07 January 2023 | Healthcare

Fast-Track Approval: Balancing Speed and Safety in Drug Approvals

By workweek

The FDA’s Fast Track approval program, designed to speed drug development for life-threatening conditions, has faced increased scrutiny over the years. I’ve mainly used Biogen’s controversial Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm to shed light on the accelerated approval problems. However, the problems run deeper than Aduhelm.

In this article, I’ll highlight the FDA’s Fast Track approval program, dive into its fundamental problems, and discuss solutions to improve the much-needed program.

The Deets

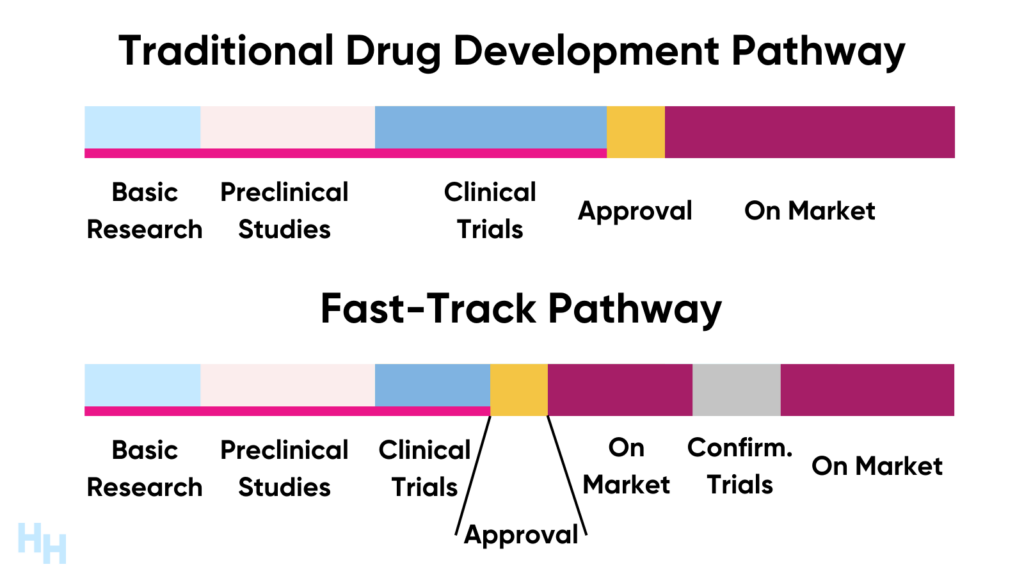

The FDA created the Fast Track program in 1992 to speed drug development to treat life-threatening diseases like HIV and cancer. The traditional drug pathway may take around 15 years to bring a drug from research and development to market, no matter how beneficial the drug may be as evidenced in clinical trials. The traditional drug pathway may therefore do a disservice to patients with life-threatening conditions if a promising treatment is stuck in clinical trials for years.

Fast Track approval speeds up the traditional drug pathway timeline, but drugs still go through all the same steps and are held to the same safety standards. The difference, however, is researchers can use surrogate or intermediate endpoints as a means to assess the drug’s clinical efficacy. For example, when antiretroviral therapies were in development to treat HIV, researchers used plasma HIV-RNA levels (low vs high) as a surrogate to measure the clinical efficacy of the therapies instead of waiting years to evaluate the clinical effects. In fact, expedited drug development to treat HIV was the impetus to the Fast Track program.

So Fast Track drugs can go to market without ever showing actual clinical benefit?

Yes and no.

The FDA requires sponsors of drugs with Fast Track approval to follow up on confirmatory trials after the drug is on market. For example, the drugmakers of Fast Track antiretroviral therapies would have needed to show a significant survival benefit compared to placebo (or standard of care) after the FDA approved the drug for market. If the confirmatory trial were negative, the drugmaker would have had to withdraw the drug from market.

This is where things get shaky.

Up until a couple of weeks ago, the FDA’s power to truly withdraw unproven drugs from market was futile. Drugmakers like Amylyx would make voluntary pledges to withdraw their drug from market if confirmatory trials couldn’t support the drug’s efficacy.

But can you really trust a multi-billion dollar drug company to “voluntarily” pledge to withdraw their drug after it has already made millions by its early market exposure?

My gut says no.

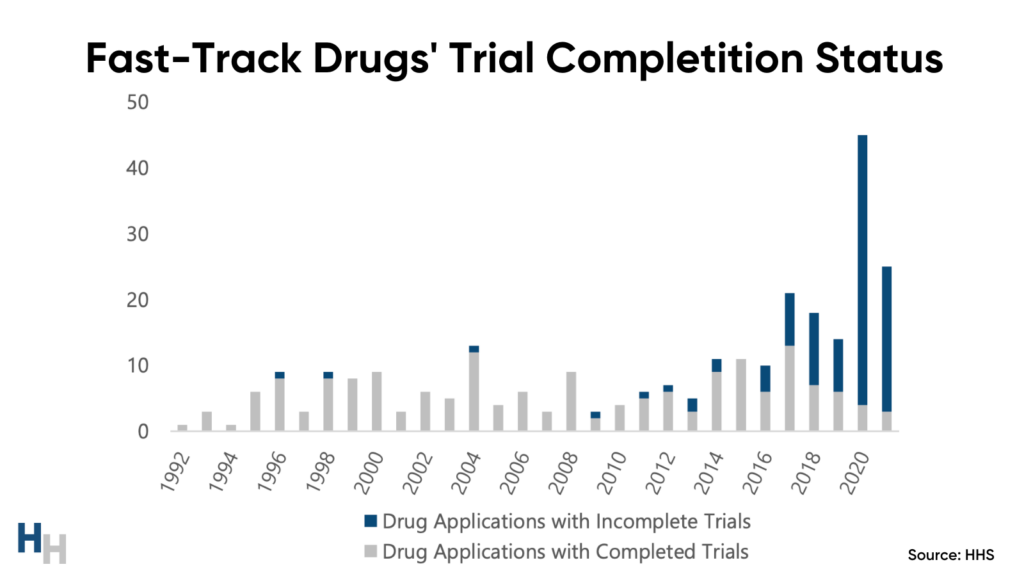

So far, the FDA has withdrawn 35 (13%) of the 280 drugs that have gone through the Fast Track pathway. While you may think the confirmatory trial and withdrawal system is working—it’s not. One-third of Fast Track-approved drugs on market still lack their “required” confirmatory trials.

The Problems: Confirmatory Trials and Withdrawal

Sponsors of one-third of all drugs granted accelerated approval still need to complete their confirmatory trials. Said another way, drugs that may offer no clinical benefit are on the market, being used by patients and paid for by insurers.

Makena’s Story

The FDA granted Makena—an injectable drug for the prevention of preterm birth—accelerated approval in 2011, despite advisors not agreeing on the strength of the drug’s efficacy from clinical trials. Advisors suggested Makena’s sponsor perform an interim trial to gather more evidence of the drug’s benefits. Sounds reasonable! But, the FDA decided that delaying this drug’s approval any longer would harm patients, given the prevalence of preterm birth and lack of medications to prevent preterm birth. So, the FDA approved Makena and required a confirmatory trial by 2016.

Makena’s sponsors completed the confirmatory trial in 2019, three years after the predetermined due date. The trial data wasn’t promising. An FDA advisory panel reviewed the data and determined unanimously that the evidence did not support the drug’s clinical benefit, requesting the drugmaker to withdraw Makena from market.

The drugmaker refused to withdraw it.

The FDA has been fighting for three years to remove Makena from market. In October 2022, an FDA advisory panel voted 14-1 to have Makena’s drugmaker remove it from market. The drugmaker continues to argue the FDA’s decision.

So, going back to my earlier question: can you really trust a multi-billion dollar drug company to “voluntarily” pledge to withdraw its drug after its already made millions by its early market exposure?

No!

Makena is just one example of a drugmaker refusing to pull its drug from market despite insufficient evidence of its efficacy.

Why are Confirmatory Trials and Withdrawal so Cumbersome?

The systems in place for Fast Track make confirmatory trials so difficult to perform and withdrawing unproven drugs so cumbersome.

Confirmatory trials are difficult to run because of confounding variables that may influence the drug’s benefits. That is, the standard of care for certain conditions may improve health outcomes over the years, thereby making it seem like the Fast Track drug is providing the benefit.

Additionally, confirmatory trials usually happen after the drug reaches market, making trial enrollment difficult. If a patient has access to a drug that may improve their condition, why would they enroll themselves in a clinical trial and risk being placed in the placebo group?

Lastly, the withdrawal process for drugs with insufficient evidence in confirmatory trials is anything but accelerated. The withdrawal process can take months to years since it’s up to the drug’s sponsor to voluntarily withdraw the drug from market. Here are the steps:

- FDA details the reasons for withdrawal

- Withdrawal hearing if requested by the sponsor

- Presentation of evidence and questioning by FDA and the sponsor

- Decision by the FDA Commissioner

- The sponsor may then petition a court to review the Commissioner’s decision and request an order to stay the action pending review

The Impact on Patients and Insurers

The mishaps with confirmatory trials and subsequent withdrawal process impact patients and insurers.

Patients may take on unnecessary health risks by remaining on medication with questionable—or unconfirmed—benefits. For example, some of Makena’s risks are an increased risk of cancer in exposed offspring, including pediatric brain cancer.

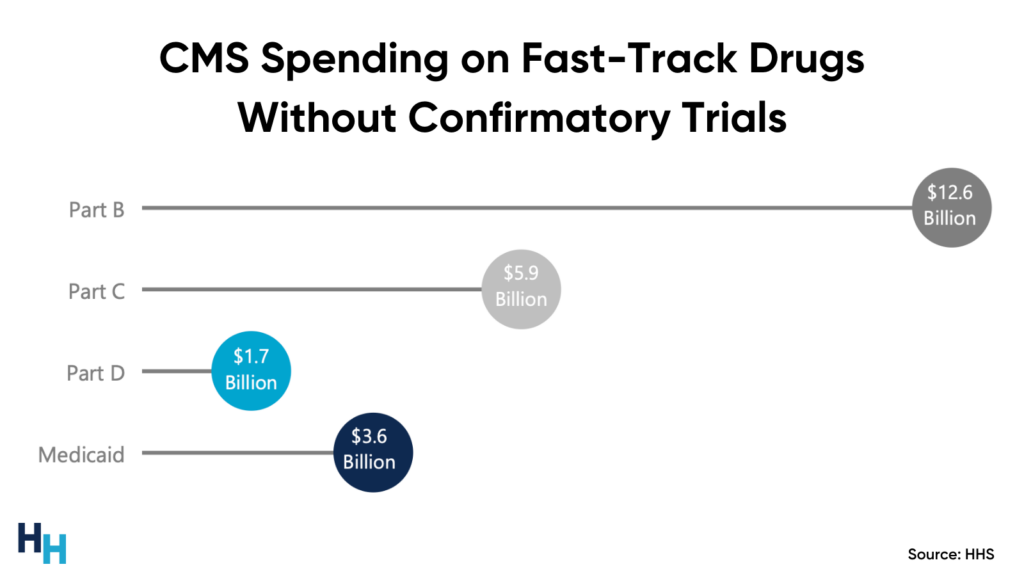

Insurers, especially CMS, may end up paying an exuberant amount of money to cover a drug that lacks any clinical benefit. In fact, CMS paid at least $18 billion (2018-2021) for Fast Track drugs that have yet to complete their confirmatory trials by their predetermined date. For Makena, CMS has paid over $700 million.

A more poignant example is when CMS announced in November 2021 a 15% increase (from $148.50 to $170.10) in Part B premiums to proactively set aside money to pay for Fast Track-approved Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm. This was the largest Medicare Part B premium increase in history. CMS essentially had to pay more money to cover a controversial drug and patients had to pay more in premiums.

Dash’s Dissection

The FDA’s Fast Track program must balance speed and confidence: speed to get promising, life-saving drugs to market as soon as possible and confidence that these drugs are indeed life-saving. To achieve confidence, the FDA must make the confirmatory trials requirement more robust and accelerate the withdrawal process for drugs with insufficient evidence of clinical benefit.

Recently passed legislation addresses the confirmatory trial and withdrawal problems. Here are some updated regulations:

- The FDA is required to specify the conditions for required confirmatory trials for Fast Track drugs. The FDA may now also require confirmatory trials to be underway prior to approval.

- The withdrawal process is updated to accelerate a drug’s removal from market.

- Sponsors must report on confirmatory trial progress every 180 days after approval until any required confirmatory trials are completed.

- Failure to conduct required confirmatory trials “with due diligence and failure to submit the required reports” can result in criminal prosecution.

While these updated regulations are a start, here are some other solutions to consider:

- Require at least two later-stage clinical trials to support the drug’s efficacy prior to approval.

- Set an expiration date on approval, which would incentivize sponsors to complete confirmatory trials to convince the FDA to keep the drug approved.

Keep in mind that as requirements placed on the Fast Track pathway become more stringent, the pathway will begin to mirror the traditional drug pathway, which would defeat the purpose of the Fast Track program.

Lastly, the FDA just granted Eisai and Biogen’s Alzheimer drug Leqembi (lecanemab) Fast Track approval. The FDA based its approval on Phase III clinical trial demonstrating lecanemab at the highest dose slowed clinical decline by 27% compared to a placebo over an 18-month period. Eisai and Biogen have already run the confirmatory trial needed to for full clearance of lecanemab, which will be announced in the upcoming months.

In summary, the FDA’s Fast Track program is aimed at speeding life-saving drugs to market, with the confidence that these drugs are indeed effective. The FDA requires drug sponsors to perform confirmatory trials after the drug’s Fast Track approval to confirm the drug’s clinical benefits. If confirmatory trials do not support the drug’s efficacy, the drugmaker is to remove the drug from market. The main problems with Fast Track stem from drug sponsors not performing their confirmatory trials and refusing to withdraw drugs lacking evidence of clinical benefit. Recently approved legislation addresses these problems to promote the speed and confidence the Fast Track approval needs.

If you enjoyed this deep dive, share it with colleagues. Sign up for the Healthcare Huddle newsletter here.