If you haven’t listened to this podcast that Jason Mikula and I did with Mark Gould, the Chief Payments Executive at the Federal Reserve, I would highly encourage you to do so.

It was fascinating.

We recorded it shortly before the July 20th launch of FedNow and, as you might imagine, faster payments was a big part of our discussion. However, we also covered a lot of other ground, including the organization and role of the Federal Reserve as a financial services infrastructure provider, the enduring value of cash, and the impact that new payment rails have on existing ones.

Coming out of this conversation with Mark, I had a ton of notes in my notebook – half-baked ideas, burning questions, idle observations – which will undoubtedly influence future essays in this newsletter.

But in the meantime, I thought it might be useful to just share my notes with you directly, in their raw and unprocessed form.

The Federal Reserve’s Most Underrated Job

The Fed has a bunch of different jobs.

Some of them are very well-known (monetary policymaking). Others only pop up on the radar screen when something goes wrong (regulating and supervising banks). But there’s one that gets hardly any attention, despite its enormous importance – providing retail and wholesale payments capabilities (physical cash, check processing, ACH, wires, etc.) to financial institutions.

The exact nature of this job has evolved quite a bit over the years (the Automated Clearing House network was created in 1972), but the scope of what the Fed supports today is truly staggering. On an average day, the Fed processes roughly $5 trillion in payments volume across a network of 10,000 financial institutions!

When Mark shared that fact, I almost fell out of my chair. I knew it was big, but $5 trillion a day?!? Whoa!

The Fed’s Evolution Jumps Ahead of Banks’ Evolution

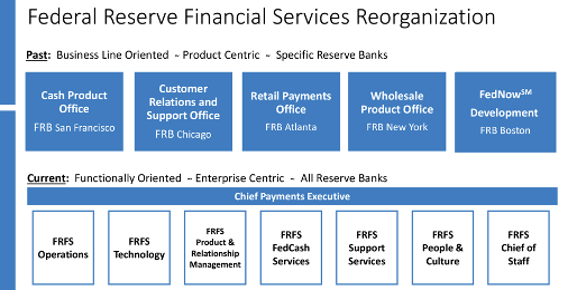

Another thing I didn’t know until speaking with Mark – the payment services provided by the Fed were historically run out of specific regional Federal Reserve Banks. Cash was run out of San Francisco. Retail payments were run out of Atlanta. Wholesale out of New York. And even the development of FedNow, which the Fed started noodling on around 2013, was run out of Boston.

The evolution of this regional approach mirrored the evolution of banking in the U.S. more broadly. As interstate banking took off in the late 1990s, the Fed’s payment services evolved from being a truly decentralized set of services delivered at a local level to becoming more nationalized. However, the underlying structure of the Federal Reserve Financial Services organization remained siloed. Specific regional Reserve Banks still retained their roles as the ‘operational nerve centers’ for specific payment products.

Until a couple of years ago, when the Federal Reserve reorganized its Financial Services organization to move completely away from product silos and embrace a functionality-oriented enterprise model.

Here’s how Mark described the rationale for making this change:

Customers were experiencing us as five different organizations even though we were a single one, and we really needed to focus on the customer experience and start delivering a service that was more consistent.

This is remarkable if you think about it. The Federal Reserve Financial Services organization evolved from a local, branch-based structure to a nationalized, product-centric structure to an enterprise, customer-centric structure.

That’s more evolved than most banks, which are still stuck in product silos!

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Cash’s Value

Cash occupies a unique position within the Fed’s portfolio of payment instruments.

While it is a tool for conducting transactions, it is also a store of value.

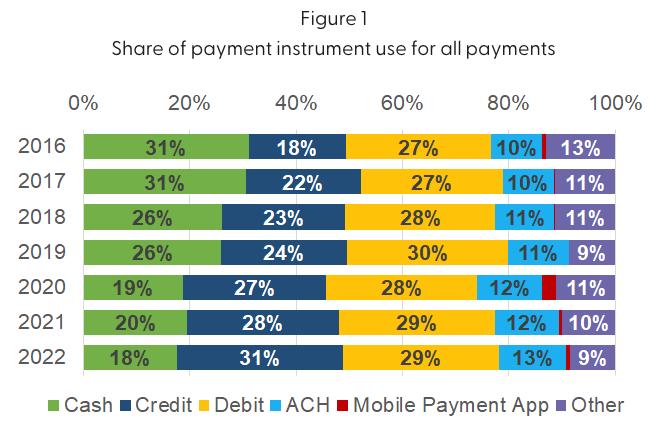

And while the transactional use of cash has been declining:

The use of cash as a store of value has been increasing.

Indeed, according to the Fed, the average American household has twice as much cash on hand today as they had before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

And, of course, the U.S. dollar is incredibly popular as a store of value in other countries. Federal Reserve Board economist Ruth Judson estimates that more than 60% of all U.S. bills and nearly 80% of $100 bills are now overseas—up from 15% to 30% around 1980.

FedNow Will Be Additive

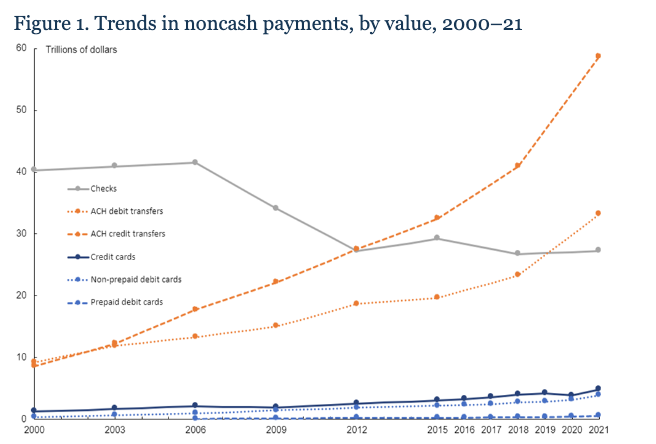

My assumption, when it comes to the introduction of new payment rails, is that their success will come, to a degree, at the expense of existing rails.

The increasing usage of ACH (particularly ACH push transactions) and the declining use of checks over the last 20+ years is a good example:

My assumption is that FedNow will have a similarly disruptive effect.

Mark, who has a touch more experience with this stuff than I do, sees it a bit differently:

My personal view is that the total number of payments made in the country are going to skyrocket in the next decade or two. … I think the availability of instant payments will increase the total size of the pie.

This is really interesting!

I guess the theory here is that FedNow, with its unique characteristics relative to other payment rails (speed, availability, finality), will unlock a lot of net new payment opportunities, and while there will be some reshuffling of payments volumes across different rails, the overall amount of payments will go up.

ACH Wasn’t Built to be a platform. FedNow is.

The ACH network was built in 1972. Obviously, at that time, the idea of designing an electronic payments system that could be extensible and that allowed third-party developers to build valuable applications on top of it didn’t exist. They were just trying to digitize the process of sending money from one bank to another, and the system you got was the system you got.

A lot of innovation in financial services since 1972 has come from finding novel ways of getting the ACH payments system to do things that it wasn’t natively designed to do. A lot of those innovations are less about technology and more about risk management.

For example, 2-day early access to your paycheck is, under the surface, a pretty simple innovation. Your bank is just floating you the money once an ACH transaction from your employer has been initiated and accepting a bit of credit risk while waiting for the transaction to settle.

Over the long term, I anticipate that FedNow will knock down a lot of the rickety scaffolding that has been built around ACH. This will render certain value propositions like 2-day early access to paychecks irrelevant, but it will also open the door to new, more tech-driven innovations being created.

One of my favorite quotes from Jason and I’s conversation with Mark came when he was describing the development of FedNow and how the first couple steps in that development have been laser-focused on building the service and driving adoption of it:

The third step, and the one I’m most excited about, is leveraging FedNow as a platform for innovation. … There are a lot of companies already thinking about how they can leverage this platform to provide really interesting services to financial institutions.

The Fed is Leaving It Up to Banks

FedNow is infrastructure.

U.S. financial institutions are free to use it or not. And they have total flexibility to build whatever products and services they want on top of it and to charge however they want for those products and services.

This is very different than how instant payments in other countries works.

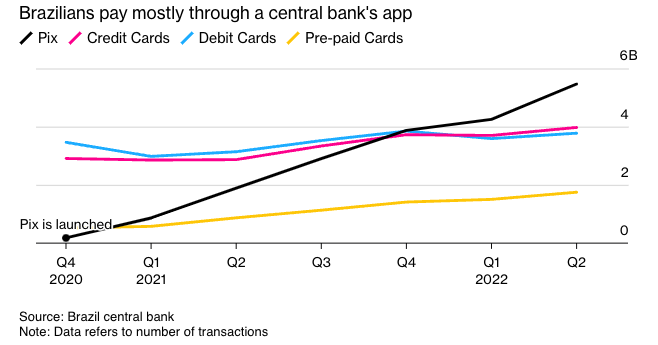

Take Brazil, for example, where the central bank introduced a similar real-time payments rail called Pix in late 2020. The service, which the big banks are required to support, enables free P2P transactions as well as instantly settled transactions between consumers and merchants, which are free to the consumer and relatively low cost for the merchant.

Pix is Visa and Mastercard’s worst nightmare:

Now, of course, U.S. banks could choose to leverage FedNow and other faster payments mechanisms to deliver a similar value proposition to consumers and merchants.

But, without the same type of government mandate that we see in countries like Brazil and India, will they? Will they really choose to push account-to-account payments over the more lucrative debit and credit cards they already offer?

The contentious debate within JPMorgan Chase over this exact question makes me skeptical, to say the least.

A Lot of the Use Cases Will Require Giving Up Value or Charging for Value

One thing I’ve always wondered is, Why didn’t EWS choose to charge customers a fee for real-time P2P transfers through Zelle?

I know EWS wanted Zelle to stand out, compared to Venmo and Cash App, but the reality is that while all P2P payments require the appearance of happening in real-time, very few actually require the money to move instantly. It has always seemed to me that EWS caused its banks a lot of headaches by making Zelle payments instant by default (hello fraud!) rather than offering instant payments as a paid option (for use cases like paying your rent the day before it’s due).

The reason I bring this up is that I think a lot of value is wrapped up in the fact that established payment mechanisms are either slow or expensive. In other words, if you want money fast, you need to pay for it.

Faster payments disrupts this.

If, by default, money can move instantly for a cheap price (the Fed has to charge a little for FedNow to cover its costs, but it’s not trying to make a huge profit), what impact does that have on this speed/cost dynamic? Will companies choose, like EWS, to give away the value of speed for free? Or will they price it based on its value and pocket the extra margin created by FedNow?

One Foundational Rule of Payments Will Remain Unchanged

Regardless of how we continue to upgrade our payments infrastructure, one foundational rule of payments will remain unchanged – the party that has the most leverage in the transaction will dictate the payment mechanism(s) used to conduct the transaction.

This rule is why most vendors at a farmers’ market accept all debit and credit cards, but Costco only accepts Visa. Costco has leverage.

My guess is that this rule will determine which instant payments use cases migrate to high-cost payment rails (cards) and which use cases migrate to lower-cost ones (FedNow). When the party with the most leverage is the one that benefits from the higher cost, they will impose it rather than seek out a lower-cost alternative.

A good example is insurance claims payouts. There’s obviously a value to making that payment instantly, but the leverage sits with the insurance carrier (consumers and small businesses are happy when they can get their carrier to pay at all!) As a result, I would expect that instant payments in insurance will likely be enabled through one-time virtual cards (which generate interchange for the issuer) rather than FedNow.

For instant payments use cases where the leverage sits with the party incurring the costs, we may see a migration to FedNow.

Fighting Fraud Will Require More Friction

Fraud is a big concern with faster payments.

In our conversation, Mark emphasized the importance of consumer education in fighting fraud as well as the development, over time, of fraud mitigation capabilities directly within the FedNow platform.

I agree with him about the importance of consumer education. I also think we need to reframe how we talk about the trade-off between convenience and safety in financial services.

When you take a step back, it’s a bit strange that the history of fintech, to date, has been mostly a history of building incredibly seamless and convenient user interfaces on top of really old technology. It’s like installing a remote-controlled garage door opener for a horse-drawn carriage.

Now the Federal Reserve is upgrading us from a carriage to a Shelby Cobra, and the question is, How do we keep people safe?

My guess is that the user interfaces that we’ve wrapped around our payments infrastructure will evolve to become more thoughtfully designed and will include a lot more points of friction intended to slow users down and help them avoid irreversible mistakes.

We’ll go from building UIs that encourage customers to act without thinking to UIs that require customers to think before acting.

Achieving Ubiquity Will Take Time

FedNow is the first new payment rail that the Fed has launched in the last 50 years. That’s exciting! All the potential value of FedNow that I’ve covered in this essay and that we covered in the podcast is very exciting!

However, it’s important, as Mark himself said in our interview, to temper that excitement. At launch, FedNow had 41 banks and 15 service providers integrated. It’s going to take quite a while to get every other financial institution in the U.S. integrated, but, as Mark made clear, that is the metric that he and his team are marching toward:

Success in the long term is the ubiquitous availability of instant payments in the United States. Nothing short of that is going to be a success, and we’re determined to get there.