28 January 2023 | FinTech

Big Banks’ Next Big Bet

By Alex Johnson

The big fintech news this week is that Early Warning Services (EWS) – a consortium of seven big U.S. banks – is developing a digital wallet:

Wells Fargo, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and four other banks are working on a new product that will allow shoppers to pay at merchants’ online checkout with a wallet that will be linked to their debit and credit cards.

The digital wallet will be managed by Early Warning Services LLC, the bank-owned company that operates money-transfer service Zelle. The wallet, which doesn’t have a name yet, will operate separately from Zelle, EWS said.

EWS, whose owners also include Capital One, PNC, U.S. Bank, and Truist plans to begin rolling out the new offering in the second half of the year.

This news gives me an excuse to poke around a question that I’ve been noodling over for a while – what is the future of big bank consortiums?

I’ll get to that question in next week’s essay.

For today’s essay, let’s try to figure out what this new digital wallet from EWS is and what its odds of success are in the eternally competitive world of consumer payments.

What is EWS building?

The wallet doesn’t have a name yet, so for the purposes of this essay, we’re going to call it Belle.

(Editor’s note – to be clear, I don’t know what this new digital wallet will be called. I’m almost positive they won’t call it Belle. If they do, please know I had no inside information on this.)

Here is what we know about Belle:

- It is being launched in order to counter the competitive threat posed to banks by third-party digital wallet providers. According to the Wall Street Journal, PayPal and Apple (especially Apple) are the competitors that the big banks are worried about. This is interesting because those mobile wallets are largely powered by payment cards issued by the big banks. So it’s apparently less of a concern about recapturing payment volume and more of a concern about being disintermediated from the end customer.

- Like PayPal and Apple Pay, Belle is being built on top of the card rails and will require a Visa or Mastercard debit or credit card to work. This choice was made in order to maximize customer adoption, given the comfort with and preference for payment cards among most consumers. EWS expects to enable roughly 150 million debit and credit cards for use within the wallet when it rolls out (U.S. consumers who are up-to-date on payments, have used their card online in recent years, and have provided an email address and phone number will be eligible).

- That said, the Wall Street Journal reports that “should a sizable number of merchants enable the wallet and consumers adopt it, EWS banks could explore adding other payment options, EWS said. That could include enabling payments directly from bank accounts.”

- Belle will be for e-commerce transactions, not in-person transactions, at least to start. EWS will be working directly with merchants to enable acceptance of Belle, and the end customer experience will, according to the Wall Street Journal, “involve consumers’ typing their email on a merchant’s checkout page. The merchant would ping EWS, which would use its back-end connections to banks to identify which of the consumer’s cards can be loaded onto the wallet. Consumers would then choose which card to use or could opt out.”

- Belle can be thought of as a direct descendent of Zelle, which EWS considered allowing consumers to use for online purchases, but concerns with fraud and the treatment of disputed transactions ended up shelving that plan.

OK, so that’s what it is. Second question …

Will it work?

To answer this question, we need to understand big banks’ intent1 in building Belle. What are they trying to accomplish?

According to the Wall Street Journal, the banks are concerned about the competitive threat posed by PayPal and Apple and are trying to ensure that they don’t just become the ‘dumb pipes’ behind these mobile wallets.

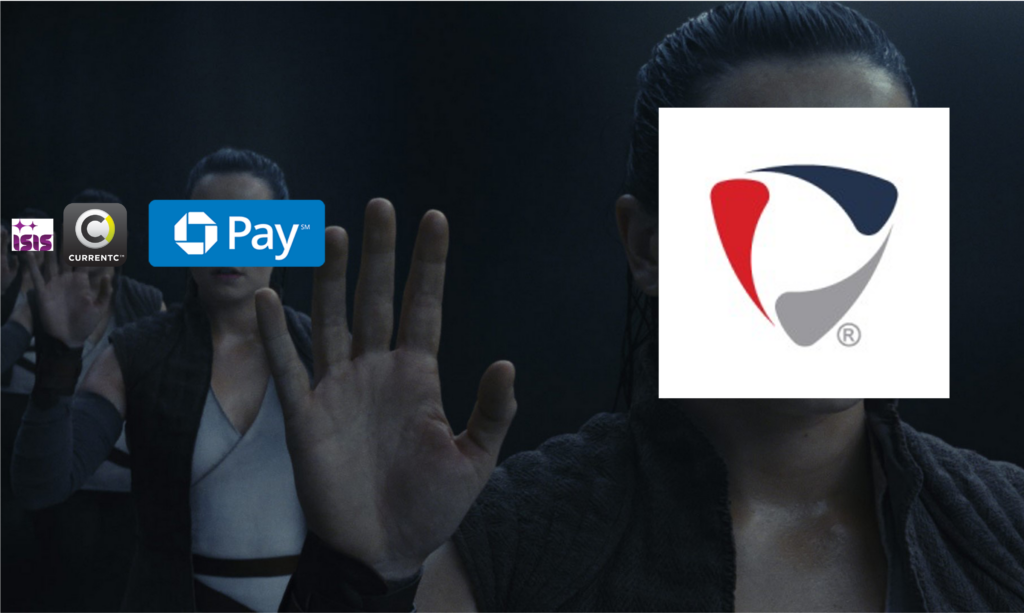

This is not a new fear. And there is a very long and colorful history of companies attempting (and mostly failing) to build digital wallets in order to seize control of the payments value chain.

In 2010, we had the big wireless carriers developing Isis (later rebranded to Softcard) in an attempt to control their own mobile wallet and payments network:

The venture known as Isis, formed by AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile, initially aspired to set up its own payments network and collect fees on every transaction. Customers would maintain accounts directly with their wireless carrier, rather than with a credit card company.

Isis failed and was scooped up by Google in 2015, which incorporated some of the tech and IP into Android Pay, which was launched in response to Apple Pay, which had debuted to great fanfare the year before.

In the middle of all this, you also had MCX (a consortium of large merchants) launch, with the intent to bring its own non-card mobile wallet (CurrentC) to market and provide merchants with an alternative to credit cards and their annoying interchange fees. This project ended in embarrassment in Columbus, Ohio, in 2015, having failed to garner any interest from consumers, and was sold to JP Morgan Chase.

Chase took the lifeless husk of CurrentC and grafted it onto its own proprietary digital wallet – Chase Pay – which launched in 2015 … and was shut down in 2021, having achieved, at its height, a merchant acceptance rate of around 1%.

All of this is to say – it’s not easy.

And the failures (and successes) that we’ve seen in this area over the last two decades provide some useful lessons for EWS and Belle.

Lesson #1: If you’re not solving an important problem for the consumer, you’re dead.

In all of the competitive mania over the last 20 years, with everyone trying to build the next great digital payments solution for consumers, it was surprisingly common to see companies completely forget about the consumer.

Consumer: OK, I want to buy this thing, and I need a way to pay for it. Who wants to help me?

Literally every company on Earth, simultaneously: We do!

Consumer: Calm down. One at a time. Tell me why I should pick you. You first [points at the Visa and Mastercard].

Visa and Mastercard: We’re safe, we work everywhere, and we will give you rewards.

Consumer: [taking notes on a clipboard while talking] OK, cool. Thanks. Next.

BNPL Providers: We work in all the places where you actually want to shop, we’re convenient to use, and we make your purchases less expensive up front! And also, credit cards are evil [Visa and Mastercard roll their eyes].

Consumer: Great. Next.

Apple: We are safe and rewarding because we use the payment cards you already have [winks in an exaggerated way at Visa and Mastercard]. We’re the most convenient option because you use your iPhone, which you always have with you. All you need is your fingerprint or face. Plus, I mean, come on, we’re Apple.

Consumer: Solid points. OK, next.

Walmart: We hate Visa and Mastercard.

Consumer: What?

Walmart: We hate them [stares at Visa and Mastercard without blinking].

Consumer: And…

Walmart: And using us to pay for things will cost them money and hurt them, and that’s what we want, and that’s what you should want too.

Consumer: [sliding char back from the table a tiny bit] Okaayyy, and last but not least [points to the big banks].

Big Banks: Well, you already use our payment cards, which is great, thank you, but we’re worried that you like Apple more than us [Apple waives cheerfully], and it would make us feel better about ourselves if you used our cards and our new mobile wallet.

Consumer: Uhuh. Well, OK, I have everything I need. Thanks. I’ll be in touch.

U.S. consumers are generally pretty satisfied with the current ways that they pay for stuff, and getting them to change requires you to deliver significant new value. That value could be convenience (Apple Pay for e-commerce in a mobile browser), cost savings (BNPL pay-in-4), rewards (cashback funded by interchange), or something else.

It can’t be “we hate interchange” or “we’re afraid of being disintermediated.”

The takeaway for Belle: There was nothing in the Wall Street Journal article that really even hinted at customer value. The experience it described – enter your email and choose an available card to use – is a bit more convenient than entering your card details manually, but it’s not anywhere close to the convenience offered by Apple Pay, and arguably it’s not as convenient as PayPal or Amazon Pay or any of the other options crowding the checkout page.

Plus, it’s not clear from that description how customer verification and fraud management are going to be handled. How is EWS going to be verifying that I am who I say I am if all I’m doing is entering Alex Johnson’s email address (which is, sadly, very available on the internet)? Apple handles ID verification at the device/OS level. PayPal, Amazon, and the rest handle it through customer credentials. How is EWS going to handle it, and how much friction will that add to the experience?

Lesson #2: It’s hard to add value if you’re also subtracting value.

Everyone in this space starts out wanting to cut the card networks and their interchange fees out of the equation.

And yet, everyone eventually gives in (or dies).

Isis pivoted away from building its own payment network to building on top of the card networks:

the group has adopted the less ambitious goal of setting up a “mobile wallet” that can store and exchange the account information on a users’ existing Visa, MasterCard or other card, people familiar with the matter said. The carriers are scrambling to find other ways to make money from the transactions.

To get as many users as possible, the carriers are now in talks with Visa and MasterCard to have them participate in the system they will embed in phones, people familiar with the matter said.

PayPal knuckled under and stopped steering customers to ACH and away from cards:

Currently, its users can link their PayPal accounts to a bank account or to a credit card. The company encourages them to do the former, because it allows them to dodge the steep fees charged by card issuers and networks such as Visa and MasterCard.

In Thursday’s deal, PayPal agreed to stop steering users in this direction. As a result, more customers will likely link their accounts to credit cards to take advantage of cashback and other rewards. This will raise the company’s costs significantly on all kinds of PayPal payments.

Even Apple decided not to create its own alternative payment network, although it did manage to wring some great concessions out of Visa and Mastercard:

Visa and Mastercard also agreed to give Apple an unusual concession, according to people familiar with the matter: Apple would be able to choose which issuers it would allow onto Apple Pay and which of those issuers’ cards it would accept. Visa and Mastercard generally require that entities that accept their credit cards must accept them all. Apple agreed to not develop a card network to compete against Visa and Mastercard, the people said.

The reason why cutting the card networks out of digital payments is so hard is because, by doing that, you are subtracting value. It doesn’t seem like that to the companies building the wallets (cut those interchange fees!), but it does to their customers. Consumers like debit cards and credit cards. They like the built-in safety and consumer protections. And they really like rewards. Some companies try to get around this problem by offering their own rewards, paid for by the interchange savings, but this isn’t easy – consumers don’t understand why they should give up the rewards they know and like for rewards that they don’t know and that probably aren’t as good.

Motivating consumers to change their payment behavior is a difficult equation to solve on its own. Subtracting value from consumers makes it much harder.2

And yet, companies persist:

The new system being developed by JPMorgan’s corporate and investment bank — the CIB — would enable merchants to receive payments directly from consumers, cutting out the need for debit or credit cards and posing a threat to the lucrative fees earned by banks and dominant card companies Visa and Mastercard.

The takeaway for Belle: EWS and its bank owners are showing wisdom in supporting debit cards and credit cards from day one. As the Wall Street Journal article hinted at, EWS is considering adding other payment rails into the solution (including payments directly from consumers’ bank accounts) if they succeed in scaling up merchant and consumer adoption. I’m skeptical that EWS will get to that point, but this is the right order of operations.

Lesson #3: Getting merchant adoption is really hard.

As payments has gotten more competitive over the last couple of decades, it has become increasingly difficult for aspiring disruptors to achieve anything close to ubiquitous merchant acceptance.

In-person payments is challenging because the most obvious avenue for achieving large-scale merchant acceptance for a mobile wallet – near-field communication (NFC) – isn’t an option if you’re hoping to serve a majority of the market, thanks to some anti-competitive flexing from Apple. The only other viable route for in-person payments dominance is to own both the mobile wallet and the POS terminal (is that Square dancing music I hear?).

Online payments is challenging because everyone is trying to get their payment button onto those checkout screens. E-commerce merchants are inundated with inbound pitches for “seamless new digital payments tools” that, they are told, they simply must test out. There is very little room for new entrants here, and the gatekeepers have become jaded and price sensitive.3

The takeaway for Belle: Credit to EWS, I suppose, for recognizing the inevitable and not trying to attack in-person payments. That would be suicide.

However, I don’t know that they’re going to have a lot more luck with online payments. It’s not like EWS has a long track record of successfully selling to e-commerce merchants. And even if they did, what’s the pitch?

Well, it’s credit cards and debit cards, so you’re not going to be saving any money, and the customer experience isn’t any better than any of the other payments tools that you’re already integrated with (and it’s clearly worse than some), and we’re not bringing any net-new customers into your ecosystem or giving them extra rewards or special financing, but everybody loves their bank, right?

BNPL gained huge ground in e-commerce over the last few years by offering a clear and critical value to merchants – more sales. Players like Shopify, PayPal, and Square offer an integrated ecosystem of solutions for merchants, of which payments is only one part.

Belle will need to find something similarly compelling if it’s going to reach escape velocity.

Final Verdict

I don’t see it. I get why EWS is taking a shot at this target (everybody does, eventually), but there just isn’t enough value to consumers or merchants for this to grab market share in a crowded field.

Bonus Analysis

For a different, though similarly skeptical take on this news, I would recommend that you watch Jason Mikula, Nick Holland, and Ian Horne’s recent chat and read Ron Shevlin’s excellent article on this topic.

You might also find Tom Noyes’ prescient-though-somewhat-indecipherable blogs on this topic interesting.