21 October 2022 | FinTech

What Fintech Forgets About Consumer Lending

By Alex Johnson

Here’s a simple axiom:

It’s incredibly easy to give away money … the challenge is getting it back.

If you’ve attended a financial services conference (especially recently), you’ve probably heard this statement being tossed out by a presenter or panelist. Depending on the conference, it may have been me!

I know it sounds trite, but the reason that folks who have been in financial services for a while like to share this reminder is because, while it is trite, it’s also fiendishly difficult to remember in the moment.

Just in the last 5-10 years, we’ve seen multiple generations of fintech companies forget. Person-to-person (P2P) lenders forgot, circa 2015. And I think it’s likely that at least some of the big BNPL providers that saw explosive growth between 2019 and 2021 forgot as well (we’ll have to wait at least another 12-18 months to find out for sure).

Why is this simple piece of advice difficult to remember?

My theory is that companies, particularly startups and particularly tech companies, are designed to process and respond to feedback quickly. It’s all about iteration. You create a minimally viable product (MVP), you put it out there, you measure the response from your target customer segment, and you adjust. You keep doing this as quickly as possible until you either run out of money or you hit on a version of your product that gets significant traction. And if you’re lucky enough to get significant traction on one of the many versions of your product, you immediately switch into growth mode. You pour as much money into customer acquisition as possible, and you scale up!

It’s all very linear and immediate.

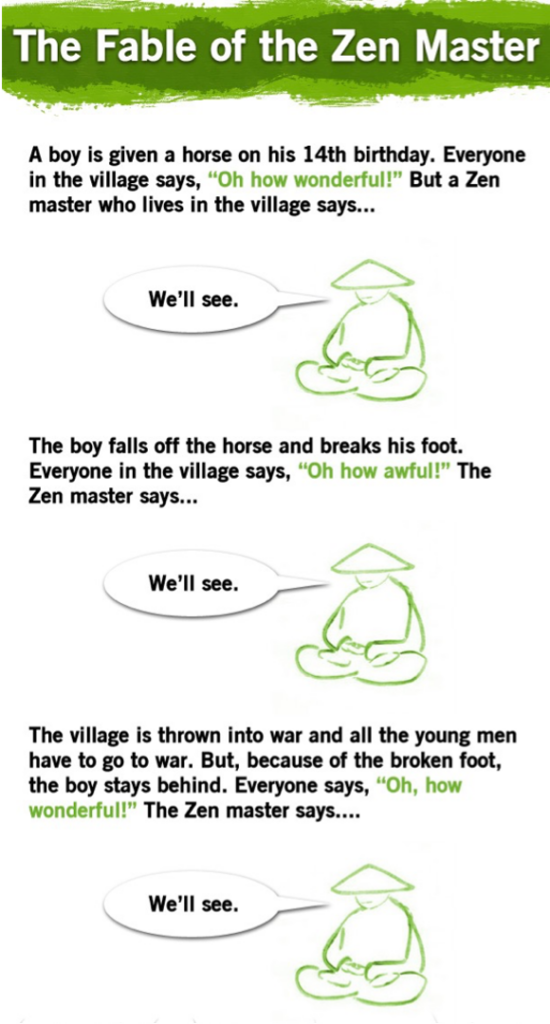

Lending isn’t like that. Talking to an experienced credit risk professional, when their company is in the midst of launching or iterating on a new lending product, is a lot like talking to a Zen master:

Everyone Else: Hey! We just launched the credit card yesterday, and the response has been great. We already have 10,000 new customers. This is wonderful!

Credit Risk Professional: We’ll see.

Everyone Else: Jeez, we tightened up our lending criteria and our approval rate dropped by 40%. We’re not going to make any money. This is terrible!

Credit Risk Professional: We’ll see.

Everyone Else: Wow! We figured out how to streamline our digital account opening process, and we’ve upped our application throughput by 25% without having to loosen our lending criteria at all. This is great!

Credit Risk Professional: We’ll see.

The problem with lending is that, at certain points and under certain conditions, there is a negative correlation between customer acquisition and profitability. And knowing what those points are and what those conditions are is an art, not a science. You can’t avoid this problem by building a better algorithm. You avoid it by employing people who have personally experienced the problem before.

This is why experienced financial services folks often say – lending is a learning business.

So, in that spirit, here’s another trite-sounding piece of advice that I want to share – sustainably successful lending requires striking the right balance between the amount of money lent and the level of assurance that the customer is required to provide.

Striking the Right Balance

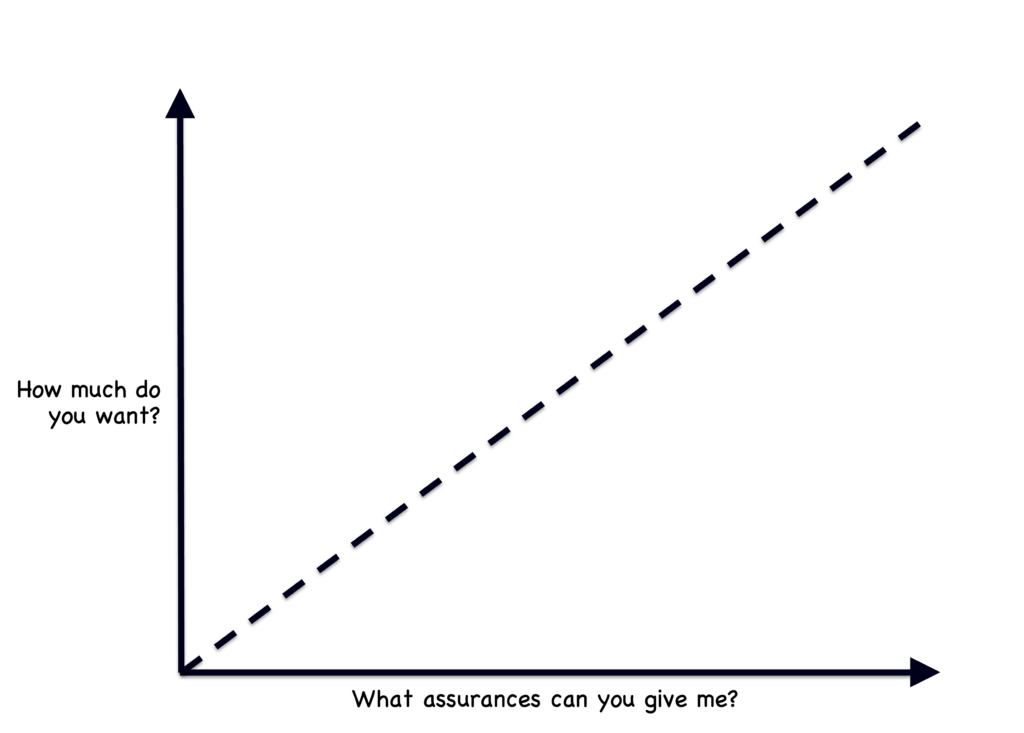

I know this is a vast oversimplification, but I think it’s useful.

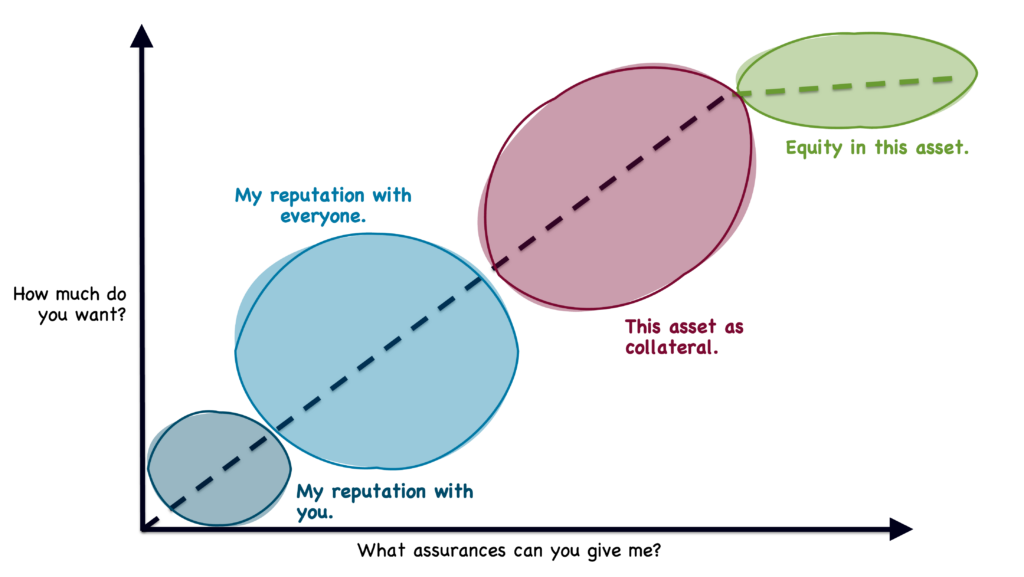

Let’s imagine that you have a graph. On the y-axis, you have the amount of money you (the lender) are willing to lend to a consumer. On the x-axis, you have the level of assurance that you require that consumer to provide you with in order for you to lend them the money.

The relationship between these two independent variables is exactly what you’d imagine – as you move up on the y-axis (amount of money you are willing to lend), you move a similar amount to right on the x-axis (level of assurance you require from the customer). It is, roughly speaking, a linear function.

In order to operate a profitable lending business for a long period of time, you need to stay relatively close to this line.

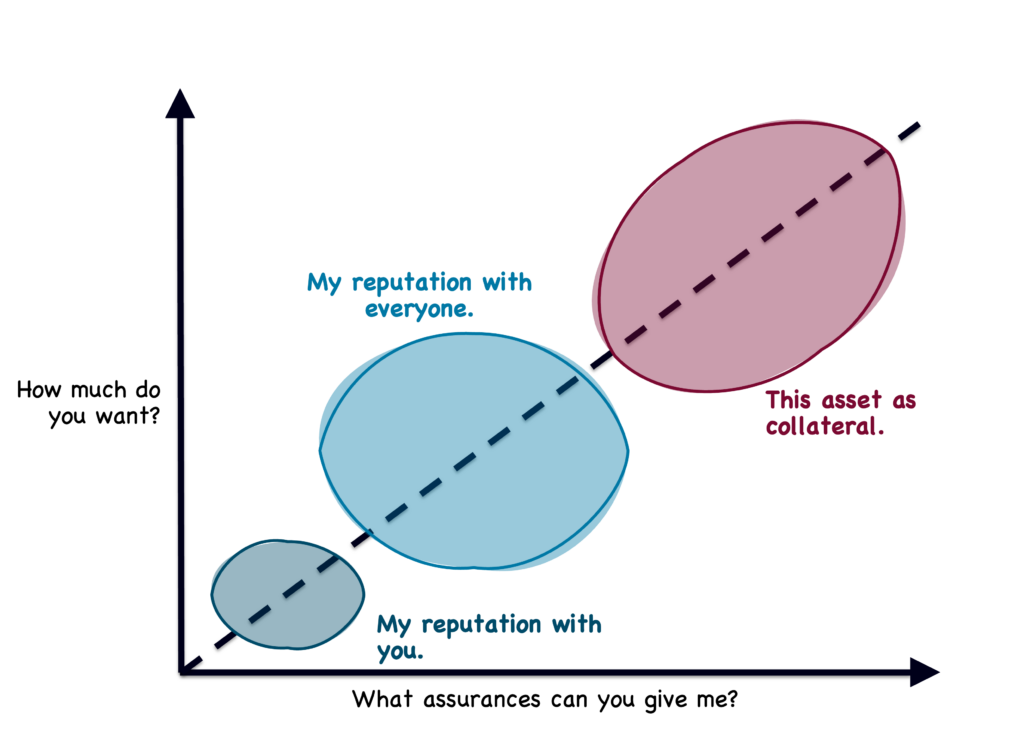

And if we look at the totality of consumer lending happening today, I think we can break it up into three ‘zones’ on this graph, which all rest on this line. These three zones are:

1.) Relationship Lending. The lender is willing to loan a relatively small amount of money to a consumer based on the relationship that they have with the consumer. The consumer is, essentially, staking its reputation with that lender in exchange for the money. Consumers with lengthy, positive borrowing relationships tend to get access to more money and better pricing than those with less history. Lenders utilizing this model are often rather unforgiving with consumers that have defaulted with them in the past.

2.) Credit Score Lending. The lender is willing to loan larger amounts of money to a consumer based on the relationships that the consumer has with all of the lenders they have ever worked with. In this model, the consumer is risking their reputation with all lenders. If they screw you over today, they jeopardize their ability to borrow from your competitors tomorrow. Borrowers’ aggregated reputations are captured in their credit reports and expressed in general-purpose credit scores like the FICO Score.

3.) Secured Lending. The lender is willing to loan large amounts of money to a consumer based, largely, on the value of the asset that the consumer is borrowing money to buy. In exchange for the loan, the consumer gives the lender the legal right to take ownership of the asset if they default on their loan payments, which allows the lender to recoup a significant portion of their losses in that scenario.

For most of human history, relationship lending dominated. With the advent of the credit bureaus and, later, general-purpose credit scores, much of that unsecured lending volume shifted to the credit score lending model.

Secured lending has always existed in roughly the form that it exists in today because it’s really the only way to lend money at that scale safely.

It’s important to note that these zones build on top of each other. Lenders that rely on credit scores for unsecured lending will still take their relationships with specific borrowers into their decisions – profitable, low-risk customers get VIP treatment (better pricing, streamlined experience, etc.) while customers with prior defaults will often be blacklisted (automatically declined or given additional screening). For securitized lending, lenders will usually supplement their asset-based underwriting with general-purpose credit scores in order to help them gauge a consumer’s willingness to repay. This is important, as often the value of the asset won’t fully cover the lender’s losses in a full-scale default (think of auto lending, where a decent chunk of the value of the car vanishes as soon as it is driven off the lot).

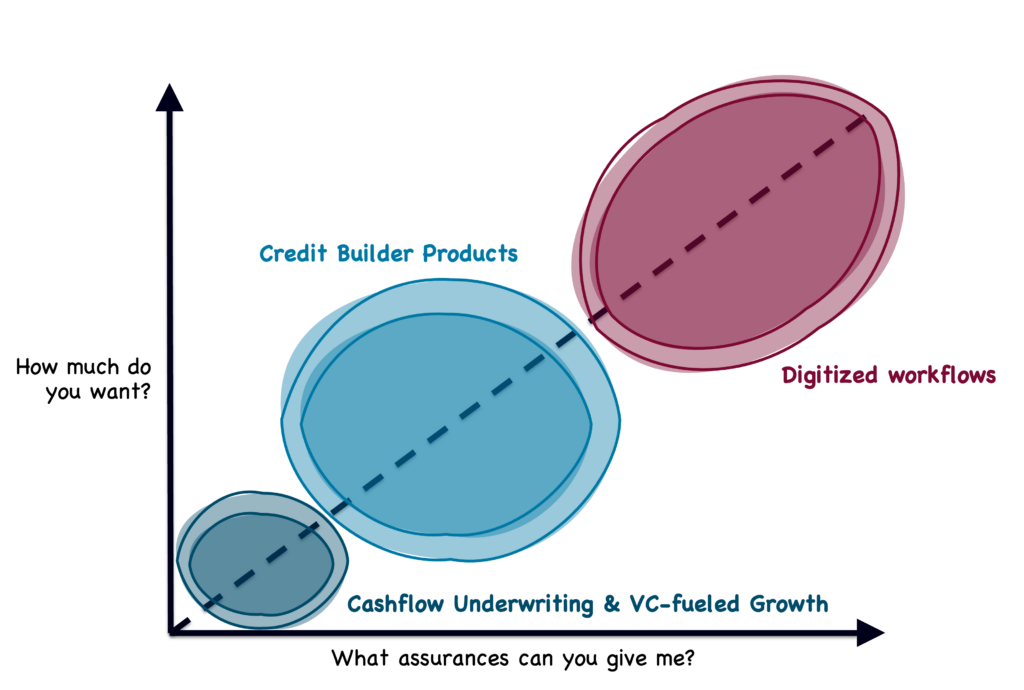

Now, what’s really interesting is that fintech – as it is wont to do – has pushed the boundaries of these three lending zones in a number of different ways, some good and some bad.

Fintech Pushing the Boundaries

1.) Relationship Lending. The advent of credit scoring pushed relationship lending out of vogue. Most banks abandoned the idea of cultivating new customers with small-dollar loans and slow, incremental increases in creditworthiness. Instead, they just went out into the market and looked for established customers that already had prime credit scores. Unsecured lending became more hunting and less farming.

This left a gap in the market – credit invisible customers – which fintech companies quickly stepped in to address.

Some fintech companies, like Petal, introduced unsecured credit products designed for credit invisible customers (young adults, recent immigrants, etc.), which relied on alternative underwriting strategies like cashflow underwriting. These alternative strategies helped offset the initial credit risk and allowed these companies to establish the foundation of a larger relationship, which they hope to build as their customers’ financial habits and needs mature.

Other fintech companies, like the big BNPL providers, simply took on more risk in lending to this segment of consumers, in the hopes of quickly weeding out the goods from the bads and establishing profitable, long-term relationships with the best customers. Pay-in-4 BNPL loans are ideally suited to this strategy because they are low-dollar (typically less than $250) and have short terms (six weeks). This approach was also enabled by the ‘risk-on, everything-goes-up-and-to-the-right’ funding environment of the last few years, in which BNPL providers were encouraged by VCs to spend lots of money and take on lots of risk in order to grow as quickly as possible.

2.) Credit Score Lending. The big fintech innovation in this zone is the development of credit builder products that assist consumers in quickly establishing and/or improving their credit scores, with the goal of giving those consumers more leverage in borrowing from other lenders in the future.

The problem with many of these products – as we discussed in depth in this essay – is that the repayment data that they are furnishing to the credit bureaus is not reliable as a signal of their customers’ willingness to pay, which will likely result in the benefits provided by these products being muted over time, either by individual lenders adjusting their credit risk models or by the credit bureaus tightening up their requirements on data furnishers.

3.) Secured Lending. Innovating in secured lending is much harder than it is in unsecured lending. The loans are bigger, with longer terms. There is a great deal more regulation to deal with. And dealing with the asset in the center of the transaction generally requires a lot of paperwork and wet signatures.

Fintech companies’ progress in innovating in secured lending has been much slower, but as the old saying goes, slow progress is lasting progress. And we’ve made some significant progress over the last couple of decades.

Take residential mortgage lending as an example.

In 1996, Rock Financial (a regional branch-based mortgage broker in Detroit) tried mailing all mortgage documents directly to its customers in a so-called “Mortgage in a Box,” so customers could complete the application from the comfort of their home.

20 years later, Quicken Loans (the descendent of Rock Financial) launched a fully digital mortgage experience – Rocket Mortgage – that was the first time a consumer could go from application to closing on their own, without speaking to a human.

Three years after that, Quicken Loans became the largest mortgage lender in the U.S.

By digitizing and streamlining secured lending, fintech companies have made the process significantly more efficient and the experience significantly more enjoyable. This has both served to supercharge customer acquisition (consumers always gravitate to convenience) and to make secured lending more profitable (by lowering operational costs, it’s now economical for lenders to work with customers that it wouldn’t have been before).

Overall, fintech has expanded the effective surface area of these three lending zones, sometimes in ways that are sustainable (cashflow underwriting, digitized workflows) and sometimes in ways that are not (VC-fueled growth, credit builder products).

That’s great … and interesting … but it’s not the end of the story.

Buying Equity

Our story ends with fintech companies trying to figure out how they can further expand the effective surface area of consumer lending, by moving beyond securitized lending and into equity investing.

Here’s the pitch:

What if I can offer you money, which you can use for whatever you want? Don’t worry; it’s not a loan! You’re not taking on debt or paying interest. You don’t need to have a good credit score … or any credit score at all! We are completely aligned with you. We only make money if you make money.

Sounds good. Vastly more appealing, on the surface, than a loan with all those scary interest rates and annoying minimum credit score requirements.

There’s just one little catch – instead of repaying a loan, you are selling a portion of the equity that you own in a specified asset.

Which asset?

Well, there are two examples I want to talk about:

1.) Income Share Agreements (ISAs). The way an ISA works is that a student (at a public university, private university, or a vocational school) receives a sum of money in exchange for a promise to pay back a percentage of their future pre-tax income (ranging from 2% to 20%) for a set number of months. The contracts typically cap the total amount users will ever have to pay back and include an income floor so that if their earnings fall below it, they pay nothing. But the payment caps can be as high as three times the funded amount, and some ISAs include a prepayment penalty if the student tries to get out of the contract early.

Put simply, ISAs allow students to pay for school by selling stock in themselves. And that is an apt analogy because ISAs have investors, in the same way that venture capital funds do. Here is how a news story about Purdue University, which had recently been offering its own ISA program, put it:

It’s essentially like an investment portfolio filled with hundreds of students from dozens of majors. Some students will do well, and others not so much. But combined, the fund is expected to grow.

“Nobody’s going to get really wealthy the way this is set up,” [Purdue President, Mitch] Daniels said. “But you might get a reasonable return, and in Purdue’s case, we’d put the money back into the next set.”

Besides Purdue’s own foundation, other foundations and even individual investors have bought into the fund, which has now invested nearly $14 million in more than 850 students.

2.) Home Equity Investments (HEIs). HEIs work in a similar way, except instead of splitting future income gains with an investor, the consumer is splitting a future increase in the value of their home with an investor. When you sign up with an HEI provider, you type in your home address, get an estimate for how much money the provider might be willing to invest, apply for the investment, receive the funds, and then (after the end of the contract term, which can be anywhere from 10 to 30 years, typically) you settle up with the HEI provider by either selling your home (and splitting the increase in value with them) or buying them out (and paying them for their stake in your house at its new valuation).

ISAs and HEIs don’t enable consumers to access more money than their secured/unsecured loan counterparts. However, they do lower the short-term costs for consumers (no interest!) and make money available to more consumers (no credit score needed!). And both types of products are delivered in a slick digital experience.

ISAs and HEIs are, simultaneously, descendants of the fintech innovators that proceeded them (the experience of getting an HEI appears very Rocket Mortgage-y) and aberrations in the historical progression of consumer lending innovation.

And now, please allow me to end this essay with one paragraph of pure (possibly unfair) editorializing.

I absolutely hate this trend. ISAs and HEIs are presented as more aligned and democratic ways to get money into the hands of consumers. They are presented as products that limit consumers’ downside risk through smart financial engineering. That’s horseshit. Building actual wealth requires taking on downside risk. These products are funnels designed to channel equity away from cash-strapped consumers and into the pockets of cash-rich, yield-hungry investors. And if we return to my trite piece of advice earlier in this essay – sustainably successful lending requires striking the right balance between the amount of money lent and the level of assurance that the customer is required to provide – I think we can conclude that these products are not striking the right balance. Regulators are already beginning to turn up the heat (ISAs have gotten a ton of regulatory scrutiny in the last couple of years) and it’s my sincere hope that this trend – swapping in investment risk for credit risk – burns itself out soon.

Fin.