Every year, the National Small Business Association (NSBA) conducts a survey of small business owners. In this year’s survey, more than one-third of small business owners reported not being able to secure sufficient financing for their business, which was the highest that percentage has been since the start of the Great Recession in 2008. Consequently, the number of small business owners who said they were unable to grow or expand their business operations due to a lack of capital was at its highest point since the NSBA started doing the survey in 2007.

Given that small businesses account for 99.9% of all U.S. companies and nearly half of private-sector employment, that’s … not ideal. Nor is it particularly unusual. Inflation and concerns about a possible recession have definitely been recent headwinds in the small business lending space, but if you study the industry closely, you’ll see that small businesses, relative to other customer segments in financial services, are habitually underserved.

Why?

Well, you’ll want to make sure you’re sitting down for this definitely-revalatory-and-not-at-all-obvious insight – small business lending is really freaking hard.

OK, OK, I know that wasn’t some profound revelation. I think everyone knows that small business lending is difficult.

However, what I think folks may not fully appreciate is exactly why it’s so difficult.

And that’s important. We can’t fix the problem of small business owners not having sufficient access to capital unless we can first understand the problem.

A Unique Manufacturing and Distribution Challenge

The central challenge with small business lending is that it’s trapped between two different worlds.

One world – commercial lending – is defined by size. Each loan is massive (millions or hundreds of millions of dollars), which incentivizes lenders to invest a lot of time to acquire customers (there aren’t that many of these opportunities out there) and to underwrite them very carefully (you’re optimizing for a default rate that is measured in basis points). As such, commercial lending is largely a relationship business – humans are involved in pretty much every step in both the manufacturing and distribution processes because, with loans of this size, lenders can’t afford for them not to be.

The other world – consumer lending – is defined by scale. Each loan is small (tens, hundreds, or thousands of dollars), which doesn’t allow for the same bespoke manufacturing and distribution process that lenders use for large commercial loans. Consumer lending is a game of efficiency. Acquisition is a combination of brand building and targeted outreach. Loan underwriting and servicing are all about automation and self-service. Lenders go to extraordinary lengths to keep humans out of the manufacturing and distribution processes because their value add just isn’t worth the incremental cost.

It’s a bit like the difference between painting a Toyota Sienna and painting a Rolls-Royce Wraith. The Toyota is going through a fully automated factory, where robots are painting each car in about 15 minutes. The Rolls-Royce is custom painted, with the color selected from 44,000+ different options (or having an entirely new color made from scratch), and if you want to add a pinstripe, you’ll need to get Mark Court, the only one of Rolls-Royce’s employees who is allowed to paint pinstripes, to do it by hand, a process that takes three hours per vehicle.

Small business lending isn’t a perfect fit in either world.

The bespoke, highly manual acquisition, underwriting, and servicing processes from commercial lending just aren’t economical for a $50,000 small business loan. Someone buying a Toyota Sienna can’t afford to have Mark Court paint a pinstripe down the side.

The scalable, highly automated model that we’ve built for consumer lending is a better fit, but it’s far from perfect. There are four primary reasons for this.

#1: Diversity

Strictly from a risk perspective, consumers are a relatively homogenous population. Roughly speaking, we all live for the same amount of time, want the same things, and behave in the same ways.

This makes us easy to model. If you give a lender someone’s FICO Score, income, and recent history of derogatory events (bankruptcies, liens, etc.), they can predict your likelihood to default on a loan with a great degree of accuracy, and that same model can do the same thing for your neighbor down the street and for your childhood friend who lives 2,100 miles away.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Small businesses are much more diverse.

The industry that a small business is in matters a ton. Dermatology providers are very different from HVAC installers, which are very different from biotech startups. Trying to evaluate businesses across industries is basically impossible because a “good” dermatology provider is going to look very different, in terms of margin structure and operating costs, than a “good” HVAC installer or a “good” biotech startup.

Geography also matters a lot. Is the city that the business is in growing or shrinking? Is the state that the business is in tax-friendly? Is the region of the country that the business is in likely to experience natural disasters?

And, of course, you also have to worry about the intersection of these different factors. Seasonality – the fluctuations of a business’s performance over the course of the year – matters enormously. An ice cream shop in Maine is going to be a very different proposition than an ice cream shop in Florida.

#2: Data Coverage

We take for granted how good the data coverage in consumer lending is. Love them or hate them, the three consumer credit bureaus provide incredible coverage.

If you were to send 100 random adult consumers to any one of the major bureaus, it’s likely that they’d be able to supply reasonably deep and comprehensive data on at least 80 of them.

If you were to send 100 random small businesses to all of the major business credit bureaus, you’d be incredibly lucky to get good data back on as many as 40 of them.

This isn’t a criticism of the business credit bureaus (Dun & Bradstreet, Experian, and Equifax) so much as an acknowledgment of just how hard their job is. Many small business lenders don’t report repayment data to the bureaus (unlike lenders on the consumer side), and many small business owners get credit for their businesses using their consumer credit histories.

Additionally, small businesses are inherently more dynamic than consumers.

Most consumers don’t change their names or move locations or pivot into completely different industries nearly as often as small businesses do. And, not to be morbid, but in any given year, only 1-2% of consumers die, compared to roughly 10-15% of small businesses.

Put simply, it’s much harder to assemble and maintain deep, comprehensive data profiles on small businesses than on consumers.

#3: Verification

It’s also more difficult to understand small businesses than it is consumers.

Verifying a consumer’s identity is fairly straightforward. You have a data profile, and you attempt to match the person you are interacting with against that profile. We aren’t perfect at this exercise (much to the relief of fraudsters), but we’re reasonably good at it.

Verifying a small business identity is much trickier. Companies are human constructs. As such, they are rarely intuitive and often quite complex. A single business can legitimately have multiple owners, addresses, and subsidiaries. Understanding and validating those variables and the relationships between them is challenging. How, for example, should you think about an accounting firm with two owners who each own 50% of the business but who have personal FICO scores that are 230 points apart from each other?

#4: Information Asymmetry

Information asymmetry – the difference between what the two parties in a transaction know – is a fundamental challenge in all industries, and an especially well-known one in lending, where a borrower who knows something that the lender doesn’t know (I’m about to get laid off from my job and I need liquidity) can render even the most careful underwriting process useless.

The problems posed by information asymmetry are magnified in small business lending because – and it’s worth emphasizing this point strongly – starting and operating a small business is an inherently irrational thing to do.

Most small businesses fail. And those that succeed often do so despite the predictions of smart, qualified outside observers.

I’m currently in the middle of Walter Isaacson’s biography of Elon Musk, and it’s striking how many successful investors and Silicon Valley luminaries were absolutely convinced that SpaceX and Tesla would fail (Sequoia’s Mike Moritz passed on Tesla because he was sure that competing with Toyota and the other legacy auto manufacturers was “mission impossible”).

In small business lending, the information asymmetry problem can cut deeply in both directions.

For the lender, it’s always likely that the small business owner knows something about the viability of her business and the competitive environment in which it operates that would make lending to her unacceptably risky, like, for example, if a new pizza restaurant is about to open across the street from hers and siphon away 40% of her business.

And for the small business owner, it’s nearly impossible for any lender to see her business with the same clarity with which she sees it. This isn’t surprising. The lenders aren’t living in the business, day in and day out. They’re not talking to customers or suppliers. They’re not executing marketing campaigns or restocking inventory. So it’s not surprising that lenders don’t understand small businesses as well as their owners do, but it can be quite frustrating for those owners when they see opportunities to grow their businesses and lenders won’t give them the capital they need to seize those opportunities.

Small Banks, Dominating by Default

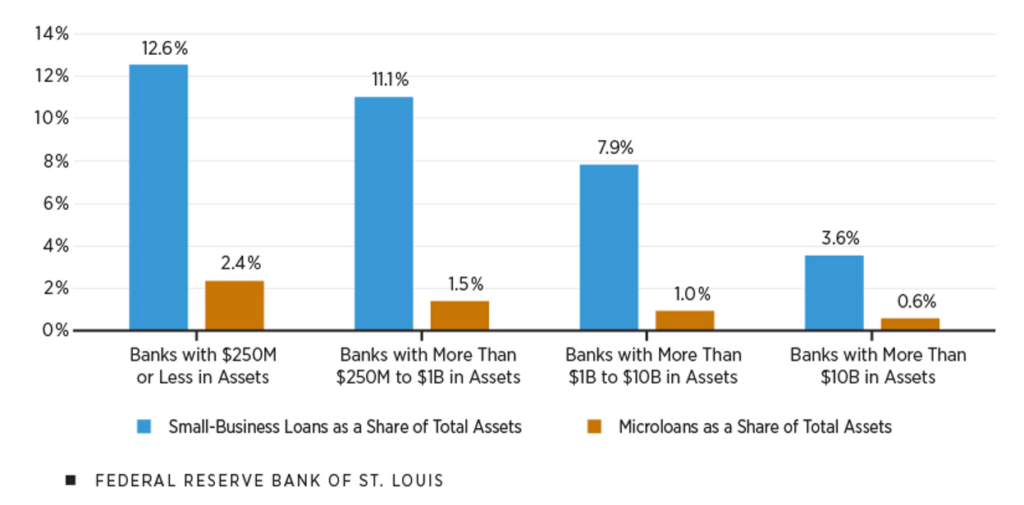

Given these challenges, it’s perhaps not surprising that small banks tend to dominate the small business lending ecosystem.

According to an analysis from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, small business loans (loans under $1 million) and business microloans (loans under $100,000) made up a significantly higher share of community banks’ total assets than they did for regional, super regional, and national banks.

This is less the result of an intentional strategy on the part of community banks and more the result of them taking whatever they can find after the bigger banks – which have the resources necessary to build scalable consumer lending businesses and to pluck the juiciest fruit from the commercial lending tree – have taken their share.

The bigger banks simply aren’t interested in small business lending.

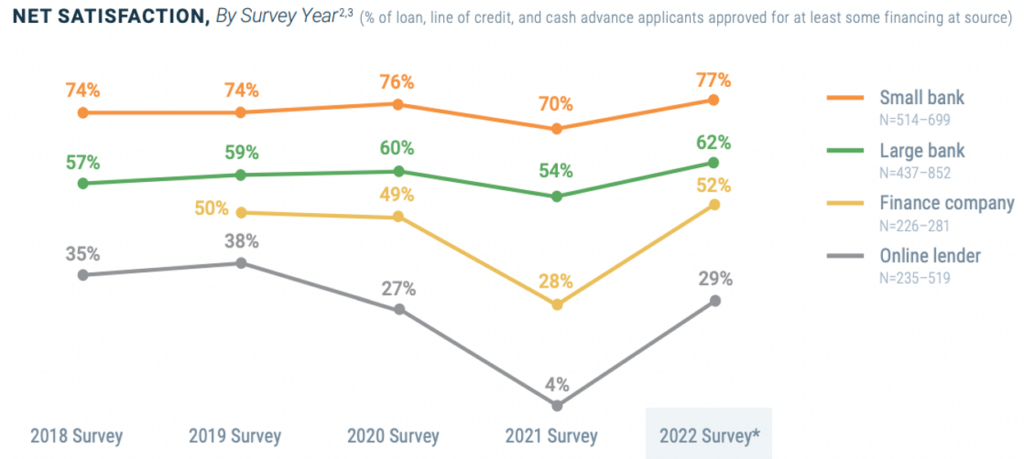

And small business owners aren’t necessarily complaining about it!

According to research from the Federal Reserve, small banks have consistently beat out big banks, online lenders, and specialty finance companies when it comes to customer satisfaction in small business lending:

Why are small business owners so satisfied with small banks?

Well, it’s because small banks, which make most of their money doing larger commercial loans, tend to use the same commercial lending process for their small business customers as well.

In other words, they’re giving them the Rolls-Royce treatment, even though the small business owners are only buying Toyotas.

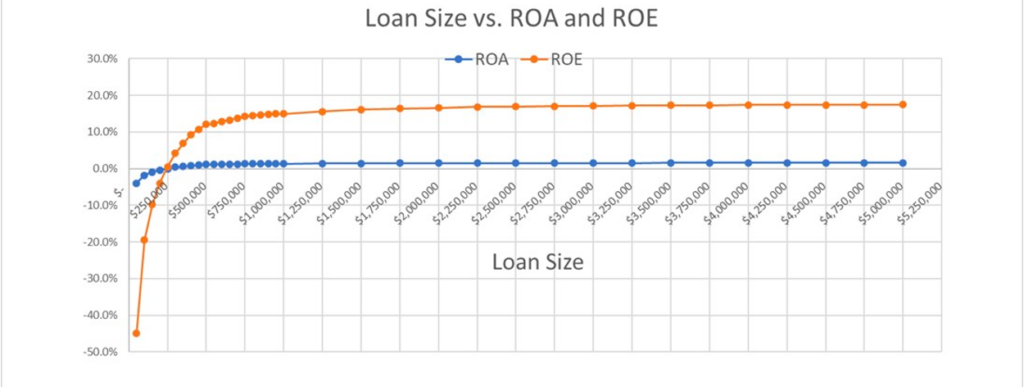

This begs a follow-up question – how are small banks able to profitably apply the commercial lending model to small businesses? How are these banks able to stay in business themselves?

First of all, many of them aren’t. Community banks have been disappearing at an accelerating rate over the last couple of decades as economic and competitive realities have incentivized more mergers and acquisitions.

Indeed, according to an analysis from SouthState Correspondent Division, the average community bank doesn’t break even on a commercial real estate loan until the loan size reaches $250,000.

However, to the extent that small banks have figured out how to make small business lending work, they’ve only managed to do it on a small scale.

In small business lending, specialization is enormously valuable. If you can specialize in a particular industry and/or geography, you can remove a lot of the variability that makes underwriting small businesses so tricky. And if you can approve a high number of applicants from that industry or geography, you can develop a reputation that will drive lower-cost customer acquisition and positive selection, which, in turn, drives safer risk decisions and the ability to approve more applicants.

It can be an effective flywheel, but it depends entirely on specialization and operating on a small scale.

This is the model that we have historically had in the U.S., and it has worked reasonably well, though clearly not well enough for the more than one-third of small business owners who told the NSBA that they could not secure the financing they need for their businesses this year.

The billion-dollar question is, can we do better? Can we knock down the costs of safely lending money to small businesses so that small business loans can become more accessible?

Fintech & First Principles

This question reminds me of a similar one from the Elon Musk biography – how much money does it cost to shoot a rocket into space?

When Musk first started SpaceX, his plan was to buy repurposed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) from private sellers in Russia and use them as rocket boosters. When he was told that the ICBMs would cost $21 million each (rather than the original price of $7 million each), he got so mad that he sat down and tried to figure out, from first principles, how much a rocket would actually cost to build from scratch:

Ever since he flew back from Russia and calculated the costs of building his own rockets, Musk had deployed what he called the “idiot index.” That was the ratio of the total cost of a component to the cost of its raw materials. Something with a high idiot index—say, a component that cost $1,000 when the aluminum that composed it cost only $100—was likely to have a design that was too complex or a manufacturing process that was too inefficient.

What he found, after calculating the cost of carbon fiber, metal, fuel, and other materials, was that the finished rocket he tried to purchase from the Russians cost 50x more than the inputs.

So, he went about building his own, with a maniacal focus on acquiring or manufacturing individual components at the lowest possible price (one example – the latches used by NASA in the Space Station cost $1,500 each, but a SpaceX engineer was able to modify a latch used in a bathroom stall and create a locking mechanism that cost $30).

Today, more than 70% of SpaceX’s parts are made internally, and the company can send cargo into orbit at 1/10th the cost of its competitors.

Like rockets, traditional small business lending has a high idiot index. Many of the costs are due to ill-fitting processes, ported over, without much thought, from the worlds of commercial and consumer lending.

These costs can be reduced down to four categories:

- Acquisition – the cost to market to small businesses and convince them to apply for a loan.

- Underwriting & Servicing – the operational costs to evaluate a small business applicant and, if they are approved, to service their loan.

- Losses – the cost of absorbing credit risk and fraud losses.

- Capital – the cost to acquire the capital to fund the loans.

Two things are important about these cost categories.

First, they are interrelated. The better your underwriting and servicing processes are, the lower your losses are likely to be. The lower your losses are, the lower your cost of capital (if raised from external investors) is likely to be. And so on.

Second, fintech innovation, focused on first principles, can meaningfully lower these costs.

How do I know?

Because we’ve already seen it!

Specifically, we’ve seen two recent waves of innovation in small business lending that have helped to drive down costs.

Wave #1 – Online Lenders (2009 – 2013)

The big innovation introduced by online lenders in the late 2000s and early 2010s was the redesign of the small business loan underwriting process.

These providers looked at the 25-30 steps in the traditional small business underwriting process and asked a couple of important questions:

- Which of these steps meaningfully contribute to our ability to understand a business’s risks, and which may be legacy steps that we’ve simply ported over from traditional commercial lending workflows?

- For the steps that do positively contribute to our risk evaluation, how can we automate or streamline them in order to reduce our costs? For example, we know that a site visit is important for brick-and-mortar businesses, but can we do a digital site visit (using Google Maps street view) rather than sending someone to the site to physically to verify it?

- How can we sequence the newly streamlined steps in our process in order to do as many of the inexpensive steps upfront, thus reducing the number of applicants that make it to the more expensive steps later in the workflow?

By asking these questions and redesigning the underwriting process around the answers, online lenders like OnDeck and Kabbage created a vastly more efficient template for originating small business loans.

Wave #2 – Closed-Loop Platforms (2011 – 2016)

By adding lending products into their existing merchant product suites, large merchant enablement platforms like Amazon and Square provided early proof points for how embedded finance can fundamentally transform cost structures in small business lending.

The big one is acquisition. These closed-loop platforms already had massive customer bases. They didn’t add in lending to drive new growth but rather to improve retention and engagement with their core services. As a result, they knocked perhaps the single most expensive line item for small business lending down to, effectively, $0.

The closed-loop platforms also brought more efficiency to the loan underwriting process by leveraging their control over their own proprietary data to improve their risk models. Because these platforms are where small business owners conduct business, the lending arms of these platforms were able to gain privileged, real-time insight into the financial condition of their prospective borrowers. This insight drove down underwriting costs and credit risk losses and made it possible for the platforms to proactively cross-sell loans based on the anticipated trajectories of the businesses.

Wave #3 – ? (2016 – Today)

Obviously, innovation in small business lending didn’t stop when Shopify launched Shopify Capital in 2016. However, I would argue that much of what we’ve seen since then has been more of an extension of these first two waves than the beginning of something entirely new.

Wayflyer, Ampla, and Clearco are all online lenders in the model of an OnDeck or Kabbage, but with a sharper focus on specific market segments (particularly e-commerce, where the available data feeds can provide lenders with a startlingly similar picture to what business owners see on a day-to-day basis).

Toast, Mindbody, and Procore are all commerce enablement platforms for small business owners, which have extended into lending, much like Amazon and Square. The difference is that these newer platforms are focused on specific verticals like restaurants, spas, and construction contractors.

That’s all good progress, but does it represent the absolute outside limit of where first principles thinking in small business lending can take us?

Or is there further to go?

Where Can We Push the Limits?

I think we can go further.

Despite the progress that we’ve made in fintech to streamline the small business lending process and drive down costs, there are still far too many areas within the process where manual interventions and human judgment are required.

I want to highlight three such areas and discuss how we might be able to drive to greater levels of efficiency.

#1: Customer Acquisition

There is, perhaps, no bigger difference in costs in small business lending than the one between direct marketing (direct mail, digital advertising, etc.) and embedded distribution (cross-selling to existing customers).

Unfortunately, the benefits, so far, of embedded small business lending have accrued only to the owners of large, established small business platforms that have been willing to operate their own proprietary lending arms (Amazon, Square, Shopify, etc.)

This seems likely to change within the next 5-10 years.

The number of software platforms out there that could act as distribution channels for small business loans dwarf the number of such platforms that would want to do all the work necessary to set up their own in-house lending businesses.

Thus, partnerships!

We’re already seeing the emergence of fintech companies focused on providing small business loans through embedded partnerships (such as Kanmon). My guess is that we will soon see fintech companies choosing to act strictly as intermediaries, connecting front-end platforms looking to embed small business loans for their customers with back-end banks and non-bank lenders looking for efficient growth channels.

#2: Cost of Capital

As I wrote about recently, it has become much easier over the last few decades for non-bank lenders to arrange debt capital facilities to fund their lending programs.

When OnDeck started in 2006, small business loans originated by non-bank lenders were not seen as a viable asset class in which to invest, which made access to capital for non-bank small business lenders like OnDeck both difficult to come by and expensive.

Today, non-bank small business lenders have more and better options.

That said, there is still a large amount of friction and overhead in the process that needs to be stripped out. Non-bank lenders arranging their first debt capital facilities have a lot of hoops to jump through (explaining their operational processes, creating data tooms, etc.), and once the facilities are in place, the management and governance of them are typically done using cumbersome thousand-page loan agreements that are impossible for normal people (and expensive for lawyers) to parse.

The good news is that much of that busy work (and the costs associated with it) is slowly trending towards zero thanks to the efforts of fintech companies like Sivo, which has built a debt-capital-as-a-service offering for very early-stage fintech companies (Sivo and Ntropy recently partnered to further accelerate this shift).

#3: Underwriting

Small business loan underwriting has changed significantly in the last 15 years, which has been both a positive and a negative for lenders.

On the positive side, we have a lot more data available to help us make lending decisions than we used to. In addition to traditional business credit data, we now have access (with customers’ permission) to business bank account data (from providers like Plaid and MX), sales and performance data for e-commerce companies (from providers like Rutter), and accounting data (from providers like Codat and Railz).

This is really cool! This data is extremely useful in filling in some of the gaps in business credit data and giving lenders more context on the businesses they are evaluating.

However, all this data also creates a problem – it’s messy and difficult to deal with.

Take accounting data as an example. On the surface, this data is extraordinarily useful (it’s a comprehensive picture of a company’s finances), and it is becoming much easier to get access to in a programmatic way (thanks to the integrations that providers like Codat and Railz have built into popular SMB accounting software products like Xero).

However, if you look a little deeper, you will realize that accounting data has some significant challenges. It’s often out-of-date by as much as 6-12 months because small business owners don’t have the time or resources to keep it up to date. It’s not standardized because every small business owner does their books in a slightly different way and outputs the data in a slightly different format. And sometimes, it’s just flat-out wrong.

Small business lenders want to use accounting data to make better lending decisions, but wise lenders do not simply integrate with an accounting data API and trust that the data provided by that API is going to be exactly what they need.

Indeed, in researching this essay, I spoke with multiple fintech lenders focused on the small business space who told me that a majority of their underwriters’ time (as much as 80%) is spent aggregating, transforming, and formatting all of this data to get it into a structure that actually allows them to make an underwriting decision.

That’s … extremely inefficient, and inefficiency is what wrecks margins in small business lending.

However, traditionally, we haven’t had any other choice. We needed humans to do this work.

Then came generative AI.

Generative AI, as I wrote about recently, is a new field of artificial intelligence that is particularly good at analyzing and retrieving information from large datasets that are very diverse in format, source, and structure.

Prior to generative AI, you needed a model trained on very specific information to complete one task. As soon as there was a deviation from what the model had seen, it would tend to break, which made the last mile incredibly hard and expensive. Maintaining and updating many in-house models and continuously adding more data for incremental returns did not work very well for business lending and many back-office tasks. It just made more sense to throw humans – with our generalized reasoning and problem-solving skills – at it instead.

State-of-the-art generative AI models are proving effective at replicating these generalized reasoning and problem-solving skills, which means that these models have the potential to remove the last mile of low-level human reasoning and judgment from the back-office processes that govern small business loan underwriting today.

Imagine – instead of paying humans to cut and paste data from PDFs, manually categorize transactions, parse business tax returns, review a small business’s website, or validate that a Google Maps street view image matches the description of a business on an application, what if we could assign a cheerful and tireless generative AI model to the task and let it do the work faster and at a fraction of the cost?

Separating Rules From Recommendations

According to Elon Musk, “The only rules are the ones dictated by the laws of physics. Everything else is a recommendation.”

In the traditional world of small business lending, it was almost impossible to distinguish between rules and recommendations. Big banks didn’t have the incentive to push the limits using first principles reasoning, and smaller banks didn’t have the resources.

Then came fintech, and it suddenly became crystal clear that the recommendations that the industry had been following and that small business owners had been suffering under weren’t really based on anything.

It turns out that there’s a lot we can do to automate the process, at scale, to reduce costs and make small business lending a more widely profitable venture.

We may, one day, run up against some hard and fast rules that we can’t push beyond, but it hasn’t happened yet.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Ntropy.

Ntropy builds language models to understand financial data at scale. They take raw financial data in any format, any data source and any geography and provide a clean, standardized and enriched output to power fast and accurate underwriting decisions.