02 November 2023 | Climate Tech

A carbon removal thought experiment

By

My last piece on this beat explored false binaries in carbon markets as well as the danger of false binaries in general.

To keep you on your toes, I am now starting this newsletter with a binary.

I know, I know. A month ago, I wrote:

If you ask me to pick a side between permanent carbon removal solutions and ‘less permanent’ ones, I respectfully decline to engage. I don’t consent to the binary, to begin with.

I’m not here to pick sides. I stand by what I said then. Nor am I here to carry on conversations with myself. But I am interested in presenting a thought experiment, even though it starts with a binary.

If you were a carbon removal buyer, would you prefer:

- 10,000 tonnes of carbon removal, ‘delivered’ in 10 years, that’s ‘permanent’ for 1,000 years

- 10,000 tonnes of carbon removal, ‘delivered’ today, that’s ‘only’ permanent for 25-50 years?

By permanence, I am referring to “…the predicted duration that carbon that has been removed will stay out of the atmosphere,” as I previously defined it.

Right now, major corporate buyers of carbon removal are primarily choosing option #1. As I wrote in the last permanence-focused newsletter:

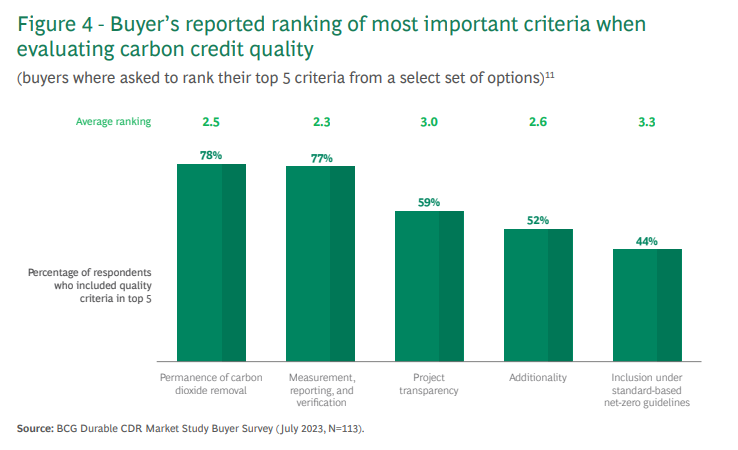

Increasingly, major buyers of carbon removal credits and investors in the industry side with Bill. Permanence is the most important criterion for many of them in evaluating their carbon removal purchases (as visualized below, per a recent BCG report).

It’s not my job to tell companies what to do with their cash (though if you want to consult me, I’m happy to do it). I support companies that are, absent regulatory pressure, taking voluntary measures to catalyze carbon removal. That’s laudable. They should choose whatever carbon removal they like.

I also understand why permanence as a goal is attractive to buyers. Corporations have to manage PR risk, lest they get mentioned in an article like the recent New Yorker exposé.

Plus, there are many reasons permanence is important beyond corporations trying to manage the risk of negative PR, which we’ll also explore.

But if you ask me where I land on the thought experiment we started with, I wouldn’t be as adamantly aligned with long-term permanence as many in the carbon removal industry currently are. Let me explain why.

Getting our priorities permanence straight

The first question I’d ask when we consider the question of permanence is why does 1,000-year permanence (or longer) matter? For any of our carbon removal efforts to matter, we collectively, as a global society, need to reach a net-zero economy much sooner than that.

Even if carbon removal scales to a 5-10 gigatonne industry, which would be an enormous feat, that would only reduce ~20% of annual global emissions at present. Until emissions are fundamentally much lower, carbon removal is far less necessary or valuable than emissions reductions.

That isn’t to say we shouldn’t develop highly permanent carbon removal solutions or carbon removal solutions in general. We should. We will need them down the line, whether to offset leftover emissions from the hardest-to-decarbonize use cases or to reduce atmospheric greenhouse gas emission concentrations, which won’t fall quickly even once emissions peak.

Nor am I saying short-term permanence is necessarily as good as long-term. I just think it has a role to play.

Why? Because the vintage and volume of carbon removal are essential factors, alongside permanence. All else equal, a tonne of carbon removed sooner rather than later is more valuable for a variety of reasons:

Global warming: CO2 lingers in the atmosphere for hundreds of years. The earlier CO2 is emitted, the more time it has to ‘do’ global warming. Conversely, the earlier CO2 is removed, the less global warming it can cause. Only removals that happen before peak warming can reduce peak warming. Further, if you’re concerned with climate tipping points, front-loading more removal helps.

‘Cover’ for decarbonization: The longer into the future we look, ideally, the lower the world’s annual emissions footprint will be. Granted, that may take another decade or two. Still, a tonne of carbon removed today should represent a larger % share of total global emissions than a tonne of carbon removed in 50 years will.

‘Cover’ for tech improvement: In 50 years, technologies manage CO2 should be more sophisticated. Someone recently reflected to me that excess CO2 in the atmosphere is just a resource we haven’t learned to harness yet. I think that’s a bit overly optimistic. Still, removing a tonne of carbon today, even if it’s only permanent for 50 years, provides ‘cover’ for the entire decarbonization complex to mature while mitigating warming in the short term.

To distill this down, in discussing these ideas with Colin Averill of Funga, he shared the following:

I love your thought experiment. This is the core of it. Three things are really key for carbon removal. Everyone wants large volumes, millennial scale permanence, and near-term delivery, or near-term ‘vintage’. Given the carbon removal tech that exists today, you can only have two of the three. Carbon markets are really focused on the first two and generally ignore the third. These things all trade off to some extent, but a 2030 carbon removal vintage is more valuable than a 2050 vintage.

I agree with Colin that we are perhaps undervaluing the third component, namely, when carbon is actually removed.

To approach what we’ve said so far somewhat differently, I’ll introduce a bit of an Aristotelian approach and take things to a logical extreme.

We have carbon removal technologies, like reforestation, that, while not highly permanent, can remove carbon today and aren’t drastically expensive.

Let’s imagine that by 2053 or 2073, we’ll have a) made significant decarbonization headway and b) more advanced engineering carbon removal solutions that work well and aren’t drastically expensive.

If that were true, should we so much about multi-century permanence?

If carbon removed today is re-released in 2053 or 2073, we should be able to deal with it more easily than today. If we still don’t have that capacity, or haven’t peaked emissions by then, we’ll have bigger problems to worry about.

I’m not the first person to think about these ideas and tradeoffs by any means. Favoring short-permanence carbon removal with an eye for storing it more permanently in the future is referred to by some people as horizontal stacking; it’s a known strategy.

Given that I’m far from the first to discuss this, let’s make sure to discuss counterarguments, too.

Counterarguments – the pragmatists path

Now that we’ve laid out some arguments to question the need for centuries-long permanence, let’s explore counterarguments (beyond corporations’ PR needs). I put the question to the Twitter, nay, X, hivemind this week and got many thoughtful responses. These include, but aren’t limited to:

Duration matching: Greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere stay there for more than 50-100 years. So, if companies want to use credits to “offset” their emissions, the permanence of their removal activities (‘assets’ they purchase) should match the duration of their emissions (‘their liabilities.’)

Durability correlation: Durability and permanence are not the same thing in my parlance. But they can be correlated. Durability refers to the risk of a release of carbon before the end of projected permanence. I.e., something happens and carbon is released in year two, not 20 or 200. More permanent stores of carbon are often more durable; injecting CO2 underground and / or mineralizing it is both a more permanent and more durable store.

Tech risk: While I hope our ability to manage carbon in general will improve, there’s no guarantee it will, or at least that it will significantly.

Ethics: Even if our carbon budget is fundamentally different by 2073 or 2123, “scheduling” major releases of previously sequestered carbon perpetuates the cycle of punting problems to future generations. While perhaps not an insurmountable technical challenge, it may strike you as an ethical one.

Lack of market sophistication: Markets for carbon removal credits ‘feel’ like they ‘want’ to approximate commodity markets. We don’t yet have the level of sophistication to offer countless different carbon products across varying degrees of permanence. Standardization helps, and right now, standards are converging toward longer permanence.

The biggest risks, i.e., the arguments I appreciate most, are the first two. The worst thing that could happen with this newsletter is that corporations with a significant emissions footprint pick it up, argue they’re doing the right thing by prioritizing volume and vintage over permanent sequestration, and then continue business as usual, emitting long-lived CO2 into the atmosphere while “offsetting” it with carbon credits that feature a short-lived permanence.

Further, I do think if you couple longer permanence with greater durability, that’s a solid argument for prioritizing sequestration technologies like mineralization and underground injection.

I’m also sensitive to the fact that there is a logical extreme at the other end of the spectrum than the one we laid out earlier. Carbon removal with, say, one year of permanence isn’t very valuable.

Carbon removal with ten-year permanence probably isn’t particularly valuable, either. I don’t know where the threshold of permanence starts to approach ‘valuableness,’ as I don’t know when global emissions will peak. Right now, they’re still rising. Suffice it to say it is definitely fair to be more skeptical of carbon removal the more short-lived its promised permanence.

The net-net

To again reiterate my distaste for binaries, as well as to state the obvious to an extent, we need both short and long-duration carbon removal and sequestration. The long-duration side needs catalysis now so it can scale to help reduce emissions permanently from hard-to-abate sectors in the future. And the short-duration side is essential to combat global warming now and bend the emissions curve (as well as for all kinds of other nature-based and ecosystem co-benefits).

All of today’s discussion is my attempt to attune us to the fact that we may be underindexing on the timing of carbon removal deliveries. It’s great when companies like Amazon and Microsoft pre-pay (to the tune of 7-8 figures) for future carbon removal deliveries. And companies, philanthropists, and other stakeholders alike should step up and fund less sexy, less permanent carbon removal that can be delivered today. Even amidst the PR fallout that nature-based solutions are reckoning with.

As the U.S. government concretizes its support of direct air capture, the largest existing demonstration of which only captures 4,000 tonnes of CO2 annually right now, other organizations will have to stand up for the less permanent approaches. They’re just as important an arrow in the quiver of decarbonization and, ultimately, reversing atmospheric CO2 concentration.