30 September 2022 | FinTech

The Fintech Factor

By Alex Johnson

Here’s my working theory for today’s essay:

The best thing about building fintech products 10-15 years ago was the complete and utter lack of fintech infrastructure available for founders to use.

Now, I know that the OG fintech founders out there may balk at this statement. I know what they went through to get those first fintech products off the ground. I know it left them with more gray hairs than they had when they started. I know they would have killed for some robust low-code tools and APIs back when they first started building.

I mean look at Simple. It took those guys three years, from when they first came up with the idea, to actually build and launch the product.

But that’s exactly my point.

It took them three years because no one had ever done anything like that before. Neobanks weren’t a thing. Banking-as-a-Service (BaaS) had existed for a while, in the same way that humans existed before homo sapiens, but certainly not in the form that we understand today. They had to build all of that from scratch. They had to negotiate their partnership with The Bancorp Bank without any precedent or roadmap to guide them.

And by the time they were ready to start telling consumers what they were up to (in November of 2011) and getting them signed up for their waitlist, they could feel confident that the product they were bringing to market was highly differentiated:

Look at that screenshot. In 2022, no one would care. No one would even notice. This would just be another generic neobank, swimming in a sea already crowded with neobanks.

But in 2011, this simple promise – that consumers could ditch their bank and go to a simpler and less punitive alternative – was so revolutionary that Simple signed up hundreds of thousands of consumers for its waitlist, without even really having to lift a finger.

In other words, 10-15 years ago, manufacturing fintech products was so difficult that anyone who managed to actually do it was virtually guaranteed to end up with a highly differentiated product that would practically sell itself.

It was the same story in the world of fintech infrastructure.

15 years ago, I worked for a fintech company based in Bozeman, MT called Zoot Enterprises. Unless you’re extremely well-versed in the early history of cloud-based credit decisioning, you probably haven’t heard of them, so you’ll just need to take my word for this – Zoot pioneered many of the fintech infrastructure categories that we take for granted today. And they did it all without the benefit of being able to build on top of or in collaboration with the modern infrastructure and tooling that we have today. For just one example, consider this – AWS didn’t exist at the time. So in order to build a SaaS-based credit decisioning and digital account opening product, Zoot first had to build its own distributed data centers and cloud computing environment … in Bozeman, MT. Here’s a screenshot of a white paper I wrote in 2009, making the case to banks for why Zoot’s investment in cloud computing and its belief in SaaS weren’t crazy:

Zoot’s products weren’t quick or easy to build, but you know what? They were easy to sell. They practically jumped off the shelves! If you were a financial services provider looking to do something really innovative in consumer lending in the 2000s, you basically had to work with Zoot. They were the only game in town. Which explains why, when I was working there, we were able to truthfully claim that we processed transactions for 7 of the 10 largest financial institutions in the U.S. That’s a claim that not many fintech infrastructure startups today can make.

I bring all of this up simply to illustrate how different building in fintech is today.

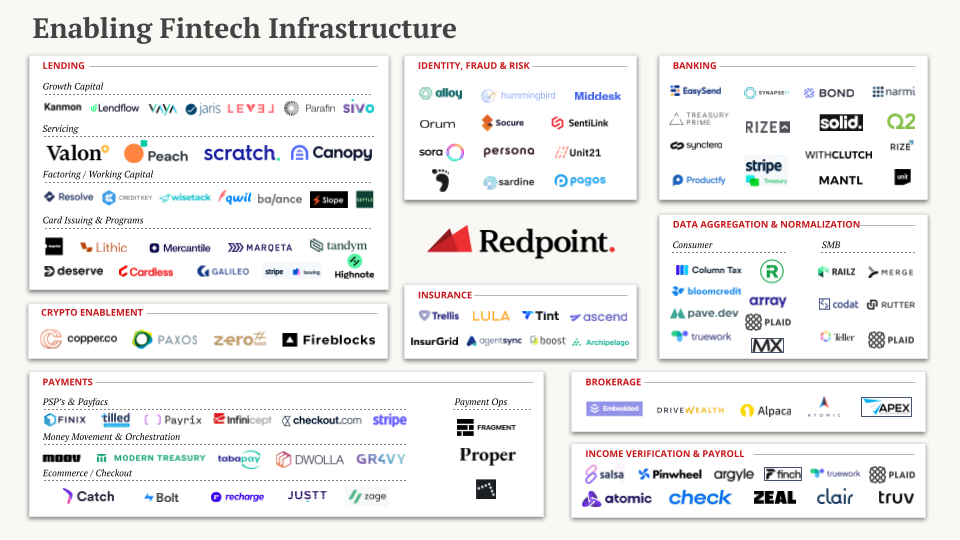

Today, fintech founders have a myriad of different options for quickly and easily building their products. This graphic from Redpoint Ventures provides a compelling and not-even-close-to-comprehensive view into what this smorgasbord looks like:

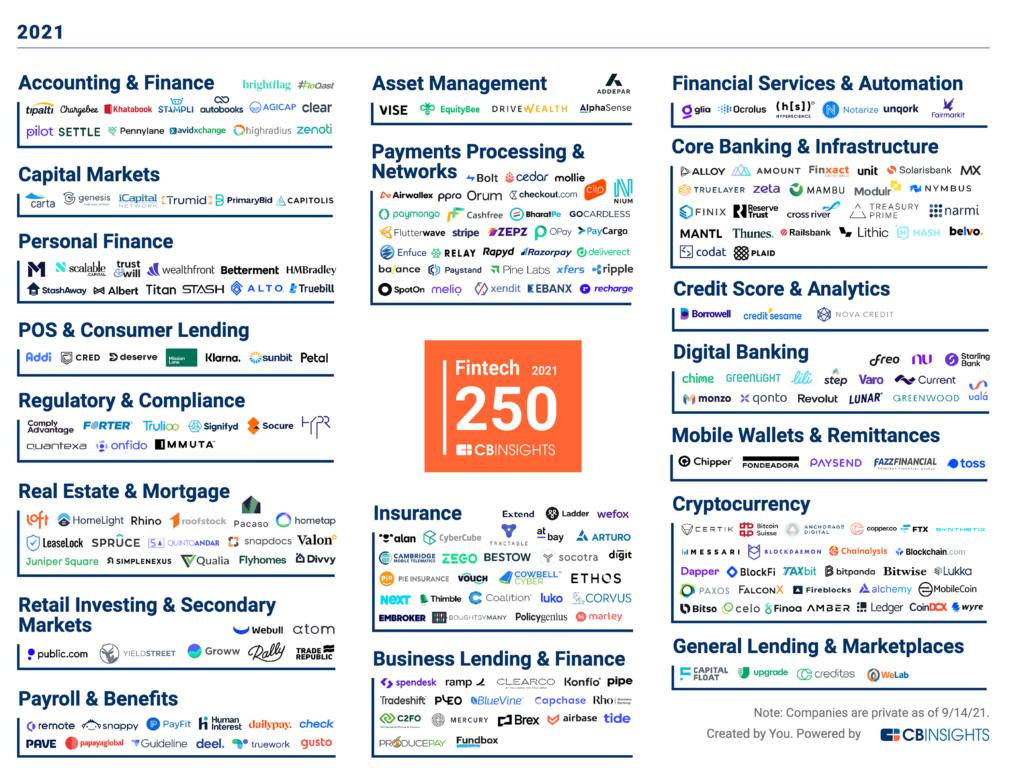

Tremendous. A builder’s dream. And yet, the easier it is to build a fintech product (be it infrastructure or a consumer-facing product), the more likely it is that we will see a plethora of such products emerge into the market … particularly when you combine these advanced tools for manufacturing with a flood of venture capital funding … which is exactly what we’ve had recently:

The result is a mountain of fintech products, with very little to differentiate them from a manufacturing point of view, all locked in a fierce battle for distribution.

Which brings us to a corollary of the theory I shared at the beginning of this essay:

The most important thing about building fintech products today is not assuming that the quickest, easiest, and least expensive path forward is the best path forward.

The Value of Doing Hard Things

I’ve been obsessing over this question for the last year or so – if anyone can now quickly and easily start a fintech company and build fintech products (thanks to all this infrastructure), how can any fintech company sustainably achieve competitive differentiation?

In order to answer this question and gather evidence for my theory that the best fintech companies are built slowly and by solving really hard problems, I created a podcast – The Fintech Factor.

In the podcast, I interviewed four executives from four very different fintech companies; companies that have kept stubbornly running into walls (where their peers have run around them) and have found, often to their surprise, that those collisions (and the eventual breakthroughs) were the source of much of their competitive differentiation.

I just published the fourth and final episode of the podcast this week, so I thought it would be a good time to summarize each of them – the challenge that the company had to overcome, the solution they landed on, and a unique insight that I gleaned from the conversation.

Episode #1: TripActions Liquid

In the inaugural episode, I interviewed Michael Sindicich, EVP and GM of TripActions Liquid.

Challenge

I’ve written a lot about the corporate spend management space, and for good reason – in less than four years, four of the leading fintech companies in the corporate spend management space raised more than $3.5 billion in venture funding. This is an intensely competitive space. And every company competing in it has a different angle, a different approach for how they are going to try to win – Brex is focused on venture-backed startups (much to the frustration of some small business owners), Ramp and Airbase are focused on software, Rho and Mercury are focused on banking, Rippling is focused on trying to provide everything.

When compared with these companies, TripActions certainly stands out. The company just got into the spend management space with its Liquid product a couple of years ago (February 2020) and the Liquid product suite is significantly less broad than its competitors.

So, how can TripActions win?

Solution: By solving 100% of the problem.

TripActions isn’t focused on solving all corporate spend management problems. It is laser-focused on solving just one – corporate travel spend management.

Now, that problem is still quite big (70% of expenses at a typical company relate, in some way, to travel), but the key to TripActions’ competitive differentiation is that it spent five years and hundreds of millions of dollars building a modern corporate travel booking and management platform before it ever even considered adding a corporate card or spend management capabilities.

TripActions’ core travel booking and management platform provides Liquid with the context that it needs to automate traditionally manual expense management processes. For example, if an employee swipes their corporate card in a grocery store, TripActions Liquid has the context to understand if that transaction should be automatically reimbursed, based on that employee’s travel schedule, the location of the grocery store, the specific items purchased at the store, and its understanding of how the company’s travel expense policies for that specific employee map to those items. And that understanding can drive automated workflows and efficient manual intervention (where needed).

Unique Insight

One of the things Michael said during our interview that really stuck with me was, “the card is the technology.”

He was commenting on the fact that, traditionally, corporate cards and expense management systems have been separate product categories. This might have made sense at one time, when financial products were more physical than digital. However, that paradigm has flipped. Financial products, including and especially payment cards, are now software primitives.

Michael’s point was that, as fun and exciting as fintech is, if you are trying to solve 100% of your target customer’s problem, it often makes more sense to start outside of fintech and only add in the fintech primitives when and how you need to.

Episode #2: NeuroID

In the second episode, I spoke with Jack Alton, CEO of NeuroID.

Challenge

NeuroID is focused on helping banks and fintech companies address the growing digital identity crisis and prevent fraud.

The challenge for NeuroID (or any vendor operating in this space) is that earning a place in a bank’s ‘fraud prevention stack’ is really freaking hard. You are selling a better mousetrap (a new data source or analytic model or what have you), and in order to get your product added into the waterfall of different fraud detection products that the bank is already using, you need to demonstrate that A.) it provides a significant and differentiated lift to the bank’s fraud catch rate, B.) the additional friction it introduces into the user experience is worth it, and C.) that the value of your product (both in improving fraud catch rate and not introducing too much friction for legitimate customers) is worth the cost (for both the initial set up and the ongoing transactions).

If you haven’t been through this sales process before, trust me – it’s a nightmare. And it never stops because once you’ve sold your way in, you have to keep your place in the stack, while fraudsters evolve their tactics and dozens of new vendors (with new shiny mousetraps) try to replace you.

Most vendors in the fraud prevention space eventually pivot from trying to sell point solutions to trying to sell an orchestration platform. Put simply, they pivot from trying to earn a place in the waterfall of different products used to detect fraud to providing the system that facilitates that waterfall decisioning process. You can see the appeal of this – orchestration is a much stickier service to provide and it doesn’t require the same level of ongoing R&D as providing a point solution requires.

The trouble is, every fraud prevention vendor knows and (eventually) follows this exact playbook. So, how do you differentiate yourself?

Solution: By understanding the unique value of your solution.

NeuroID provides a behavioral analytics solution that evaluates the intent of anonymous users interacting with a bank’s digital onboarding journeys. The insights generated by this solution are significantly different from the vast majority of fact-based data that banks have historically used to detect and stop fraud.

Now, different is good because it helps NeuroID stand out from the crowd. But it’s also bad because the full value of NeuroID’s product is nuanced and difficult to compare, apples-to-apples, with more traditional fraud data products.

NeuroID spent quite a bit of time in the trenches, selling its product into the ‘fraud prevention stacks’ of many banks and fintech companies. And I would have bet that a pivot to becoming an orchestration platform was going to be the company’s next step.

I would have been wrong.

Instead of pivoting to compete as yet another fraud data and decisioning platform, NeuroID realized that its behavioral analytics capability could be embedded into all of the existing platforms and used, at the very top of the waterful, to give banks and fintech companies insights into the intent of every user starting their digital onboarding journey and to steer those journeys based on the risk each user poses.

Unique Insight

As Jack told me on the podcast, “the industry has enough platforms. What it needs is more instrumentation. We want to instrument existing platforms and make them better.”

Put simply, NeuroID chose a distribution strategy based on what its product is uniquely good at, not based on what everyone else in its market had previously done.

Episode #3: Nova Credit

In the third episode, I interviewed Misha Esipov, CEO of Nova Credit.

Challenge

There are 40-60 million adults in the U.S. that can’t be approved for credit using traditional credit evaluation tools like the FICO Score. This population is referred to as Credit Invisibles.

This is a very popular area of focus and investment in fintech. Lots of great companies and products have been built around the promise of helping consumers establish and build good credit histories. The problem is that a lot of these products involve a certain amount of trickiness. Now, I’m not always opposed to a little fintech trickiness, employed in the service of disrupting incumbents. However, in the case of credit building, I don’t love it because it can often have a deleterious long-term effect on the overall lending ecosystem and that’s bad for everyone (I wrote about this a lot more here). It’s also bad for the fintech companies themselves because, long-term, it puts them at risk if/when the incumbents that are being adversely impacted decide to adjust their systems to account for these tricks.

So, the question is this – how do you build a sustainably differentiated solution to the problem of credit invisibility?

Solution: By not taking shortcuts.

Nova Credit is a fully regulated consumer reporting agency (CRA), as defined and governed by the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

It has built out the infrastructure to facilitate consumer-permissioned data sharing across countries (allowing immigrants to take their credit histories with them when they move) and across bank product types (allowing consumers to pull cashflow data from their deposit accounts in order to supplement their traditional credit data).

Nova has sold these services to large banks (like American Express) and non-banks (like Verizon), which, again you’ll have to trust me if you’ve never experienced it, isn’t quick, easy, or fun.

Put simply, Nova Credit hasn’t taken any shortcuts.

Unique Insight

This quote from Misha really jumped out to me, “you have to be problem-first in building a business. You need to identify an acute pain and dissect it from all 360 degrees. You have to be able to look at it from every possible angle and really understand it from a first principles perspective.”

Deeply understanding the credit reporting system in the U.S. is hard. Deeply understanding the credit reporting systems of almost every country on Earth is infinitely harder. And yet, if you want to build a borderless credit-granting infrastructure and sell it to large banks and non-bank companies, that’s exactly where you need to start.

Episode #4: MX

In the fourth and final episode, I interviewed the newly-appointed CEO of MX, Jim Magats.

Challenge

We’ve made a tremendous amount of progress in the U.S., over the last two decades, in building the infrastructure to enable consumers to share their financial data with whatever financial services providers they choose. And we’ve done it without a regulatory mandate (although some rulemaking is coming, likely in the Spring of next year, thanks to Dodd-Frank 1033).

That said, the rapid progress that we have realized has definitely ruffled a few feathers (to put it very mildly). Aggregators’ use of screen scraping has justifiably angered banks. Consumers’ increasing use of aggregators to access and power competitive fintech products and services has unjustifiably (but understandably) angered banks as well.

The success of the next phase of open finance in the U.S. will hinge on a greater level of collaboration and trust between all stakeholders in the ecosystem, and my question is how will that collaboration and trust be built?

Solution: By always picking the side of the customer.

The eternal challenge in operating a multi-sided network (and that’s what open finance is, a multi-sided network) is keeping all of the different stakeholders happy. It’s not easy. There are always disputes that need to be resolved, and those resolutions aren’t always going to be perfectly satisfying to each stakeholder.

The key is to adhere, in all cases, to an overarching principle – a North Star – in making these decisions. So that, even if they don’t like a specific decision, any aggrieved party will a least understand how and why the decision was made. They will, in other words, come to trust the process.

Open finance in the U.S. has, so far, revolved around the idea that, at the end of the day, it’s the customer’s data and everyone should do what’s right for the customer. That is, and should continue to be, the industry’s North Star.

Unique Insight

I immediately wrote this quote from Jim down in my notebook, it was that good – “don’t ship your strategic chessboard.”

In our conversation, Jim continually advocated for the idea that in any internal company debate about strategy, the side of customer value should always win. Always. This is a philosophy that stretches back to his days at PayPal (where he oversaw the company’s transition to a customer choice payment strategy), and it resonated with me when he cautioned against letting corporate strategy and business model priorities (your strategic chessboard) get in the way of doing what you know, instinctively, is right for your customers.

This Was Just a Preview

These summaries don’t do justice to the full podcast episodes. Not even close. Michael, Jack, Misha, and Jim shared a ton of great insights that fintech founders and operators can gain a lot of value from, so make sure to listen to all four episodes!