There’s an inherent tension in financial services between the business of lending money and the critical role that lending plays in the functioning of our society.

As a business, lending is unusually sensitive to external conditions. When interest rates go up or the capital requirements imposed by regulators become more stringent, lenders will logically respond by pulling back; by doing less lending.

However, the demand for lending, as a social good, is far less elastic. Changing macroeconomic conditions and government regulations may impact the supply of debt capital, but the demand for it from consumers remains roughly the same. When you need a loan, you need a loan.

This tension is a source of deep frustration for community banks, credit unions, and fintech companies, many of which take a genuinely mission-centric, community-oriented approach to running their businesses.

It kills them to have to say no to prospective borrowers.

Fortunately, a great deal of innovation in financial services has been focused on making lending more broadly and predictably profitable for lenders and, thus, more accessible for borrowers.

Specialization and Scaling Social Goods

Basic economic theory tells us that specialization and division of labor lead to greater economic output and, thus, greater prosperity.

While the archetypal example of this theory is the factory assembly line, the underlying principle can, and indeed has, been applied much more broadly.

150 years ago, lending money was the sole province of banks. They aggregated capital from depositors and other investors, manufactured the loan products their customers needed, and distributed and serviced the loans.

The system was profitable and straightforward, but it was also highly inaccessible. Unless you were a wealthy individual or company based in a large urban center, your chances of getting a bank loan that you could afford were basically zero. Lending didn’t scale very well.

Take mortgages as an example.

In the early 1900s, an American family buying a house would typically pay 50% of the total purchase price upfront and finance the remaining 50% on a 3-8 year term at a rate of around 5%. Crucially, the payments made towards the mortgage only covered the interest (not the principal), and at the end of the loan term, the borrower would either pay off the principal or refinance and take out a new 3-8 year loan.

As a business proposition, this approach to mortgage lending made perfect sense. But as a social good, it fell well short of the goal that political leaders like Franklin Roosevelt, who said, “A nation of homeowners, of people who own a real share in their land, is unconquerable,” had for it.

So, right around the time that FDR was in office, we changed the system.

With the Great Depression in full swing and home values crashing, mortgage default rates shot through the roof. So the government stepped in. It purchased one million defaulted mortgages and converted them from variable, short-term interest-only loans into fixed-rate, 20-year, fully amortizing mortgages (i.e., payments went towards the principal and the interest), which were significantly easier for Americans to repay.

Consumers loved them, but lenders, which were taking significant interest rate and capital risks by keeping these loans on their books, did not.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Thus, the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) was created in 1938.

Fannie Mae’s purpose (along with Freddie Mac and Ginnie Mae) is to buy mortgages from the lenders that originate them and securitize them for investors in the secondary mortgage market, thereby injecting needed liquidity and allowing lenders to redeploy that capital as new mortgage loans.

This regulatory innovation marked the definitive pivot point in the history of the U.S. mortgage market. Mortgage lending went from a simple, profitable business that could be conducted holistically by banks to a highly complex business that can, by design, only be profitable when each step in the process is conducted by a different set of highly specialized companies and government agencies.

And while mortgages are the clearest example of specialization improving the scalability and accessibility of lending, the evolution of the broader consumer lending value chain in the U.S. over the last 150 years has definitely tilted towards specialization and division of labor.

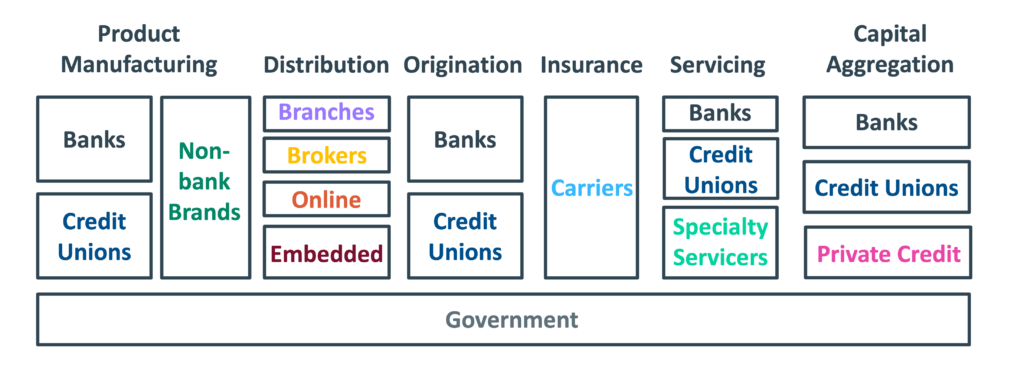

Today, almost any consumer lending product category you care to name – credit cards, unsecured personal loans, student loans, auto loans – looks less like this:

And more like this:

This increase in complexity – while it has occasionally caused problems (*cough* Great Recession *cough*) – is, overall, a good thing if you believe, as I do, that affordable loans are social goods that should be available as widely as they can safely be.

We’ve made a lot of progress in the last 150 years!

However, there’s one specific area that hasn’t seen as much innovation as I would like.

Protecting Consumers’ Ability to Pay

There are two basic components to evaluating a consumer’s creditworthiness – willingness to pay and ability to pay.

Willingness to pay is a measure of behavior. Does this consumer have a track record of managing their finances responsibly and living up to the financial obligations that they commit themselves to?

Ability to pay is a measure of circumstance. Does this consumer make enough money, relative to the financial obligations they have already made, to be able to pay back this loan?

Most of the hard work that smart people have done in lending over the last 150 years has been focused on helping lenders better understand consumers’ willingness to pay, and, more recently, making it easier for consumers to demonstrate their willingness to pay to lenders.

All of this work gave us the credit bureaus, the FICO Score, Credit Karma, credit builder products (my favorite!), and cashflow underwriting, among others.

By contrast, ability to pay has always felt a little unloved.

OK, yes, sure. We have the Work Number from Equifax and all the other income verification solutions that have popped up to support mortgage lenders. And we got a regulatory requirement to evaluate consumers’ ability to pay when decisioning them for credit cards as a part of the CARD Act. And open banking and cashflow underwriting can give us a more granular and contextual understanding of a consumer’s income history and stability.

That’s all great.

But honestly, I want more.

I don’t just want solutions to help lenders better understand consumers’ ability to pay. I want solutions that protect consumers’ ability to pay.

According to research from PYMNTS and LendingClub, 61% of all adult U.S. consumers were living paycheck to paycheck in April of 2023. That percentage was, as you’d expect, higher for consumers earning less than $50,000 per year (73%) than it was for consumers earning between $50,000 and $100,000 (63%) and for consumers earning more than $100,000 (49%). But still – it’s a strikingly high percentage overall and one that hasn’t changed much in the two years that PYMNTS and LendingClub have been doing this survey.

A majority of U.S. consumers, either by dint of insufficient income or excessive expenses (or a little bit of both), are constantly hovering on the edge of financial instability, where one good push can send them tumbling down a dark and treacherous path, populated by payday lenders and other purveyors of predatory credit products.

According to research from the Urban Institute in 2018 (when interest rates were exceedingly low), consumers with subprime credit scores (FICO Scores below 620) were, on average, likely to pay nearly $3,000 more in interest on a $10,000 used car auto loan than a consumer with a prime credit score.

This shouldn’t be breaking news to anyone reading this, but it’s worth emphasizing the point clearly – it’s expensive to have a poor credit score (or no credit score).

And we know that consumers’ ability to pay has an enormous impact on their credit scores and, thus, on their ability to access affordable forms of credit.

How do we know this?

Well, the COVID-19 pandemic provided a very useful natural experiment.

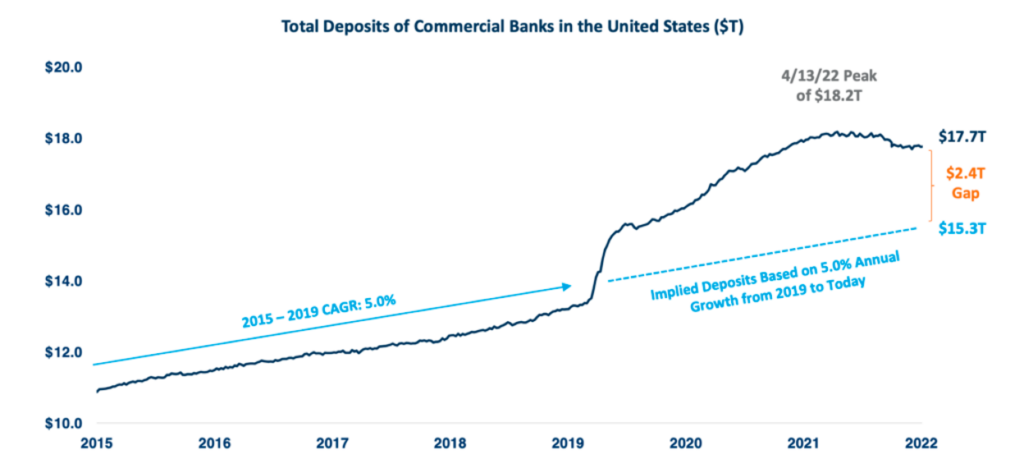

Thanks to copious stimulus and government-mandated pauses on various payment obligations between 2020 and 2022, consumers found themselves [Jean-Ralphio voice] flush with cash. According to an analysis from Tom Michaud at KBW, commercial banks in the U.S. pulled in $2.4 trillion more in deposits than they were expecting during those years:

Those excess deposits caused some problems for the banks (shouldn’t have bought those long-duration treasury bonds!), but they were enormously beneficial to consumers.

According to an analysis from the CFPB, the combination of pandemic-era mortgage forbearances, federal student loan repayment pauses, and federal cash transfers drove a notable increase in U.S. consumers’ credit scores, with subprime consumers benefiting the most:

We found that the deep subprime and subprime tiers experienced the biggest upward shift, though individuals in higher credit score tiers were also more likely to move up at least one tier than they were before the pandemic. Forty-three percent of consumers with subprime credit scores moved up at least one tier during the pandemic, whereas in the ten years prior to the pandemic, only 37 percent moved up at least one tier.

And, as you might expect, that improvement drove down the percentage of consumers that took out payday, pawn, auto title, or tax refund anticipation loans during the pandemic, according to the Federal Reserve’s Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households.

Fast forward to today, and this natural experiment is mostly over. Consumers have burned through nearly all their excess pandemic-era savings, and student loan payments have resumed.

However, the lesson that the pandemic taught me remains – proactively shoring up and protecting consumers’ ability to pay against the steady and predictable forces that erode it is one of the most effective (and underexplored) ways to increase access to affordable credit.

The question for the financial services industry is how can we protect consumers’ ability to pay without relying on billions of dollars in government stimulus?

The Missing Piece of the Puzzle

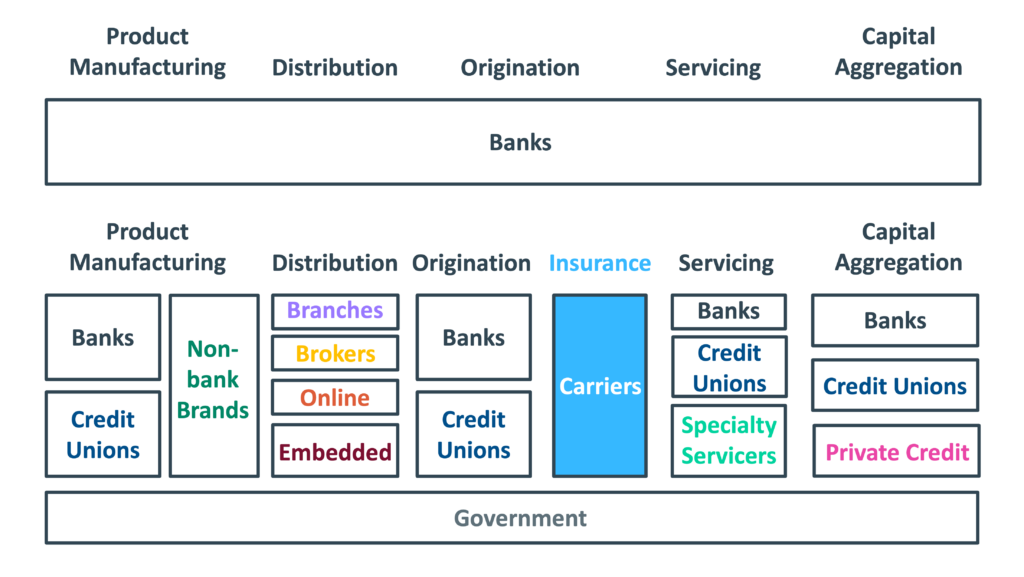

Eagle-eyed observers may have noticed a small discrepancy in the graphics I shared earlier, depicting the evolution of the consumer lending value chain – the addition of insurance.

Insurance in consumer lending is not a new concept by any means.

For decades, debt protection insurance, credit insurance, guaranteed asset/auto protection (GAP) insurance, personal mortgage insurance (PMI), mechanical repair coverage (MRC), and many more esoteric insurance products have provided a useful ‘scaffolding’ for the development of differentiated (and frequently risky) new lending products.

This makes intuitive sense.

The basic purpose of insurance is to transfer risk, and in an increasingly complex and fractured lending ecosystem populated by a large set of specialized service providers, the ability to remove risk for specific participants is essential.

Without insurance, most lenders would operate within excessively narrow credit boxes, most investors would steer clear of asset-based lending, and many borrowers would be unable to access affordable capital.

The problem is where insurance has traditionally sat in the consumer lending value chain.

Historically, insurance was used either as a risk transfer mechanism on the back end of the value chain, often between lenders and investors, or as an add-on product sold directly to the borrower on the front end.

Neither place is ideal for serving the goal of safely making affordable credit more widely accessible.

When insurance becomes an abstract product, solely used between sophisticated intermediaries to push their leverage or collect excessive fees, you get a situation very much like the one AIG found itself in after selling piles and piles of credit default swaps on mortgage bonds in the early 2000s.

When insurance is a consumer-facing add-on product, able to generate additional revenue for lenders and their distribution partners, you get a situation very much like the one that consumers find themselves in whenever they go to buy a car and end up getting dragged into the F&I guy’s office for an hour-long cross-sell session (fun fact – finance and insurance products now drive more profits per new vehicle for auto dealers than the sale of the vehicles themselves.)

What I want, and what I think the consumer lending value chain needs, is an insurance product that protects borrowers’ ability to pay from specific, insurable risks like job loss or disability. The product shouldn’t be distributed as an add-on, sold by loan officers or insurance brokers, but rather embedded within the loan as a standard feature. And most importantly, the product should de-risk loans so that secondary market investors are more likely to buy them, enabling lenders to turn around and lend more (much in the same way that homeowners insurance creates a more liquid mortgage market).

Creating Trust, Protecting Relationships

Too often, we reduce lending down to a simple accounting and risk management exercise, measured using metrics like customer acquisition cost, loan-to-value ratio, and net charge-off rate.

In doing so, we forget a very simple and important truth – lending, in any form, is fundamentally a relationship business, and the most important investments in that business will always be those that build trust and strengthen relationships.

Dennis Cail is the co-founder and CEO of Zirtue, a digital platform that streamlines lending between friends and family. Cail’s motivation for starting Zirtue was rooted in his experiences growing up in low-income public housing in Lousiana and his experience, later, serving in the Navy, where he had ample opportunity to see the disastrous impact of predatory lending on service members:

When I got out of the Navy, I told myself that if and when I had the time and resources to chip away at the problem of predatory lending, so that people who come from underserved communities like the one I come from, can get fair and equitable access to capital without paying a 400% interest rate, then that’s what I was going to do.

Zirtue provides a better alternative by helping to bring structure to the informal practice of friends and family lending, which happens in the U.S. today at a rate of about $200 billion a year.

The Zirtue platform removes the awkwardness of arranging a loan between friends or family by enabling the lender to determine a loan amount (the average is about $600), set a payback period (the average is six months), and (if they want) to ensure the loan is going to a specific biller by having the funds directly transferred by Zirtue to the biller.

Zirtue collects a small processing fee from the lender or biller for each loan. All loans on the Zirtue platform are 0% interest.

A new feature of the loans made through Zirtue’s platform is Payment Guard Insurance (provided by TruStage™), which helps protect lenders if their borrowers experience covered unknown job loss or disability. According to Cail, the decision to embed Payment Guard Insurance was a no-brainer:

We don’t charge interest on our loans, so we don’t have an incentive to maximize yield. Our only incentive is to do everything possible to protect the relationships between the lenders, borrowers, and billers on our platform. We don’t want to put a borrower who has just been laid off from their job in the position of having to choose between paying back a family member or paying their rent. Our billers don’t want to be in the position of disconnecting a customer’s electricity or damaging their credit score because their ability to pay has unexpectedly been disrupted.

There are lenders out there who will take advantage of people who have just lost their jobs. And there are lenders out there who won’t lift a finger to help people who have just lost their jobs, no matter how financially responsible they are. We want to enable a different kind of lending, and lending insurance is an important catalyst for that.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very carefully curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by TruStage.

TruStage is a financially strong insurance, investment, and technology provider, built on the philosophy of people helping people. We believe a brighter financial future should be accessible to everyone, and our products and solutions help people confidently make financial decisions that work for them at every stage of life. With a culture rooted and focused on creating a more equitable society and financial system, we are deeply committed to giving back to our communities to improve the lives of those we serve.

Alex Johnson may receive compensation from TruStage for this advertisement.