. But as was the case with solar above, China is the global leader in total EV sales. Other markets feature a higher EV share market (e.g., Norway, where EVs are 80%+ of sales), but these are tiny overall markets, comparatively.

Alongside growth in EV sales, massive investments in new supportive infrastructure, whether charging stations or grid upgrades to support more load from said chargers, are both necessary and flowing. One sub-sector worth focus in coming years is how EVs, their chargers, and their batteries integrate into the grid. For instance, there’s ample opportunity to coordinate resources and use EVs for more than transportation as vehicle-to-grid technology matures.

Talent

Alongside the deployment of solar and EVs, the wellspring of talent that wants to help deploy climate solutions and work for climate tech firms is incredibly strong.

Anecdotally, the firms I chat with note they receive many strong applications these days. And the job seekers I regularly engage with say the climate roles they’re applying for are highly competitive.

Whether or not you think the funding boom for climate techs will withstand a recession, this is a boon to firms that have already raised and are hiring.

Price catalysts

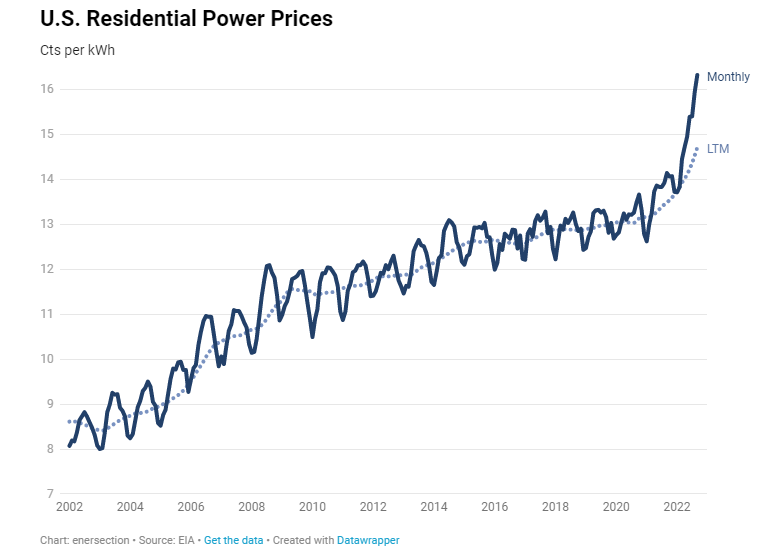

Crises are often the perfect catalysts for innovation. Few things are better at accelerating tech deployment than a good ol’ economic incentive. Nor is it just Europe where an energy crisis (and warmer weather) is driving reductions in energy use and policy focus on energy efficiency. Electricity and heating prices in the U.S. have never been higher either:

2023 should be a great year for solutions and firms focused on energy efficiency and fuel economy as a result. While new supply-side solutions, like a new fuel source for transportation, are often more expensive for some time, any technology that unlocks greater efficiencies and saves fuel or energy starts paying itself off right away. Areas I’m watching closely in energy efficiency include:

- Building energy efficiency (see AeroShield, Flair, Calumino)

- Efficiency solutions in transport (see RailVision Analytics, TOffeeAM, rouvia)

- Mitigating food waste (see Apeel Sciences, Afresh)

What’s not

Headwinds

While analysts expect total renewable energy capacity expansions in 2023 to come in as high as 500 GW, as we covered in ‘what’s hot,’ the majority will come from solar. Wind, whether onshore or offshore, continues to grow but faces headwinds.

For one, many wind turbine manufacturers aren’t making money, as they struggle with higher input costs and Chinese competition. And while incentives abound in places like the U.S., getting all stakeholders onboard for new development can be difficult.

Wind will continue to see solid growth in 2023, but not at the rate we’d hope. 2020 was a record year for wind capacity additions; 2021 saw installations decrease some 30%, and 2022 didn’t see a full recovery to past levels. 2023 likely won’t, either.

Similarly, there’s a whole class of other renewable energy sources like geothermal and tidal / wave energy that have yet to take off as much as wind and solar. Geothermal gets some attention, but its footprint remains small outside of places like Kenya and Iceland, which are endowed with ideal geology. Harnessing tidal and wave energy feels all but forgotten at times. Those are critical innovation areas as they represent opportunities to supply power around the clock, rather than 25-35% of the time, like solar and wind.

Err-SG

Another climate tech area that’s taken it hard on the nose of late and is still struggling to get up off the mat is the entire ESG complex. In 2022, ESG somehow became a meme that anti-‘woke’ politicians, especially in the U.S., latched onto and derided.

ESG has become a moniker that subsumes so many different products and strategies that it’s perhaps not surprising the term has lost some usefulness. And that’s the problem. ESG as a practice, i.e., investing that considers environmental and social impact in addition to financial analysis, is going nowhere. Unfortunately, whether or not an investment vehicle has ESG in its name tells you little about what analysis is being performed.

The damage to ESG investing may be more reputational at this point than visible in things like fund flows. Still, like the carbon credit market, many people, including ardent climate and environmental supporters, have come to mistrust the ESG term. The ESG industry needs a rebrand or to prove its worth via a few key wins to regain its footing.

Tossups

The nuclear question

Nuclear energy had a mixed year in 2022. It has many vocal proponents. And it scored some key wins:

- New reactors went online in places like the UAE

- Private firms scaling next-generation reactors reaped big investments

- The Diablo Canyon power plant in the U.S. got a new lease on life

At the same time, plenty of countries are moving away from nuclear energy. And building new plants remains time and capital-intensive. If you want to generate new electricity via nuclear in 2030, you better be building your reactor already. China is also leading the charge on this front, with far more reactors actively under construction than any other country.

How the rest of the world zigs or zags still hangs in the balance and depends on several factors. Policy and public opinion are two that are shifting favorably after a decade-long slide post-Fukushima. The biggest driver may be the cost of other energy sources. One reason the U.S. stopped building reactors, for instance, was the increased cost competitiveness of natural gas, domestic production of which has skyrocketed in the past thirty years.

The investment calculus in building a new reactor differs greatly from other low-carbon power plants. Unless they’re operating on a much longer time horizon, considering grid balancing benefits, or betting on small modular reactors, most developers will opt for wind or solar, which have gotten much cheaper since nuclear’s heyday.

Removal realism

2022 was the biggest year for the carbon removal industry by a wide margin. It’s hard to see interest in carbon removal slowing down this year. And I expect the market for carbon removal credits to expand significantly in 2023, although that’s saying little, considering how small the market is at current.

Now that carbon removal is on the map, things may get more challenging as the rubber meets the road. Many firms are navigating the transition from the lab to the field. That transition inevitably comes with challenges across technology, measurement, or even things like getting government permits. If enough firms struggle to scale their removal capacity, you’ll see some disillusionment from investors and corporate buyers, whose delivery dates for pre-purchased credits may inch backwards.

I wouldn’t characterize this as a case of Icarus flying too close to the sun. Based on the current carbon removal capacity, Icarus has yet to even get off the ground in this metaphor. 2023 probably won’t feel as high flying for carbon removal as 2022 did. Maybe that’s a healthy dose of realism.

Friend or foe?

China is a calling card for people who doubt climate tech makes an impact. They point to new coal capacity additions in China or its status as the #1 CO2 emitter.

Both are true, but China’s relationship to climate tech is much more nuanced than that. As we explored, they’re the global leader in solar installations and EV sales. Overall, they deploy more renewable energy (including more offshore wind than the rest of the world combined).

They manufacture most of the world’s solar panels and control a significant share of the metal refining capacity necessary for battery materials and other critical components of electrification.

On the one hand, if the rest of the world is going green, why wouldn’t China want to sell to and supply them? In that sense, China plays and will continue to play a hugely complementary role in the energy transition and climate technologies.

On the other hand, I’m no expert on what the CCP thinks about climate change, low-carbon energy, and the decadal climate policy outlook in China. Outside of their 2060 target to use 80%-non fossil energy sources and a 2030 target for ‘peak’ emissions, I think their top priority is energy resilience and independence, regardless of fuel source.

Either way, China and the rest of the world’s relationship with it will remain hugely influential to climate tech for years, even as India overtakes it as the world’s most populous nation.

Climate funding: Boom or bust?

I expect the funding environment for climate tech firms to remain strong in 2023. Especially compared to other sectors. Still, we must acknowledge that the overall fundraising environment is much different than at the beginning of 2022. And numbers may be down year-over-year in 2023 compared to 2022.

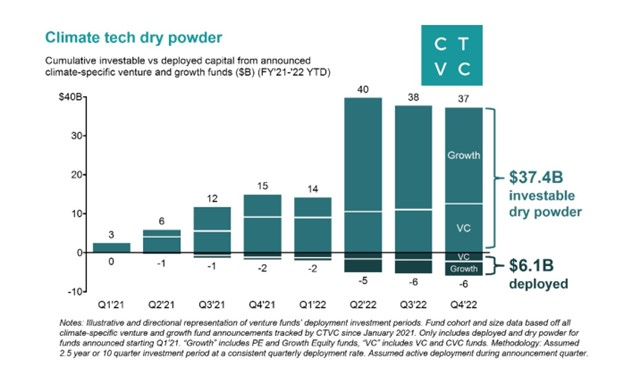

That said, investment firms have lots of cash to invest in climate solutions. And many investors are raising new funds to focus on climate solutions.

The bigger risks are not in a near-term slowdown or contraction in funding because of macroeconomics in 2023. It’s if 2020-2022 vintage investments don’t smoothly translate into investor profits later this decade. That depends more on where investors invested rather than whether the world makes progress in mitigating climate change; private funding is often misaligned with the most significant opportunities to mitigate emissions.

I often ask operators and investors what’s different this time vs. the cleantech boom and bust of the late aughts and early 2010s. Late last year many pointed to policy like the IRA. Others say there’s more urgency re: climate change now.

The IRA was definitely a sea change moment. But it’s not enough on its own, and I don’t buy arguments that hinge on the urgency of climate change. We’ve dithered in the face of urgency for decades. All sectors go through cycles of optimism and disillusionment. We’ll see when that time for climate tech comes, and I’ll explore this question more in 2023 with keen interest.