13 July 2022 | Climate Tech

Policy to pitchforks

By

Last week, you may have seen videos of farmers protesting in the Netherlands, creating blockades with tractors, spraying manure on government buildings, etc.

You also may have seen striking videos from Sri Lanka this weekend, where nationwide protests effectively overthrew the government. The highlight may have been a takeover of the presidential palace, complete with a pool party.

Both of these protests have one thing in common. They share roots in policymakers’ attempts to regulate and change farming practices.

No, I’m not here to suggest that the Netherlands is on the same trajectory as Sri Lanka. Still, considering how much climate tech focuses on the food and ag sectors… worth taking a look, no?

Fertilizer: friend or foe?

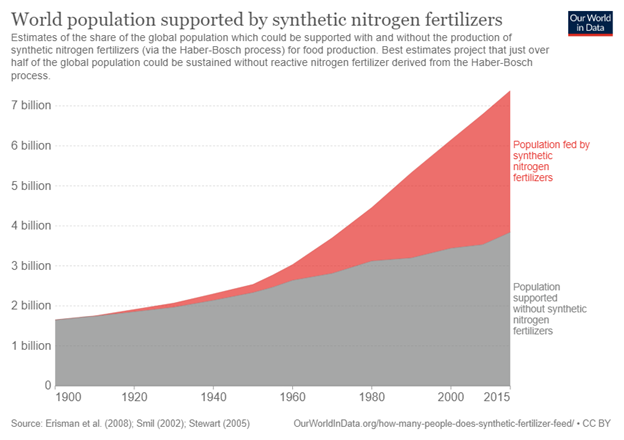

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are a miracle product. They’re one of the ingredients that have allowed global food production to keep pace with population growth over the past century. And the world uses a lot of them. In fact, more than half its population depends on them:

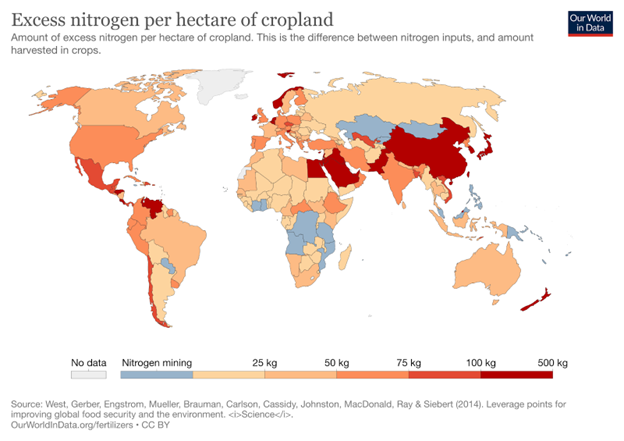

There are, of course, a few climate problems with this approach to scaling global crop yields. Up to 2.5% of all greenhouse gas emissions are nitrous oxide emissions (N₂O) from synthetic nitrogen-based fertilizer. Specifically, soil microbes produce N₂O (throughout several complicated processes) when plants and crops don’t use all the nitrogen available. This hints at a critical point, namely that the intensity of synthetic fertilizer use is a key component in the question of whether these fertilizers are friends or foes:

N₂O also has massive global warming potential – While less of it enters the atmosphere than CO2, it has 300x its global warming potential over a 100-year timespan. That’s also 10x the GWP of methane over a similar timeframe.

Further, Nitrogen and other chemicals also run off farms into rivers, a problem so pernicious that ~50% of American rivers are too polluted to swim in.

In April 2019, Sri Lanka implemented a complete ban on importing synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. Previously, the country had a vibrant tea export economy and produced a lot of rice domestically. Following the ban, farmers immediately protested. Scientists tried to warn the government about the potential consequences. And crop yields fell, but policymakers didn’t reverse course quickly enough. A million farmers’ crops failed, dropping rice output by 20%.

A 2021 USDA report summarized the failure, though it minced words:

…the lack of organic fertilizer productive capacity, coupled with the absence of a formalized plan to import organic fertilizers in lieu of chemical fertilizers, raises the potential for an adverse impact on food security.

Fast forward to today, and the costs of continuing to import more and more food in the current inflationary environment have overwhelmed Sri Lanka’s economy. There are many more factors here (three years of depressed tourism because of COVID, fuel prices). Still, the failure of Sri Lanka’s agricultural reforms is a critical case study. Shifting practices in a sector like farming must, of necessity, build in time for redundancy and for stakeholders to build expertise.

Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers are woven into the fabric of our society at this point, the same way fossil fuels are. Changing that fabric will be no small feat.

Pitchforks

Dutch farmers are similarly incensed three years after ag reforms first sparked protests in Sri Lanka. The target of their ire? Proposed emissions reduction targets for nitrogen oxide and ammonia, which primarily stem from farming operations. Specifically, new laws would target reducing nitrogen oxide and ammonia emissions by 50% by 2030. Considering we’re halfway through 2022, those would be very rapid cuts. For some farmers, the transition will be too much to handle.

These measures aren’t all about the atmosphere. While ammonia can oxidize into N2O, nitrogen deposits in the ground threaten ecosystems, and runoffs from farms pollute waterways, as discussed above . Here’s a quote from the previously linked article that puts the problem in perspective:

In 118 of 162 Dutch nature reserves, nitrogen deposits now exceed ecological risk thresholds by an average of 50%. In dunes, bogs, and heathlands, home to species adapted to a lack of nitrogen, plant diversity has decreased as nitrogen-loving grasses, shrubs, and trees move in.

So far, the Dutch government isn’t backing down, even as protests get testier, including a recent one outside the house of the minister in charge of the newly proposed policies. Dutch farmers have also blockaded distribution centers, inducing food shortages in Dutch supermarkets.

There’s no scenario in which the Netherlands is in for as tough of times ahead as Sri Lanka. But the parallels are noteworthy and point to the significant tensions accompanying many facets of what I’ll loosely call the global climate transition. If communities’ opposition to wind farms and transmission lines is any indication, getting folks on board with electrification and renewable energy is hard enough. It’ll be even harder to thread a policy need that satisfies stakeholders in essential industries like food production and climate targets.

The net-net

It’s tempting to take two data points, draw a straight line connecting them, and draw big conclusions. I’ll try to be a bit more conservative than other folks. The situation in the Netherlands illustrates that farmers need substantially more support when asked to make drastic changes to their operations. Policies aimed at emissions reductions aren’t good enough – they need to include clear pathways for all stakeholders to successfully navigate them with plenty of of redundancy & time to build expertise built in. Especially when dealing in areas like food production that society depends on.

Sri Lanka offers the worst-case scenario for making drastic changes overnight. Their situation drives home that no plan to decarbonize food and ag is complete without equal consideration for maintaining and increasing food production.

These challenges and tensions will soon spread to other countries. Whether they yield similarly explosive protests remains to be seen, but tensions are brewing elsewhere, like in Canada. German farmers are also starting to mobilize with protests of their own. This may well get bigger before it gets any ‘better.’

To end on a positive note, there are lots of companies tackling fertilizer, decarbonization, and more sustainable agriculture:

- Nitricity produces nitrogen fertilizers directly on farms using only air, water, and renewable energy as inputs.

- Better data and IoT tech to help farmers use fertilizer more smartly

- Companies like Mootral develop feed additives to reduce methane emissions from livestock.

More focus on these in the future!