17 March 2023 | FinTech

Could BaaS Prevent The Next SVB?

By Alex Johnson

The conversation around SVB – which I have found to be both exhausting and enlightening, in very unequal measures – has shifted from diagnosing what happened to prescribing what should happen next in order to prevent more Twitter-fueled bank runs.

These prescriptions range from absurd (bitcoin does not fix this, and a de-evolution away from fractional reserve banking would cause more problems than it would solve) to mundane (re-lowering the asset threshold to $50 billion for more stringent stress testing and capital requirements seems like a reasonable idea to discuss).

I have a different idea in mind, which I think falls somewhere in between these two extremes.

In order to explain it, I first want to briefly revisit what Silicon Valley Bank was really good at and what it was really bad at, and why those two things were highly correlated with each other.

SVB (The Bank)

A while back, I wrote about the challenge that most banks have in lending money to small businesses. The core premise of the essay was that small businesses usually look like bad credit risks because starting a small business is, objectively, a crazy thing to do. Most fail, and predicting the ones that will succeed is, especially early on, usually more of an art than a science. In the article, I made the case for a necessary, often overlooked ingredient in effective small business lending:

What’s needed, to bridge this gap, is understanding; the ability to analyze the available data (requested loan amount, cashflow, business history, collateral) within the context of the business opportunity that the entrepreneur is so passionately pursuing.

I was reminded of this when I was reading up this week about the success that SVB had in growing into the 16th largest bank in the U.S. by almost exclusively focusing on the needs of tech startups and venture capital firms.

(Editor’s note: fair warning. You may need to hold your nose for parts of this next section, in which I will be featuring a few quotes from startup founders about the problems that SVB solved for them and the perks that they received from working with SVB.)

As the New York Times notes, tech startups are a particularly weird type of small business:

For 40 years, the institution catered to the fact that high-growth, high-risk tech start-ups and their backers do not adhere to normal business practices. These companies put a priority on breakneck growth, shift strategies frequently and celebrate failure as a learning opportunity. They are often worth billions before ever turning a profit, and they can go from silly idea to behemoth at astonishing speed. Most crucially, they rely on a tight network of money, workers, founders and service providers to function.

That unique and often irrational reality required a specialized bank.

SVB was that specialized bank, and at the root of its specialization was a deep understanding of the tech startup ecosystem works, as this quote from a recent Wired article illustrates:

“They understand our innovation ecosystem and build all of their offerings around that,” says Hemant Taneja, the chief executive and managing director of General Catalyst, a venture capital firm that banks with SVB. “They have the trust of the VC community that they will help these companies through thick and thin.”

The offerings that were built around that understanding covered both the practical needs of startups and their founders, such as frequent international wire transfers:

[Vai] Gupta, the real estate entrepreneur, is already missing SVB. He wires money internationally at least a couple of times a month for his startup BonfireDAO, which aims to lower barriers to buying properties using blockchain technology that underpins cryptocurrencies. He estimates that Chase, his new bank, will charge him $5,000 a year for the transfers, which SVB provided for free.

Venture debt:

the ease of borrowing money from SVB has been the biggest draw for many companies. Startups take out bank loans to diversify their financing, and they often can secure the dollars without giving up as many shares as they have to provide venture investors.

Zefr’s [Zach] James has taken out loans for his company several times through SVB after shopping around. In some cases, the bank takes a small ownership stake in the borrowers. Other times it defers principal payments for a year or two or allows for repayment in a single lump sum. “It was the catch-all for startups,” James says of SVB.

Generally, it offered among the least-restrictive terms and equally competitive interest rates, entrepreneurs say. If a borrower failed, SVB was known to handle it more gracefully than other lenders. Effectively, according to language seen by WIRED, SVB would support companies as long as their venture capital backers, often clients of the bank, did not abandon them. “Bankers become a lifeline when you get into trouble, and if they stand by you, I take that seriously,” says James of his loyalty to the now crushed bank.

And mortgages:

One [Y Combinator alumnus] described a cocktail hour mixer in which he was introduced to an SVB banker who could provide a loan to his start-up once he graduated from Y Combinator’s program. Six months later, when he needed a loan to buy his first home, he went to SVB. The bank looked at his company’s valuation, based on the money it had raised in its first round of funding, and spoke to investors of his company. It granted a loan after two other banks turned him down, he said.

SVB’s home loans were significantly better than those from traditional banks, four people who received them said. The loans were $2.5 million to $6 million, with interest rates under 2.6 percent. Other banks had turned them down or, when given quotes for interest rates, offered over 3 percent, the people said.

As well as the perquisites:

SVB also offered customers freebies through a dedicated section in its mobile app long before other banks dangled similar discounts to startups, says Gupta, who from SVB has taken advantage of Amazon Web Services cloud computing credits and free DocuSign e-signature services. He attended over a dozen SVB events, including sessions on finding cofounders and pitching investors. The bank would also let him stop by for a free lunch or to use a meeting room during business trips. “They were very hospitable,” Gupta says. He says he might now have to shell out for a WeWork membership.

Entrepreneur Adam Zbar has enjoyed the use of an SVB ski house with a dock on California’s Lake Tahoe. As CEO of meal delivery company Sunbasket, he would use it to host weeklong retreats for his management team. The bank would bring in a top chef for a night and exclusive wines from SVB’s winery clients. “It was phenomenal,” Zbar says.

SVB sponsorships also helped pay for trips for Los Angeles tech entrepreneurs to ski at Mammoth Mountain in California and surf at a human-made ranch constructed amid farms, says Zach James, co-CEO of ad tech company Zefr. SVB would take clients to race fancy cars, go backstage at music festivals, and meet vintners at private sessions at Napa Valley wineries to the point that it hosted 300 wine-related events one year.

And it wasn’t just startups and their founders. SVB built very strong relationships with the venture capital firms (and their partners) that backed their startup customers, offering everything from bank accounts to investments in the VC firms’ own funds and portfolio companies:

Drive Capital, a venture firm in Columbus, Ohio, banked with SVB and had lines of credit with the bank that allowed it to wire money to its start-ups faster than asking its own backers to send the money for each individual deal. SVB also invested in Drive Capital’s first fund and in two of its portfolio companies. In total, a third of Drive Capital’s portfolio used SVB’s banking services, which included venture debt, a specialized kind of credit for venture-backed start-ups.

It was even financing renovations to VC firms’ offices:

When Kleiner Perkins, one of Silicon Valley’s highest-profile venture capital firms, wanted to build a bridge between two of its office buildings around 2005, it decided to take out a loan. It turned to Silicon Valley Bank, just 43 feet away on Sand Hill Road in the heart of the venture industry in Menlo Park, Calif.

To make the loan work for Kleiner’s project, which cost more than $500,000, SVB agreed to lend the money against the value of the fees that the venture firm was set to earn from its funds, four people with knowledge of the situation said.

In very simple terms, SVB’s playbook over the last 40 years can be boiled down to:

- Build relationships with the customers you want to serve and work to understand their unique financial needs.

- Leverage your unique understanding of those customers to build tailored products for them and make you comfortable taking risks to serve them that others would be uncomfortable with.

- Reinvest your profits in strengthening your relationships with your customers.

The key to this strategy is focus. You make a big bet on your ability to serve a specific customer segment better than anyone. And when that bet pays off, you double down on it. And then you double down on it again. And again.

In the context of this strategy, diversification is rightly viewed as a distraction. If you look at the 40-year history of SVB, you will find very few attempts at diversification. And the ones you do find, like its expansion into the wine industry in the 1990s, have more relevance to its core market than you might think:

SVB also branched out to industries adjacent to tech, such as the wineries of Napa and Sonoma Valleys, where many tech founders and executives spend their weekends. Last year, the bank lent $1.2 billion to wine producers.

Gavin Newsom, California’s governor, who praised SVB’s bailout last week, has received loans for three of his wineries from SVB, according to the bank’s website.

This was a very smart growth strategy, but it was a very dumb risk management strategy.

SVB (The Balance Sheet)

The actual cause of SVB’s failure was an asset-liability mismatch that became untenable due to faster-than-anticipated deposit outflows (if you want to dig into the gruesome details, check out last week’s essay).

The proximate cause of SVB’s failure, I would argue, was specialization.

Everything that made SVB (the bank) successful came back to its obsessive focus on the tech startup ecosystem. Its goal was to be, by far, the most convenient and enjoyable place for a founder to bank. If you kept your deposits there, you could get free international wires, non-dilutive venture debt financing, and even personal loans based on your equity (and your VC investors’ commitment to that equity). As a result, tech startups loved banking with SVB, and SVB acquired and retained a dominant share of the tech startup banking market.

This obsessive focus also wrecked SVB (the balance sheet).

Because SVB wasn’t in the business of saying no to startups, it took in a massive amount of deposits (liabilities) between 2019 and 2021 as funding in tech startups swelled due to low interest rates. And because startups don’t have the same need for traditional lending products that your average SMB does, SVB had limited options for deploying those deposits to generate a return, which led to it reaching for too much yield on long-term, fixed-rate securities. Matt Levine summed this up well:

the basic story of the fall of SVB is that venture-backed tech startups plowed too much money into SVB too quickly in the boom times, and took it out too quickly last week. SVB had nowhere to put that money except in long-dated government bonds with lots of interest-rate risk; when rates went up those bonds lost money, and when its depositors all fled last week it realized those losses and went bust. The depositors were the problem.

For SVB (the bank), the depositors were the key to success. For SVB (the balance sheet), the depositors were the problem that doomed them.

This is an odd but apparently inescapable contradiction.

A Quick Side Note on SVB’s Lending Portfolio

As mentioned above, SVB didn’t ever do a ton of lending, and the lending that it did do was mostly weird, bespoke stuff that was tailored to the unique needs of VCs and VC-backed startups.

What’s interesting to me about these loans, which added up to roughly $74 billion at the end of 2022, is that while they are indeed quite weird, they also appear to be fairly safe. Much like the securities portfolio that sank them, SVB’s lending portfolio appears to be solid. I mention this only to reinforce that this asset-liability mismatch problem that we’re experiencing today is fundamentally different than the badly-priced asset problem we were dealing with in 2008.

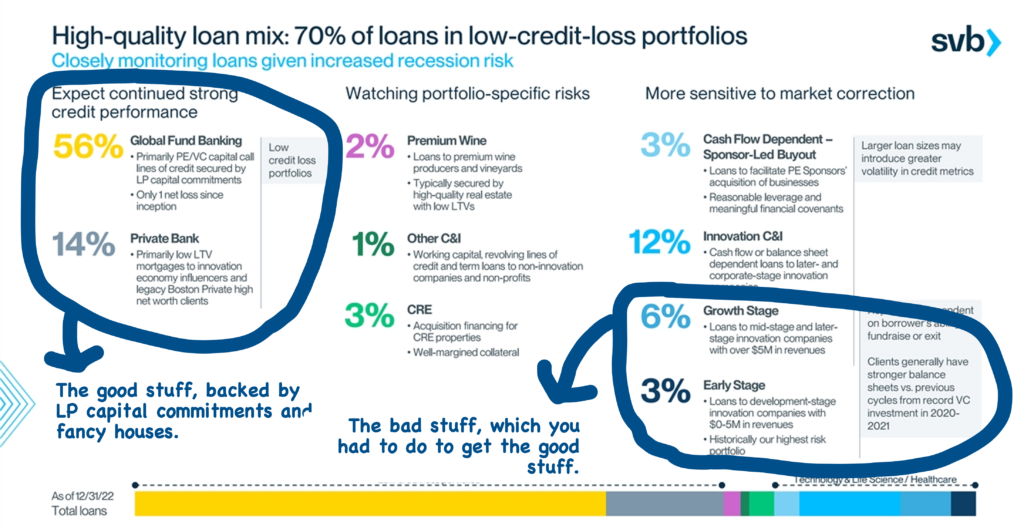

Here’s a snapshot of the SVB loan book from its mid-quarter update last week (with my helpful annotations scribbled on top):

The other interesting thing about these loans, as Todd Baker explained well on Twitter, is that they’re difficult assets to sell to other banks. Every bank would want the 70% of loans to PE/VC firms (backed by LP capital commitments) and mortgages to “innovation economy influencers” (backed by, I presume, really expensive houses). However, as a bank, you only earn the right to make those loans by also making the 9% of loans to tech startups, where repayment is dependent on additional fundraises or an exit.

Building this interconnected book of lending businesses was a natural byproduct of SVB’s customer-focused growth playbook. It’s also one of the reasons that the FDIC is having a hard time finding a buyer for SVB.

Do We Need Large Regional Banks?

In the aftermath of SVB, one big concern is how its failure might affect other large regional banks, banks that are big enough to destabilize confidence in the U.S. banking system if they were to fail but small enough to fall below the threshold of being a systemically important financial institution (SIFI), which is a designation that comes with far more extensive capital requirements and stress testing.

(Editor’s note – as I referenced above, the line for where we consider U.S. banks to meet this SIFI designation has changed over the years. We used to have it at $50 billion in assets, but it was raised in 2018 to $250 billion.)

This concern has motivated the market to move against the stocks of many of these large regional banks this week, with First Republic being an especially notable example:

First Republic’s stock, which closed at $115 per share on March 8, traded below $20 at one point Thursday. The stock was halted repeatedly during the session and rose nearly 10% on the day, closing at $34.27 per share.

In response (and apparently with encouragement from federal regulators), a group of the largest banks in the U.S. (including our big four SIFIs) agreed to deposit $30 billion into First Republic in a show of support and confidence, as their statement on the move says:

“This action by America’s largest banks reflects their confidence in First Republic and in banks of all sizes, and it demonstrates their overall commitment to helping banks serve their customers and communities,” the group said in a statement.

Banks of all sizes.

That’s the key phrase. And it’s interesting, especially coming from the largest banks in the country, which all got to where they are by gobbling up their smaller rivals.

It provokes an important philosophical question – how many banks should we have in the U.S.?

Matthew Yglesias, the writer of the Slow Boring newsletter, had an interesting take:

banks operating on the scale of Silicon Valley Bank — the so-called large regional banks — are bad, and the policy of the United States government should be to encourage regional banks to merge and become megabanks comparable in scale to the Big Four. Megabanks are better-regulated and less risky than large regional banks, and creating more of them would lead to a more competitive megabank marketplace and eliminate some of the problems of concentration.

His argument (which you should read the entirety of) can be boiled down to three main points.

First, he correctly points out that most small bank failures are handled successfully and with minimal drama by the FDIC:

In this situation, the purchasing bank typically pays $0 for the failed bank and in exchange receives the failed bank’s branches, whatever investment assets are left on its book, and the failed bank’s clients and client relationships. The purchasing bank is also now obliged to give depositors their money if they ask for it. This means insured deposits are taken care of without the FDIC spending its money and uninsured deposits are also taken care of without the FDIC spending its money —a good deal for everyone involved. But it relies on the idea that when a small bank fails, another bank will want to take over its branch network.

This is basically a numbers game. There are a lot of banks in the United States, and since “buying” a failed bank is essentially free, the bet is just that some bank or other will have an executive team that’s ambitious enough to want to expand.

The main issue the FDIC deals with in practice is that it tries to avoid excessive geographic concentration. So if a bank with seven branches fails, the preference is to sell it to a bank that doesn’t currently have branches in those communities to preserve local competition. But sometimes that isn’t possible, and the bank that’s most interested in buying has an anti-competitive motive.

In practice, though, this process basically always works out.

Second, he posits that the problem with mid-size banks is that this market-led solution is a lot more challenging:

The problem is, what happens if PNC fails? PNC is the sixth largest bank in the country with over $500 billion in assets. That makes it dramatically smaller than the Big Four banks that are informally labeled “too big to fail” and formally classified as Global Systemically Important Banks (GSIBs).

But PNC is still big enough that almost none of the thousands of banks in America could buy it in the event of a failure. And even if Chase or Bank of America could swallow PNC, it’s not clear that they would want to. PNC has an expansive branch network, so expansive that it’s largely duplicative of the network of any possible purchaser.

And finally, he argues that the only way to resolve this tension between enabling large regional banks to compete and maintaining confidence in the U.S. banking system is to allow (and even encourage) large regional banks to become a whole lot bigger:

Giving the regional banks a lighter regulatory touch lets them operate higher-margin businesses, which lets them invest in superior customer service, which is how a lot of business owners end up preferring to bank with them rather than with a GSIB. Take away the favored regulatory status and those banks will have a harder time.

I think the solution is to drop the regulatory skepticism of bank mergers.

And this is where he loses me.

The solution for creating a more competitive banking ecosystem isn’t to allow PNC to M&A its way into becoming a slightly crappier version of JPMorgan Chase (we already have Wells Fargo). And the solution, clearly, is not to reduce the regulatory burden on large regional banks (we just tried that).

The solution is to create an environment in which financial services providers like SVB (the bank) can flourish without creating narrow, brittle balance sheets on the backend of those entities.

And I think we have a structure already in place (in a pupal form), which could offer an interesting blueprint.

A New Choice for Large Regional Banks

Allow me to sketch out a vision of the future, which I will admit is both very rough in its details and highly unlikely to actually come to fruition.

What If Every Large Regional Bank Was Either a Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) Bank or a SIFI?

Imagine a parallel world in which every large regional bank, say those over $50 billion in assets, was either a SIFI, subject to the same regulatory oversight as the biggest banks, or a BaaS bank with no customer-facing businesses, just a robust, diversified balance sheet supporting a large number of front-end fintech partners.

I think this would, theoretically, address a few different problems:

- It would give financial services companies more of an incentive to focus on their core competencies. If you’re great at honing in on a specific customer segment, designing products that meet their unique needs, and building a world-class brand within that customer segment (as many fintech companies are), focus on doing that! Don’t worry about asset-liability mismatches! If you’re great at risk management and building a banking balance sheet that is resilient across different interest rate environments and phases of the credit cycle (as many banks are), then focus on doing that! Leave the annoying customer and product stuff to others. SVB’s problem, in this construction, was that it was a fintech company cosplaying as a bank.

- It would provide greater regulatory oversight on companies that feel confident in their ability to pat their head and rub their stomach at the same time. If you want to do both, if you want to build a full-service, end-to-end bank that can compete with JPMC, then go ahead and give it a try. But we’re going to watch you closely and not just assume that you have it all under control.

- It would create a more robust and competitive BaaS ecosystem. I think that many of the challenges in banking-as-a-service today might be solved if we had more large banks participating in the space. Larger banks have better, more modern technology stacks. They have more resources to dedicate to both compliance and business development. They have larger balance sheets, which allow for a much wider range of supported financial services at a much larger scale. Small banks have had a de facto monopoly on BaaS thus far. It would be interesting to see what fintech companies could build on top of a more robust and competitive BaaS ecosystem.

There are also a few reasons why I think that this parallel world is closer to being a reality for us than you might think:

- Large regional banks are already beginning to embrace the vertical-focused, tech-enabled growth playbook. They would never admit it, but I wonder if the CEOs of large regional banks have come to the conclusion that they will never be able to compete, head-to-head, with the megabanks. With the slow death of branch-based distribution, all banks need to compete on a combination of digital experience, product innovation, and pricing. None of those factors favor large regional banks over megabanks, which is one of the reasons why I think we’re seeing more large regional banks invest in and/or acquire vertical-focused fintech companies. A good example of this is the arms race currently taking place between Fifth Third and KeyBank to acquire the necessary fintech pieces to dominate the healthcare vertical.

- Fintech companies are ready to help large regional banks diversify their balance sheets. B2C and B2B fintech companies have been very successful, over the last 10 years, at building efficient customer acquisition engines. Where they struggle is finding productive ways to manage and monetize the resulting assets and liabilities. Large regional banks could help them with this. Max Levchin, CEO of Affirm, recently tweeted, “a reason why regional banks are vulnerable to asset/liability duration risk is no access to short-term, controllable-credit, higher-yield assets: very few issue credit cards. If only there were quality assets from a responsible lender with consistent, strong credit performance…”

- Fintech companies are starting to work with larger BaaS banks. The dominance of sub-$10 billion asset banks in BaaS is the direct result of the Durbin Amendment’s debit interchange cap exemption for these banks. Neobanks like that revenue; however, I believe that we are (finally) transitioning out of the era in which debit interchange-only business models for neobanks and other fintech companies are an acceptable answer to the question, “how are you going to make money?” As such, I expect that we will see more fintech companies choose to work with larger BaaS partner banks, whose lack of Durbin-exempt interchange will be more than made up for by their ability to support a wider range of products and services and their willingness to scale up without worrying about growing too fast or beyond an arbitrary asset cap. Indeed, we already are seeing this, as neobank HMBradley recently demonstrated by moving from its old partner bank, Hatch Bank ($177 million in assets), to its new partner bank, New York Community Bank (a division of Flagstar Bank, $90 billion in assets). New York Community Bank seems delighted by the opportunity, as its deputy chief digital and banking-as-a-service officer told American Banker, “banking as a service is a way to diversify the way we add deposits onto our balance sheet. It also gives us a front-row seat at some great technology minds that know how to deliver financial service products to their customer bases.”

OK! Maybe this (or something like this) is feasible!

However, there are also a number of problems standing in the way.

The most immediate of these problems is the infrastructure that we are currently relying on to facilitate banking-as-a-service.

Needed: A More Robust BaaS Infrastructure

What happens if a fintech company fails, but the BaaS partner bank behind the fintech company doesn’t?

It shouldn’t be a problem. The bank holding the end customers’ money is still intact. The money is still there!

The challenge is quickly and accurately figuring out who the money belongs to, as Patrick McKenzie, the author of the Bits About Money newsletter, explains:

Many fintech products have an account structure which looks something like this sketch: a financial technology company has one or several banking relationships. It has many customers, enterprises which use it for e.g. payment services or custodying money. Those services are not formally bank accounts, but they perform a lot of feels-quite-bankish-if-you-squint to the people who rely on them to feed their families. The actual banking services are provided to those users by the banks, who are disclosed prominently on the bottom of the page and in the Terms and Conditions.

Each enterprise has their own book of users, who might number in the hundreds of thousands or millions, in a single FBO account at the bank, titled in the name of the enterprise or the name of the fintech. The true owners of the funds are known to the bank to be available in the ledgers of the fintech but the bank may have sharply limited understanding of them in real-time.

And so I ask you a rhetorical question: is this structure robust against the failure of a bank handled other-than-cleanly, such that, come the following Monday, those users receive the insurance protection which they are afforded by law? Mechanically, can that actually be done? Is our society prepared to figure that out over a weekend?

The ledgers that keep track of customers within these FBO accounts are, to put it mildly, not uniformly reliable. Some were built by the fintech companies directly. Some are provided by the BaaS partner banks (many of whom are operating on old core systems). Some are provided by third-party BaaS platforms like Unit and Treasury Prime. Fintech companies will often switch from one ledger to another or even maintain multiple systems at multiple partner banks. For example, as part of its move to New York Community Bank, HMBradley purchased a new core banking system from Thought Machine, which will allow it to maintain a real-time ledger rather than the batch-based one that it was using through Hatch Bank.

This patchwork of modern and legacy systems, which today sits largely outside the purview of banking regulators, is not acceptable, and it certainly will not be sufficient to support the significantly larger and more competitive banking-as-a-service ecosystem that I think we need.

The Lesson of SVB …

… is nuanced.

That’s why it hasn’t fit well into the otherwise-sane-and-totally-respectful discourse that we all have with each other on Twitter.

The things that made SVB great were also, in many cases, the seeds of its eventual destruction. Preventing other large regional banks from suffering the same fate as SVB is a worthy goal, but it’s one that should be approached from a place of appreciation for the good that SVB achieved over the last 40 years.