28 December 2022 | Climate Tech

Manufacturing miracle

By

Perhaps the most attention in climate tech is paid to renewable energy and EVs. As well as thornier issues like nuclear power.

That means our attention is often diverted from the lowest-hanging fruit for mitigating climate change. I’m not necessarily saying all of the below is easy. But these are areas where incentives and the right coalitions of stakeholders should align. Let’s take some examples.

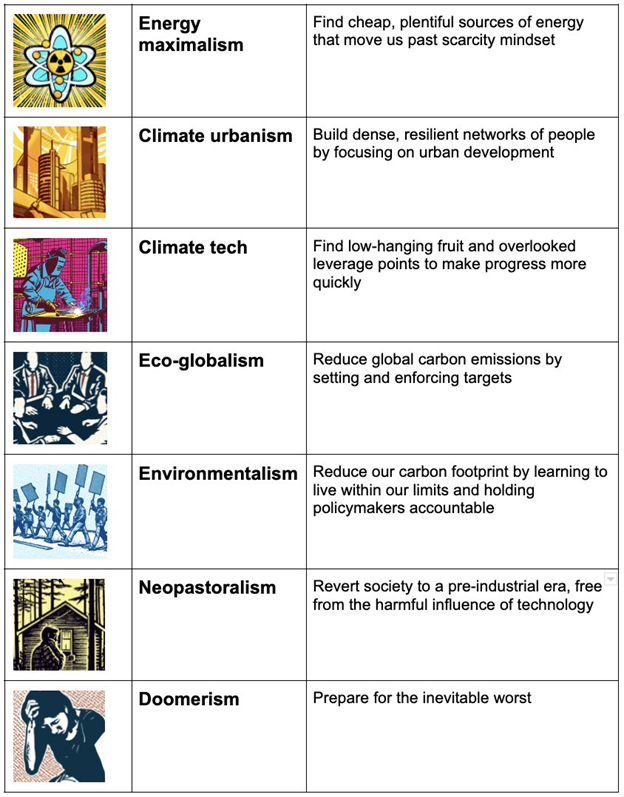

To be 100% honest, I’ve struggled at times this year with something that’s very core to this newsletter, namely, its focus on ‘climate tech.’ What does climate tech mean? Is it:

- Tech that mitigates the GHGs causing global warming?

- Tech that helps humans and other species adapt to climate change?

- Solutions (like software) that enable the deployment of #1 & #2?

Reflecting on how I’ve covered “climate tech” this year, my answer is “all of the above.” And I stand by that. Still, I often crave a more concise and crisp definition for climate tech. And I may have just fortuitously come across it the other day on Twitter:

I like that definition for climate tech a lot. And we have talked about “low-hanging fruit” plenty in 2022 in Keep Cool. We’ve also dipped our toes in ‘Energy Maximalism,’ ‘Eco-globalism,’ and ‘Environmentalism.’ I think everything save for for Doomerism has merit (at least with respect to the word ‘inevitable’).

Looking ahead to 2023, I like the idea of doubling down on low-hanging fruit and leverage points. Framed as a consistent question, where can we best deploy our attention, financial, and human capital?

Battery belt

To carry this idea forward for our last email of 2022, one underappreciated leverage point for climate tech is cultivating bipartisan appeal. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the domestic manufacturing resurgence that public policy and demand for EVs and batteries has sparked in America this year.

If you had asked most manufacturing and supply chain analysts five or even three years ago whether there was a shot in hell that domestic manufacturing would ever recover in the U.S., I think most would have said “no.”

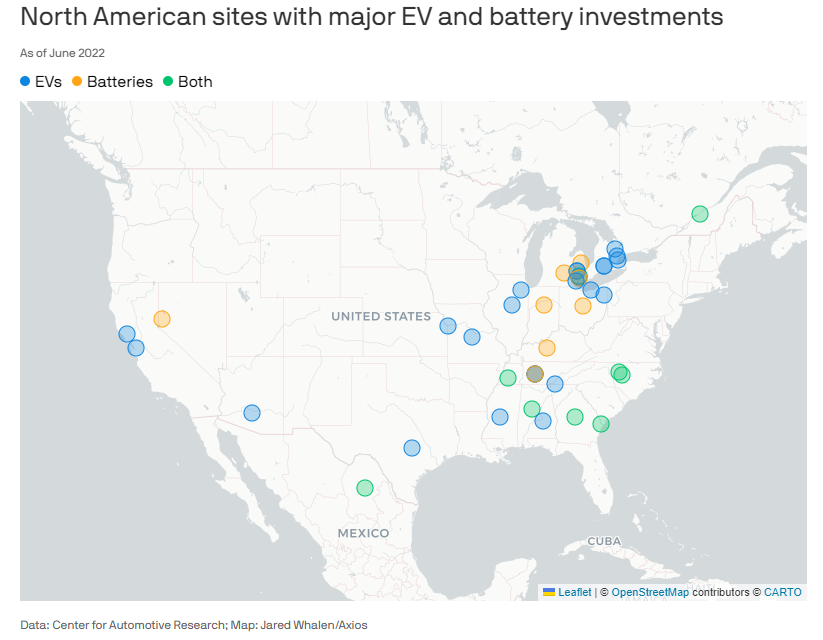

And yet, 2022 was a banner year for new investments in domestic manufacturing, particularly for batteries. Almost every week now comes with a new announcement, investment or initiative. Here’s four from this month:

- 12/22: Form Energy announced $760M investment to manufacture iron-air batteries in an old steel town in West Virginia

- 12/14: Redwood Materials announced $3.

5B investment to build a battery recycling plant in South Carolina - 12/7: American Battery Factory announced $1.

2B investment to build a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) battery factory in Arizona - 12/2: GM & LG announced a joint investment of $275M to expand a Tennessee EV battery manufacturing facility

Manufacturers like Ford, Toyota, and GM have also announced dozens of new EV battery plants this year; total investments in 2022 now likely eclipse $50B.

The Inflation Reduction Act is a big driver behind this battery boom. It established a tax credit of $35 per kilowatt hour (kWh) for domestically produced battery cells, covering roughly 20-30% of the cost of a battery. This, as well as other new policy requirements and incentives, have made domestic manufacturing feasible and attractive again.

Leverage points

EVs are an essential technology to reduce gas miles driven globally and chip away at global demand for oil. Given its role in transportation and industry, oil is still fuel source #1 in global primary energy production. That needs to change

But the domestic battery boom offers more leverage points than that. For one, even within the EV category, there’s remarkable diversity in the types of batteries companies want to manufacture. Lithium is still king, but LFP batteries are a recent innovation that reduce EVs’ dependency on cobalt.

Beyond EVs, some domestically produced batteries will also serve the grid, offering energy storage for low-carbon energy sources like wind and solar. Form Energy’s iron-air batteries omit lithium altogether to create less resource-intensive (and cheaper) energy storage.

And beyond technology, one noteworthy trend is that most new factories are being built in red or at least purple (hotly contested) states. That makes batteries a powerful political lever.

We’ve heard a lot about opportunities to offer old coal workers in Appalachia jobs installing solar panels or wind turbines over the years. Unfortunately, fossil fuel interest groups have successfully fomented opposition to new wind farms and solar power plants in places like Ohio.

But it’s even hard to resist the political allure of a new factory. Factories don’t just come with jobs and economic revitalization. They’re quintessential Americana; many parts of the country were built on heavy industry and manufacturing.

An influx of new factories, which seemed almost impossible last decade, should help convince voters of the value of policies like the IRA and the politicians who advance them. Not one Senate Republican voted for the IRA. Perhaps a few of them are ruing that now.

The net-net

I’m under no illusion that the new ‘Battery Belt’ can fully revitalize all of the old Rust Belt or other areas that declined during the decades when the U.S. mortgaged its domestic manufacturing offshore. But even a few factories in places like West Virginia, Ohio, and the Carolinas, should help score bipartisan points for electrification, climate technologies, and the energy transition.

And while this discussion may seem exclusively focused on the U.S. so far, domestic policy makes waves overseas, too. Other countries also want to score new domestic manufacturing plants and onshore more of their supply chains.

Already, we’re seeing European policymakers fret about falling behind the U.S. in terms of attracting money and jobs for climate tech. Hopefully someday we’ll look back on 2022 — the year of the IRA and significant momentum for climate tech — as the start of a global arms race in the energy & climate transition.