Do you hear that?

That dull, almost imperceptible roar? Like a giant engine quietly idling? Or a massive storm, just creeping over the horizon?

Yeah, what you’re hearing there is actually the sound of thousands of banks jostling with each other over deposits.

The Wall Street Journal reports:

Deposit costs jumped sharply at all four banks that reported on Friday, which also included Citigroup. On average, the rates on interest-bearing deposits were around a fifth higher than they were in the first quarter. That was a slower pace of increase than from the fourth to the first quarter. However, base interest rates set by the Federal Reserve didn’t rise as much during the second quarter—so the pace of deposit-rate increases accelerated relative to the increase in the average federal-funds rate.

No banks are safe from the pressure, it appears. In response to a question on Friday from analysts about customer demands for higher rates, JPMorgan Chief Executive Jamie Dimon warned everyone to anticipate more on this front. “There is very little pricing power in most of our business, and betas are going to go up,” he said, with “beta” referring to how much of an increase in base interest rates banks pass along to customers. Brian Foran, an analyst at Autonomous Research, wrote in a Friday note that this outlook coming from the biggest bank in the country was “a definite curb your enthusiasm moment.”

And it’s not just interest-bearing deposits that banks are struggling to retain. Here’s the journal again:

there continued to be a shift out of banks’ “golden” deposits, which are those that collect no interest at all. Excluding JPMorgan, whose numbers were skewed by taking on First Republic Bank’s customers, overall deposits at the reporting banks on Friday were down 1% quarter-over-quarter by period end. Non-interest-bearing deposits were down over 7% at those same banks. That increases banks’ deposit costs even beyond what their average deposit rates indicate.

Cheap deposits – a feature of the modern banking landscape, a resource that became so overflowingly plentiful that banks almost drowned in it during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic – are disappearing.

The Federal Reserve’s campaign of quantitative tightening has led to a significant increase in competition among banks for retail and commercial deposits. This is challenging for banks in the way that rising interest rates are always challenging for banks (managing the costs to acquire and retain deposits in order to protect net interest margin and maintain adequate liquidity), but it’s also challenging in a completely new way (the last time banks were operating in a sustained rising/high rate environment, we didn’t have smartphones or open banking or fintech).

This has cast a cloud of uncertainty over the industry.

No one really knows exactly how depositors will behave. All we know, thanks to Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic, is what it looks like when things go catastrophically wrong.

This is the backdrop for the Q2 earnings that banks, big and small, have been reporting over the past week or so, and it seems to me a good time to take stock of banks’ current thinking on deposits and to propose a few questions for them to think more deeply about for the future.

To help me do that, I’m going to draw on public comments made in the Q2 2023 earnings calls of some regional and super-regional banks, as they are, no offense, much more interesting than the big four.

What are large regional banks thinking about right now?

Remix!

One trend that we seem to be seeing across the board is a shift in the mix of deposits that banks have, from non-interest-bearing accounts (the “golden” deposits that the WSJ referred to above) to interest-bearing accounts (interest-bearing checking accounts, savings accounts, CDs, etc.)

Not surprisingly, this shift is much more pronounced among commercial deposits as opposed to retail deposits. This makes perfect sense, as companies tend to be more disciplined in maximizing the return on idle cash than consumers.

Join Fintech Takes, Your One-Stop-Shop for Navigating the Fintech Universe.

Over 36,000 professionals get free emails every Monday & Thursday with highly-informed, easy-to-read analysis & insights.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Here’s PNC:

Deposits continue to move from non-interest bearing to interest bearing accounts. As expected, the mix shift is being driven by commercial deposits. In the second quarter, commercial non-interest bearing deposits represented 45% of total commercial deposits compared to 47% in the first quarter. Our consumer deposit non-interest bearing mix has been stable remaining at 10%.

This remix obviously leads to higher deposit costs, as banks go from paying no interest to paying interest. Additionally, all banks are reporting that the amount of interest that they are being forced to pay on interest-bearing accounts in order to attract and retain customers is also increasing, leading to higher deposit betas (the percentage increase in base interest rates that banks pass along to customers).

Primacy, Operating Accounts, & Relationship Banking

Of course, in order to maximize profit, banks want to find ways to retain customer deposits without having to pay more for them. There are a couple of different ways that they talked about doing this.

The first is primacy. Here is Citizens Financial Group bragging about the impact that simple neobank innovations have had on its ability to establish engaged primary banking relationships with retail customers:

So we did things like get your paycheck two days early. It doesn’t seem like a big deal, it’s actually an incredibly big deal. That’s driving a lot of primary banking behavior. We’ve got technology we put in place that when you open a new DDA, you’re automatically porting over your direct deposit that seems very operationally oriented. But it actually is a dramatic improvement that things like primary banking behavior which drives low-cost deposits.

We’ve made overdraft perform through our Peace of Mind 24-Hour Grace program and a variety of other things, which has also driven a lot of primacy

Who knew? You give customers their money faster and don’t penalize them for every little mistake, and they are more willing to stick with you (without requiring a bribe).

This same general thinking applies to the commercial side as well, but the big difference is that in order to retain commercial deposits (which tend to be more rate-seeking), banks need to retain those companies’ ‘operating accounts’ (i.e. the demand deposit accounts that they use to make payments and run their business). A good example here is Fifth Third, which has made a number of acquisitions recently in order to build out its embedded payments business for commercial customers. This is really smart as it not only provides a new business for Fifth Third to grow and monetize directly, but also serves to make Fifth Third that much more of an operating hub for its commercial customers, and, thus, a sticky home for those customers’ deposits.

And finally, we see some of these banks insisting that their commercial customers acquire both lending and deposit products from them, thus capturing the entire relationship. Here’s Western Alliance Bank describing this new approach:

we are looking at a full client relationships and we are not — no longer just giving credit and then worry about how we fund it away from the client. The client needs to have a full relationship with us.

You may remember SVB employing a similar strategy, which, of course, didn’t save them when all their customers decided to sprint to the lifeboats.

Speaking of which …

Reassurance

Unlike its super-regional and national bank peers, smaller regional banks like Western Alliance have to worry about a similar panic to the one that took down SVB and, in a less dramatic fashion, First Republic. Hence Western Alliance’s repeated focus stability in its earnings presentation:

we have actively utilized reciprocal deposit channels to drive growth and provide greater insurance coverage to larger depositors. 62% of broker deposits consist of sticky reciprocal deposits. We believe these core client relationships have been fortified through this product enhancement, making them exceptionally stable.

Reciprocal deposit arrangements, in which funds received by a bank through a deposit placement network in return for placing a matching amount of deposits at other network banks, are a very effective tool for expanding customers’ effective FDIC insurance coverage beyond the standard $250,000 limit.

By providing reassurance, Western Alliance believes that it can kickstart a positive feedback loop with commercial depositors, who will feel confident enough to bring their business back to the bank:

We are seeing that pipeline reappear, it’s stronger. … a lot of people wanted to wait until we were announcing our quarterly earnings. I think that will make people feel comfortable and we have some great deal of comfort on that pipeline returning, which gives us comfort to the $2 billion guide that we have put out there for deposit growth.

Customers Have Less Money

This one is simple, but it’s a good reminder. Beyond rising interest rates, part of the challenge for banks’ deposit franchises right now is simply that their customers, particularly their retail customers coming down off of pandemic-era stimulus, have less money (and spend less money) than they did a few years ago.

Here’s how Fifth Third described it:

So in terms of consumer on the household side, we do have a very strong and consistent growth of 3%, but offsetting that tailwind is the headwind from consumer spending and the declines in the average deposit balance. So when you look at the consumer, the average deposit is still 20% higher than pre-COVID levels, but it is down 10% from the COVID average balance peaks.

Translation? Customers are still better off today than they were pre-Covid, but that margin is shrinking.

I also found this fascinating:

Consumers have held up well in aggregate, but there has been a divergence between homeowners who were able to lock in historically low mortgage rates and renters who have had to face persistent inflation in their largest monthly expense. Compared to three years ago, homeowners in our deposit base have maintained strong deposit balances, whereas renters deposit balances are down meaningfully.

What questions should all banks be thinking about for the future?

The overarching feeling that I got, reading through a lot of the bank Q2 earnings call transcripts, was a kind of forced calm, as if the CEOs and CFOs at these institutions were trying to reassure market analysts (and themselves) that they have a good handle on customers’ evolving deposit behaviors.

Here’s M&T Bank’s CFO, framing it as a simple return to the pre-ZIRP days:

if you go back 20 plus years and you look at the deposit that we had back then, CDs were 20% plus of our funding base. Right now, we’re at 10%, and we’re probably going to be in the mid-teens before it’s all said and done, it really depends on how long rates stay higher. And that’s just the normal mix of how we run our retail bank.

I mean it’s the right thing to do. It’s the right thing for our clients. It’s the right thing for our bank. We can adjust our rate sensitivities with CDs on the books and manage that really well. So it’s just basically learning things that when you ran banks 20 years ago, we’re doing the same thing right now and doing it the same way.

This is what I would have expected. C-level executives at banks are paid to project an air of confidence in public. They’re not going to dial into earnings calls and say, “Well, we had a pretty decent quarter, but we really have no fucking idea what’s going on or what’s going to happen next.”

(Related – one amusing thing from all of the earnings calls I reviewed was the banks reporting that, relative to the first two months of Q2, June was a surprisingly good month for deposit growth, for reasons they couldn’t explain. They were basically just like, “Whelp, we hope this trend keeps up in Q3!”)

However, behind closed doors, I expect that bank executives are thinking deeply about some fundamental questions about the deposit side of their business, including:

Where are all of the commercial operating accounts, and how do we get them?

In much of the Q2 earnings commentary, I was struck by the repeated references to niche commercial banking market segments and the focus that banks have on cultivating them. Here’s Western Alliance:

we will see growth come for the rest of the year in business escrow services, in settlement services, in HOA. By the way, those are three standalone deposit channels, which we have been developing over the past couple of years

And here is Citizens, bragging about the same thing:

on the product side, we’ve done a lot around green deposits and carbon offsets deposits in our ESG strategy that was approved to be quite profitable. We’ve built out escrow products and bankruptcy products. So there’s a variety of product development things which are attracting nice operating deposits with some nice breadth for them.

None of these commercial segments are all that large or (likely) all that profitable, but the reason that banks are so focused on them is that, in the aggregate, they represent a very sticky source of deposits. A company that is providing escrow services is, by its very nature, going to have very stable deposits because those deposits need to stay in those escrow accounts! HOAs are an even better example. It’s literally just a sleepy little operating account that homeowners pay dues into, and that occasionally gets drawn upon for specific expenses/investments.

These niche commercial operating accounts are now the hottest commodity in banking.

In a similar vein, I predict that we are going to see more mid-size banks follow in Fifth Third’s footsteps and attempt to establish new, innovative models for facilitating commercial payments. Much of this innovation will fall into the realm of embedded finance and banking-as-a-service, with the banks acting as indirect enablers of new commercial banking, payments, and expense management services (and providing the balance sheets for all of the resulting commercial deposits).

How has technology changed deposit behaviors?

This question has been brought to the forefront by the failure of SVB and the role that digital banking technology (and social media) played in its rapid demise. However, the implications of this question are much broader – how will the convenience, speed, and intelligence enabled by digital technology change the value of banks’ deposit franchises?

Well, let’s take those one at a time.

First up – convenience.

Do digital innovations like mobile banking decrease the stickiness of bank deposits and, thus, reduce the value of banks’ deposit franchises?

According to a recent academic study published by the Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State University of Chicago Booth School of Business, the answer is yes:

Since the Great Financial Crisis, over half of the roughly 4,000 existing banks have introduced a mobile app. Thus, moving money from a deposit to a money market fund can be done with a single mouse click without leaving your sofa. As a result, it is reasonable to expect that the demand for bank deposits has become much more sensitive to the interest rates offered by alternative forms of liquidity storage (like money market funds), especially in banks with well-functioning digital platforms.

Having obtained an estimate for two of the key parameters of the … model of the value of deposit franchise, we can estimate that the value of deposit franchise is 40% lower in digital banks.

Next up – speed.

Would the ability to move money instantly, on any day and at any time, place additional stress on the liability side of banks’ balance sheets?

I haven’t seen any academic research on this question (yet), but it certainly is something that folks are concerned about, as the Wall Street Journal recently reported:

Speedier transfers carry another potential cost for banks. In addition to losing revenue from the time between a payment’s initiation and settlement, banks now have to worry about deposit flight outside of business hours. It comes just months after three major lenders failed in part because of rapid withdrawals and an inability to tap emergency sources of cash that were offline.

instantaneous transactions allow customers to pull cash with ease, and without notice. That threatens smaller banks and likely requires stiffer cushions to mitigate adverse scenarios, according to [Noor] Menai, an advisory council member of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

I personally find concerns about the impact of faster payments mechanisms like FedNow on bank stability to be a bit overblown (if you’re dependent on 2-3 days of float to cover routine liquidity scenarios, you’re driving too close to the cliff), but certainly, it doesn’t make building a stable deposit franchise easier.

(BTW, Kiah Haslett and I cover this topic in a lot more depth in our most recent Bank Nerd Corner podcast.)

And finally – intelligence.

As bank accounts and money movement infrastructure become more intelligent and programmatic, what impact will that have on deposit acquisition and retention?

That’s obviously a broad question, so let’s anchor it on something more specific and timely – open banking.

The CFPB has made it clear that its primary goal in formalizing open banking in the U.S. (via rulemaking on Dodd-Frank 1033) is to decrease switching costs for consumers’ transactional banking accounts:

In an open and competitive market, it is easy for individuals to fire, or walk away from, their financial provider for whatever reason. For example, for most consumers, changing a bank account is a huge pain. Direct deposits need to be reset, as do scheduled payments linked by ACH or debit card. And consumers need to take these actions, while managing day-to-day liquidity issues. Our rule will facilitate third party companies that offer services to make switching recurring payments easier.

A competitive market would also lead to unbundling where companies compete on individual products, rather than relying on captive customers or cross-selling scams. When markets aren’t competitive, we feel that we need to buy additional services from a provider we already worked with. But with more seamless integration, this will give us all more choice.

more switching would lead to greater efforts by firms to maintain or win customer loyalty.

If you’re a bank executive thinking about how to build a durable moat around your retail deposit business, those words from Director Chopra are abjectly terrifying.

Will all retail customers become deposit optimizers?

So, technology has (and will continue) to make it easier for consumers to open new accounts, move money, and, generally, optimize their cash on hand, in the same way that a team of treasury management professionals do for a large corporation.

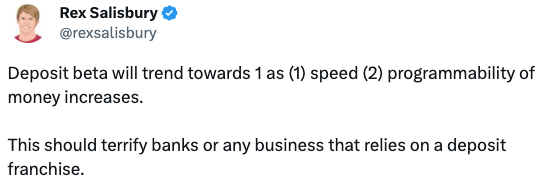

Does that mean that all retail bank customers will take advantage of this technology? Are we destined, as my fintech friend Rex Salisbury posited on Twitter, to end up in a world where banks are completely unable to retain deposits if they don’t pass 100% of every rate increase on to their customers?

Ehhh … I’m not so sure.

For commercial deposits, yes. I think this is where we will end up.

The reason that VC-backed startups banking at SVB had large balances of uninsured cash sitting in their accounts was purely a function of bandwidth. Startup founders don’t have the time or expertise to moonlight as treasury management professionals, even though they do have a fiduciary responsibility to do so.

This problem will be solved by technology. All of those ‘CFO in your pocket’ products that we have seen roll out in the B2B fintech space in the wake of SVB will help push all companies, regardless of size, towards a more well-optimized end state. Acquiring sticky deposits in the commercial space will become, almost entirely, an exercise focused on operating accounts.

I’m not so sure this same trend will play out in the retail deposits space, even with the benefit of open banking and fast, programmable money movement.

Consumers are weird. They value the status quo in ways that are difficult to understand or model from the outside. They don’t switch banks nearly as often as they should or even as they say they would, even as the cost of switching is reduced.

This is deeply unintuitive to regulators (who are naturally distrustful) and VCs and tech startup founders (who are natural optimizers), but I do think there is (and will continue to be) some truth to it.

What role can branches play in the deposit wars to come?

My naive, fintech-y assumption would have been not much. In a digital-first environment, branches are more of an inconvenience that bank customers (both retail and commercial) are forced to deal with rather than a competitive differentiator for the banks that operate them.

Turns out that maybe both things are true!

In a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper titled, “Bank Branch Density and Bank Runs,” researchers point out that banks that spend money on technology tend not to spend as much money building branches and that those banks have a more difficult time holding on to deposits:

banks with low branch density attract largely uninsured deposits through digital banking. Digital banking services provide convenience and speed, which appeal to both corporations and tech-savvy households with large funds to deposit. … We find that banks that made large investments in IT had lower branch density in 2022, with a one standard deviation increase in IT investment corresponding to 1.4 fewer branches per $1 billion of deposits (15% of the unconditional mean of branch density).

Lower branch density allows banks to attract deposit flows and expand funding capacity. However, low branch density also lessens the value of the bank-depositor relationship—shifting the depositor base to corporations and tech-savvy depositors with large, mostly uninsured deposits. These changes to the composition of the depositor base turn out to be detrimental during market downturns: banks with lower branch density experience larger deposit outflows and worse stock performance.

The argument made by this paper is that branches are useful for building durable deposit franchises, not despite the inconvenience that they impose on customers, but rather because of the inconvenience they impose on customers.

The inconvenience, when paired with poor digital banking capabilities, is a feature, not a bug!

The potential implications here are fascinating. Should banks be investing a lot more in branches? Can banks simultaneously build strong digital capabilities to facilitate the rapid gathering of hot deposits and new, dense branch networks where there is an opportunity to acquire stable, insured, less-tech-savvy deposits?

Fifth Third (who is really fucking smart about this stuff) seems to think so:

We have added over 70 de novo branches in our Southeast footprint since 2019, more than any other bank except JPMorgan. As a portfolio, these branches are outperforming their original business cases on deposit production with several producing at a rate of 200% to 300% of plan.

How much, if at all, do customers value their overall relationship with us?

Relationship banking, as the foundation for maturity transformation, has been the way that bankers (and bank regulators) have thought about their industry for a long time.

We invest in deep, high-value relationships with our customers, relationships that they value. And that value affords us with a certain amount of confidence that those customers’ deposits won’t just disappear tomorrow, even though, contractually, they could.

I do think there is something to this theory. It feels correct. But damn, it is hard to quantify.

How do you value a relationship with a bank?

- Is it personal? The relationship you have with the person at the bank who you routinely interact with? Would you choose not to move your money to a higher-interest deposit account if it meant disappointing a friend? Is this model completely dependent on the in-person experiences of a branch, or can it be somehow replicated in other channels?

- Is it about advice? The guidance you receive from your bank on how to manage your finances and build wealth? Genuine question – does any bank (or fintech company) offer such uniquely good financial advice that it can serve as a competitive moat?

- Is it about the perks? The ski retreats and wine tastings and interest-only jumbo mortgages? Does offering outrageously generous benefits, for the transparent purpose of attracting wealthy customers, lead to a genuine relationship between equals?

- Is it about the bundle? The Amazon Prime-like combination of integrated features and benefits that make it intolerable to work with anyone else? Banks have pursued a universal banking vision, bound together by cross-sell and multi-product relationships, forever, but has any bank (or fintech company) actually figured out a multi-product bundle in which 1+1=3?

Banks will (and should) factor relationship strength into their liquidity management and deposit retention strategies. I’d just encourage them to do so with a healthy amount of skepticism and humility.

The Fog of War

Banks are in a war for deposits.

They didn’t start the war (the Federal Reserve did), and they can’t end it (only the Federal Reserve can). All they can do is fight it, to the best of their abilities.

The winners will be those that can most effectively apply the lessons of the past without letting dogmatism dictate their strategy for dealing with an uncertain future.