07 October 2022 | FinTech

BNPL’s Biggest Problem …

By Alex Johnson

… is that it’s unpredictable.

Now, let’s pause here and cup a hand around our ear and listen for the indignant objections of all those who work for or invest in BNPL providers … it should just be a sec …

Unpredictable?!? WTF? Our product is vastly more predictable and transparent and safe to use than credit cards. That’s the whole point!

I know! I hear you, BNPL fans! I hear you. I completely understand where you are coming from.

But give me a chance to explain my perspective!

The Current State of BNPL in the U.S.

I want to start with a quick level set on where we are right now with BNPL.

To do that, I’ll be drawing from a recent research report that the CFPB published on the U.S. BNPL market. The report, which focuses exclusively on the pay-in-4 variety of BNPL (which is the most novel and popular form of BNPL in the market today), is the most comprehensive analysis ever done on the U.S. BNPL market. It contains a wealth of interesting insights. I also found this report extremely fair. It points out the good, the bad, and the weird of BNPL and it was assembled with heavy input from the BNPL industry, especially five of the largest BNPL providers in the U.S. – Affirm, Afterpay, Klarna, PayPal, and Zip/Quadpay – which were all required to answer a “detailed set of qualitative and quantitative questions” posed to them by the CFPB.

So, what’s the current state of BNPL in the U.S.?

There are three things you need to know:

#1: BNPL is big and growing bigger.

As the CFPB notes, the last three years have seen a boom in pay-in-4 BNPL:

The BNPL industry is in the midst of rapid growth. From 2019 to 2021, the number of BNPL loans originated in the U.S. by the five lenders surveyed grew by 970 percent, from 16.8 to 180 million, while the dollar volume of those originations (commonly referred to as Gross Merchandise Volume, or GMV) grew by 1,092 percent, from $2 billion to $24.2 billion.

This growth has been driven by a wide and widening credit box:

73 percent of applicants were approved for credit in 2021, up from 69 percent in 2020.

And diversification of the merchants that BNPL providers partner with:

The industry mix of BNPL usage is diversifying. Apparel and beauty merchants, who had combined to account for 80.1 percent of originations in 2019, only accounted for 58.6 percent in 2021.

Which, in addition to bringing more consumers into the BNPL market, also likely contributed to larger average order values:

The average individual order value (i.e., average purchase amount financed by a BNPL loan) in 2021 was $135, up from $121 in 2020.

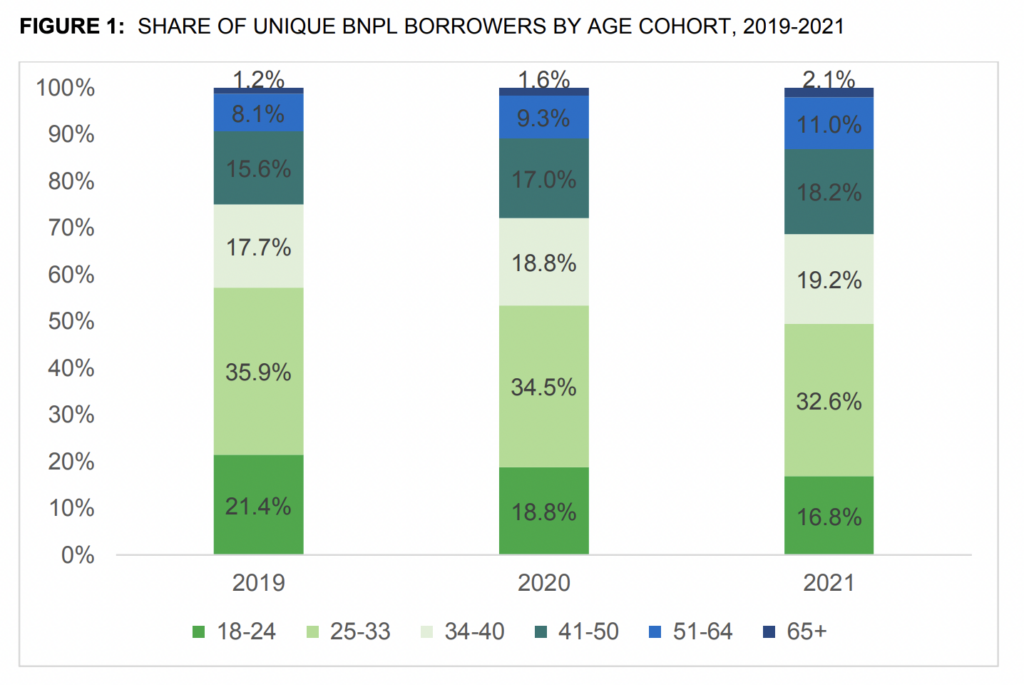

And, of course, BNPL remains incredibly popular with Gen Z and younger Millennials, although interestingly we have seen older Millennials, Gen X, and even Baby Boomers pick up share in the last few years:

#2: Performance is starting to deteriorate.

However, with popularity comes problems.

As the CFPB notes, unit margins for the five largest BNPL providers in the U.S. are compressing:

Unit margins (unit revenues less unit expenses) were 1.01 percent of GMV in 2021, down from 1.27 percent in 2020. This reduction in margins stemmed from two sources: a decrease in revenues from merchant discount fees (fees merchants paid to BNPL lenders), and an increase in credit losses. An additional pressure point on lenders’ unit margins arose in the first half of 2022: increasing funding costs, stemming from a combination of idiosyncratic and macroeconomic conditions.

Digging in a bit, the CFPB argues that the decrease in revenue from merchant discount fees is largely due to competition:

The main cause of this decline was increased competition: the entrance of new players (two of the five lenders surveyed, among other entrants, began originating BNPL loans in the U.S. within the last two years), along with further entrenchment of existing players. At the same time, lenders improved and streamlined their merchant onboarding processes, which reduced merchants’ switching costs and further contributed to competition for merchant partnerships. “The price has dropped due to competition,” one BNPL executive acknowledged in January 2022.

And increased credit losses are largely the result of the same macroeconomic forces that have been impacting the performance of other consumer lending product categories in recent months:

This increase in BNPL losses has mirrored credit trends in similar lending sectors: personal loan delinquencies were up 11 percent from Q4 ’20 to Q4 ’21; “new delinquencies” of unsecured fintech personal loans climbed throughout the end of Q4 ’21 and into Q1 ’22 to the highest levels since at least 2016; and bank credit card defaults increased each month from December ’21 through April ’22.

Although the bureau points out that these challenging macro conditions may hit BNPL a little harder:

In a reference point that may be especially relevant for BNPL given its youthful demographic skew, one study found that transitions into serious credit card delinquency rose for the 18—29 and 30—39 age demographics from Q3 ’21 to Q1 ’22 at the same time that they fell for the 40—49, 50—59, 60—69, and 70+ demographics.

And finally, while it’s a bit too soon to say exactly how rising interest rates will impact BNPL providers, the early indicators aren’t great:

One BNPL lender directly addressed the substantial impact of interest rate increases on its unit margins during a 2022 earnings call: “[W]e estimate the impact to Revenue less transaction costs as a percentage of GMV to be approximately 40 bps for every 100 basis points of rate movement beyond the current forward curve.” The public filings from another BNPL lender corroborated this sentiment. Its funding costs as a percent of originations increased by 33 percent (0.30 percent to 0.40 percent) from Q2 ’21 to Q2 ’22, reflecting the increase in interest rates that occurred in the latter period.

#3: BNPL providers are shifting their strategies.

In response to these challenging unit economics, the CFPB observes that the big BNPL providers are shifting their strategies:

BNPL lenders have adjusted their business models and strategies in a variety of ways, including tightening underwriting, increasing their reliance on consumer fees (namely, late fees and other fees), and shifting toward the app-driven “lead generation” acquisition model.

Let’s unpack each of these, just a bit more, starting with tightened underwriting:

In June 2022, one BNPL lender confirmed that it was tightening underwriting as part of a “real focus on sustainable growth, strong unit economics and, critically, accelerating our pathway to profitability,” while another lender confirmed that it made similar underwriting adjustments “to reflect this evolving market context.”

In its FY ’22 annual report (published in August 2022, for the fiscal year that ran from July 2021 through June 2022), one of the lenders quoted in the prior paragraph provided some additional context to its policies changes: “[BNPL lender] has tightened its decisioning rules and cut off scores, enhanced credit limit management and optimised its approach to repayments and collections.”

On its August 2022 earnings call, another BNPL lender detailed underwriting adjustments outside of the scope of reducing approval rates, including “tightening in durations, asking for a more down payment, in some cases, asking for incremental income information.”

And increased reliance on fee revenue, which the bureau doesn’t make a particularly strong case for IMHO:

In aggregate, the five lenders surveyed have increased their share of revenue coming from consumer fees, from 11.7 percent in 2020 to 13.4 percent in 2021. However, the shift was not consistent across the lenders: three experienced an increase, one experienced a decrease, while another did not charge consumer fees in either year.

The three lenders with increased consumer fee revenues did not raise the size of each late fee, but the number of consumers who paid late fees increased. For these lenders, the borrower-level late fee rate increased anywhere from 3 to 10 percent between 2020 and 2021.

Another means to increase consumer fee revenues without increasing nominal fee amounts is to collect a higher share of assessed fees, a strategy employed by one or more of the five lenders surveyed between 2020 and 2021.

(So … three of the big five BNPL providers earned more money from fees because more consumers missed payments [as we already discussed], but the three providers that saw increased fee revenue didn’t raise the cost of their late fees and only one of the big five ramped up its collection efforts on unpaid late fees. Uhm, OK.)

And finally, the one that the CFPB seems most concerned about – the increased focus on an app-driven acquisition model:

While BNPL lenders acquire the majority of their users via the merchant partner model … many are rapidly shifting toward a model of direct consumer engagement. In this app-driven acquisition model, consumers preemptively complete the credit application process with the BNPL lender on its proprietary app. Once approved, consumers receive access to a virtual shopping mall of merchants to patronize, along with a purported credit amount provided by the lender.

The underlying technology powering the app-driven acquisition model is a single-use, bank-issued virtual card that an approved applicant uses to complete a BNPL loan. The virtual card technology provides BNPL lenders with two important benefits. First, it allows nearly any merchant who engages in ecommerce to accept BNPL—even if the merchant has not signed a specific contract with the BNPL lender. This group of merchants are referred to as “nonpartnered merchants,” as they facilitate BNPL loans without a specific integrated partnership with the lender who originated the BNPL loan. Second, it allows lenders to share in a portion of the interchange fees that are collected from the virtual card transaction.

More generally, the app-driven model strengthens the consumer’s relationship with the BNPL lender by driving the consumer to begin (and often end) their purchase journey within the lender’s self-contained app ecosystem.

If you’ve spent any time inside a BNPL app recently, you’ll know exactly what the bureau is talking about when it refers to a “virtual shopping mall”. Here’s what Affirm looks like:

Is BNPL Good or Bad for Consumers?

This is the question that sits at the heart of the CFPB’s report.

The CFPB has a number of concerns about BNPL, which it groups into the following three categories:

- Discreet Consumer Harms – These are concerns about specific deficiencies in BNPL products and experiences that the bureau sees as harmful to consumers. Stuff like unclear disclosures and challenges resolving disputes.

- Data Harvesting – This is a broader concern about the ways in which BNPL providers are using (or could start using) the data they have gathered on consumers. This is a very common concern in the Chopra era of the CFPB.

- Overextension – This is the concern that BNPL is encouraging and facilitating consumers to get into unsustainable levels of debt.

I think these concerns are generally fair, but I don’t find this framing to be particularly useful in diagnosing the larger problems with BNPL. Too many trees getting in the way of the forest.

As I stated at the beginning of this essay, I think the biggest problem with BNPL is that it’s unpredictable. And I think that the reason this can be a bit hard to grok is that BNPL on a micro level – the individual transactions enabled for consumers – looks and acts very differently than BNPL on a macro level.

BNPL … On a Micro Level

On a micro level, it’s difficult to argue that credit cards are a more consumer-friendly product than BNPL is.

Sure, for the segment of consumers that never revolves a balance and always calls up their issuer and convinces them to waive the annual fee for another year, credit cards can be a safe, low-cost, and lucrative tool for making payments.

However, for many Americans, credit cards are a source of constant temptation, anxiety, and guilt. According to the CFPB, Americans pay roughly $120 billion per year in credit card interest and fees. Much of that cost is difficult for consumers to understand as it results from the compounding interest on unpaid balances, which credit card issuers are incentivized to encourage (within reasonable limits). Indeed, credit cards are, often, designed to confuse consumers. Shit, I wrote an essay for Fintech Takes a while back basically arguing that credit cards are an elaborate experiment designed to torture human beings.

By contrast, BNPL looks (in many respects) like a dream come true for consumers.

BNPL loans typically don’t charge any interest. They don’t allow for balances to revolve. Some of them don’t even charge late fees. There is no incentive, on the part of the BNPL provider, to encourage or deceive customers into not paying their bills fully. The total balance of any one BNPL loan is usually small, which helps limit the amount of trouble consumers can get in and virtually guarantees that, if they do get into trouble, they likely won’t be harassed by a collection agent calling them on the phone every day (because it isn’t worth the money to manually collect on).

Put simply, individual BNPL loans are transparent, safe, and predictable … in ways that credit cards just aren’t.

BNPL … On a Macro Level

The problems with BNPL only become apparent when you take a step back and look at it, not as a product, but as a complex system.

A well-accepted tenet of systems theory is that systems can have ‘emergent properties’ – characteristics that are not apparent or explainable when you study any one component within a system, but that arise out of the complex interactions between multiple components within a system (e.g. consciousness is an emergent property of the complex chemical communications infrastructure that is the human brain).

As BNPL has grown and established itself as a major sector within the payments and lending industries, I have observed the appearance of a number of complex and unpredictable emergent properties, which I believe represent the greatest problems (and opportunities) within BNPL today.

Let’s quickly walk through them.

#1: The Dispute Problem

The growing usage of BNPL (particularly in e-commerce) raises an interesting question – what can consumers do if they have a problem with a specific transaction?

In the world of credit cards, the answer is simple and well understood – file a chargeback. Consumers who have a valid complaint relating to an unauthorized transaction or a billing error or a problem with a merchant have the legal right (under the Fair Credit Billing Act) to file an official complaint with their credit card issuer, which the issuer is then obligated to investigate and resolve, without the customer being financially responsible for the transaction in question during the investigation period. This is a powerful and increasingly used tool in the hands of consumers.

However, the Fair Credit Billing Act doesn’t apply to installment loans. So the process for consumers to seek redress when they have a problem with a specific BNPL transaction is … more complicated:

The return process may be complicated when the merchant declines to authorize a refund for a disputed item. In these cases, a borrower may contact the BNPL lender to file a dispute, either via the lender’s app or by contacting customer support. The BNPL lender then generally begins an investigation and contacts both the borrower and merchant. Once the investigation is concluded, the lender assigns responsibility to one party and may issue a refund or credit. However, with the short-term, six-week nature of BNPL loans, a successful merchant dispute may not be resolved during the loan term. In these instances, the borrower may be required to make additional payments under the loan contract until the investigation is concluded.

In the event of a non-partnered loan facilitated by a virtual card, dispute resolution is complicated by the involvement of issuer processors that are responsible for generating the single-use cards. Disputes initiated by the borrower through the BNPL lender are mediated through the issuer processor before reaching the merchant. Likewise, a return or refund initiated by the merchant must go through the issuer processor before reaching the BNPL lender. Since the merchant is unable to distinguish a BNPL single-use card from other card transactions, the merchant may be unaware of the BNPL lender’s role, creating potential communication lapses and leaving borrowers responsible for ongoing payments during these lapses. As one borrower who experienced issues with a virtual card transaction noted in a CFPB complaint narrative, “I called [merchant] and they had no idea who [BNPL lender] was… [BNPL lender] and [merchant] are pointing fingers at each other and I am left holding the bag.

#2: The Credit Line Problem

For all their many faults, one of the nice things about credit cards is that consumers always know exactly how much credit (i.e. available purchasing power) they have at any given time (credit limit minus current balance). This is enormously helpful for consumers, particularly those living paycheck to paycheck.

Because BNPL was originally conceived of as a point-in-time transactional tool, the concept of a credit line for a specific customer wasn’t really a thing:

Historically, consumers interacting with BNPL lenders via the merchant partner acquisition model did not see their credit assignment amount separate from the present transaction. Since the original iterations of BNPL were executed at checkout, the credit assignment process was often interwoven with the ultimate approval/decline decision for the specific purchase in question.

However, as BNPL providers shifted from a merchant partner acquisition model to an app-driven acquisition model, the concept of an ongoing credit line became more relevant:

The app-driven acquisition model has made the amount of available credit for which a consumer is qualified much more explicit. Upon logging into the app, users are often guided to immediately apply for credit (before they have selected a purchase). Approved users are then typically presented with a purported available credit amount, sometimes referred to as “purchase power,” “pre-approved to spend,” “estimated spending power,” or “prequalified to spend.” The approved amount is usually considered a placeholder until the user actually attempts to take a BNPL loan, at which point they are re-underwritten.

But because BNPL providers usually re-underwrite customers each time they make a transaction, it can be unclear exactly how much credit is actually available to consumers:

Through CFPB complaints, some consumers reported that BNPL lenders lack transparency regarding credit assignment … consumers have noted that their available credit, as displayed, may not reflect the user’s actual purchasing power at a given lender. As one user noted, “consistently [BNPL lender] tells its users that they have about $1300.00 in credit but only ever allows it to spend just under $300.00 over time no matter whether one has excellent payment history, pays early, has excellent credit rating… the policy is not clear.” These declines may inhibit the consumer’s ability to effectively plan for certain purchases and affect their relationships with lenders and merchants.

#3: The Cash Flow Problem

It is increasingly common for consumers to take out multiple BNPL loans at the same time:

In Q4 ’21, 15.5 percent of unique borrowers took out five or more BNPL loans, a 144 percent increase from Q1 ’19 and a 20 percent increase from Q4 ’20. On a normalized basis, the growth figures are even more pronounced for the share of borrowers who took out ten or more BNPL loans, with a 251 percent increase from Q1 ’19 to Q4 ’21 (1.1 to 4.0 percent) and a 34 percent increase from Q4 ’20 to Q4 ’21 (3.0 to 4.0 percent).

Because consumers often take these loans out from multiple BNPL providers (either through the merchant partners that they shop with or directly from the BNPL apps), it’s unlikely that any one BNPL provider will have an accurate view of the total number of concurrent loans that these consumers have. Additionally, because most of the big BNPL providers don’t currently furnish data to the credit bureaus or share consumer-permissioned data through APIs to the data aggregators, there is no mechanism in place today for any stakeholder (consumers, the BNPL providers, other lenders) to assemble the full picture of a consumer’s BNPL debt obligations or to understand the resulting impact on that consumer’s cashflow.

This has several important implications.

For consumers, it means that it is very easy to lose track of their payments. This is especially concerning given that most big BNPL providers require their customers to set up autopay for their loans (usually with a debit card or credit card), which can limit consumers’ flexibility when managing cashflow shortages:

forced autopay may have the effect of depriving those borrowers of a degree of agency. A borrower facing multiple concurrent debts and bills may prefer to prioritize other obligations over their BNPL loan, and policies that limit that ability can be harmful to the borrower’s financial well-being. Likewise, not allowing borrowers to easily remove their payment method could inadvertently lead to overdraft.

For BNPL providers and other lenders, it means that they lack the ability to assess the ability to pay for customers and prospects who are heavy and sustained users of BNPL.

#4: The Credit Scoring Problem

Most of the big BNPL providers use traditional credit data and scores from the credit bureaus to help them underwrite consumers for their loans. Almost none of the big BNPL providers currently furnish data back to the credit bureaus, which is probably for the best because the credit bureaus have absolutely no idea how to incorporate BNPL repayment data into their credit files:

Where do you put BNPL pay-in-4? It’s an installment loan, but it also looks nothing like a traditional installment loan. 25% of the principal is repaid immediately. And there is no interest. And the loan amounts are tiny compared to even the smallest traditional unsecured installment loan. It also looks a little like a revolving line of credit – the BNPL providers usually underwrite each customer for a maximum loan amount that each individual BNPL transaction then eats into, kind of like a credit card – but it’s also clearly not a credit card.

Maybe you just throw up your hands and create a separate specialty bureau for BNPL?

There aren’t any obviously correct answers, and the way we know that is that the credit bureaus, who have been studying this problem extensively for the last few years, have opted for different answers.

BNPL has reached a scale where it has become untenable for repayment data not to be reported to the credit bureaus, which is why the bureaus and the big BNPL providers are all working on getting the data added in. However, no one knows how this new data (and how it is incorporated by the bureaus into their credit files) will impact consumers’ credit scores or the efficacy of lenders’ underwriting models, which isn’t ideal.

#5: The Business Model Problem

The most nebulous, but also perhaps most important problem facing the BNPL space is how will BNPL products (which tens of millions of consumers rely on) change in response to a rapidly changing macroeconomic environment?

Given rising charge-off rates and an increasing cost of capital (which hits BNPL providers harder because they lack bank charters and the cheap deposits that come with them), might we see a pullback in the availability of credit offered by BNPL providers? The CFPB argues that we already are:

From Q3 ‘21 to Q4 ’21, the credit approval rates for each of the five lenders surveyed declined; in aggregate, their approval rate dropped from 75 to 72 percent. Part of this effect was seasonal; approvals often decline in the fourth quarter, as credit-seeking holiday shoppers make up a disproportionate share of the applicant pool. But another part of it was the beginning of a trend that has accelerated since the start of 2022 to tighten underwriting standards in order to reverse worsening credit losses.

Making BNPL More Predictable

The good news for the BNPL industry is that most of these problems are fixable. After all, in financial services, we have a lot of experience finding ways to tame (or at least tamp down) the emergent properties arising from complex systems.

Here are a few thoughts on how U.S. BNPL providers might do that:

- Invest in better dispute resolution. Just because they aren’t yet subject to the Fair Credit Billing Act doesn’t mean BNPL providers shouldn’t invest in more robust and customer-friendly processes for handling merchant disputes. In fact, it seems like that might already be happening – the dollar refund rate on disputes for the big five BNPL providers increased from 45% in 2019 to 60% in 2021.

- Take bigger credit risks for your best customers. I understand why BNPL providers like to re-underwrite every transaction for every customer – it’s an effective way to mitigate risk and keep down loss rates. However, it also makes it difficult for customers to trust that they will have the available credit they need. Taking more risks and approving firmer credit limits for the best customers will pay dividends.

- Prioritize consumer-permissioned data sharing. It’s absurd that PFM apps can’t help consumers track and manage their BNPL loans because the big BNPL providers haven’t prioritized the creation of API integrations with the data aggregators. I know no one wants to make it easy to share proprietary data, but the faster the BNPL providers get over themselves on this issue, the better off everyone will be.

- Build credit scoring tools for other lenders. Until the bureaus modernize the way that they capture and organize data and FICO speeds up its process for updating its scoring model, BNPL is going to continue to be a headache for the credit scoring industry and for all the lenders that depend on it. In the meantime, I wonder if the big BNPL providers should build their own proprietary credit scoring modules to assist other lenders with interpreting their customers’ performance data?

- Diversify the business model. Obviously, this one is already well underway, with BNPL providers shifting to an app-driven acquisition model and spinning up new revenue drivers like affiliate marketing. I’d like to see even more being done on this front, including the incorporation of bank charters into these lending models in order to reduce funding costs and risk (Afterpay may do this sooner rather than later given that Square has a bank charter now).