06 November 2022 | Climate Tech

Deadbeat COPs?

By

First, some good news. Brazilians elected Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (“Lula”) last week. As you may well have seen, analysts heralded his election as good news for the climate. Amazonian deforestation accelerated under his conservative predecessor, Bolsonaro.

The Amazon is the most symbolic and well-known of all the world’s ecosystems and terrestrial carbon sinks. Unfortunately, deforestation and global warming have diminished the Amazon’s ability to act as a buffer against additional CO2 emissions.

Slowing deforestation in the Amazon won’t exactly reverse climate change, but it’s a crucial mitigative step to prevent further harm. Nor will it be easy, though Lula has made it one of his early platforms post-election. Hopefully, he delivers. As a note, his politics in other areas are far from uncontroversial; I’m covering the climate side of things here, not making any endorsement.

Deadbeat COPs?

Lula’s plans tie into the next climate and policy headline that will dominate media coverage for the coming weeks, namely COP27, the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference.

Securing funding for Amazonian conservation is one of many discussion points that will come up at the conference. Other topics of conversation will include whether climate targets are effective as well as who should pay for climate change’s damage.

On the first point, scientists and industry analysts have changed their tune in recent months, admitting that the 1.

This reality also calls into question whether targets like this are good communication strategies. Every millionth of a degree technically matters; big round targets risk discouraging people when they become impossible to hit. Similarly, a vision of a better world would probably be a better value proposition for people vs. apocalyptic analogs (I have the same bone to pick with political candidates in the U.

On the second point, the conference is in Egypt this year. Africa is ground zero for climate change. A conference on the continent will rightly focus on who should cover the ballooning costs of climate change. Droughts are already decimating parts of Africa. And elsewhere, flooding in Pakistan this year brought home that these concerns aren’t theoretical; they’re here now. Some derivative questions include:

- Should countries that have pumped the most greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere foot most of the bill?

- If so, how should governments structure climate payments or climate ‘reparations’?

- Should developing countries have to forego the economic benefit of burning fossil fuels?

- Should they be paid to do so?

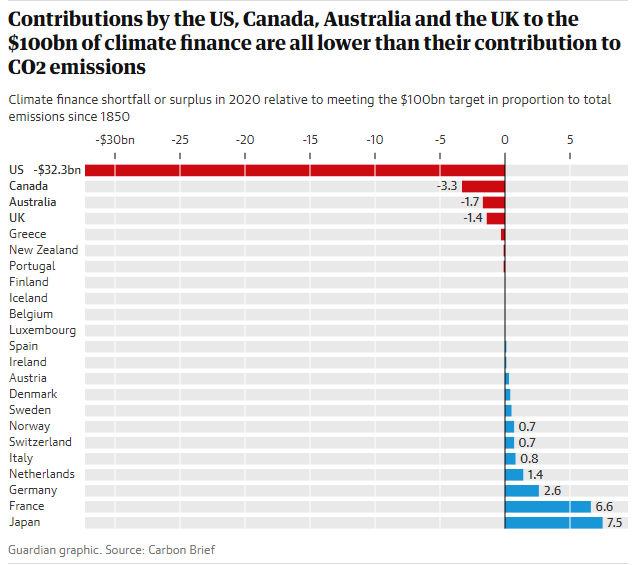

I’m not holding my breath for any miracles at COP27. I reckon plenty of important networking goes on, but most of the stuff that makes headlines hasn’t traditionally led to action, at least not yet. For instance, in 2009 rich countries pledged $100B to combat climate change. Here’s how that’s panned out, with countries’ contributions and shortfalls weighted by historical CO2 emissions.

The least charitable opinions about the conference aren’t even that it’s a distraction from getting work done. It’s that COPs are a ruse for countries and policymakers to act out progressive intentions before they put off any action for another 50 weeks. Then again, I’m sure some policymakers work very hard to advance important work at COPs. I’ll keep an open mind.

Last but not least…

If you’re in the U.S. like I am, then there’s no way you could have missed that the midterms culminate today, if for no other reason than the inundation of emails and texts asking for your campaign finance contributions.

As we’ve discussed many times, 2022 has been a banner year in the U.S. in terms of public spending on climate technologies. Still, it’d be a shame to stop government support for climate tech now. Opening up the spending spigot alone isn’t enough. For example, a significant buildout of transmission infrastructure for new renewable energy capacity is critical. And the last attempt at reforming permitting laws in the U.S. stalled out more than a month ago.

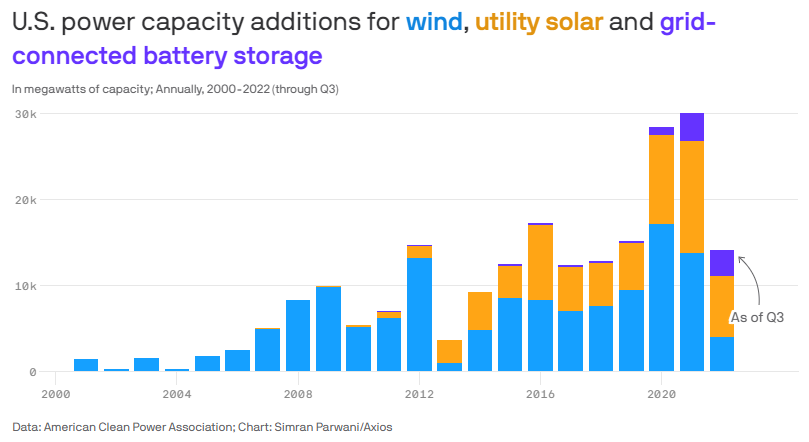

Case in point, Q3 saw a marked slowdown in renewable energy deployment in the U.S., driven in part by higher input costs (inflation) for things like wind turbines as well as by the cumbersome permitting processes renewable energy developers would like to see reformed.

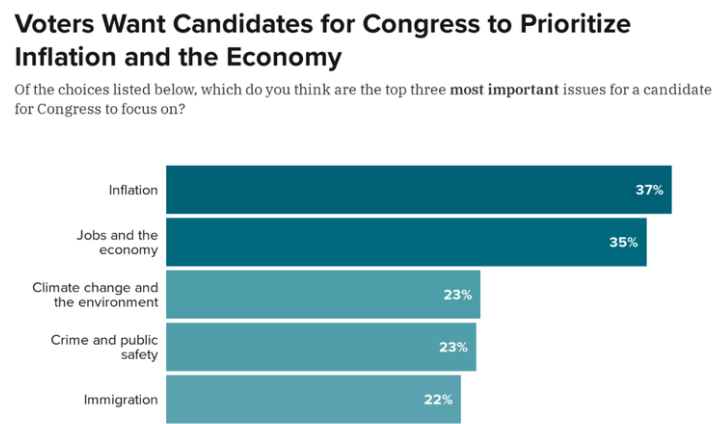

Despite the continued need for more legislation, climate change isn’t issue number one for most voters. Surprise, the economy is. In indirect ways things like energy are important; gas prices seem to be a metric the Biden admin is fixated on. Similarly, inflation is driven in no small part by energy and transportation costs (hence why the Biden admin is prepping $4B+ in payments to consumers to compensate for higher electricity bills). Still, the IRA probably feels like an eon away for most people, if they remember it at all, despite its name as the inflation reduction act.

Conversely, climate change and the environment ranking as issue number three in the polling data above isn’t a bad showing either. But I wouldn’t expect it to come through as a clear motivating issue in this year’s midterms when the votes are counted. People’s focus on the short-term is part of why climate action has been hard to come by in the first place. It’s also very rare that the party that has the presidency doesn’t lose seats in the midterms. We’ll know more in tomorrow.

The net-net

As Michael Birnbaum pointed out in the Washington Post recently, there’s a lot to hang our hats on regarding climate action in 2022. The IRA, as an example, would have seemed like a miracle two years ago (and honestly, did at the time, too). Further, policies like California and Europe targeting no new gas car sales after 2035 would have been headline news for weeks 3-5 years ago. There’s been so much going on this year that I almost missed that news out of Europe. And the recent Brazilian election is another feather in the climate cap.

What’s behind the momentum? It’s rare that five pillars align as serendipitously as they have in 2022 to support climate tech and the energy transition across the world and in the U.S.:

- Global catalysts (climate change, European energy crisis, etc…)

- Public sector investment & legislative support

- Private sector investment

- Consumer demand

- Corporate demand

Still, the scope of the challenges – slowing global warming and re-architecting many parts of society – are so vast that losing any of the above pillars would be problematic. A poor showing for Democrats in the 2022 midterms could topple public sector support in the U.S., for instance.

That’s the irony and paradox of covering something like COP27 and midterms in the same newsletter. It’s easy to point to past COP conferences as examples of the limits of international policy. But at the same time, every election and opportunity is important. So if you’re in the U.S. … vote!