04 November 2022 | FinTech

What is a Bank?

By Alex Johnson

I became deeply interested in this question last year, when Chime, the most popular neobank in the U.S., was ordered by the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (DFPI) to stop referring to itself as a bank and to make it clear to its customers and prospects that the actual banking services it offers are provided by third-party bank partners:

The San Francisco-based company has been the subject of a yearlong investigation by the California regulator for using “chimebank.com” as its web address prior to February 2020, and for using the terms “bank” or “banking” in its business.

Chime is also ordered to clarify in paid Google search results and ads that its banking services are provided by its bank partners, and is required to identify the partners by name.

The fintech is required to clarify in the frequently asked questions section of its website that its bank accounts are held at partner banks, and must “provide a clear and prominent disclaimer during the account set up process to inform the consumer that Chime is a financial technology company not a bank.”

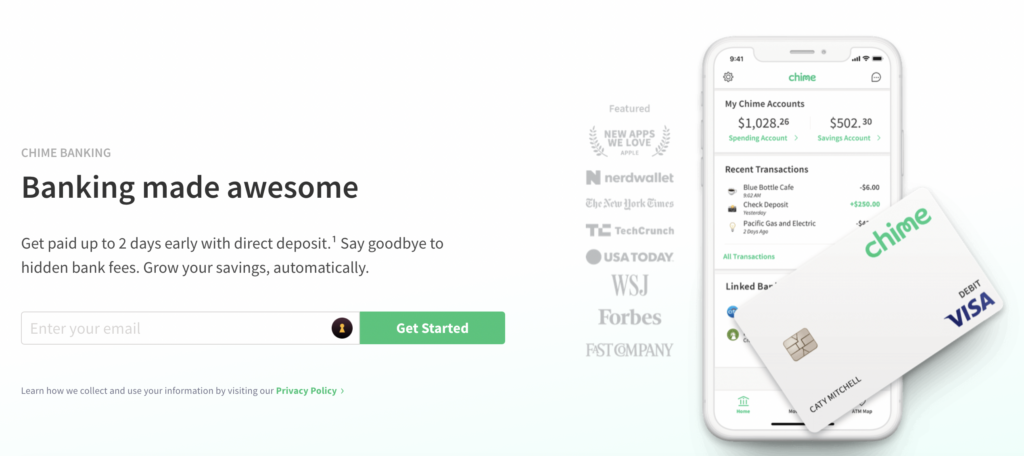

In practice, this order (and Chime’s compliance with it) transformed the homepage of Chime’s website from this:

To this:

And my reaction to this change, wrought by the vigilance of California DFPI, was, at the time, something like this:

Whoa! So much more clear! Now there is no possible way that a consumer would ever mistakenly think that Chime is a licensed bank rather than a financial technology company! They’ll also totally grok what a “financial technology provider” is and what “banking services provided by” means!

Like, come on. Were consumers really confused by this? Did the elimination of the words “Chime Banking” and the addition of the ‘Chime is not a bank’ disclaimer in small text really make a difference?

That was my opinion.

And then this happened almost exactly one year later:

Last year, Keith Baldwin took his savings and bought USD Coin, putting it in a crypto account that paid a 9% annual yield.

In April, he moved it into a pseudo-savings account powered by TerraUSD that offered 15%. More than 90% of his savings vanished in a few days when TerraUSD lost its peg to the dollar. Dr. Baldwin said he didn’t know that Stablegains, the startup that managed the account, was converting his USD Coin holdings into TerraUSD.

When Dr. Baldwin learned that TerraUSD’s troubles were threatening his nest egg, he scrambled to withdraw his funds from Stablegains. Hours ticked by as the site processed the transfer. By the time they landed at Dr. Baldwin’s newly created account at the Kraken crypto exchange, the coin was trading at just 14 cents.

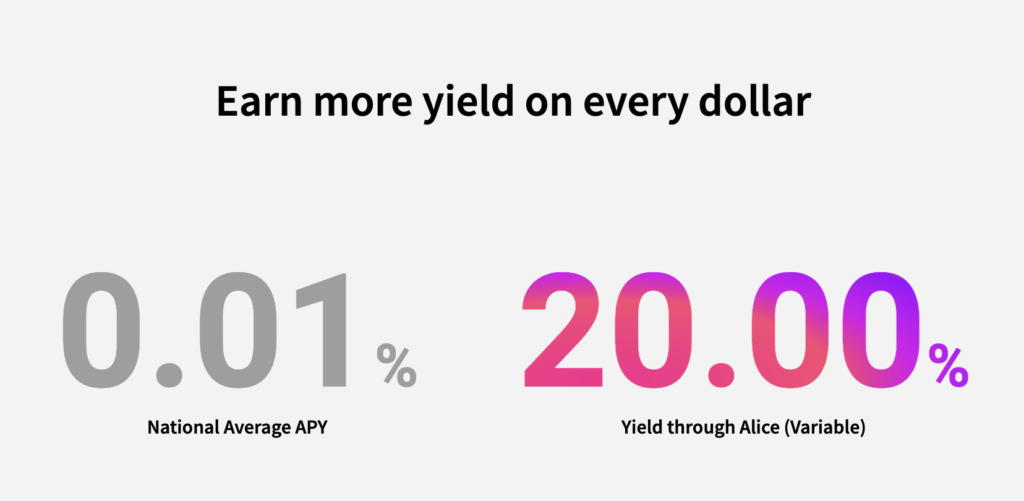

The collapse of the TerraUSD algorithmic stablecoin had a devastatingly wide impact on consumers because Terraform Labs (the creator of TerraUSD) had created Anchor Protocol, which was essentially an SDK that any fintech or DeFi app could integrate and use to convert their customers’ money into TerraUSD, collect the 19.5% APY yields offered as an incentive by Terraform Labs, and pass some or all of that yield back to their customers as ‘interest on their deposits’.

Fintech apps, luckily, didn’t do this. But a bunch of DeFi apps did, and they used this ‘feature’ to sell their customers on the idea that they were providing a better version of a bank account:

This, of course, was complete bullshit. The 20% yield was being financed by a pyramid scheme, and there was no protection for customer funds when that pyramid scheme was sucked into a death spiral, as Keith Baldwin discovered.

Anchor Protocol was California bank regulators’ nightmare scenario, brought to life. Terra weaponized banking terms like ‘deposits’, ‘yield’, and ‘APY’ and gave them to DeFi app developers to use to attract consumers’ money.

And it provided me with a sobering lesson on the importance of language in signaling trust, which is, and always has been, the north star in financial services.

Which leads us back to our question – what is a bank?

The fun (and frustrating) thing about this question is that there’s not just one answer. There are a bunch of different answers, depending on the perspective you take. Some answers may be a little more technically correct than others, but all of them are useful in that they help us understand what’s happening to the financial services industry today and where it’s going tomorrow.

Let’s hop through a few different answers I’ve been thinking about.

Real quick, though, before we do that, I want to give a shoutout to the inestimable Kiah Haslett, who is probably the only person in the world more fascinated by the question of ‘what is a bank?’ than I am. She wrote an entire article about it last year, and she has been an invaluable resource for me while writing this essay. In particular, she shared an old essay written by E. Gerald Corrigan, a former president of both the Federal Reserve banks in Minneapolis and New York and a managing director at Goldman Sachs & Co., called “Are Banks Special?” that is an absolutely incredible read for banking nerds. Thanks, Kiah!

OK, now back to the answers.

The Classical Mechanics Answer

I think the answer we need to start with is the one grounded in what banks actually do and the Newtonian mechanics of how they actually work. From this perspective:

A bank is a company with the unique legal ability, conveyed by a bank charter, to raise cheap, short-term, insured capital, make loans, and facilitate money movement.

Simon Taylor, in his infuriatingly elegant way, summed it up like this:

Damnit. I really like that. Only banks have balance sheet power.

And because this mechanical definition hinges on the special legal status of banks, this is the answer that I think most closely fits the view of most bank regulators, including the OCC and state regulators like the California DFPI.

Indeed, if a regulator were to use this framework to segment the market and try to divide ‘banks’ into logical subgroups, they might come up with something like this:

- Traditional Banks. This is the vast majority of the market. Established financial institutions (meaning older than three years) that have the required federal and/or state charters. Think Chase, Huntington, Glacier Bank, and the like.

- Neobanks. The small but highly disruptive group of financial technology companies (not banks!) that operate on top of the charters and infrastructure of traditional banks. They are digital-only and are usually focused on serving a very specific customer segment with a focused product set. Think Chime, Current, Dave, and the like.

- De Novo Banks. Literally, ‘a new bank’, these are banks that have recently sought and obtained regulatory approval for a new bank charter. Most of these resemble traditional banks, but usually, with a branch-light, tech-forward distribution model (think Locality Bank, Studio Bank, and Grasshopper). Varo is the odd duck in here, as it started out as a neobank (digital only, limited product set, aggressive growth targets) but successfully obtained a new bank charter, the same as any other de novo, and is now trying to become a profitable, well-capitalized bank.

- Fintech Acquirers. In contrast to Varo, this has been the more common route for fintech companies to obtain a bank charter – they buy an existing bank. It’s not any easier than the de novo route, in terms of securing regulatory approval, but it’s a bit easier to navigate after securing that approval (keeping a profitable bank running is much easier than building a profitable bank from scratch). Think SoFi, LendingClub, and Jiko.

The Quantum Mechanics Answer

Someone told me a funny story once about trying to get a job at a neobank.

The folks interviewing them asked, “what is a bank?” and this person started to answer the question by explaining net interest margin and how a bank makes money, and before they could finish, the interviewers cut them off and said:

A bank is a ledger.

This answer is simple, but not incorrect.

If you reduce banking down to its most fundamental level and strip everything else away, what we’re doing is essentially facilitating and keeping track of payments in and out of different accounts. Those accounts could be held at two different companies, with a third party (like Visa) helping to facilitate the movement of money between them. Or it could be two accounts at the same company, and the ‘movement’ of money between them is accomplished simply by shifting numbers from one column to another. To the ledger, it’s all the same.

This tends to be the way that engineers and other first-principles thinkers conceptualize banking, and it has its advantages, as Current (a neobank that built its own core banking system and ledger) is fond of explaining:

Because Current owns its ledger, it can now perform a variety of transactions itself such as debit, ACH, direct deposit, peer-to-peer payments, mobile check deposits, cash deposits, points rewards and points redemptions. And a customer can have balances across multiple underlying issuing banks, since different banks can handle different features and have different economics.

The Old Fintech Pitch Deck Answer

If you tried to parse out the answer to the question “what is a bank?” from the aggregated pitch decks of all the B2C fintech companies that raised money from VCs in the last 10 years, you’d likely come to the conclusion that:

A bank is an elitist, soul-devouring profit machine designed to screw over the little guy.

This, of course, was by design. The founders of neobanks and other B2C fintech companies were selling the idea that traditional banks were ripe for disruption because they were terrible at serving their customers and their customers, consequently, hated them. Here’s a representative example from MoneyLion’s SPAC deck:

There was some truth in this framing (overdraft fee revenue far exceeded the value that overdraft protection was providing), and there was a lot of exaggeration (consumers’ dissatisfaction with traditional banks is almost always overstated).

However, the most important thing was that VCs were buying what B2C fintech founders were selling.

The New Fintech Pitch Deck Answer

Until recently.

As the wave of consumer-facing fintech companies that went public (via either IPO or SPAC) in 2020 and 2021 discovered, public market investors aren’t buying the ‘we’re not a bank, we’re a software company’ argument. And that sentiment, along with the slowdown in VC funding and the general weirdness of the economy right now, has rippled its way back through the private fintech market, all the way to earliest-stage B2C startups.

Today, based on the pitch decks that I have been seeing, the definition of a bank in early-stage pitch decks is more like:

A bank is a tough competitor and also a potential partner and distribution channel.

In the current fundraising environment, in which VCs seem to be almost allergic to any kind of B2C pitch, B2C fintech founders are being both much more realistic (acknowledging that competing with banks directly is going to be extremely difficult) and more collaborative (positioning the idea of banks being good distribution and product innovation partners) in the way they are talking about banks.

This is a major shift.

Jay Powell’s Answer

He-who-would-destroy-inflation-at-any-cost would probably answer this question like this:

A bank is one of the most important tools in my toolbox.

Through adjustments to the Federal Funds Rate (the rate at which banks can lend and borrow excess reserves to and from each other), the Federal Reserve can dramatically shift the cost of borrowing, for both consumers and businesses, which in turn drives huge shifts in overall economic activity and sentiment.

Seen through this lens, banks are a major lever for U.S. government monetary policy, as E. Gerald Corrigan astutely pointed out decades ago:

The fact that banks are subject to reserve requirements places the banking system in the unique position of being the “transmission belt” through which the actions and policies of the central bank have their effect on financial market conditions, money and credit creation, and economic conditions generally. To put it somewhat differently, the required reserves of the banking system have often been described as the fulcrum upon which the monetary authority operates monetary policy. The reserves in the banking system also serve the complementary purpose of providing the working balances which permit our highly efficient financial markets to function and to effect the orderly end-of-day settlement of the hundreds of billions of dollars of transactions that occur over the course of each business day.

And based on the latest news – U.S. employers added 261,000 jobs in October, and American workers continued to see strong wage growth – it doesn’t seem like Chairman Powell is going to stop hitting us in the face with that tool anytime soon.

Rohit Chopra’s Answer

OK, remember, we’re not asking the Director of the CFPB about a specific bank, which depending on the institution we chose, might elicit a rather negative response.

Instead, we’re asking him (in this fun thought experiment) a more philosophical question – what is a bank?

I think it’s possible he might answer with something like:

A bank is an indispensably important participant in a thriving community, especially a rural community.

In recent comments, Director Chopra stressed how concerned he was about the disappearance of small community banks:

In 1984, the United States had nearly 18,000 banking institutions. Last year, that number declined to fewer than 5,000. What was once a decentralized consumer finance landscape, primarily populated by local financial institutions, is now dominated by large banks that have gobbled up many of those small players.

When Main Street banks pack up and leave town, and when issues are instead funneled through national call centers, there is a loss of local, on-the-ground knowledge that is the basis of good customer service, and good banking.

And the disappearance of the type of banking they practice – relationship banking:

Relationship banks do not create fake accounts or pass the buck when customers face problems. A key element of relationship banking is one where banks respond to customers with clear answers, can translate into better banking for individuals but also for the banks. When banks put effort into service, responsiveness and customer care, problems get solved and customers get the products that best match their needs.

As I noted in a prior essay, this focus on community banks and relationship banking is odd. It suggests that banks, beyond the mechanical function they provide within the broader economy, also play an important role in keeping their local communities strong and vibrant. And if this is true, it suggests that perhaps we, as a society, should go out of our way to protect certain aspects of relationship banking (branches? Human tellers and loan officers?) against the forces of creative destruction.

Merry Christmas, you wonderful old Building and Loan!

The Embedded Finance Evangelist’s Answer

What if we posed our question to a passionate advocate of embedded finance? Like Bain & Company, for example. What might they say?

I think it would be something like this:

A bank is an anachronism in today’s market, a category of customer-facing companies that have been rendered obsolete by software.

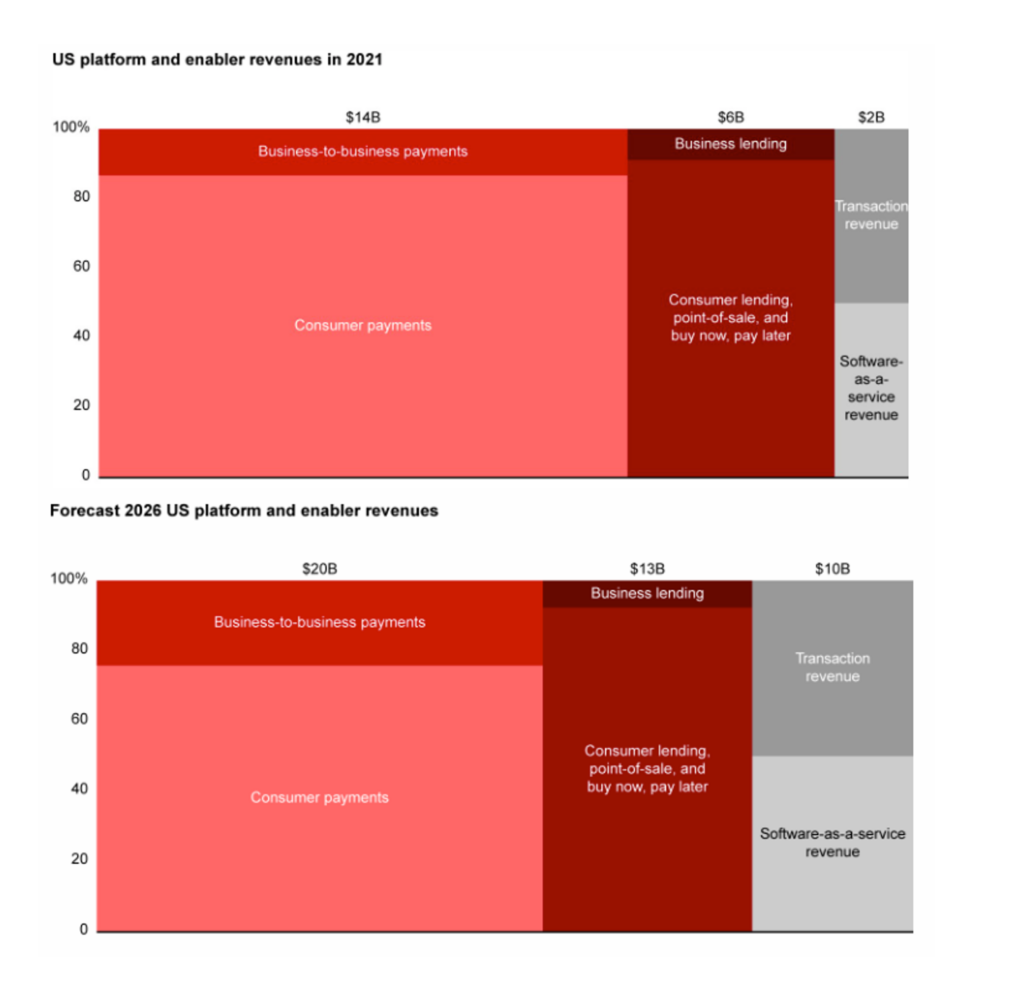

In a recent report, Bain defined embedded finance as:

a nonfinancial software platform providing an adjacent financial service, for which it takes some degree of economic ownership. This allows the platform’s customers to take advantage of a value-added offering within the native customer journey.

And predicted that the overall market for embedded finance in the U.S. – cutting across payments, lending, and banking – would more than double from $22 billion in 2021 revenue to $51 billion by 2026.

The argument being made here is that embedded finance is categorically better for customers; less expensive (because non-bank providers can cross-subsidize), more personalized (because these non-bank platforms have tons of data about their customers), and more convenient (because you are presenting the financial product directly within the activity that the customer needs it for).

From the perspective of an embedded finance zealot, standalone, customer-facing banks don’t make sense anymore and won’t be able to compete with embedded alternatives. Banks will instead retreat to the infrastructure layer where they, along with fintech infrastructure providers like Plaid and Stripe, will focus on enabling the embedded finance economy.

The Consumer’s Answer

The last perspective and the most important – what do consumers think a bank is?

Every stakeholder in the industry has their own (somewhat selfish) take on this.

Regulators like to believe that consumers confine their definition to only directly licensed and regulated financial institutions.

Neobanks, DeFi apps, and other fintech companies hope that consumers define a bank as the company that best helps them address their most pressing financial needs.

Embedded finance evangelists would prefer to believe that the idea of a ‘bank’ will eventually fade entirely from the memories and imaginations of consumers.

None of these are quite right.

I believe that consumers’ answer to this question is:

A bank is a safe place to keep, access, and understand my money.

Let’s unpack that a bit.

First, I would argue that standalone, consumer-facing banks will always exist because, as compelling as I find the vision of embedded finance, I do not believe that it will ever render consumer-facing banks obsolete.

Why?

Embedded finance makes sense as long as the financial product is in service of the non-finance activity that the consumer is trying to complete. Embedded payments within the Uber app make sense because I’m just trying to get to my destination as quickly and smoothly as possible. I don’t want the process of paying the driver to get in the way. Indirect auto lending is similar – I want to buy the car and drive off the lot. The loan is merely a means to an end, and I want to spend as little time thinking about it as possible.

Deposit products aren’t transactional the way that payments and loans are. A checking account doesn’t exist to facilitate some other, non-finance activity. It is its own thing with its own standalone utility. I may divert a small amount of money into my Starbucks app every month to fund my coffee addiction, but there’s no way in hell I’m moving my whole direct deposit over to Starbucks.

As a consumer, I want to have a dedicated home base for my money, and I want a combination of software tools and qualified human beings available in that home base to help me understand my money and what I can and should be doing with it. This is a role that banks are uniquely suited to play.

Second, I would argue that the single most important job of a bank account is to ensure that the money that is in there today will be in there tomorrow. A feeling of safety is paramount. This isn’t a rational thing that you can overcome with carefully constructed arguments. It’s primal.

This has a couple of interesting implications:

- Crypto-native ‘bank’ accounts are a bad idea. Anchor Protocol is the glaring example here, but I think this also applies to the more responsible corners of the crypto ecosystem (Eco has an entire article on its website that attempts, unsuccessfully in my view, to explain why most people don’t actually need FDIC insurance). A government backstop for consumer deposit products is essential.

- BaaS-enabled neobanks can be safe, but the details matter. FDIC insurance sits at the foundation of this model. That’s the good news. Consumer deposits are safe. And I don’t believe that consumers are particularly fussed if they are directly working with a financial technology company or with a licensed bank, as long as this is true. However, the details of these BaaS arrangements matter a ton. Are you using an FBO accounts structure? If so, how do customers access their funds if you go out of business or experience a prolonged service outage? If you haven’t nailed down the answers to these questions, you haven’t satisfied this requirement for safety.

What is a Bank … To You?

My thoughts on this question have evolved quite a bit in the last couple of years. I’m sure they will continue to. And I’d love to know – what is a bank … to you?