I’m happy to present the first Hospitalogy guest post from Dr. Benjamin Schwartz, who recently began writing his newsletter Dem Dry Bones which pontificates on healthcare and health tech from a physician perspective. Drop a subscription over there!

I’ve also added in a few interesting subscriber perspectives on the physician-owned hospital debate at the end of this post.

This post first appeared on Dem Dry Bones on March 5, 2023. Read the original here: https://dembones.substack.com/p/physician-owned-hospitals

Physician Owned Hospitals – Are doctors getting POHwned by regulators?

Physician-owned hospitals (POHs) — love ‘em or hate ‘em, the concept sparks intense debate. POHs have always been a favorite topic of mine, and I was intrigued to read Blake Madden’s recent “Hospitalogy” article detailing the pros and cons of POHs. Blake’s insightful (inciteful?) piece inspired me to write this companion piece expanding on some of his ideas and presenting the physician viewpoint. The POH concept is simple, instead of a hospital being owned and operated by corporations, health systems, “non-profit” entities, PE firms, and/or the government, doctors are in charge. The idea makes some sense in that, in theory, doctors best understand the practice of medicine and how treatment should be administered.

The author standing in front of Boston Medical Center (not Venice, Italy) circa 2006 after a pipe burst and the street flooded.

Of course, running a hospital is more than just the clinical nuts and bolts. Properly managing a hospital requires business sense, operations expertise, deep understanding of rules and regulations, and myriad other non-medical considerations. Doctors, who get little financial or healthcare operations training in medical school, are often viewed as being bad at business — so much so that one might view POHs as destined to fail. However, it’s worth pointing out that HCA, the Mayo Clinic, Kaiser Permanente, and other large, dominant health systems had physicians on their founding teams. The bigger concern, as it turns out, is that doctors will be a little too good at the business of hospital ownership — driving up costs, restricting access, and placing too much emphasis on financial considerations.

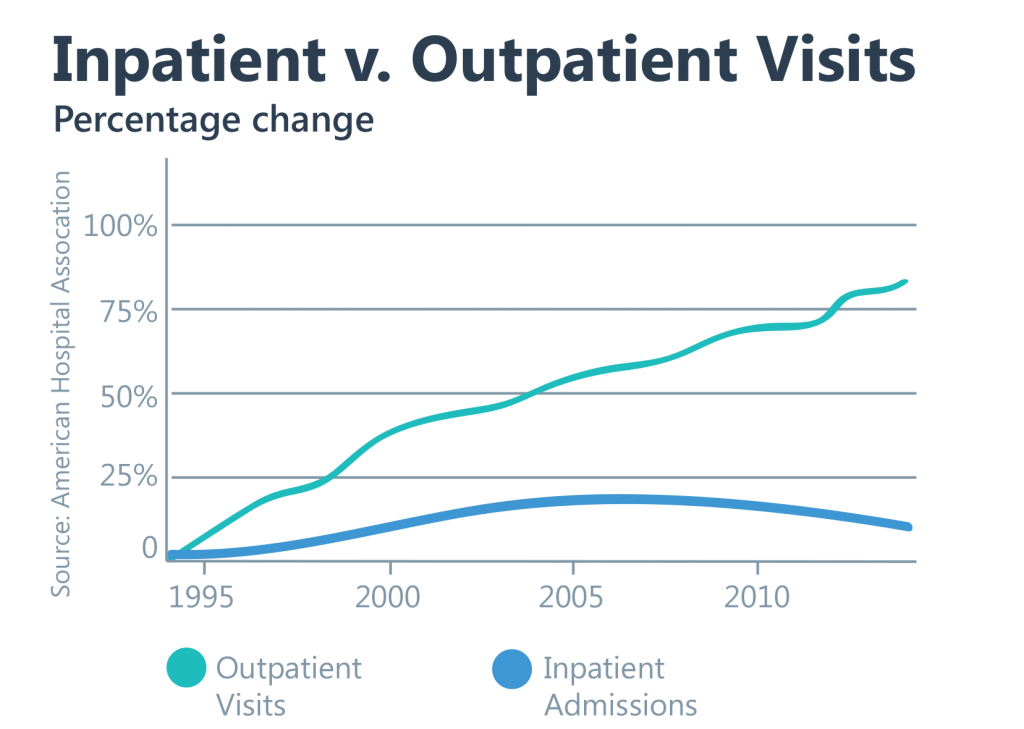

POHs are not a new concept having been around since the 1980s. As Blake points out, renewed interest in physician ownership of hospitals is being driven by a bill that would repeal the 2010 POH ban put into place by the PPACA. The ban aimed to address concerns of physician self-referrals and conflicts of interest leading to overutilization of care based driven by perverse financial incentives (Sound familiar? This is the same argument that frames the FFS v. VBC debate). Self-referrals are limited under Stark Laws. Prior to the ACA ban, physician ownership of hospitals was permitted under the “whole hospital” exemption meaning that physicians had to be on the hook for all aspects of the hospital’s financial performance. Although this exemption no longer exists, Stark Law rules allow for physician ownership of physical therapy, DME, imaging, and ambulatory surgery centers (provided certain conditions are met). This begs the question of whether a repeal of the POH ban is even necessary as more care shifts to the outpatient setting. However, it’s curious that you could just about cobble together the components of a POH as it now stands.

No, this is not a graph of growth in the number of hospital admins v. doctors.

Adding to concerns, POHs have been accused of cherry-picking healthy, well-insured (commercial) patients and lemon-dropping sicker, less insured (Medicare/Medicaid) patients. Hospitals and health systems argue that POHs siphon off the former (read: lucrative) patients while leaving them responsible for the latter (read: money-losing) patients. Such a setup, they claim, threatens their financial viability and the critical healthcare access they provide communities.

A few points and counterpoints here. First, while Medicare and Medicaid patients may not be money-makers for hospitals, health systems have been accused of simply shift the cost of taking care of these patients onto commercially insured individuals. (Though whether cost-shifting is as widespread or pervasive as some think is a matter of debate). Secondly, hospitals and health systems are not immune from de-prioritizing publicly insured patients in favor of the privately insured. Along similar lines, it has been said that being “non-profit” is less of a mandate and more of a tax status. As discussed in a recent episode of the (highly recommended) “Relentless Health Value” podcast, many hospitals and health systems that benefit greatly from non-profit status do the least to give back to the community. Can you claim to be at a financial disadvantage from delivering charity care if the charity care you deliver doesn’t exceed the significant tax benefit you receive?

You might say, two wrongs don’t make a right. I agree. If the ban on POHs is going to be reversed, mechanisms should be put into place that ensure access to all. If POHs claim the care they give is as good or better than traditional hospitals, then all patients should benefit from that care. As part of a repeal, regulators could design mechanisms to ensure cherry-picking and lemon-dropping are kept to a minimum. For example, then Massachusetts AG Maura Healey required the newly formed Beth Israel Lahey Health System to commit to certain measures expanding access to low-income patients and strengthening safety nets as a condition of the merger. The expected shift toward VBC (if it ever happens) could dovetail nicely with the reintroduction of POHs.

To assuage fears of patient selection, both state governments and CMS could engage physician-owned hospitals in VBC arrangements that allow POHs to prove their value proposition (better care at lower cost) while designing programs that make care of public-insured patients more financially attractive. As a final note, a 2015 BMJ analysis of 219 POHs and 1967 non-POHs found that, “although POHs may treat slightly healthier patients, they do not seem to systematically select more profitable or less disadvantaged patients or to provide lower value care”.

“Although POHs may treat slightly healthier patients, they do not seem to systematically select more profitable or less disadvantaged patients or to provide lower value care.”

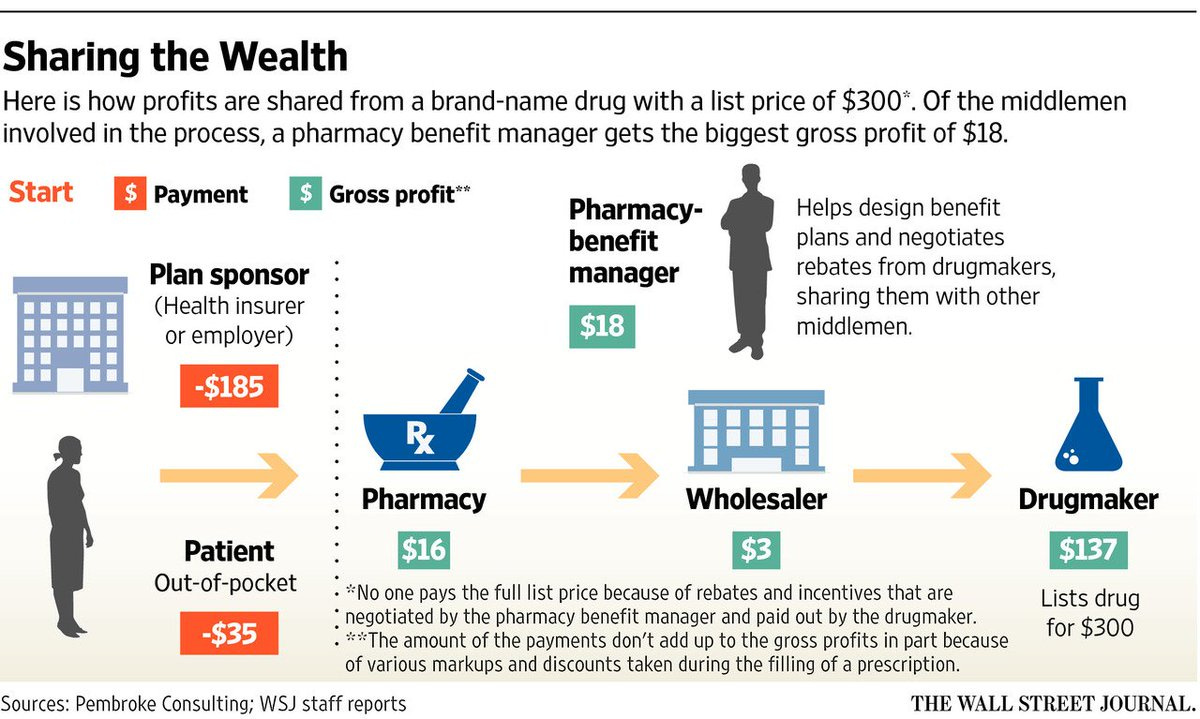

While the above concerns are legitimate, it’s curious that regulators have singled out POHs while looking the other way when it comes to other potentially suspect healthcare arrangements. Hospital and health system consolidation continues largely unchecked. A recent JAMA study from Harvard and the National Bureau of Economic Research found that consolidated care costs more without the benefit of improved outcomes. A subsidiary of a health insurance payor is now the largest employer of physicians in the US. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) have become one of the biggest profit centers for payors and drivers of increased healthcare costs. Even though I hold a couple advanced degrees and have listened to numerous explanations of what a PBM is, I couldn’t tell you what they actually do other than serve as middlemen and drive up costs.

Clear as mud.

Finally, Medicare Advantage (MA) — purportedly a form of VBC — has proven to be mostly an advantage for payors who manipulate risk-adjusted payments to reap significant profits. MA plans have been accused of their own form of cherry-picking and lemon-dropping by reverting patients who become too sick and expensive back to traditional Medicare. Up to this point, little has been done to curb these practices (thought the party may be over soon as the government may have finally caught on). The point here is that, of all the areas of fraud, abuse, and perverse incentives in healthcare, the government has chosen to take strong action against POHs while largely permitting other examples. Entirely banning physician ownership of hospitals over access and self-referral concerns doesn’t square with existing arrangements the government seems more than willing to accept or regulate. Again, two wrongs don’t make a right — but are POHs anywhere near as wrong as the above examples?

Join the thousands of healthcare professionals who read Hospitalogy

Subscribe to get expert analysis on healthcare M&A, strategy, finance, and markets.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

The debate over POHs satisfies Schwartz’s Law of the Medical Literature: for each study showing one outcome, there is an equal showing the opposite outcome. There is good evidence that POHs reduce the cost of care while delivering excellent outcomes and high satisfaction. There is also evidence that POHs increase the cost of care and concerns of overutilization are justified. Like many things in healthcare, your point of view and the evidence you choose to believe is heavily influenced by which site of the debate you stand on (and what you stand to lose or gain). Not surprisingly, the American Hospital Association is very much against the idea of repealing the POH ban for many of the reasons discussed above. (One wonders if they would be against repealing not-for-profit status for hospitals who fail to meet their charitable obligations). Equally non-shocking, the Physician Hospitals of America (PHA) group touts results from the 2015 CMS Value-Based Purchasing program showing that 7 out of 10 hospitals receiving bonus payments were POHs (h/t once again to Blake/Hospitalogy).

“Schwartz’s Law: For every healthcare study showing one outcome, there is an equal study showing the opposite outcome.”

If it wasn’t already obvious, I’m pro-POH. (Of course, I’m squarely on the physician side of the debate). The healthcare environment is different than it was 13 years ago when the ACA ban was put into place. Healthcare costs have continued to rise, and consolidation has further warped market dynamics for the worse. Many are looking to VBC, hospital-at-home, prevention/wellness, digital health, Big Retail/Big Tech, RPM/RTM, and ASCs as the future of medicine. In short, one can envision a future where care shifts away from traditional general hospitals and large health systems (though that isn’t stopping them from pouring money into expensive expansions). To be sure, such full-service facilities will always be needed for treatment of complex patients who require multi-disciplinary treatment and the highest level of acute care. However, turning the healthcare cruise ship around is likely going to require keeping as many patients out of that setting as possible. As hinted at previously, a repeal of the POH ban may not even be necessary if the outpatient migration continues. I’m curious about expanding the microhospital concept to small, specialized centers that excel at doing one or a few things really well rather than trying to be an expensive jack-of-all-trades. Better yet, allowing health systems and physicians to compete on the microhospital level allows market forces to take affect — ostensibly driving down costs and improving outcomes.

Whichever side of the debate you fall on, it’s hard to ignore healthcare’s rapidly developing competition problem. As is usually the case, silos, protectionism, and self-interest rule the day with patients caught in the middle. There’s always the possibility repealing the POH ban would worsen the situation. But a lot has changed since 2010, and the time has come to give POHs another shot.

Quick Takes on Repealing the POH Ban

Given the current state of healthcare costs and quality, one would think every and all options should be on the table. Repealing the POH ban could be a failed experiment in realizing healthcare value or could be the catalyst that helps make VBC a more viable concept. Some other considerations:

- POHs could help reverse the exodus of healthcare workers and reduce burnout by restoring physician autonomy and offsetting downward pressure on professional fee reimbursement. Physicians are gradually losing their seat at the table. One solution: build your own table.

- Beyond the concept of a physician-owned hospital, maybe we should consider a “Clinician-Owned Hospital (COH).” Nothing galvanizes or gives purpose more than a sense of ownership and personal responsibility. If physicians can have ownership, why not nurses, physical therapists, pharmacists, and other allied healthcare professionals?

- As the previously discussed examples show, no financial incentive structure or reimbursement model is un-exploitable. While VBC holds a lot of promise and is championed by many, one of its biggest criticisms is that it encourages cherry-picking and lemon-dropping — just like POHs. There are a lot of parallels between POHs and VBC: committing to quality while being mindful of costs, making sure interests are aligned, and making sure those doing the work are rewarded for it.

- The “lawyers can own the law firm” argument in favor of POHs is slightly off. Physicians can own their own practices (although fewer and fewer are choosing to do so). Opponents would argue that POHs would be like lawyers owning the courts. But that comparison isn’t right either. Let’s just agree that such a comparison isn’t necessary to argue for or against POHs.

- Many POHs do not provide emergency services, something the AHA uses to argue against repealing the ban on the grounds that this is a form of cherry-picking. Interestingly, a bigger threat may be free-standing, independent ERs built in high-income areas. No stranger to this tactic, some health systems target areas with high concentrations of commercially insured patients for outpatient centers.

- What happens if/when Big Retail (or Big Tech — some have suggested Apple or Google should buy a hospital to better understand healthcare) decides to buy or build their own hospitals? Is that better or worse than POHs? One would imagine the AHA fighting just as hard against Amazon Basics Medical Center or Our Lady of Walmart Health.

This post first appeared on Dem Dry Bones on March 5, 2023. Read the original here: https://dembones.substack.com/p/physician-owned-hospitals

Commentary from Hospitalogy Subscribers

Comment 1:

Coming from a country (Spain) where many private hospitals were founded by physicians, the debate seems odd. It must be one of this very American things (my European self thinks). Jokes aside, American politics are very good at turning strategic discussions into doomsday scenario confrontations – I think POHs are not bad, and most likely not as bad as AHA wants to make it look like.

There’s one aspect I’m not in agreement with: to me healthcare should be patient led, not physician led. Asymmetry in clinical information is a historical trend, but hopefully one that will change soon. Following your baker/physician analogy, I can also bake my own bread – I normally decide not to because it’s a hassle, or I have 0 baking skills, or no ingredients. But I can. In healthcare almost anything I want to do is through physicians, sometimes now through mid levels. I’m not talking about surgeries – most definitely I’m not putting a blade to my body – but many areas of medicine are still physician dominated and could benefit from patient ownership. Genetics is one such example – quoting from AMA and inspired by Dr Topol’s book ” Since regulation of genetic tests is integral to physician practice and patient care, the AMA advocates to preserve the physician’s role in all aspects of patient care including the oversight of laboratory developed tests (LDTs)”. I’m not advocating for everyone to have to manage his or her own health, but definitely more ownership of my health data (crazy I have to ask for my results to somebody else), right to get a lab test without a physician prescription (I can do it in Europe btw) or access to certain drugs without prescription (statins?).

I fear many things in the fascinating world of healthcare, from PBMs – the Palpatine of Pharma – to AMA – the Dark Society of Alchemy and Necromancy, but what I fear the most in healthcare is paralysis. Change is not that terrible, so let’s open the door to POHs and see what happens. And let patients own more of their health.

Comment 2:

One other piece that could be interesting re: the hospital-ownership is that health plans are getting better at developing their patient steerage tools to high-value facilities. I think this transparency (reduction of information asymmetry) furthers the case you make.

Comment 3:

In a nutshell, none of the current evidence expressing concern about POHs can withstand the scrutiny of today’s AHA-driven cost model – one that opposes repealing noncompetes, sued over price transparency, and drives an unstainable administrative overhead.

That’s it for this week! Join 19,000+ executives and investors from leading healthcare organizations including VillageMD, Privia, and HCA Healthcare, health systems including Providence, Ascension, and Atrium, as well as leading digital health firms like Cityblock, Oak Street Health, and Turquoise Health by subscribing here!