10 March 2022 | Climate Tech

Nuclear doomscrolling

By

I was enjoying some drinks at an investor event in Los Angeles on Thursday night, which meant that for once, I wasn’t scanning Twitter every hour. When I called it a night and took a car across town, I opened the app on my phone, only to see an absolute frenzy of feverish discussion about a nuclear power plant in Ukraine.

Russian forces were fighting Ukrainian ones in and around the facility. Russians were shelling the area. And Twitter naturally feared the worst, namely that the plant would somehow explode, leading to an event 10x worse than Chernobyl.

To be sure, attacking a nuclear power plant, especially one that’s actively operating, is unprecedented and reprehensible. Could it lead to what the most dramatic of Twitter prognosticated? Let’s explore why the answer is no.

Built Different

In some senses, the events over the weekend were a great stress test. Not that I would hope anyone ever attacks or tries to take a nuclear power plant by military force ever again, but it offered the first example of this playing out in real time. And it made me cautiously more confident in nuclear power than not.

What happened?

- Russian and Ukrainian forces fought at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in Ukraine

- The Zaporizhzhia NPP is Europe’s biggest, with 6 reactors

- It supplies up to 20% of Ukraine’s electricity, giving it a lot of strategic import if you’re fighting a 20th century war, as Putin seems hell bent on doing.

- As part of the fighting, Russian forces shelled the plant itself

- A small fire broke out in the training center of the plant as a result

- The fire was subsequently put out without damage to infrastructure; radiation levels never increased materially

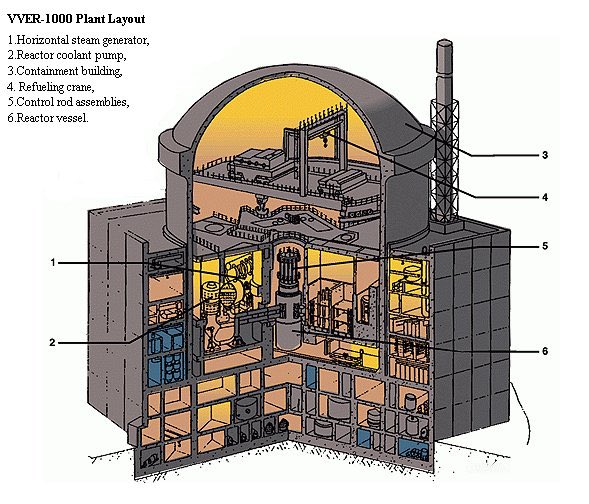

The Zaporizhzhia plant is a VVER-1000 plant. VVER refers to the plant type, a ‘water-water’ energetic reactor. Russian VVER plants have been around since before the 1970s; the 2x water reference refers to the plant being both water cooled and water moderated.

The 1000 plant type itself was operationalized in 1975, making it notably newer (not to mention different) in design than the reactors that were in use in Chernobyl and Fukushima.

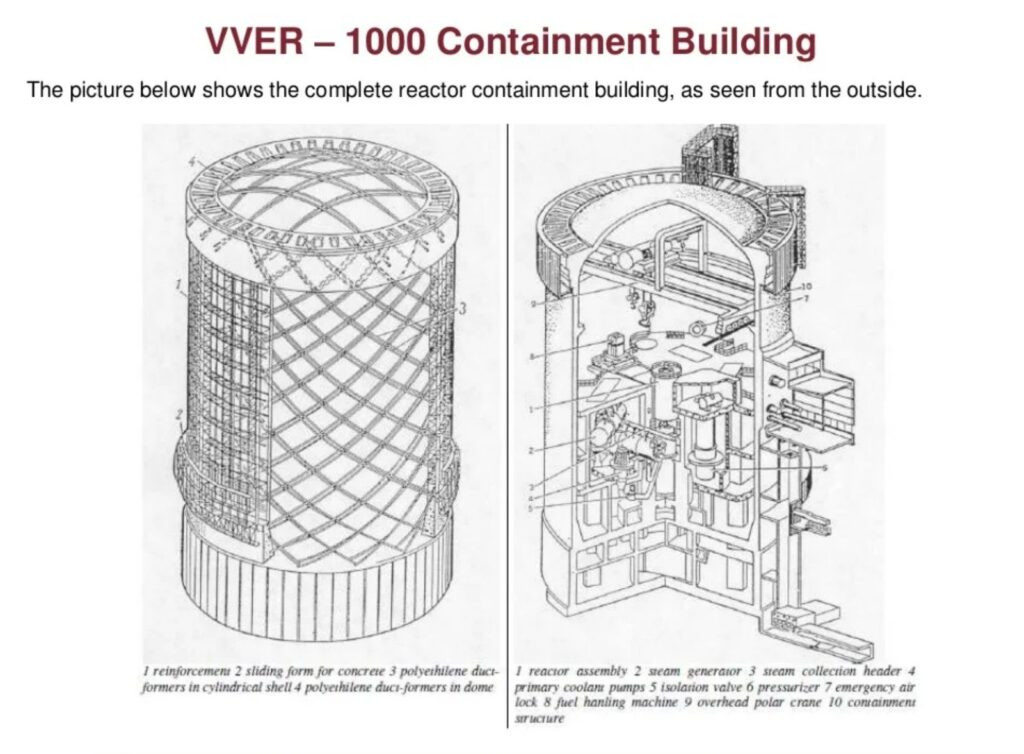

One big way that these reactors differ from those that spooked the world away from nuclear at Chernobyl? The reactors themselves – where radioactive material lives – are housed inside the extremely thick containment domes. These are made out of one of man’s miracle materials, concrete – and do exactly what it sounds like. They can withstand a missile strike, and in the extremely unlikely event of a meltdown, also help contain nuclear radiation.

REAL RISKS

Containment domes effectively render mute the headline concern we saw on Twitter, namely a scenario where a bomb or stray bullet itself could somehow ‘blow up’ the reactor. To do that, you’d basically need to get inside the containment dome itself and attack the nuclear reactor on purpose. Even then, a reactor is quite dissimilar to a nuclear weapon; it’s not designed with destruction in mind.

Still, there are a number of other valid concerns when there’s fighting at a NPP. Specifically around whether the fighting could disrupt the safe operation of the plant.

Under uncertain circumstances, like the ones witnessed Friday, it’s important that reactors at NPPs are ‘shut down’, meaning the reactivity of the materials within the reactor is reduced below a certain threshold.

At the time of the fighting at Zaporizhzhia, 3 of the 6 reactors at the plant were already non-operational. The rest were shut down as the fighting proceeded.

Shutting down reactors isn’t as simple as flipping a switch however. Even when ‘switched off’, the reactors continue to generate a lot of residual heat as nuclear material inside them continues to decay.

This heat importantly needs to be cooled; when cooling fails, you run the risk of a meltdown (i.e. to the ‘melt’ part of the word).

Normally, cooling is powered by electricity from the grid. When that power source fails or is off for whatever reason, there are robust back-up cooling systems.

When both fail is when you have a serious problem. E.g., at Fukushima, a tidal wave swamped backup generators, disabling all cooling there.

This speaks to what the real risk at modern NPPs is. It’s not that a missile strikes a reactor. It’s that warfare interferes with the teams that know how to safely run and shutdown reactors from being able to do their jobs. Or that something impairs electricity sources for cooling / back-up cooling systems. Or both.

As far as a stress test is concerned, this event showed how much thought goes into the ability of plant teams to safely operate even under extreme conditions. None of this is to detract from how heinous an act of war attacking an NPP or even just fighting in the vicinity of an NPP is. Still, suffice to say you don’t need to worry about a missile setting the equivalent of a nuclear weapon off on accident. Understanding whether events on the ground would stand in the way of proper plant operation is much more important.

MY TAKE

For a few more words on the matter? Despite the predictions of doom that flooded the feeds on Friday night, the pendulum that has swung decisively away from nuclear power for decades continues to inch slightly back in its favor. Perhaps because other people view what happened at Zaporizhzhia in the same way I do, namely as a source of even more confidence in NPP plant design and operation.

Whether or not people see Zaporizhzhia as a net positive or net neutral, against the backdrop of skyrocketing global energy prices, with oil at ~$130 a barrel and natural gas prices in Europe practically off the charts, a cadre of global icons ranging from Elon Musk to Marc Andreeson are in favor of bringing more nuclear power capacity online.

Of course, these people aren’t the decision makers. But there’s plenty of countries that are taking a second look at nuclear in light of everything going on. The green party in Belgium is notably backpedaling; previously they’d been staunchly in favor of shuttering remaining NPPs in Belgium by 2025. Now? They see the potential merits of leaving that power generating capacity online a while longer, if not forever.

In response, there’s plenty of environmentalists saying no, it’d be much better to develop more renewables. NPPs do take a lot of time to build and are quite expensive.

To this I say we need less “but” and “and”. Current projections forecast the U.S. will still be ~75% dependent on fossil fuels in 2050. The world needs to develop more of everything that’s low in emissions and meets key sustainability criteria. If not to combat climate change, then to make energy free and abundant.

Finally, returning to the question of why attack the plant… perhaps there’s an element of ‘three-dimensional’ chess Putin was trying to play here to try to spook the world away from nuclear power again. Which could help entrench global dependence on two key Russian exports – oil and natural gas – even further.

As with many things Putin wanted to accomplish, I think we can tally that as another ✔️ in the ‘L’ column.