01 May 2022 | Healthcare

The Next Frontier of Weight Loss

By workweek

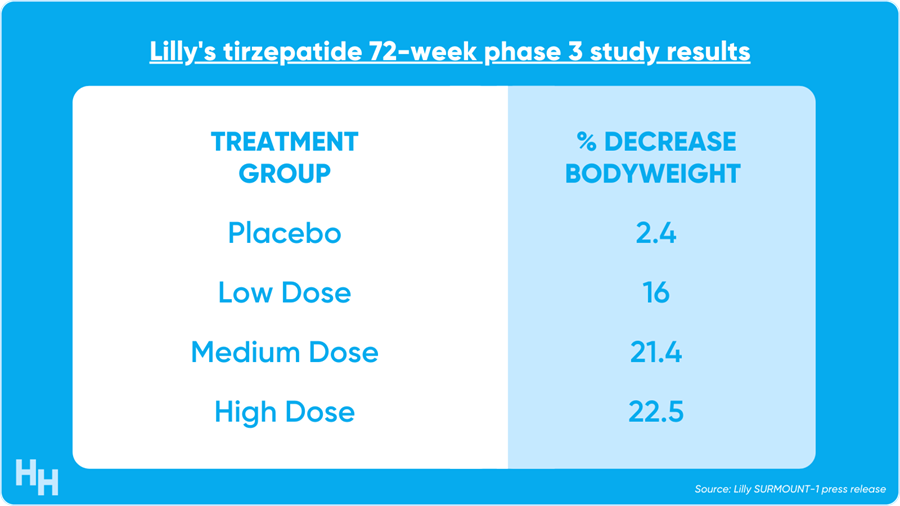

Eli Lilly’s diabetes drug, tirzepatide, led to a max 22.5% weight loss—or 52 pounds—in adults with obesity or overweight.

Some have described tirzepatide’s effects as the “equivalent of inventing nuclear fusion.” Bold statement. But I agree nonetheless that these clinical trial results are a BFD for public health.

The Deets

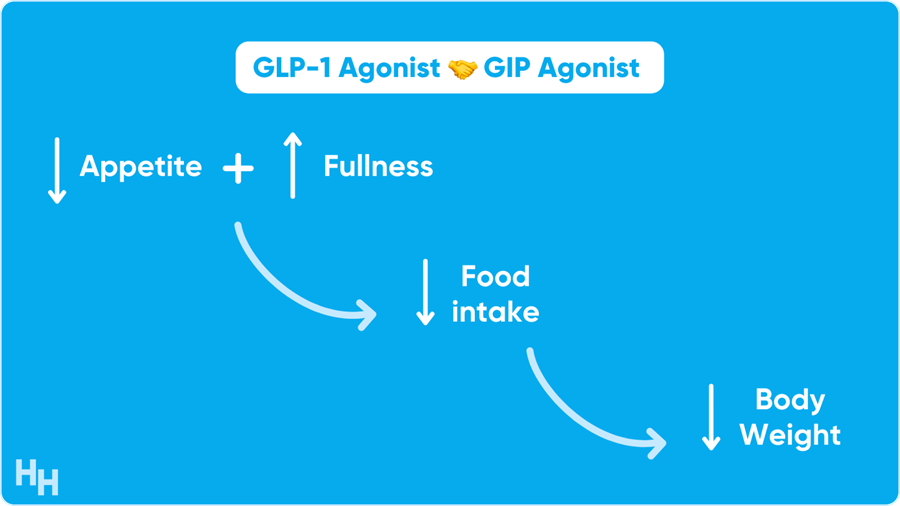

Tirzepatide is a GLP-1 receptor agonist mixed with a GIP receptor agonist. Together, these drugs work to reduce appetite, slow down food release from the stomach, increase insulin response and inhibit glucagon.

In Lilly’s phase 3 study, 2,539 participants were randomly assigned to a placebo group and tirzepatide group (low-dose, medium-dose, high-dose). After 72 weeks, participants’ bodyweight decrease on average by 16% in the low-dose group, 21% in the medium-dose group and 23% in the high-dose group. Those in the placebo group only lost 2% of their bodyweight.

One analyst predicts the drug will bring Lilly $4B in revenue at peak sales. The only comparable drug is Nova’s semaglutide—a GLP-1 analogue—which showed significant weight loss compared to placebo in a recent clinical trial. It seems that Lilly’s drug is more efficacious, but it doesn’t matter—both drugs are better than anything else on the market.

Dash’s Dissection

“Diet and exercise.”

That’s the classic response to someone saying they need to lose weight. Newsflash, it ain’t that easy. And if it were easy to lose weight, then 1.5B adults wouldn’t be overweight and 400M adults wouldn’t be obese.

While diet and exercise are effective in losing weight in the short term, it’s significantly harder to maintain weight loss in the long term. Your body works against you by increasing hormones that promote weight gain in response to a caloric deficit (e.g., dieting). These hormones remain elevated past 12 months post-weight loss. Imagine fighting your body for over a year just to prevent weight gain.

Simply put, there is a strong physiologic component resisting sustained weight loss in patients who are overweight or obese. Therefore, any subsequent weight gain, preceded by weight loss, isn’t simply because someone returned to prior habits.

The above is why medications such as tirzepatide and semaglutide will be game-changers for promoting and sustaining weight loss.

I imagine a future where tirzepatide and semaglutide will be as common as anti-hypertensive medications. The issue, of course, will be whether insurance companies decide to cover it and for which populations. The drug will likely be priced at around $5,500 per year. It seems like a cost-effective medication if the drug can prevent the expensive, omnipresent obesity-related comorbidities such as hypertension, dyslipidemia and type 2 diabetes.