15 October 2022 | FinTech

How Fintech VCs Can Actually Be Helpful

By Alex Johnson

“Let me know how I can be helpful.”

This is a sentence that has been so frequently written by VCs, often at the end of an email explaining why they aren’t investing in a startup, that it has become a meme.

But you know what? In today’s essay, we’re going to take them up on that offer.

In today’s essay, we’re going to talk about the absolutely abysmal rates at which female founders and founders of color in fintech raise capital and provide some feedback to VCs on how they can actually be helpful in getting those rates to move in the right direction.

Let’s start with some numbers.

Female Founders and Founders of Color are Massively Underfunded

In 2021, a banner year for VC investment in fintech, only 2% went to companies founded by women. 1% went to Black founders. 1.8% went to Latinx founders. And, applying an intersectional lens, if you were raising in 2021 as a Black Woman or Latinx woman, your chances were basically zero.

This data mirrors the data from another report, which found that “VC-backed startups are still significantly male (89.3%), white (71.6%), based in Silicon Valley (35.3%) and Ivy-educated (13.7%).”

This is not only bad, it’s stupid.

Studies have repeatedly demonstrated that companies founded by diverse teams outperform those with less diversity. For example, companies with diverse founders earn 30% higher multiples on invested capital when they are acquired or go public.

So why, then, are these funding numbers for diverse and underrepresented founders still so embarrassingly low?

There are a lot of different ways to answer that question, but I think one of the most useful ways to answer it is by examining the first-hand experiences of women and people of color who have gone through the fundraising process.

To do that, I spoke with dozens of female founders and founders of color within the fintech space (along with a few other keen observers of the fintech VC ecosystem). I have aggregated their stories, observations, and reflections below.

But before we get to that, a couple of quick notes:

- All the interviews I conducted for this essay were done off the record and on deep background. This was, quite simply, the only way to do it. Fintech (and tech generally) is a small world, and the founders I spoke with were justifiably nervous about harming their reputations with VCs by speaking candidly with me on the record.

- The focus of my interviews was on the early-stage fundraising process (pre-seed and seed, primarily) and I mostly spoke to folks focused on the U.S. market. Obviously, the challenges outlined in the essay extend well beyond both early-stage companies and companies in the U.S.

- If you want to dive even further into this topic (and you should), I’d suggest reading the WTFintech? newsletter by Nicole Casperson (my Workweek colleague). She has been writing passionately and persuasively about a lot of these topics for a long time, and her work (particularly 3 Steps to Fixing Fintech’s Diversity Problem, The Origin of Tech’s Diversity Problem, and a16z’s Latest Investment Exposes VC) was incredibly helpful in shaping my thinking for this essay. Also, if you’ll be in San Francisco on November 10, you should absolutely attend Nicole’s Fintech is Femme event.

- Finally, I just want to say how grateful I am to all of the folks who helped me put this essay together, including and especially the female founders and founders of color who were willing to share their experiences with me. Thank you.

And now, let’s examine why the process of raising capital from VCs is so difficult for female founders and founders of color in fintech.

Why is it Difficult for Female Founders and Founders of Color to Raise?

Early-stage investing is all about the person, not the idea or the product.

This, I think, sits at the heart of the problem. Investing at the pre-seed or seed stage is almost entirely a bet on the founder(s). As a female founder explained:

Funding first-time founders is really hard. How will this person do? It’s harder to build conviction. At pre-seed and seed stages, there’s not much data to go on. You’re really just judging the person.

Sure, founders will prepare pitch decks explaining the market problem and painting a picture of the addressable market size, and giving their thoughts on a sustainable customer acquisition strategy, but really the early-stage fundraising process is about sitting down across the table (real or virtual) from the VC, looking them in the eye, and convincing them to believe in you.

And that, as a founder of color explained to me, is a task that can be easily derailed:

Bias really comes into play in early-stage investing because they are investing in the founder. There is no company yet; there are no numbers to evaluate. If they don’t believe in you, you don’t get money. Period.

Bias is really hard to recognize and correct for.

When your job is to judge other human beings, it’s impossible not to be biased. However, bias can lead to poor business decisions; as one female founder put it:

In early-stage investing, biases tend to revolve around implicit assumptions that we, as an industry, have about what successful fintech founders look like. A founder I spoke with called this archetype “top-of-the-pile founders”:

Top-of-the-pile founders are the ones that check all of the explicit boxes – graduated from a target school, technical, repeat founder, between the ages of 20 and 35 – and, of course, a lot of those founders are going to be White men. And that, by itself, is problematic because a lot of potentially great founders might not have those characteristics. But it’s also bad because it trains our brains to think that all young White men should be top-of-the-pile founders, regardless of their backgrounds.

That same founder went on to explain that everyone is subject to these biases, even her when she was on the investor side of the table:

Bias is tricky. I’m like the least likely person to let these biases drive my decisions, but when I was on the investment side, and I was across the table from a White guy with a Stanford undergraduate degree in engineering and an MBA in economics, who comes from a wealthy background with a strong network, I’m catching myself thinking ‘yeah, this guy is smart. He should be an easy yes.’

And for female founders and founders of color, who end up on the wrong side of these subtle biases, it can be really difficult to even understand what’s happening. A female founder who I spoke with elaborated:

It’s not usually flat-out discrimination. It’s bias. That’s subtler and harder to detect. It’s ‘I don’t quite believe you’ and ‘I’m not sure you can pull this off’. And obviously, the counterfactuals are impossible to prove. Did he not invest because he genuinely didn’t like the business opportunity, or is it because I’m a woman?

So, as a female founder or founder of color, you learn to recognize the bias implicit in the little comments that VCs make; the ones you can’t imagine them making to a White male founder. The female founders I spoke with had lots of rather infuriating examples:

I get a weird amount of comments about my attire in pitch meetings.

I’ve had VCs express concerns about how aggressive my tone is on social media.

I have been asked in multiple pitch meetings about Elizabeth Holmes. I’m nothing like Elizabeth Holmes, except I’m a white woman with blond hair. Do white men with dark hair get asked about Adam Neumann when they pitch to VCs?

I was told in a pitch meeting, ‘my wife wouldn’t be interested in this.’ I never said his wife would be interested in it. I never said it was targeted at women.

I was asked if I was having a third kid.

I was told, ‘oh, your husband works, so you can play with this founding thing.’

And, of course, you notice this bias much more clearly in the success that other, comparable companies are having in fundraising, as several female founders shared with me:

There are competitive startups, founded by men, building shittier versions of my product and out-fundraising me by 5-1. It’s hard to see that and not think that it’s at least a little bit about my gender.

There is a company at our same stage, that is building a very similar product to ours, that was founded by four men, all Harvard dropouts. They were younger than us. They didn’t have a product. They were nowhere on compliance. And they outraised us by a significant margin. Their seed round was oversubscribed. They raised on hype.

VCs have an incentive to prioritize their existing networks.

Compounding the problem of bias is the fact that VCs have a strange incentive to invest in founders from their existing networks, even when some (a lot?) of those investments are predictably bad.

A recent research paper out of the University of Chicago’s Booth business school came back with an interesting conclusion:

Do institutional investors invest efficiently? To study this question I combine a novel dataset of over 16,000 startups (representing over $9 billion in investments) with machine learning methods to evaluate the decisions of early-stage investors. By comparing investor choices to an algorithm’s predictions, I show that approximately half of the investments were predictably bad—based on information known at the time of investment, the predicted return of the investment was less than readily available outside options. The cost of these poor investments is 1000 basis points, totalling over $900 million in my data. I provide suggestive evidence that over-reliance on the founders’ background is one mechanism underlying these choices.

Interesting! Why might VCs be making such easily-avoidable mistakes at such a high rate? Here’s Matt Levine:

VC funds have to invest in the bad companies in order to get access to the good ones. I don’t quite know how this would work. … But it could work something like: “Founders choose their venture capital investors through some sort of reputational network; they talk to their founder buddies about which VCs are helpful and good to work with. If a VC rejects too many Stanford-dropout founders by saying ‘sorry my algo says that your company is bad,’ then the Stanford-dropout founders with good companies will hear about that from their Stanford-dropout friends, and won’t want to work with that VC. Making bad investments is a way to be part of the club, and being part of the club gets you the deal flow that gives you the good investments.”

Logical, but not great for those not in the club already.

VCs can’t empathize with most problem statements.

Another challenge for female founders and founders of color is that they are often focused on solving problems that VCs can’t personally relate to, as a female founder I spoke with explained:

A different female founder concurred and observed that the reason that you see so much investment in certain categories (like corporate cards and banking for startups) is that VCs understand those problems because they have personally experienced them:

Pitching to VCs is problematic because VCs, as a consumer segment, have a small TAM and are already way oversaturated, and yet … the product ideas that get the best traction with most VCs are the ones that VCs inherently get as consumers. This is why corporate cards for venture-backed startups are so popular among VCs. They instantly get the problem and the value prop. Many women and people of color are focused on solving problems for consumer segments that VCs can’t personally relate to.

And, by contrast, this same female founder argued that VCs will become far too pessimistic about other categories:

A lot of VCs won’t touch certain categories of Fintech, like PFM, because they invested in the category before and got burned. That sucks because a lot of the ideas that crashed and burned were started by White men who weren’t close enough to the problem to be able to solve it. I am close to it, and I can solve it. But the result of their crash and burn experience is that they won’t invest in that category again, but they will happily invest in the failed White male founders because they are now repeat founders.

A founder of color pointed out that one of the strategic values of having diversity on the investment side of the table is that you can catch these opportunities that might otherwise be missed:

Diversity is important because, if you don’t have it, you might miss the mark. Imagine you are in an investment committee meeting, and all the folks at the table are White men, and they are evaluating this app that is built for barbershop owners; there won’t be anyone in that room who can explain how important barbershops are to the Black community. I personally won’t move to a city without a good barber. If someone put Squire on your desk, two rounds ago, would you have invested in it?

And speaking of the importance of having diversity inside VC firms …

Fintech investors aren’t diverse.

In 2020, women made up 45% of all employees at VC firms, but just 16% of investment partners. For Black people, these percentages were 4% and 3%, and for Latinx people, it was 7% and 4%.

The obvious problem here is that not enough women and people of color are in positions of authority and influence within the VC ecosystem.

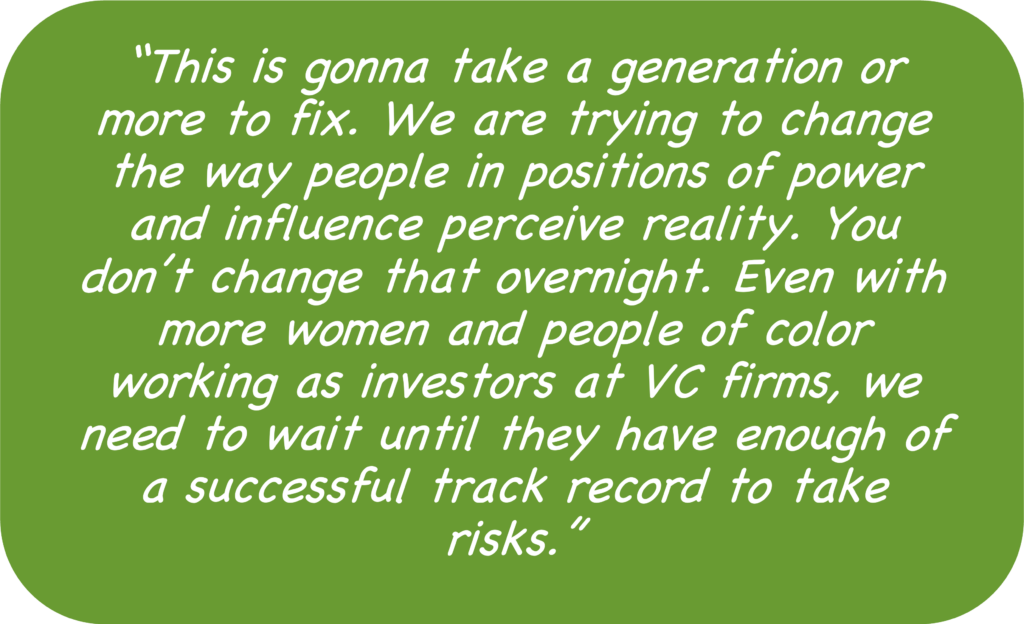

The more subtle problem is that even the women and people of color who are in those positions aren’t yet (for the most part) secure enough in them to take big risks, as a female founder related to me:

You always get referred to these female investor funds. They say, ‘well, you’re a woman. You should go talk to them.’ What you discover is that these funds focused on investing in female founders are super conservative. They do a ton of due diligence. They only want to back startups that are profitable already. And they are more comfortable investing in categories that are already well penetrated by female founders – like e-commerce and MarTech – than they are in male-dominated categories that they don’t understand really well, like fintech.

A founder who is a woman and a person of color concurred:

A lot of diverse investors at both impact and non-impact focused funds are actually as conservative or more conservative as White male investors when it comes to investing in diverse founders because a lot of them are still trying to prove themselves to their managing partners and LPs. I think that’ll change eventually, as these investors build more of a track record, but it’s a challenge right now.

Fundraising is an unsolvable math problem for female founders and founders of color.

Another challenge that came up repeatedly in my conversations is how astonishingly inefficient it is for female founders and founders of color to raise from VCs. One female founder described it in very memorable terms:

It’s like a math problem that even the smartest female founders and founders of color can’t solve. VCs take a ton of meetings for every one investment they make. That’s fine. That’s their job. The problem is that a founder’s job is to raise the money they need efficiently and then get back to building. They can’t waste their time taking hundreds of meetings and not getting a single check. The burden of this math problem falls, almost entirely, on female founders and founders of color. White male founders, who have the odds on their side, don’t see this. To them, fundraising is, maybe, a bit challenging. To women and people of color, it’s a nightmare.

Everyone I spoke with emphasized how frustrating it was to waste their time pitching VCs who were never going to invest:

Are you trying to show your LPs that you are taking meetings with female founders and founders of color? If your motivation is to check a box, you are not helping. You are wasting my time.

A lot of venture capitalists will take a meeting with you because they don’t want to not take a meeting with a female founder. But at the end of the meeting, they’re like, ‘this sounds great. We’d love to get involved in your next round.’

Time is the most important thing. Each conversation that is a no or a lingering no, it eats me a little bit. It’s death by a thousand paper cuts. Spare me of that. Don’t waste my time.

A lot of first-time founders don’t understand how VC works.

One of the factors that contribute to this inefficiency is a lack of understanding among founders of how the VC business model works. A founder of color who I spoke with described it this way:

You have to understand the VC business model. A lot of founders, particularly first-time founders and founders of color, don’t. It’s not about having a good idea for a business. It’s about having a venture-sized good idea for a business. Most ideas aren’t venture-backable.

This lack of understanding leads founders to both pitch the wrong ideas and to pitch the right ideas to the wrong investors.

Underrepresented founders don’t have strong networks.

Building this understanding and getting access to the right VCs is difficult if you don’t have a strong network, which many female founders and founders of color don’t. Two different female founders I spoke with made this point:

The size and influence of your network matters a lot, and women are at a big disadvantage on this front.

The lack of direct access to this network is a killer. I didn’t know any VCs. I didn’t know anyone who could get me a warm introduction to the right VCs.

Underrepresented founders are at a storytelling disadvantage.

Pitching your startup is an art, in and of itself. And it’s one that women struggle with, according to a female founder I spoke with:

Women pitch where they are. Men pitch the future. It makes for an apples-to-oranges comparison. No wonder we don’t do as well as men at fundraising.

A founder of color who I interviewed agreed:

Arrogance gets in the way.

And even if your pitch is right on the money, many VCs (particularly the less experienced ones) simply won’t believe it, as two different female founders described:

The level of arrogance that a lot of VCs have is breathtaking. They will be absolutely sure, after 5 minutes of listening to me, that my thesis isn’t right.

A lot of VCs I pitched to were absolutely sure that they knew better than me, even though they are two years out of Stanford and I’ve worked in this industry for 20 years.

VCs aren’t being honest.

Many of the founders I interviewed expressed frustration that VCs simply weren’t honest with them about why they weren’t investing, which made it extremely hard for the founders to adjust and get a better outcome from their next meeting:

The goalposts are constantly moving. It’s Lucy and the football – come back when you have [insert whatever new milestone or metric they can think of]. I would do that and come back, and they still wouldn’t invest.

All the feedback I got was wildly inconsistent. They would be like ‘you need to be more bold’, and so I’d be more bold, and then they’d be like, ‘I just don’t think you’re being realistic.’

The lack of clarity is the problem. If it’s a no, just be honest and try to be as honest as you can be about why it’s a no. Don’t waste my time. Don’t muddle my process.

Underrepresented founders are under tremendous pressure to derisk.

Female founders and founders of color also reported feeling an intense and unfair pressure to derisk themselves and their businesses as much as possible, in order to make it fractionally more likely for a VC to write them a check. Even if the steps taken to derisk themselves and their businesses weren’t, objectively, the right things to do.

One female founder shared this with me:

When you are raising a seed round, you have two choices. You can take the biggest and boldest version of your idea and pitch it. Pitch something that is super ambitious and would be a venture-sized return if it works. Pitching that way required you to basically flip the fucking table over in the pitch meeting and pound your chest. A.) that’s not the way I talk to people, and B.) they wouldn’t believe me if I tried to do it. So I go with the second option – scale the idea down, focus on a smaller segment, get some market traction, bootstrap the business a bit, get some revenue and users, and then pitch the smaller idea. This works better, but it also sucks because I’m going to get $1.5 million for my seed rather than $5 million.

Another female founder had a similar early experience:

Investors kept telling us, ‘we can’t invest if you don’t have a product’, so we rushed to get our app ready and in market. We would have preferred to take our time, but we had to derisk ourselves. And then the investors looked at the app and said, ‘well, this isn’t very good’ and we said, ‘well yeah, we pulled it together in like eight weeks!’

But, of course, there’s only so much you can do by derisking your business. The real objection that a lot of VCs have at the early stages is about who the founder is, as one female founder explained:

An angel investor told me, ‘I want to write you a check, but just being brutally honest – as a woman, I don’t think you’ll be able to convince enough other investors to write you checks down the road.’ He said, ‘I’ll fund women who are starting companies with a shoestring budget, but if you are starting a capital-intensive business, there’s too much capital risk.’ Sadly, that’s a very rational position.

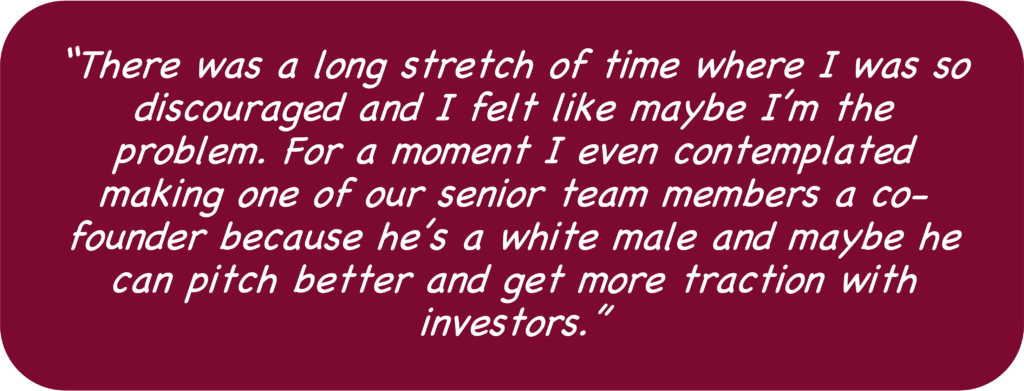

And this leads female founders and founders of color to consider radical solutions, as another female founder shared:

The fundraising experience often feels unsafe and/or unwelcoming.

According to a recent survey, investors prefer to meet with founders in person, either at industry conferences or recreational events or happy hours. However, in that same survey, female founders reported a strong preference for meeting with investors virtually.

I think there are a few reasons for this.

First and most seriously, in-person meetings with strangers present a very real safety risk. Multiple female founders who I spoke with shared that they had experienced incidents ranging from uncomfortable physical contact to sexual assault when meeting with potential investors. One of these female founders said simply:

Investors, first and foremost, need to make the fundraising process feel safe.

Beyond physical safety, female founders also described fundraising experiences in which they felt taken advantage of:

Here’s a pattern I’ve learned to recognize – a VC meets with me, hears my pitch, and takes lots of notes (which seems like a positive sign!), and then doesn’t invest. Then, a few months later, I see a lot of my ideas being implemented by a different (male-founded) company in that VC’s portfolio. Me and my female founder friends have a term for this – brain rape.

Another reason for preferring virtual meetings over in-person meetings is that virtual meetings allow founders to better control the personal information that they share about themselves, as one story from a female founder illustrates:

I was pregnant while raising my seed round, and I started the process being very open about it because I just thought, ‘I wouldn’t want an investor that had a problem with that to invest in my company.’ We weren’t getting any traction, and I was told by multiple angels that had already invested in my company that being honest about this was really hurting my odds. All these pitches were over Zoom, so they told me, ‘just hide it during the next few pitches and see what happens.’ Two of the next five pitches resulted in checks being written.

There is a huge intention–action gap.

Most of the founders who I interviewed believe that most VCs in the ecosystem have good intentions. They want to fix this problem.

The issue is that these good intentions don’t translate into action.

A great example of this gap between intention and action is the abundance of mentors available to underrepresented founders, as one founder of color shared:

Black founders are some of the most over-mentored and under-funded folks you’ll ever come across.

A female founder agreed and made the case for why mentors, while mildly useful, do little to actually address her challenges:

I’m sick of mentors. I need people who are willing to get their hands dirty. I need real advocates who will put their names and relationships and money on the line. I don’t need a mentor handing me pearls of wisdom. That’s bullshit. Take actual risks.

What are Some Potential Solutions?

This isn’t going to be an easy problem to solve. If it was easy, it would have been accomplished a long time ago by those with good intentions and cold feet. As a female founder told me:

There is no silver bullet.

There are, however, lots of great ideas that folks shared with me for how we can make this situation incrementally better. Most of these ideas are, rightly, aimed at what investors can do better. However, there were a few great suggestions that the founders I spoke with had for other founders.

Investors: Help founders understand the dynamics of venture-backed businesses.

This was emphasized to me repeatedly. VCs assume that everyone in the world understands the nuances of their business as well as they do. This is obviously not true, and founders would benefit enormously from some education on this front.

Here’s one specific example that a founder shared with me:

VCs need to help female founders and founders of color get comfortable taking bigger risks and spending their time and money in ways that will maximize their leverage. A good example is executive assistants. A lot of seed and series A-stage female founders and founders of color view EAs as an unaffordable luxury. That’s not right. Hiring an EA is about getting more leverage on your time as a founder.

Founders: Do way more due diligence on investors.

This was some wonderful advice from a female founder:

It’s important to do due diligence. I ask VCs how many women do you have in your portfolio? How many women have you worked for in the course of your career? How many female partners do you have at your firm? What does the rate of promotion look like for associates and junior partners at your firm, and how does that rate differ between men and women? I really like to ask male VCs what their wives do for a living. In my experience, if their wives are high-powered professionals, the VC will be more open to listening to women and taking them seriously, and writing them checks.

Investors: Stop mentoring and put your money and/or reputation on the line.

It can make all the difference, as one female founder stressed to me:

A lot of my success raising money happened once an old white man became an advocate for me. He took me to everyone in his network, and he helped me raise. That’s how I built my seed round – from a bunch of individual rich people who I would never have had access to without this guy.

Founders: Consider incubators, venture studios, and accelerators.

You are likely surrendering more equity than you’d ideally like to, but applying to and participating in these programs can be worth it for the access to their networks and for the way it can derisk you in investors’ eyes:

Venture studios and incubators are really helpful for first-time founders and female founders and founders of color because they work with you to derisk the business and put you in a great position to enter the market in a strong position.

We went through YC, and the experience was great. It opened up a lot of doors for us, and we started getting a lot more inbound interest from investors. YC was the first one to take a bet on us. We wouldn’t have been able to raise without the YC stamp on us.

Investors: Don’t waste founders’ time.

Your desire to impress your LPs with how many meetings you’ve taken with diverse founders or to constantly be gathering intel on what others are building doesn’t justify or excuse you wasting the time of female founders and founders of color who you’re not going to invest in. Don’t take the meeting if you’re not serious.

Founders: Pitch the damn thing.

This might not be for everyone, but I personally loved this suggestion from a female founder:

The secret we learned for raising money is simple – act like a dude. Go into the pitch meeting and tell them how much money you’ve raised and how much more you are looking for. Give them a deadline and tell them ‘it’s now or never’. Adopt a fuck you attitude. Trying to have an open dialogue and build relationships does not work.

Investors: Self-censor more.

It was the unanimous opinion of the founders I spoke with that VCs would benefit from a bit more self-censorship. It can be hard to understand the impact that a seemingly benign comment about someone’s attire can have. So, when in doubt, don’t say the thing you are thinking about saying.

Investors: Be curious, not judgemental.

Borrowing this one from Coach Lasso. Here’s a healthy assumption when you don’t understand what a founder just told you – maybe they know what they’re talking about, and you might be missing something important. Ask questions. Schedule a follow-up call. Dig in more.

Founders: Do what’s right for your business.

I understand the temptation to take every step to derisk your business and yourself in the hopes of improving your odds of getting funded. However – real talk – it won’t move the needle much anyway, and it will lead you to make decisions about your business and product that you will likely regret. Don’t bend on this. There are other avenues to raising capital.

Investors: Hire women and people of color and give them check-writing authority.

This is a big one. Female investors and investors of color will have advantages in both sourcing and evaluating opportunities with underrepresented founders. VC firms should prioritize hiring these people and giving them check-writing authority as quickly as possible. Treat this task with urgency. Every minute that you aren’t doing this, you are missing out on opportunities that they might help you catch.

Investors: Prioritize the comfort and safety of founders.

Go out of your way to make the environment in which you hear pitches and interact with founders feel as safe and comfortable as possible. Lean more towards virtual meetings and large group meetings. Don’t require female founders or founders of color to meet you in social or recreational settings.

Investors: Share your data.

We can’t improve if we can’t measure where we are today and how much progress we’ve made. Sharing data on the diversity of portfolios and employees should be considered table stakes. The data I really want to see – perhaps in an anonymous and aggregated way – is where investors are sourcing their pipelines from. That would tell us a lot about the size and diversity of VCs’ networks.

Investors: Build more archetypes for what a successful founder looks like.

The idea that there is one archetype for what a successful fintech founder looks like is fucking stupid. Take age as an example. Mark Zuckerberg (busy inventing the metaverse that none of us want) has said that “young people are just smarter”. Paul Graham, a co-founder of YC, has said that investors usually treat founders over the age of 32 with skepticism. And yet, research suggests that the most successful entrepreneurs are middle-aged and that prior relevant work experience is actually a strong predictor of future entrepreneurial success. No shit.

Investors: Invest your time and money in broadening your network.

Build relationships with female investors and investors of color. Collaborate with them on deals. Watch them conduct due diligence. Establish pipelines to rural and urban schools that you don’t have any connections with today. Explore new problem spaces within fintech, even if you are not planning to invest in them immediately.

Founders: Don’t blame yourself.

Successfully building a venture-backed startup is incredibly difficult, under the best circumstances. The current macro environment is extremely challenging, and founders of color and female founders have a much steeper hill to climb, regardless of the macro environment.

Multiple founders who I spoke with emphasized the importance of not letting failure, particularly failure to raise capital, negatively impact mental health.