20 December 2022 | Climate Tech

Christmas wish list

By

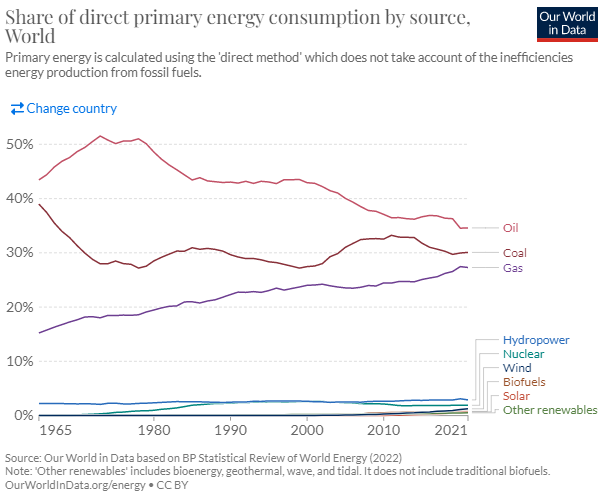

Perhaps the most attention in climate tech is paid to renewable energy and EVs. As well as thornier issues like nuclear power.

That means our attention is often diverted from the lowest-hanging fruit for mitigating climate change. I’m not necessarily saying all of the below is easy. But these are areas where incentives and the right coalitions of stakeholders should align. Let’s take some examples.

Not wasting natural gas

While ‘decarbonization’ is the drumbeat of climate conversations, CH4 (methane) is a 30x more powerful global warming agent over a hundred year timespan. And natural gas, the primary fuel used to produce electrical output both in places like California and oil-rich regions like Qatar), is mostly methane. I’ll use the two interchangeably.

One positive is that when you combust methane, i.e., burn it to produce heat in a power plant, it produces less CO2 than coal. Natural gas plants are also more efficient than coal-fired ones. Combining efficiency gains with cleaner combustion, natural-gas plants produced ~half as much CO2 compared to coal.

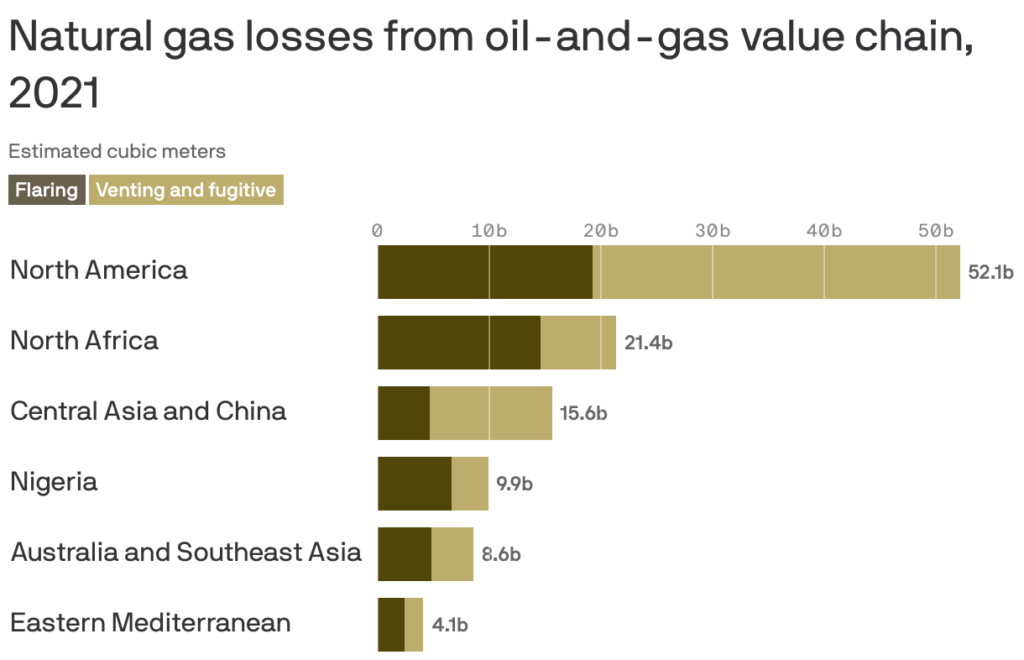

Here’s the problem. The world wastes a lot of methane and natural gas, even though prices for natural gas have skyrocketed this year (in part because of Russia’s brazen invasion of the Ukraine). Particularly in the oil & gas industry, a lot of methane that could be used is wasted and simply vented off into the atmosphere. Sometimes it’s flared, which means it’s burned instead of vented. This is better (remember combusting methane produces less CO2 than coal) but isn’t 100% efficient. Even when flaring, some methane still escapes into the atmosphere and accelerates global warming.

Why do we waste so much natural gas? Part of the answer is that legacy oil wells weren’t set up to do anything with the natural gas that builds up inside them. They were set up to get oil, not the gas that often accompanies it underground. Firms could pipe it and sell it. But that’s never been the practice, and would require new investment and infrastructure.

If ever there were a time to do something about that now, however, it’s now. A confluence of tailwinds makes change more likely. For one, there’s legislative pressure on oil & gas companies to clean up their act. In North Dakota, straight-up venting is already illegal. And there’s global alignment on reducing methane emissions across the board.

To be sure, methane vents into the atmosphere from many other sources, whether landfills, cows, or natural systems. Nor am I suggesting oil & gas companies have always ‘played ball’ in this area. Still, areas with existing oil and gas infrastructure are the perfect place to start.

Further, considering price increases and global demand for natural gas, there’s an economic incentive to recapture rather than waste it. Some firms, like Crusoe Energy, have built successful businesses diverting methane from the atmosphere into monetizable applications. You can read more about their process here from us.

A top priority for mitigating climate change should include a working coalition of private companies, policymakers, and oil & gas companies attempting to keep as much of this wasted methane out of the atmosphere as possible. Earth observation data and LiDAR tech is already advancing significantly to help with monitoring and leak identification. Wasting less methane is good for the atmosphere, good for energy security, and good for companies’ bottom lines!

Coal-free stockings

At our happy hour last week, someone asked me whether it’s hard to process information about climate change constantly and whether I get disillusioned at times. The answer is definitely. Specifically, there are some core beliefs that I’ve had to change my tune on as I learned more this year. One is whether a grid based purely on renewable solar, wind, and batteries is feasible.

To be sure, it may be someday, but even most grids with 30-40% penetration from solar and wind still feature heavy support from natural gas (or coal). Wind and solar aren’t highly ‘dispatchable,’ which is a fancy way of saying they don’t produce electrical output all the time. And there isn’t a sufficiently sophisticated long-term energy storage solution to pair with them to make their electrical output available 24/7.

People argue about this and what it means a lot. But I don’t think we need to, at least not yet. At the minimum, solar and wind are fantastic fuel-saving technologies. Add them to the grid, and you can save a lot of natural gas and coal, saving emissions and money.

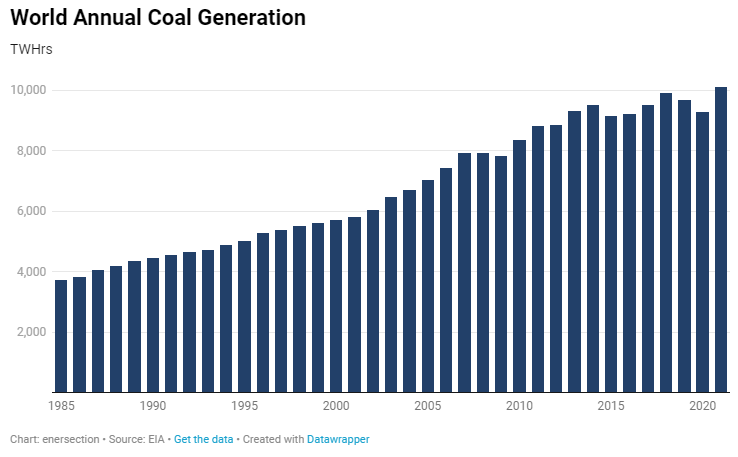

Nor should arguing about how to build a grid with higher rates of solar and wind penetration even be our highest priority. The highest priority on electrical grids should be phasing out coal.

Coal is the dirtiest and the most common fuel used to generate electrical output globally. Believe it or not, even as 2022 was an awesome year for climate tech and we’re two decades into environmental and climate movements, the largest single share of electricity generation globally still belongs to king coal.

No kid wants coal in their stocking for Christmas. And I’d like to see a faster transition away from coal on grids. Whether in the U.S. or the developing world, transitioning off coal power plants is one of the best ways to mitigate climate change. That can be accomplished in a number of ways, whether via the fuel-saving technologies we discussed (solar and wind), new nuclear fission power plants, or transitioning to natural gas power plants.

It might seem strange for a climate tech guy (me) to argue for building natural gas power plants, but I’ll swap a coal-fired plant for a natty gas one any day of the week. Natural gas plants are cleaner, and they can be built to be highly dispatchable, which means they pair well with solar and wind capacity as more of that capacity comes online.

In any case, to make a difference at the global level, more agreements like the one recently announced that will see countries like the U.S., the U.K., and Germany provide $15B+ to Vietnam to transition off coal are tremendously important. Similar agreements are in place for Indonesia and South Africa.

Let’s hope our governments pay up and do even more elsewhere. Including at home; there’s plenty of coal-fired capacity in countries like Germany and the U.S. to retire, too.

The U.S. has made progress; more than 50% of electricity in the U.S. came from coal when Obama took office. Now that number is down below 20%. Germany hasn’t had as much success; especially this year when Russia cut off their natural gas flows, they’ve resorted to burning a lot of coal, often one of the dirtiest forms of it, no less.

Ideally everyone can follow the U.K.’s lead; the Brits are on track to phase out coal entirely by 2025, thanks to an impressive wind fleet, interconnectors to Europe, and natural gas capacity.

Cooking clean

No, I’m not talking about counting your macros and eating healthy. Nor is this one exclusively a climate change challenge. Other statistics associated with it are even more striking. Almost a third of the global population doesn’t have steady access to clean cooking. In some parts of the world, a leading cause of death is use of wood or other dirtier fuels in homes to cook. The impact of doing that regularly is disastrous for human health.

Expanding access to cleaner cooking fuels, let alone electricity, should be a top priority even before climate change enters the conversation. Further, transitioning communities off burning biomass for cooking would also be great for the climate. Cooking fuels translate into greenhouse gas emissions across a number of pathways, whether from deforestation to source the wood or combusting the wood or other biomass itself.

Effecting a transition to cleaner cooking fuels will be no small feat. Philanthropic efforts are a good start, and carbon markets are increasingly expanding classifications for carbon credits sourced from clean cooking fuel initiatives. If this works, it’ll be carbon markets at their best, namely, a means to reduce emissions and finance a solution in a developing country that has all kinds of co-benefits (economic empowerment, health, etc…)

Still, I’m unsure whether carbon credits tied to clean cooking stove initiatives are the best solution – it’s the early innings here and we’ll see how it plays out. Developed countries paying developing countries, the same way they’re paying Vietnam to transition off coal, also comes to mind. Maybe there are other innovative business models to apply here that no one has thought of yet. Food for thought for all you entrepreneurs over the holiday break!

Expanding access to electricity would also help with this challenge (not to mention countless others). To this end, several firms are building microgrids in Africa, where there are plenty of opportunities for distributed solar projects or other set-ups that don’t require grid expansion or significant capital investment. That’s unlikely to solve the challenge on its own. Regardless, this is an opportunity area that shouldn’t go by the wayside.

The net-net

It’s unlikely these are the highest priority wish list items you’d spot in other climate newsletters. And it’s not because I’m trying to be contrarian (okay, maybe a little). It owes more to all the focus I already see on expanding renewable energy and EVs and the wave of public policy support and spending those technologies have garnered this year. Those technologies are already well-positioned to become dominant forces in energy and transportation in the coming decades. It’s our job not to lose sight of other opportunities.

The ones we explored today have significant potential to mitigate global warming, not to mention other societal scourges. Nor is it an exhaustive list by any means. I’d love for you to make your own list and email it back to me! Curious for your thoughts.