28 April 2023 | FinTech

Thriving in the Next Era of BaaS

By Alex Johnson

An analogy that I hear a lot in fintech is the Wild West.

Every new thing is the Wild West. Open banking is the Wild West. Embedded finance is the Wild West. Crypto, especially, is the Wild West.

I get the temptation. Technology is a fast-paced, risk-on type of industry. Stuff is moving fast and breaking constantly. There’s opportunity (and danger!) around every corner. The person standing next to you might strike it rich tomorrow and wind up a millionaire. Or they might go broke. Literally everyone is selling picks and shovels.

In general, I don’t find this framing super useful.

(crypto, for instance, has told us explicitly that it’s going to the moon)

The one exception is banking-as-a-service (BaaS).

Whenever I think of BaaS, my mind immediately flashes back to all the time I spent as a kid playing The Oregon Trail. It was just the perfect mix of optimism (move your entire family west in search of a better life), audaciousness (I can totally travel 2,100 miles in a covered wagon on a $1,600 budget), and danger (a thief just stole my oxen?!?).

Just like BaaS (and fintech generally, really)!

It’s also a surprisingly useful analogy. Much like the initial mapping of the Oregon Trail by Lewis and Clark, the subsequent usage of that trail by an estimated 400,000 travelers, and the eventual settlement of the West, I think you can break the evolution of BaaS into three distinct phases:

- Feasibility (how do we get there?)

- Speed (how do we get there faster?)

- Sustainability (how do we thrive once we’re there?)

So … that’s exactly what we will do in today’s essay – analyze the evolutionary history and future of banking-as-a-service!

But first …

A Quick Definition of Banking-as-a-Service

As with everything in fintech, BaaS has become a bit of a loaded term.

So let’s align on a definition.

(a tip of my hat to my friends at Alloy Labs for their help)

Banking-as-a-service is a partnership model in which a financial institution leverages its bank charter to enable one or more non-bank companies to offer financial products directly to consumers.

There are two models of banking-as-a-service: direct and indirect.

In the direct model, the bank supplies the systems and technology required for the fintech company to connect to the bank’s system of record. Some banks may also offer compliance or other advisory services to their fintech partners.

In the indirect model, a third-party platform – like Synctera – supplies the technology and APIs required for non-bank companies to build and launch banking products, with accounts, card issuance, money movement, and lending, all powered by a sponsor bank. These BaaS platforms often also assist fintech companies with forming and managing relationships with sponsor banks.

Make sense?

Great! Now let’s get into the evolution of BaaS, starting at the beginning.

Phase 1: Feasibility (how do we get there?)

The modern banking-as-a-service model emerged from the collision of two different trends, which both started in the 1980s:

- Partner-led Revenue Generation. The development of the Discover card, created by Sears in 1985 to drive more in-store commerce, kicked off a 40-year flurry of non-bank financial product innovation, everything from retail credit cards to indirect auto lending to general-purpose reloadable prepaid cards. Over time, these product areas came to be dominated by a select number of large banks, which developed deep specialization in serving specific non-bank partner segments. These banks, in return, benefited from highly efficient and scalable distribution channels, which generated new, low-cost revenue streams (primarily fees).

- Partner-led Deposit Gathering. In the early 1980s, a new and very potent strategy for deposit growth came to prominence – brokered deposits. The basic idea was that a bank looking for more deposits would create specially-priced deposit products (usually CDs) for brokers (think of companies like Fidelity and Charles Schwab) to sell to their customers. Those customers, typically rich and looking for yield, would sign up en masse, and the bank would see a spike in deposits. This strategy was expensive for banks (they had to pay higher interest rates in order to be attractive to the brokers and their customers), but it was an efficient way to raise a lot of deposits quickly. It was so efficient that in 1989 Congress amended the law to limit banks’ ability to accept brokered deposits, after seeing multiple bank failures resulting from irresponsible lending funded by brokered deposits.

In 2009, these two trends smashed into each other.

That was the year the first generation of neobanks – companies like PerkStreet and Simple – were founded.

Of course, we didn’t call them neobanks back then. That term didn’t exist, and the idea of a start-up providing banking services was pretty weird. It didn’t fit into any of the existing molds. This wasn’t a large, well-known retailer wanting to juice sales by offering a store credit card. It was closer to the “bank account” offered by Walmart, built on top of a general-purpose reloadable prepaid card, but without Walmart’s scale and ability to cross-subsidize.

This was a bank account offered for free by a startup that wasn’t a bank.

So, the question, in 2009, was how do you make that model work?

If you are the Lewis and Clark of BaaS (PerkStreet and Simple), how do you get from St. Louis, Missouri to the Pacific Ocean?

The short answer? You try everything.

You explore every conceivable path forward. You make a list of every bank in the U.S. that needs more deposits and has at least some familiarity with partner-based distribution (particularly prepaid), and you call them, one by one by one. You pitch them on being your sponsor bank. You explain to them, “No, this isn’t like your other prepaid partnerships, where we pay you to hold the deposits for us. There may be some interchange revenue that we can split, but the big value to you are these cheap brokered deposits that we’re bringing you.”

You eventually cross out every bank name but one – The Bancorp.

You build your product and UX on top of The Bancorp’s existing tech stack, including its core system. There are no For Benefit Of (FBO) accounts or shadow ledgers. This is a new thing! You are essentially a new division of the bank, subject to the direct oversight of their compliance and risk management teams, who, like you, are trying to figure out how to build the wagon while driving it. You spend years winning their trust and convincing them to give you a bit more autonomy and control over the onboarding and monitoring of your customers. And later, you find out that the bank got itself into trouble with regulators (who were frantically playing catch up on this new model) for being too lax in managing the risk of its third-party programs:

By 2014, it was one of the biggest players in the prepaid card and payments space. And it was in trouble.

That summer, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. slapped the bank with a consent order over weaknesses in its Bank Secrecy Act and anti-money laundering compliance program. Until it resolved those deficiencies, the bank couldn’t establish “any new prepaid card program or issue any new prepaid card product, or establish any new distribution channel for existing prepaid card products.”

The result is that you discover a passage to the Pacific Ocean … and the process nearly kills you.

(Editor’s note – you could argue that it did kill them, as PerkStreet shut down in 2013, and Simple was acquired by BBVA in 2014. I don’t really buy that, though. Low interest rates and being a bit early to the market were the bigger factors, IMHO.)

Phase 2: Speed (how do we get there faster?)

OK, so now we know that it’s possible to get from Missouri to Oregon.

Next question – how do we speed up that journey? How do we make it faster, easier, and less expensive for non-bank companies to start offering banking products and services?

This is the question that many companies in the financial industry have spent the last ten years working diligently to answer.

The reason for this diligence is easy to understand:

- Persistent low interest rates led investors to look for yield in new places. So …

- Fintech, having demonstrated its ability to create new value for customers, became a popular target for VC investment. So …

- More and more people started fintech companies to capitalize on this funding boom and customer enthusiasm. So …

- The demand for sponsor banks increased significantly. So …

- Small banks, struggling with low margins due to the interest rate environment, enthusiastically jumped into BaaS. So …

- An opportunity emerged for new platforms that can help match up supply and demand in BaaS.

It’s worth taking a minute to talk more about that last point – the rise of BaaS platforms – because it clearly illustrates the incentives that drove this phase of evolution in the banking-as-a-service space.

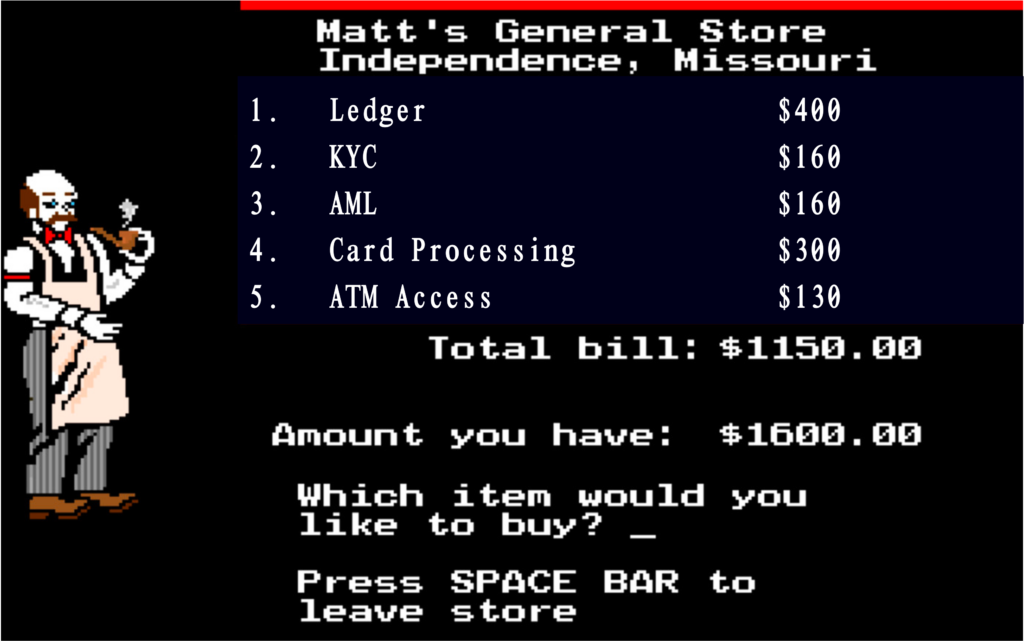

Remember, when the first generation of neobanks were figuring out the feasibility of this model, they were deeply embedded within their sponsor banks. They had to directly connect to the banks’ ancient core systems. The systems used for account opening and KYC and AML and card processing were the systems that the bank chose.

This was not scalable.

But neither was the approach taken by the second generation of neobanks (think companies like Chime and Current). These companies tended to build their own backend technology stacks, including their own ledgers (this was, roughly, when FBO accounts became a popular structure for bank-fintech partnerships). This had the advantage of putting more control in the hands of the fintech companies (your roadmap was no longer subject to the bank’s IT constraints), but it was also a lot of upfront work and expense.

BaaS platforms solved a lot of these challenges.

They provided a set of modern APIs to integrate with rather than forcing non-bank companies to integrate directly with banks’ legacy core systems. They integrated multiple sponsor banks into their platforms, enabling non-bank companies to work with the bank(s) that best fit their needs (and easily leverage multiple sponsor banks, if needed). And finally, the BaaS platforms integrated all the third-party services providers (for tasks like KYC/AML, ATM access, and card production and processing) that their non-bank clients might need.

Put simply, BaaS platforms meaningfully increased the odds that these fintech fortune seekers would make it out to Oregon for the gold rush.

But not every BaaS platform shares the same philosophy for how to help non-bank companies launch bank products and services.

There are two competing visions, which I initially outlined in this newsletter last year. I call them the AWS model and the Hinge model.

The AWS model prioritized building a developer-first platform that focuses on abstracting away as much complexity from the process of launching a financial product as possible. The goal is to make it drop-dead simple, just like spinning up a computing environment with AWS. No need to talk to (or even think about) the sponsor bank on the other end. No need to worry about compliance.

The Hinge model is, essentially, the opposite. The name is in reference to the Hinge dating app, which markets itself as “the dating app designed to be deleted.” BaaS platforms following this model focus on matching up non-bank companies and banks in mutually beneficial partnerships. Rather than abstracting the sponsor banks out of the equation entirely, these platforms focus on helping non-bank companies find sponsor banks that they will love. These platforms streamline the technical and legal processes that go into creating and launching financial products, including, in some cases, providing a modern, unified core system for both their bank and non-bank clients to use. However, BaaS platforms following the Hinge model never prioritize the reduction of technical or operational complexity over the need to keep their non-bank and bank clients in direct control of the relationship.

Phase 3: Sustainability (how do we thrive once we’re there?)

The reason that the AWS/Hinge distinction is important is that it speaks to the animating tension at the center of banking-as-a-service these days – sustainability.

If the last 15 years have been about finding a passage to Oregon and optimizing the trip to get there, the foreseeable future will be about figuring out how to thrive in Oregon, post-arrival.

The reason I feel confident in saying that is that 2022 was a challenging year for lots of companies in the banking-as-a-service space.

On the demand side, the rapid interest rate hikes and the accompanying slowdown in VC funding going into fintech put a damper on the demand for BaaS. There are simply fewer neobanks starting up today than there were three years ago, and the number of banking service providers already in the market is as high as it has ever been.

On the supply side, there are two big issues.

First, like the demand side, there is a large number of market participants. In 2012, Andreessen Horowitz estimates that only six banks were providing BaaS. Today, that number is well over 30, with more jumping in every month. Competition, among BaaS banks, for non-bank partners is fierce.

Second, and more importantly, bank regulators are applying a great deal more scrutiny to banking-as-a-service than they ever have before:

- The biggest development was the consent order reached between the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and Blue Ridge Bank. The OCC ordered Blue Ridge to improve its oversight of third-party fintech partnerships and bolster its AML risk management, suspicious activity reporting, and IT controls after the regulator “found unsafe or unsound practice(s).”

- More broadly, the OCC has significantly ratcheted up its focus on bank-fintech partnerships in recent years. In 2021, it published a guide for community banks conducting due diligence on fintech companies. Last year, Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael J. Hsu expressed concerns about the state of the fintech industry, and in particular banking-as-a-service, saying, “the growth of the fintech industry, of banking-as-a-service (BaaS), and of big tech forays into payments and lending is changing banking, and its risk profile, in profound ways … My strong sense is that this process, if left to its own devices, is likely to accelerate and expand until there is a severe problem or even a crisis.” In 2022, the OCC also announced the creation of the Office of Financial Technology and made it clear that third-party risk management would be a major focus in its 2023 bank supervision plan.

- The Treasury Department also lent its voice to the subject of BaaS regulation in 2022, recommending that bank-fintech partnerships be subject to “enhanced supervision” and encouraging different regulatory agencies to work together to achieve that outcome through a “clear and consistently applied supervisory framework for bank-fintech partnerships.”

Taken together, these headwinds suggest that BaaS banks, fintech companies, and BaaS platforms have a lot of work to do to position banking-as-a-service as an operating model that can thrive over the long run.

I’d like to talk through what some of that work will look like.

Building a Good Rhythm

Walt Cox, Head of Partner Banking at Valley Bank, has a good line on BaaS:

No fintech is worth jeopardizing your charter.

No bank is worth jeopardizing your roadmap.

The art is in between, dancing together hand in hand.

Poetic, right?

And a great articulation of the subtle, inescapable challenge that comes with banks and fintech companies working together.

I think of it as an operating rhythm problem.

Every company has a rhythm and a pace at which it operates. Banks and fintech companies move at very different paces.

This shouldn’t be surprising. Banks and fintech companies have very different incentives.

The incentive for banks is to be careful. Banking is a durably profitable business model, but it depends on trust. Banks are very careful not to damage that trust, and they are subject to many regulations designed to nurture and protect that trust. As such, banks tend to hire diligent, conservative employees who can think about and manage risk holistically, and they usually operate using a command-and-control organizational structure.

By contrast, the incentive for fintech companies (and most tech-first, non-bank companies) is to grow quickly. Generally speaking, speed wins. These companies want to constantly run experiments and iterate constantly. They understand and accept the risks of moving fast. As such, these companies tend to hire innovative, experimental employees who fail and learn fast, and they usually operate using a more decentralized organizational structure that gives the maximum amount of autonomy to engineers.

There is a natural incompatibility here that makes BaaS extremely difficult.

This difficulty will never go away, but there are certain technology and process considerations that non-bank companies should make to ensure the highest likelihood of building thriving, long-term banking-as-a-service partnerships.

In speaking with multiple banking-as-a-service experts, on both the bank and non-bank sides of the aisle, in my research for this essay, here are the ten most important recommendations for what fintech and other non-bank companies can do to ‘sync up’ their operating rhythm with their sponsor banks and increase the odds of profitable and durable relationships.

1.) Invest a lot of time upfront to find the sponsor bank that is the best fit for you.

This process is a lot like fundraising. Potential sponsor banks are going to be evaluating not only your risk profile but your business plan as well. They want to pick winners. So, much like the due diligence you do on potential investors, make sure when you’re vetting out potential sponsor banks that you’re clearly communicating what makes you different.

Check for understanding – does the bank (and BaaS platform, if you are using one) understand what your product vision is and what you’re planning to build? Is it a good fit? Increasingly, banks entering the BaaS market are choosing to specialize in specific areas (high-risk industries, complex product categories, unique geographies). If your product vision is highly specialized, seek out a specialized sponsor bank. It’s worth the extra effort.

And remember to take your time. If a prospective sponsor bank appears to be rushing through their due diligence or not taking the time to understand all the nuances of your business case, that’s a red flag.

2.) Understand what the sponsor bank(s) want to get out of BaaS.

Think deeply about the value that you provide to the bank and the objectives they are trying to achieve. What is their strategic goal for participating in BaaS? Are they trying to generate fee revenue? Is this a deposit acquisition play? (this is a strategic priority for almost every bank these days)

The better you can understand the bank’s goals, the better positioned you’ll be to understand if they’re a good fit for you and (if they are) where your leverage is with them in a negotiation.

3.) Remember that reputation matters.

In BaaS, as in life, your reputation is everything. The best sponsor banks, the ones that have great relationships with their regulators and top-tier fintech partners, are, unsurprisingly, very picky about which additional partners they take on. Work hard for those partnerships.

Partnering with second and third-tier sponsor banks is a much easier task (they take pretty much anyone and do little-to-no due diligence!), but it creates a lot of long-term risks. Remember, their reputation with regulators and the reputations of all the other non-bank companies they partner with also reflect on you.

4.) Establish a compliance program and culture before you launch.

Building on the previous point, no sponsor bank that you would want will be interested in working with you if you consider compliance to be a post-launch activity.

Compliance – everything from documenting policies and procedures to designing a compliance training program – should be done well before you launch and, ideally, before you start talking to potential sponsor banks.

BTW, Synctera has a great blog post on this subject if you want to learn more about this point.

5.) If working through a BaaS platform, insist on a direct relationship with your sponsor bank(s).

Returning to the AWS vs. Hinge question, I strongly urge the Hinge route.

At the end of the day, the bank is responsible for ensuring that every financial product and service offered through its charter is fully compliant with all applicable regulations. A bank will never be able to tell their regulator, “Hey, I’m not sure what’s going on with that; you should check with our BaaS platform provider.” That will never be an acceptable answer.

It’s tempting to pick a BaaS platform that promises to handle all of the annoying bank compliance stuff for you, but this is not a sustainable approach.

6.) Plan for the future (the good).

I see this mistake a lot. A fintech startup will pick a sponsor bank based on their needs today without considering how those needs might evolve as they grow. They don’t ask questions like, “Can this bank support not just my MVP, but my long-term product roadmap?” Or “How quickly might I outgrow this bank’s balance sheet?”

7.) Plan for the future (the bad).

Equally important is planning for the bad stuff. Business continuity and disaster recovery plans aren’t super fun to draw up, but they are absolutely critical for ensuring that you (and your partners) will be able to handle unexpected problems and keep customers’ money safe and accessible, no matter what.

I expect this to be an area of focus for regulators in the near future.

8.) Build in as much flexibility as possible.

Things change (no matter how much planning for the future you do), so try to build in as much flexibility as possible.

It’s important to understand the banking infrastructure you will be building your product on top of. Can you switch sponsor banks or add another sponsor bank easily? Can you swap in different third-party service providers without incurring huge costs? Is your product roadmap constrained by your sponsor bank’s core? Can you launch new product structures quickly?

9.) Be able to manage data like a bank, not a tech company.

Ensuring a smooth and productive relationship with your sponsor bank requires, first and foremost, giving them all the information that they need to monitor your performance and answer the questions that their regulators are going to ask them.

Make sure that your systems, such as your ledger, are set up to easily track customer and transaction information the way that a bank would. For example, many fintech companies don’t think about the necessity of double-entry accounting, which allows you to understand how money is coming into your customers’ accounts and where it is going. Having a clear view into both sides of each transaction gives you a complete view of your customers’ data, helping you better identify fraud and signal to regulators that you can accurately keep track of the flow of funds for your product.

10.) Overcommunicate. Overcommunicate. Overcommunicate.

All the APIs and automated monitoring and machine learning algorithms in the world can’t substitute for effective personal communication between the key stakeholders within your organization and your sponsor bank.

Are you setting the right expectations? Are you effectively conveying your strategic priorities and product roadmap and giving them adequate time to review and provide feedback? Are you doing what you can to streamline any required reviews or audits that they are going through?

A New Environment

In a low-rate, light-regulatory-touch environment, it’s almost impossible not to look like a genius.

This is the environment that modern banking-as-a-service grew up in.

It was like being able to set your pace in The Oregon Trail to “grueling” but without any of the broken wheels or lame oxen.

The problem with that environment was there wasn’t much incentive to do things the right way or to think long-term. You just bought your wagon, loaded up your stuff, and set off to Oregon.

We don’t have that problem anymore.

Non-bank companies looking to offer banking products today have every incentive to build a sustainable roadmap, and I’m quite sure we’ll see those incentives shape the next phase of evolution in banking-as-a-service.

About Sponsored Deep Dives

Sponsored Deep Dives are essays sponsored by a very-carefully-curated list of companies (selected by me), in which I write about topics of mutual interest to me, the sponsoring company, and (most importantly) you, the audience. If you have any questions or feedback on these sponsored deep dives, please DM me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Today’s Sponsored Deep Dive was brought to you by Synctera.

About Synctera

Synctera is powering the future of FinTech for companies that want to create new revenue streams and enhance their value proposition by offering FinTech apps and embedded banking products. With APIs, compliance support, and sponsor bank partners in one end-to-end Banking as a Service platform, Synctera is the fastest and easiest way to build, launch, and scale bank accounts, debit cards, charge cards, lending, and more.